News

Beirut has long been a playground for the foreign imagination, the eternal city of the phoenix and accompanying metaphors. Every few years, journalists parachute in to describe its “resilient nightlife” and draw some tired parallel between the sound of bombs and bass. War-torn yet dancing. Ravaged yet reborn. Arab yet globally attuned and strikingly transgressive. Beirut, the metaphor. At this point, even dissecting that trope feels exhausted and overdone.

For most of the 2000s and 2010s, Beirut’s underground (read nightlife) captivated the outside gaze. Venues like B018, which closed down due to financial mismanagement last year after an over two-decade run, became fixtures of that fascination, drawing easy and uninspired Western comparisons. Of course, part of that intrigue stemmed from its setting: a subterranean bunker under a desolate plot of land that had historically sheltered different waves of refugees. The mythology is rife, but evidently inescapable.

Even the terms “underground” and “alternative” now feel dated, fetishised as symbols of authenticity, then diluted by global platforms, branded spectacles, and corporate tours that accelerate the Boiler Roomification of subculture into content. So, in this context, the so-called underground is simply a network of small, self-made DIY spaces existing outside the state-sanctioned revival of post-civil war Lebanon.

The last few years in Lebanon’s latest chapter of collapse have rewritten the conditions of living and creating in the country. Mass protests, a massive explosion that left half the city in ruins, economic freefall, and mass emigration, all thoroughly documented outside the confines of this piece, have left much of the city defaced. Entertainment venues shuttered, and even the most basic logistics of power, fuel, and internet became unpredictable. What endured did so out of sheer stubbornness. So, in the state and private sector’s parallel narrative of “revival,” it’s hard to imagine an underground music scene that could merit anything close to a headline tailored for outsider fascination (this one not included). That’s why landing on Dajjeh’s Instagram page for the first time felt both exciting and intriguing.

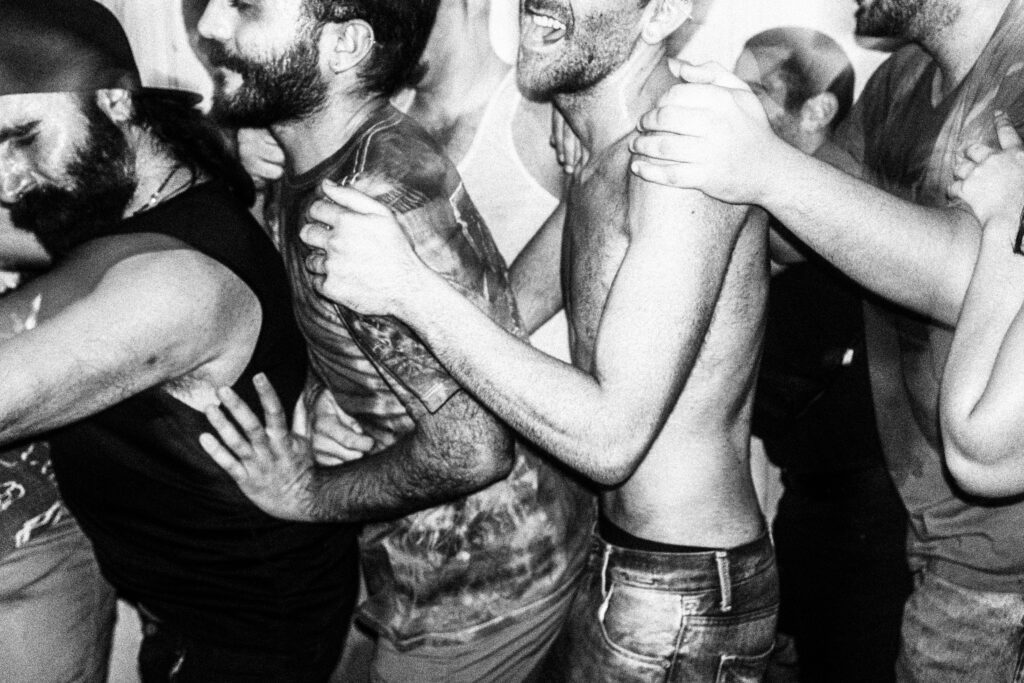

Dajjeh (“loud noise” in Arabic) is a seven-person punk collective that emerged in Beirut in early 2024. Their shows are often held at Zico House, a nearly century-old residence in Sanayeh that has long doubled as a home for artists, activists, and independent cultural initiatives. They borrow their gear, split losses among themselves, and host roughly 200 people for each show, always for free. DIY to the core.

This surge in punk and adjacent sounds feels noteworthy, mostly because, as a genre, it has always been overshadowed by the city’s more exportable sounds. Electronic music in particular has dominated Beirut’s alternative media circuits and nightlife spaces for decades. Punk, by contrast, has a more spotty history. Beirut’s alternative music scene is anything but formally documented, which makes Dajjeh’s emergence in 2024 the sprout of a seed planted many, many years ago, particularly in the second half of the 2000s.

“Some of us saw the scene back then, and we’re not all that young. There were a lot of great bands, but over time, things got quieter, with the economic crisis, revolts, people leaving, and musicians going in other directions. In general, punk here has always been smaller than metal, rap, or noise, which is still true,” Racha from Dajjeh tells ICON MENA. “When we started Dajjeh, we reached out to some of them, and one band even came back to play. Some of the old audience also come to our shows.”

“The scene back then” is documented by researcher and artist Lynn Osman in her 2015 auto-ethnographic research project Are the Streets Still for Dreaming? and its later 2022 expansion for Rehla Magazine, through which she traces the roots of Beirut’s punk, thrash, and metal movements in the city’s 2000s post-war landscape. She documents how bands like Damaar, Detox and Thrash Storm, together with early skate collectives, carved out temporary zones of autonomy in a city divided by privatisation and sectarian lines. Much of it revolved around spaces like the long-gone Pavillon centre, a key venue in Hamra that hosted metal and punk acts of the late 2000s, where the scene’s short-lived golden age played out. By the early 2010s, much of that energy had faded, mostly due to the aftermath of the country’s 2006 war with Israel. Venues closed, musicians emigrated, and others turned toward religion or different creative paths. The economic and political crises that followed eroded what was left of the infrastructure that had sustained the scene. Osman’s research is a rare glimpse of a scene that didn’t leave much behind, mostly hidden even in its heyday.

It’s easy to write about Beirut’s alternative music scene as some kind of monolithic entity, both in genre and space, so that is absolutely not the intention here. Its actors have always been few in number yet deeply intertwined, both historically and today. Swiss ethnographer Thomas Burkhalter’s Local Music Scenes and Globalization: Transnational Platforms in Beirut was the first study of its kind, an impressive, and extensive, decade-long ethnography (2001–2011) that offers a grounded record of how the city’s alternative musicians, many of whom grew up during or just after the fifteen year civil war, built a loose scene from disarray. Burkhalter notes that the lack of documentation only adds to the confusion, writing that “Beirut lacks continuity and a transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next.”

Beirut’s earliest alternative impulses appear briefly in his account, with the 1960s described as “the cradle of alternative music.” Amid campus strikes and growing solidarity with the Palestinian struggle in the aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, music started to steer away from the state-promoted optimism of the Rahbani brothers into something more subversive. At the time, a handful of Lebanese bands were experimenting with imported sounds, most notably The Sea-Ders. Formed in Beirut in the mid-1960s after its members met at the still-standing Chico’s Records in Hamra, the band became part of the city’s brief flirtation with the global psychedelic rock movement. They later signed a short-lived record deal in the UK, rebranding as The Cedars, before fading into obscurity after failing to gain commercial traction.

The researcher’s fieldnotes are rich, painting a comprehensive picture of a scene whose many names are still active today. At the core of the experimental movement, artists like Mazen Kerbaj and Sharif Sehnaoui turned improvisation into a solid medium, transforming the city’s soundscapes and dissonance into Irtijal, which continues to this day as Beirut’s longest-running music festival. Simultaneously, the rap circuit, with voices like Rayess Bek (Wael Kodaih) and his duo with Houssam Fathallah, Aks’ser, turned multilingual wordplay into mouthy social critique. Aks’ser’s brief signing to EMI Arabia marked one of the earliest attempts to commercialise Beirut’s underground rap, a genre which generally remains more popular commercially today. Fadi Tabbal and Charbel Haber, then part of their band Scrambled Eggs, experimented with noise and rock performed in English, forming the abrasive backbone of Beirut’s indie ethos at the time. Tabbal would later anchor the scene institutionally through Tunefork Studios, founded in 2006, which remains the city’s go-to recording and production space for alternative acts, and Ruptured the Label, co-founded in 2008 with radio host and DJ music promoter and producer Ziad Nawfal, which continues to document and distribute the overwhelming majority of the output. The urban-electronic front, led by Zeid Hamdan and Yasmine Hamdan’s Soapkills, among others, layered Arabic tonality over electronic synths, producing some of the very early explorations of the genre and defining a nostalgic “Beirut” sound in the process. Zeid and Yasmine would eventually become among the first of this generation of artists to receive international acclaim, with Yasmine recently releasing her third solo album, I remember I forget, in September of this year.

One of the clearest signs of the book’s age is Burkhalter’s description of Mashrou’ Leila as up-and-coming (the band’s members are younger than most musicians mentioned in his research). The band embodied what he called a “new Lebanese middle ground,” with alternative rock sung in Arabic, pushing the city’s experimental underground out of the cracks to reach a wider regional audience. What he vaguely predicted came true, as the band would become a regional cultural phenomenon by the mid-to-late-2010s before disbanding. “We are not the generation that will make it; we prepare the ground for the next generation. Mashrou’ Leila plays in front of three thousand people. Soapkills got like five hundred, and this was already wonderful for them,” Burkhalter quotes Tabbal saying in one of their interviews.

The 2010s generally saw more support for alternative music in the country. Brands like Red Bull and Jameson were at the forefront of this branded support, sponsoring bands and hosting massive events like 2013’s Red Bull SoundClash, which staged a live musical duel between Mashrou’ Leila and Who Killed Bruce Lee, two of the biggest acts in Beirut at the time, in front of a crowd of 3,000. This era of the alternative scene is much easier to trace, thanks to the internet, and the fact that a lot of the acts that emerged during this time period are still prominent in the alternative music circles today.

Alongside this surge of corporate-backed interest in local music, other initiatives were taking shape on a smaller, more independent level. Founded in 2013, Beirut Open Stage (BOS) quickly became one of the city’s key launchpads for emerging alternative acts. The platform offered something rare at the time, a unified space where emerging artists from across genres could share a stage. Its lineup over the years featured Zeid Hamdan, The Wanton Bishops, El Rass, Postcards, Safar, and many others. Postcards, now Lebanon’s longest-running alternative band, went on to tour internationally and release multiple albums, while one-half of Safar, Mayssa Jallad, has since built a solid solo career. After expanding into a physical venue in 2017, BOS eventually shut down due to a lack of funding.

“Between 2010 and 2015, there was a boom in indie music. Big brands always had bands playing at festivals and Mashrou’ Leila were still at their peak,” Postcards’ frontwoman Julia Sabra, who at the time of writing is in the middle of a tour for the band’s latest album offering, Ripe, tells ICON MENA. “Now, after the financial crisis and the explosion, things have gone back to being more DIY. BOS was great because it gave a space for new and old bands to connect. It was us [and our peers] playing alongside [other established acts.] There was a more formal place to exchange with other bands. Now you either play at small bars or at Metro Al Madina, which is a lot of pressure because [you have to guarantee a big attendance]. Artistically, however, it’s a great time for bands, I would say. There is no longer this pressure to make it into the ‘mainstream.’”

Sabra describes a growing sense of continuity within Beirut’s independent scene, something she says was missing when Postcards first started. “When we came up, we didn’t know who came before us,” she recalls. Now working as a manager and engineer at Tunefork Studios, she credits Tabbal and the studio itself for bridging that gap and nurturing a real lineage between generations. The pipeline is still young, two decades in the making, but new acts emerging today know exactly whose shoulders they’re standing on.

In a city where collapse and rebuilding are a semi-annual routine, describing anything as a full circle either feels naïve or just simply historically inaccurate. So, the history lesson feels essential. Still, Dajjeh’s emergence as a DIY space for young bands feels like a return to form, a proving ground for Beirut’s post-COVID generation to shape its own underground sound.

“We were friends first and felt that Beirut was missing punk, so we decided to try putting on shows ourselves. The first one was at a friend’s house. About 30 people came. It was only recorded music, but that’s where the collective kind of started,” explains Racha, the Dajjeh organiser. “We met an older veteran of the music scene who used to run a venue before it went out of business. He let us use his PAs, mixer, cables, and put us in touch with Zico (Mustapha Yamout), who let us use the space free of charge. We made posters, and people showed up. 30 became 60, then 200.”

What started as an attempt to host strictly hardcore punk shows quickly evolved into something freer. With few punk bands left in the city, Dajjeh opened its doors to metal, noise, grunge, post-punk acts, and essentially anyone who shared the same DIY ethos. Even noise and electronic acts joined in, shaping their sets to match the room’s energy.

Said energy is nothing short of pure unfiltered release, and it is embodied by ta2reeban (“almost” in Arabic), a hardcore trio whose members, Charchour, Roupen, and Michael, first met at Dajjeh’s founding house show and remain central to the collective. Their debut EP, صاحب الموتور بيستند عليكن (The Generator Owner Is Counting on You), was released in September 2024. The vocals are flat, shouted in Arabic, half-detached, yet charged with a mix of irony and sharp self-awareness. The result is both feral and disciplined, averaging at around eight minutes total. Looking at the tracklist, قتيلة أطفال (Child Killers) is an immediate standout. The main chant throughout the track is a refrain of “we will see the end of capitalism, we will see the end of zionism.” The subject matter is timely and knife-sharp.

“We started [the band] in February of last year, so the war had already started here. The genocide in Gaza had already started. We were five years into the economic crisis, which is truly not over. We’re reacting to things around us, the things that we’re thinking about. It’s a balance between reacting to your context and thinking about what’s happening around you, but also not just writing lyrics that are basically tweets responding to something so immediate and short-term,” the band’s Charchour tells ICON MENA. “It comes pretty naturally to us. We’re not trying to tell anyone anything that mind-blowing and profound. We’re just giving voice to things that a lot of people in our lives also feel. It’s stuff that we all know, we’re just giving it an intense beat, and a really loud riff, to say how we feel about it.”

The band was initially set to celebrate their debut with a release show in the same month, but Israel’s escalation in its ongoing war with Lebanon, which increasingly targeted Beirut specifically in the last 3 months of last year, forced them to postpone it to February 2025. A year later, the band dropped their second EP, Nancy, in September 2025, announcing it on Instagram with a tongue-in-cheek disclaimer: “It’s even shorter than the first one, so you got even less excuses not to support.”

This time, ta2reeban ventures into more melodic ground, blending hardcore with the rhythms of their mother tongue, drawing on surf punk influences inspired by Lebanese-American guitarist Dick Dale (Richard Anthony Mansour), who famously translated derbake (Arabic hand-drum) rhythms into his signature rapid-fire guitar picking style. “And to be clear, we’re not playing fusion. We’re playing hardcore with a lot of these influences in mind,” Charchour affirms. That shift is immediately heard on the opening track اكيد خسران (Definitely a Loser), a track that, when compared to the band’s earlier work, comes with uncharacteristically pulsating rhythmic sections. Too Slow, the second track, one of the band’s slower cuts, allows enough breathing space for the listener to make out the lyrics without squinting too hard. The opening paints a vivid image of the broken justice system, or lack thereof, in a country like Lebanon, and the injustice it breeds: “I saw your brother yesterday, he’s been imprisoned since high school. You have no wasta or money, it’s a good thing they let you get him a plate of freekeh.” استفراغ (Vomit) features actual singing for the first time in ta2reeban’s discography. Themes include exhausted mental health and the numbing repetition of waking up to the same day over and over again.

The quick turnaround for both projects in the span of less than two years was made possible by support from Tunefork; all it took for the band was to get in contact. “We knew the guys over at Tunefork, Fadi Tabbal and Joy Moughanni. They were really amazing and supportive, and encouraged us to kind of come to the studio and put them down, at a discount, let’s say,” Charchour explains. “I don’t think we would have gone anywhere else. Tunefork is the beating heart of the alternative scene here, as far as studios go.”

The studio’s portfolio today reads like a list of the biggest alternative names to come out of Beirut in the past 10 years, from more established acts like Kinematic and Sary Moussa, to more recently founded acts like SANAM. Among the listees is Bliss, one of the city’s youngest grunge bands, the spiritual successor of Postcards and a band that has done its time at Dajjeh, despite their softer and dreamier sound compared to the average Dajjeh act.

Bliss was born at the American University of Beirut in 2022, when its three members met through the university’s Music Club. After the pandemic drained campus life, they revived the club, turning its practice room into their main stage. Their first gig came that December at Hazmieh’s long-standing music bar, Quadrangle, a show that caught producer Tabbal’s attention after a last-minute email invitation from Julie. This resulted in a production session scheduled a few weeks later. Before the start of their spring semester, their five-track debut EP, You Should Quit Your Job And Play Outside (With Me), was recorded in lightning speed over a week and a half and released in April 2024.

The band’s Gen Z sensibilities are impossible to miss, from their quirky Instagram feed filled with grainy digicam shots and chaotic captions to the endearingly long debut title and a Bandcamp page declaring “FADI TABBAL IS THE GOAT.” However, you shouldn’t confuse the playful energy for simplicity or lack of sophistication. The sound of their debut alternates between calm slow burning stretches and sudden lifts, with the standout track, Feel Better, featuring a beautiful vocal performance from the band’s vocalist. Her voice is stretched and slightly distorted as it soars over a simple percussive drum beat and gritty guitar on the chorus. “All I ever wanna do is see you smile,” she repeats. The heartbreak, longing, and nostalgia seep through the other tracks on the EP.

Listening to the band’s newer releases doesn’t reveal much change in direction. The calm-to-soaring patterns of their first EP simmer into restraint on Me After Telling Him I’m Cool With Whatever, their slowest and most muted track to date. It’s a showcase of a tightened, more simplistic sound. And it’s quite emotionally direct. “I’m glad I met you,” Julie sings, distilling the song’s sentiment quite simply. It’s bittersweet and stings in all the right places. The appeal of their music is universal, but is tinged with the sentimentality only a 20-something living in Beirut in 2025 could conjure up.

“Our music connects with people everywhere, but the ones who really cling to it are people our age living here in Lebanon. Maybe it’s because they’re just like us, and they hear something familiar in it,” Julie tells ICON MENA. “Nostalgia is maybe our biggest inspiration as a band. We write songs that honestly feel like something my 13-year-old self would have obsessed with. Even outside the music itself, the way we dress, the grainy digital camera pictures, the 2000s aesthetic. It all elicits a kind of sweet sadness, that brief moment in our childhood when the country was doing well. Lebanon was peaking, and things felt like they were going to be alright. I think most of the youth in Lebanon want to chase that fading feeling. That sense of longing is everywhere in our songs.”

The past year of war in Lebanon has tested nearly every musician working from Beirut, making any sense of stability feel even more out of reach. During the escalation of Israel’s attacks, both bands shifted their focus entirely, pausing their music to take part in mutual aid efforts to support communities hit hardest by the violence. Recording sessions fell to a halt. For Bliss, the pause hit even harder when their drummer left the country, leaving the band to regroup and bring in a replacement, Andrew. “Being an artist here can feel isolating,” Julie admits. Still, the work continues. At the time of writing, ta2reeban are preparing for a back-to-back European tour, and Bliss are piecing together their next album, set for release by April 2026, accompanied by a European tour.

In the most recent, and youngest, wave of Beirut’s underground music scene, what’s becoming feels smaller and more deliberate, but all the more louder. What’s emerging is a reconfiguration forced out of the present conditions, one that foregrounds artistry and communal acting. Today, acts like Snakeskin (Tabbal’s duo with Sabra), SANAM, Postcards, Mayssa Jallad, and others are touring beyond Lebanon, a striking contrast to the couple of bands doing the same just a decade ago. Back home, Ruptured the Label now commands attention from the likes of Pitchfork and Bandcamp, its catalogue attracting more global attention.

And at the risk of propagating anything that borders on a narrative of resilience, it’s safe to say that none of it is all that glamorous. But the noise carries on, despite it all. To put it in Sabra’s own words: “It now means something to be a band from Beirut.”