News

How do our names serve as a blessing, a burden, or a prophecy? In a world where identity is constantly in flux, how do they root us? And where can they take us?

These are the questions of nominative determinism, which draws on Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity, the idea that a person’s name can shape their choices, career, personality, and even forecast their destiny.

The mother tongue of both my parents is Arabic. In this language of 12.3 million words—one that has named the stars, shaped philosophy, and given text to number—how do we interpret the ‘me’ word, our name? Is a name a word at all? Or is it an extension of worth, a consecration? After all, what is named is recognised, and the nameless fades into obscurity. We do not call for what has no name. To name something is to give it context within the fluid expanse of our reality.

The study of names, or Onomastics, has long fascinated linguists, but neurobiology is also uncovering their deeper impact. Research shows that not only does hearing your own name trigger a distinct neural response (unlike electrical impulses for other words and names), but it also activates the brain regions tied to personality traits, like impulsivity and decisiveness. On an fMRI scan, the middle frontal cortex, superior temporal cortex, and cuneus are lighting up with activation. What this actually means is our brains are codifying names as salient anchors of identity. This reinforcement of self carries even greater weight in the context of migration, adaptation, and the quiet negotiations of identity in unfamiliar cultural landscapes.

It is unsurprising then, that the erasure of names is a psychological artillery of colonial violence. The Turkish state has long regulated naming to enforce a singular national identity, banning Kurdish names under laws requiring conformity to “national culture”, claiming that this is a moral fight against actions that hinder the reification of the Turkish state as a ‘unified’ entity. In 2002, seven parents in Dicle, Diyarbakır, were prosecuted for giving their children Kurdish names, accused of using militant code names. As Kurdish identity became more politicised, naming became an act of resistance, with activists using it to counter state-imposed ‘Turkification’ through the deliberate revival and promotion of indigenous Kurdish names. Beyond political targeting, such repressive assimilation policies are also an attack on the personal concept of self.

This isn’t new. In the late 19th century, U.S. boarding schools forced Native children to abandon their Indigenous names and languages, replacing them with American names and English-only policies. Stripped of their heritage, these children became symbols of forced assimilation, their identities overwritten by a colonial narrative from as young as seven years old. If names hold no power, why would tyrants fight so hard to erase them?

“I am from there. I am from here.

I am not there and I am not here.

I have two names, which meet and part,

and I have two languages.

I forget which of them I dream in.”

― Mahmoud Darwish

Living away from home is hearing your name in a language that does not recognise its roots–where its syllables are bent, and sometimes, its meaning is lost. You notice the tension between the weight of our names and their gradual dilution—whether by circumstance or your own volition. Mohammed becomes Moe, Zahra becomes Zee. In more extreme cases, Zulfiqar, the esteemed sword of Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, shortens to Zach. If names shape us, what does it mean to disown, distort, or anglicise them? Is this simply adaptation, a matter of practicality, or does it reflect the hidden recalibration of identity that migration so often demands?

When we cross that event boundary from the outside world into the doors of our homes, our names break out of the shell we hid them in for the day and take the shape, form and sound of the ones we were given at birth. That very entrance is the border by which our names meet and part. The name your mother or father calls to you is not always the one you respond to at work; in that threshold between public and private, our names are both reunited with their origins and shaped by the echoes of those who speak them.

I never felt connected to my name, Yasmin. It just felt ordinary, delicate and decorative—vacant of any sense of adventure. A defining moment for me came fairly recently. I reflected on a childhood memory, being in a botanical garden with my mother in Damascus, aged eight. It was there I first encountered the jasmine fragrance. Warm, milky, lingering like a half-remembered dream. Since leaving Syria, I feel I’ve been chasing that elusive scent my whole life, but to futile efforts. A pursuit that feels bound to my own temperament–an axis tilted on nostalgia and longing.

It made me see Yasmin more as an emblem, representing the often obsessive relationship I tend to have with my memories and their sensorial placements, as opposed to a beautiful but empty word-flower. Just as we are not born with our names, maybe, our names are not born with their meaning; they are instead realised through the journey. The first day you are named is when you’re given a name. The second is when you discover why it’s yours.

For example, to some people, my mother’s name Taghreed means birdsong. For others, it means a caged bird that insists, still, on singing. Shaden to some, means a little fawn, and to others, it means a young gazelle mature enough to spring freely in a forest. It seems that some of our names affirm freedom, or in my mother’s case, the rehearsal of freedom.

Sentimental value aside, patronymic traditions across SWANA and much of the Eastern world mean names are meant to serve as functional vessels of data, designed to preserve lineage.

It begins with the Ism, or first name, which can be traditional, descriptive, or even foreign. The last name is traditionally a family name and can come from any of the following: a nasab, laqab or nisba. Laqab is an epithet honouring personal traits—al-Tawil (the tall) or al-Farooq (he who distinguishes truth from falsehood). The Nasab traces genealogy through paternal ancestry, forming chains like Ubayy ibn Abbas ibn Sahl ibn Sa’d (son of, grandson of, and great-grandson of). The Nisba signals origin, tribe, or profession—al-Baghdadi (from Baghdad) or al-Attari (the perfumer). My own, al-Rabiei, is of pre-Islamic tribal origin and is common among Iraqis, both at home and across the diaspora—with high prevalence in Norway, Sweden and Qatar. Finally, the Kunya, like Abu Karim (father of Karim), is an honorific tied to one’s firstborn. It signifies parenthood while also reflecting identity and social standing within the cultural fabric.

In reflecting on the patronymic convention and how names orient us in the world, past present and future, I thought about the name of the martyr, or the deceased loved one. Our names after all are not limited by mortality like we are and act as eternal badges for the ghosts we become.

I had always been drawn to the Islamic and political reflections of martyrdom and how they influence language, especially in moments of loss, where the name transcends the individual and becomes a symbol of sacrifice, memory, and resistance.

Each new headline coming out of Gaza over the last year and a half had destroyed me afresh. It felt that words were always too hollow for the depravity unleashed by US-backed Israel, and that verbal insufficiency grew with each new horrific report. I distinctly remember one headline stopping me in my tracks:

“The Ministry of Health has issued a statement on Oct. 15, stating that 47 families—over 500 civilians—were wiped from the civil registry.”

This moment brought into sharp focus the terrifying scale of loss, and the absoluteness of erasure. To mourn a name that has been wiped from the record is to mourn the deliberate unravelling of identity itself. Al-Jazeera’s report detailed how 393 members of the Al-Najjar family (meaning “carpenter”) were brutally killed, spanning at least three generations of individual relatives. The forced silence of a lineage that should have endured. It pulls into question how far a name, especially through patronymic convention, can serve as an archive–and the crime that takes place once that archive is wiped.

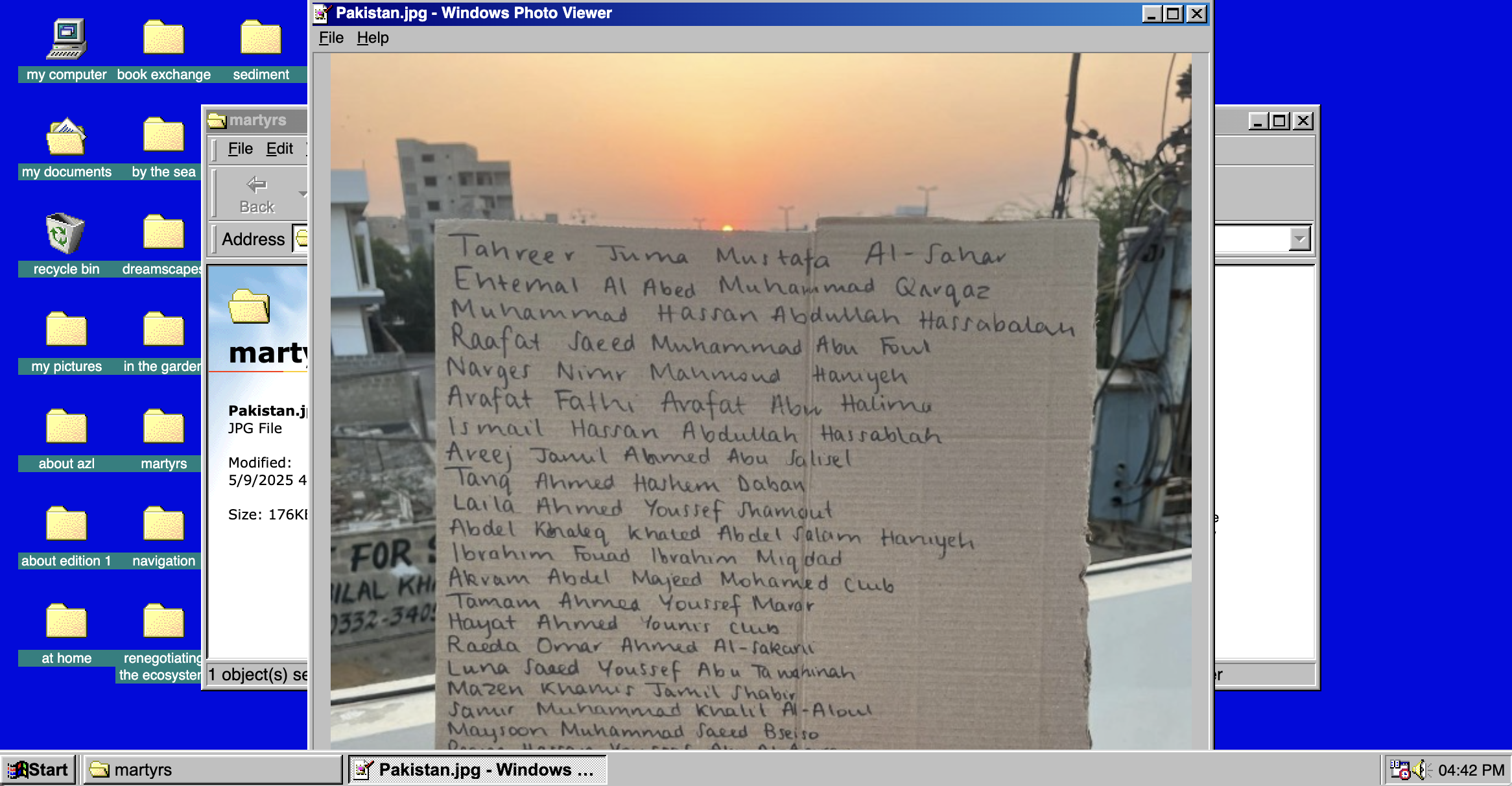

In response to this destruction, Azl Collective, an interdisciplinary digital platform for art, writing, and knowledge exchange, created the fundraiser workshop, A Ritual for Martyr Name Writing. Azl Collective was created by independent researchers and artists Shiza, Marah and Heidi.

“We began this project with various intentions, but mainly because there’s no way to hold funerals for everyone or appropriately honour the amount who have been killed in this genocide,” the team at Azl explain. “Moreover, they have consistently been reported as numbers, which continues their dehumanisation. In the words of Khalil from Gaza, ‘If I were martyred, I would not want to be a number. Tell my name, hear my story, and pray for me. I am not a number. I am a complete planet.’ We decided to write the names as an effort to sit with the names, write them out, and speak them out, as almost all individual names carry four generations of names within each one”.

As of 9 January, the Government Media Office in Gaza reported that 1,600 families had been completely erased from the civil registry–40 times as much as that first headline. The work of Azl indeed preserves their legacies; it resists the violence of forgetting, instead platforming the duty of remembrance.

This commitment to naming as an act of remembrance ties into a broader conversation about the region’s evolving cultural mosaic, where identities, traditions, and languages, like nature, are always in transition. This shift is even reflected in naming conventions. As cultural and social changes shape the quotidian, researchers are examining whether these linguistic traditions will endure or fade. A recent study of nearly 300 records in a Yemeni community highlights the rise of non-conventional names among women in tribal areas near Saudi Arabia, offering insight into shifting identities and traditions.

Many names were inspired by agriculture and weather, such as Nabatah (young plant) and Shatwah (winter). Others reflect geography, derived from cities and continents, like Barees (Paris) and Asia. Certain names commemorated significant events or social conditions at birth. These included Harbiah (born during the war), Wahdah (marking Yemeni unification), and Eidah (born on Eid). Others describe the circumstances of birth, such as Faj’ah (born suddenly) or Mubteyah (born after a prolonged pregnancy).

The prominence of weapon-related names reflects the cultural significance of weaponry in tribal customs as well as the history of armed conflict. Examples include Bazooka (and Qunbulah (grenade). The typology of female names in Saadah and surrounding regions clearly serves as a linguistic archive of Yemen’s traditions, industry and global interactions.

Similar patterns of influence have been observed in Jordan. Researchers tracing the evolution of naming practices from the 1970s to 2015 revealed how history, politics, and globalisation shape trends in names. In the 1970s, names like Jihad (struggle) and Nidal (struggle or fight) reflected resistance, inspired by events like the Battle of Karameh and the Naksa. By the 1980s and 1990s, urbanisation and technology favoured shorter, modern names like Rana (gaze or look) and Rami (archer), though political events such as the Iran-Iraq War still left their mark, with names like Saddam (the one who confronts) gaining prominence.

From 2000 onward, global influences—particularly from Western and Turkish media—saw a rise in names like Alma (“apple” in Turkish, “young woman” in Arabic) and Kenan (“promised land”), while moments of national trauma, such as the execution of Moath Al-Kasasbeh, spurred symbolic naming, with many boys named Moath (protected, defended) in his memory. As Arab identity shifts, so too do the names that carry its history, echoing the forces that shape who we become.

Beyond secondary onomastic studies, I figured it would be interesting to map names and engage in some research of my own. I had a wealth of case studies around me–friends from the region–and wanted to explore how people felt about their names, sparking the question of whether they had ever truly considered them.

Riwa from Lebanon tells me “I love this name, I do feel a connection to it. I’m interested in how names–these sounds that we respond to flavour our characters. Riwa means spring water, or to pour water and quench the thirst of the crops. My grandmother nicknames me “Riwayeh”, where “-yeh/-ya” is a suffix that makes something singular or little or cute, but changes the meaning in this case to “a narrated story”, I love this too, because I love telling and learning stories. My mom calls me “Riwati”, becoming “my Riwa”… I love that it has to do with water and harvest and feels cyclical in that sense, but also how in a literary context, it is about offering some form of nourishment.” This name is most prevalent in Tanzania, where 1 in 14,000 people have it.

Zeinab from Iraq tells me, “Growing up in the Netherlands, I didn’t really like my name when I was younger, I felt like it was very distinctive. Especially when I was young, and was just trying to blend in. However as I grew up, gained much more confidence in myself and had a deeper understanding of my heritage, I really started to love my name and started to appreciate the uniqueness. I feel driven to achieve great things because of the history of our people. I feel a name can be a powerful connector.” Zeinab is most prevalent in Kenya, where 1 in 22,000 people have this name.

Noor, whose name means earthly manifestation of primordial light, is from Palestine and Pakistan. She tells me, “Growing up in the UK, I resented the harsh British pronunciation of my name and felt like I couldn’t relate to the girls in my class. I’ve grown to love it as an adult, and I am working to connect the younger Noor to the light I was once running from”. Her name is most common in Pakistan, where 1 in 79 people have it.

Mohammed from Kurdistan and Palestine explains; “I know they reference this joke in the new series of Mo on Netflix, about shortening it to Mo. I do understand why some people do it. But all my life my parents ensured I de-platformed this fabricated myth of ‘West is Best’. I cannot live in either motherland, so the least I’ll do is wear this name with pride, and say it how it’s spoken back home. I’ll abbreviate it for no one.” This is the third most prevalent name in the world.

Names, evolutionarily, have served us well as a species with a compulsion for indexing things. That anthropic desire for categories means that names can act as quiet (sometimes, loud) markers of social, ideological, and cultural belonging.

It is almost ironic that in my family, our names that speak of blossoms and birdsong, etched with such poetic serenity, should belong to a lineage shaped by rupture, loss, and migration. Like so many Middle Eastern families, ours has carried its story across borders, arriving at unfamiliar shores with names that precede us, announcing our origins before we even speak. I’d like to think those themes of spring and nature foreshadow our capacity for renewal, which, across life and loss, we have so often needed.

A name is both deeply personal and entirely public, belonging to us but shaped by the way others call it, claim it, mispronounce it, or refuse to say it at all. Maybe our names are a reservoir of possibilities we are yet to imagine. Maybe they aren’t. After all, a name as a keeper of destiny feels a little burdensome. Maybe it’s just the one your mother landed on–“I knew when I held you”. Maybe it’s the sound that cuts through the noise, the one you turn towards if I call it in a crowded room. It’s the thing that, once you share with me, transforms us. The distance between us collapses and a thread is laid between self and other. We are no longer strangers.