News

Early last year, Rolling Stone unveiled a landmark tribute to Arabic pop music: a carefully curated list of the “50 Best Arabic Pop Songs of the 21st Century.” The article, written by prolific music journalist Danny Hajjar, remains the only deep dive of its kind, an ambitious attempt to trace the evolution of Arabic popular music and pinpoint its most defining moments over the past two decades. Naturally, music icons like Amr Diab, Nancy Ajram, Assala, Najwa Karam, Wael Kfoury, and Elissa claimed their rightful places on the list. Because really, who else would? Ask any Arab about Arabic pop, and their mind will likely drift to the golden age of Y2K hits, an era of melodramatic lyrics and delightfully low-budget green screen effects, now forever preserved in YouTube’s TV-ratio archives. It’s not just nostalgia, it’s the culmination of a generation’s musical memory.

Some more contemporary names made the list, such as Egyptian rapper Wegz who has taken the region and globe by storm since his 2017 debut. By 2022, he had cemented his status as the most-streamed Arab artist on Spotify. His success is emblematic of a larger 2010s movement. Over the past decade, Arabic rap and hip-hop have surged from the underground, sprouting through every seeming crack in every Arab country. Names like Shabjdeed, Al Nather, and Marwan Pablo, among handfuls of others, stand as pioneers. Hip-hop’s meteoric rise feels almost inevitable; it thrives as a vessel for raw expression, giving voice to political struggles and personal strife, speaking urgent and unfiltered. For example, in Egypt, the genre intertwines seamlessly with Mahraganat, the electronic auto-tuned soundtrack of the working class. Sociologically, the explanation is there.

All this points in one clear direction: while Arabic rap and hip-hop were having their moment, the pop music torch was extinguished, or simply not passed down. Whichever way you see it, it’s bad news (for me, and the average pop music enjoyer). So, where does that leave contemporary Arabic pop music, sans the rap? And it’s important to note here that pop does not necessarily denote popular music, but rather the typical characteristics of a pop song: repeated choruses and hooks, simple verse-chorus structures, easy to remember lyrics, danceable tempo, and so on.

The 2020s ushered in a new generation of Arabic pop artists, with TikTok at hand and a bedroom studio set up on overdrive. Long gone are the days when music execs and A&Rs scouted for artists IRL, all it takes today is a TikTok account and a scrolling session long enough to land on the next big thing. As music production has become more democratised and accessible, and the traditional legacy music industry gatekeepers much easier to bypass, a more diverse and experimental post-Y2K era Arabic electronic pop sound is emerging. And given all indicators, audiences are responding, and the industry is following suit.

“At the end of the day, the industry is listening to what people want… if I look at our roster at the beginning of [2024], we were so focused on rap. But now, our focus is on pop. And it’s because of the numbers,” explains Tarek El Mendelek, Talent Manager at independent Saudi record label MDLBEAST Records. “It started with the likes of Saint Levant and Elyanna in the diaspora, and certain pockets of rap [within the region] are certainly still doing very well, especially female rap, but the shift happened very naturally. It’s all tied to what people are listening to.”

This transformation could be explained by examining the well-oiled machine of Western pop, where image and marketing are just as crucial as the music. Industry jargon aside, independent pop artists understand a simple truth: you have to craft a persona that can’t be ignored. And look no further than the Egyptian TUL8TE as a case study. Shedding his lesser-known hip-hop roots, he reinvented himself with a 90s bossa-nova-inspired sound on Cocktail Ghena’y (2024), his breakout sophomore album that catapulted him to stardom, while keeping his identity a mystery. Released under MDLBEAST Records, the white crochet masked singer’s album was quite literally everywhere, the album cover of him against a pink backdrop offering you a red rose plastered on every other Instagram Story. Sonically and visually, Cocktail Ghena’y had all the makings of a hit: accessible yet polished, steeped in 90s and Y2K Arabic pop tropes. But what truly set it apart was how effortlessly it made Arabic pop feel fresh again.

With a slew of social media-savvy bedroom artists and producers on the rise, and an Arab independent music industry in its infancy stages, this literal change in tone acts as a cautious beckoning, a “let’s see what sticks” approach of defining the next evolution of the region’s pop music identity. “We’re still learning, but [the artists] who do stand out are the ones who are consistent, and who [understand the importance of quality in the music and visuals],” El Mendelek tells ICON MENA.

One of the most striking new standouts in Arabic pop is 22-year-old Egyptian artist Nour. Following her 2023 debut EP Daydreamer, she made waves with solo single Wana, a dreamy blend of bedroom and synthpop, layered with playful, meditative production by Egypt’s “modular synth maestro,” Kubbara. The track racked up millions of streams across platforms, and the reaction was immediate and somewhat singular: “I’ve never heard Arabic music like this,” one YouTube comment reads under the music video, which was directed by filmmaker Mazen Bayoumy. Integral to the song’s success, said music video sees Nour staring unamused into a fish-eye lens with a white studio backdrop punctuated with colorful Rubik’s cubes and children’s building blocks, all while she croons about a love that’s left her disillusioned and jaded. It’s refreshingly soft, quirky, dreamlike, and understated.

Many of her contemporaries tread similar sonic ground, but Nour’s ethereal aesthetics, marked by her purple-streaked hair, and her blend of UK garage beats with introspective Arabic lyrics and rhythms, make her stand out. Her vision looks and sounds hyper-local yet unmistakably shaped by the internet, bridging many sonic references with a sound that’s both nostalgic and refreshingly new. Think PinkPantheress or early Clairo circa 2018, but you don’t need to get the references to admire the novelty in what Nour is presenting.

She followed up Wana with a more fiery release under MDLBEAST Records, NOGOUM, another introspective cut of bedroom pop and drum and bass. As the chorus swells with wobbly synths and pulsating percussion, Nour’s singing has a bit more bite than usual. She sounds louder and grittier, which is fitting of the anxiety-fuelled subject matter on the track. It’s pure pop through and through.

Nour’s breakthrough has positioned her as one of the most exciting new voices in Arabic pop. In her interviews, the young singer is clear in her vision for the region’s music industry, emphasizing the importance of having more fearless female artists who embrace experimentation with their sound. Fortunately, the movement she envisions is already in motion, because the girls are already here, pushing boundaries independently, and perhaps venturing a bit too left-field for the average listener.

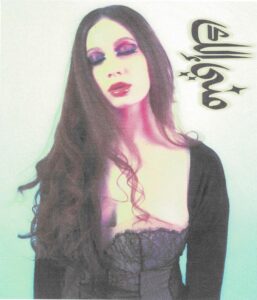

If she has ever popped up on your feed over the past year, you instantly get the feeling that she’s unmissable. London/Dubai/LA-based Lebanese singer MARCELINA has had quite the journey over the span of her short career, shapeshifting and genre-hopping along the way. Her approach is no-holds-barred, with an attitude that could send a crack down your screen if you look for too long. Last year, her song Leila thrust her into a new spotlight, a dancy jersey beat-driven track accompanied by confessional writing about the push-and-pull of a hot-and-cold relationship. The jump between the Arabic verses and the English chorus feels seamless, delivered with a soft, mesmerising cadence. Leila opened a new door for MARCELINA, as she tells ICON MENA, helping her connect with an audience that understood her vision. “I wanted to create a sound that I hadn’t heard [in Arabic] before,” she explains. And by many accounts, she succeeded.

Undeniably, the mysterious world she built around the song played a part in drawing that crowd in. In one of the promotional images for the track, the singer is laid out on an asphalt road in full Leila character, wearing a corset with pleaser heels scattered by her side. The rollout campaign, entirely self-curated like all her visual work, reflects an artist who sees their imagery as an extension of the music.

MARCELINA’s inspirations are as eclectic as her sound, spanning from the avant-garde experimental American multi-instrumentalist Eartheater to pop queen Elissa, a contrast that could be the secret to her undeniable pull. It’s a fusion that feels both unexpected and effortlessly natural. Take Kisses, a track she released shortly after Leila. A sharp-eared listener might catch a fleeting echo of Elissa’s Aayshalak in the second verse. It’s a subtle yet intentional nod to the Y2K pop icon, and proof that MARCELINA knows her Arabic pop.

With her SoundCloud beginnings in the rearview mirror, the artist continues to grow her presence in the regional music scene independently, navigating the record label system cautiously, in a way that puts her artistry first. “Any label I [would potentially work] with has to understand my vision,” she affirms.

Lebanese singer LAÏ is another artist with an unwavering vision, one that has built her a dedicated following and over a million streams in just four years. Her journey began quietly, with a handful of tentative self-produced bedroom pop releases, but she wasted no time making big moves. In 2021, she relocated to Cairo, securing collaborations and production credits from the likes of Egyptian producer El Waili early on. Her mixing credits even include Kiri Stensby, a music producer and audio engineer who has worked with the likes of Eartheater, Shygirl, and Caroline Polachek. There’s an admirable quality to the singer’s determination. “I just send emails, I take risks… I’m an email girl, I’m a DM girl, I don’t think anything is out of reach,” she tells ICON MENA.

As a film director and editor as well, she’s at the creative helm of all her work. Every song has a thorough visual concept. In the self-directed video for Shabah, she drifts like a spectre through the halls of an eerie mansion. In Sekkin, also self-directed alongside Georges Matar, she is bathed in the glow of blood-red curtains, wreaking havoc. It’s a visual indulgence that adds more depth to the themes of anger and isolation that run through her songs.

LAÏ’s sound cannot really pinned down, but she doesn’t care to pin it down. “I’m a genre-less artist,” she quickly answers when I ask the question. In her last couple of releases, the previously mentioned Sekkin and Khatwa L’Wara, she takes on a more abrasive sound and Arabic spoken-word approach. The beats, courtesy of electronic music producer Nader Khalil, are deeply bassy and aggressive, and the artist packs the punches accordingly. In her latest release, she jumps on a feature with Algerian artist Losez on HASNI 1993. Her verse is electrifying, riding a flurry of synths as retro video game sound effects go off around her voice. The track blends many genres, but what shines through to me on her portion of the track is a sound reminiscent of the effervescent post-2020 hyperpop sound. It’s a definite highlight in her discography.

With her debut album in the works, I can’t help but ask what she sees the future holds for her. However, I very quickly realise that one thing is clear: she has no intention of softening her sharp edges. “I could have gone much more commercial [with my music] and had a million streams already, but that’s not my goal, it’s not my craft,” she answers confidently. “In 6 or 7 years, maybe my music will make more sense.”

On surface level, that answer could sound a bit deluded. But, with a music industry that’s growing and experimenting, and a young audience that is becoming more receptive to new and more melodic Arabic sounds, along with the marketing-savvy artists promoting them, it’s not so hard to believe. “Pop is going to have its moment now [over the coming few years] with the likes of TUL8TE,” El Mendelek predicts. “But after that, we’re definitely going to see a wave of more experimental genre-blending pop artists breaking out.”

In many ways, that moment is seeing its beginnings now. It may be labelled as “niche” and “weird” by your average music label exec, but some of the most interesting Arabic music already exists online, and it’s getting way less hard to find. The independent music industry is catching up and audiences are keen on hearing something new. The numbers show it, at least. If you get the vision, great. If you don’t, I’ll echo the sentiment that maybe you will a few years down the line.

WORDS: Hady Afif