News

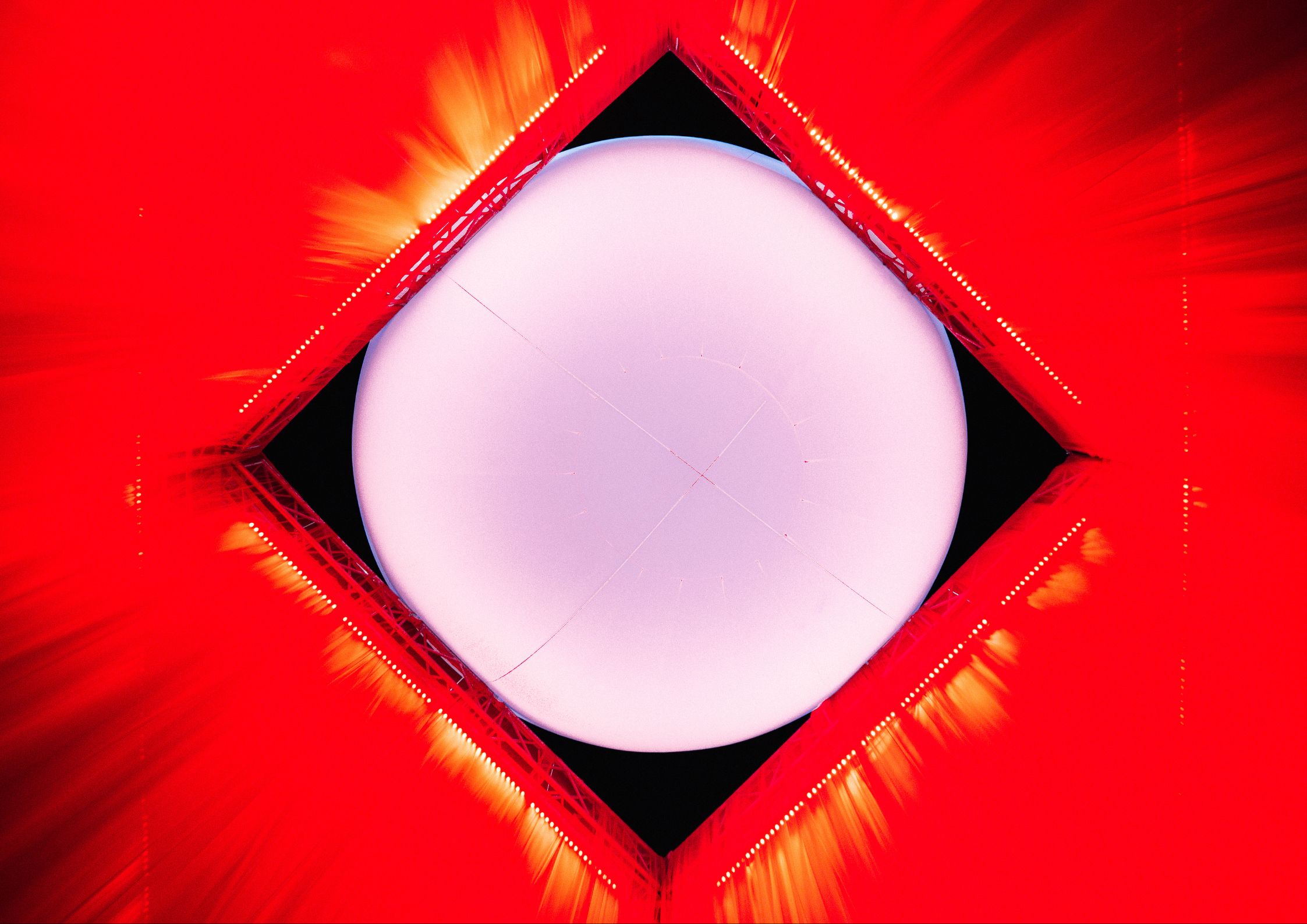

Fuad Ali’s voice crackles through my phone as I weave through Al Shindagha’s narrow alleys. “You can’t miss it,” he says, and he’s right. Before I can even meet Duette Studio in person, they’ve already announced their presence. There’s a pearl in the sky!

Duette Studio functions as a multidisciplinary creative lab born from the long-standing partnership between designers Fuad Ali and Rahat Kunakunova. Their work moves fluidly between designing and producing live installations, editorial direction, branding worlds, and spatial storytelling. From the immersive Petunia Gardens at D3 to the scenography behind major beauty campaigns, including Huda Beauty launches, and large-scale collaborations with ASICS in Riyadh, to now the Pearl Majlis commissioned by Dubai Culture for the Sikka Festival, Duette is making its presence felt regionally.

For the duration of the Sikka Art & Design Festival, which returns to the historic district from January 23rd to February 1st, Al Shindagha transforms into a living, breathing hive of courtyards, rooftops, and doorways dedicated solely to the shared practice of art, design, performance, music, and conversation. Sixteen restored houses host works across visual art, photography, ceramics, public art, technology, and urban culture. The festival’s curatorial direction this year centers on themes of reflection: how the city remembers its past while imagining what comes next. It is within this territory that Duette Studio’s Pearl Majlis welcomes us.

It feels fitting, then, that my conversation with Fuad and Rahat takes place inside The Pearl Majlis itself, their debut at Sikka Art & Design Festival, a structure conceived for the sole purpose of communal gathering. A majlis, after all, is not designed to be simply looked at but to be inhabited: a space where people can sit together, linger, listen, exchange ideas, and belong.

The Pearl Majlis is made visible long before you reach it: a softly glowing sphere suspended within a canopy of red fabric, hovering between old coral-stone houses and the slow shimmer of the creek. Installed at Al Shindagha Museum’s Public Art House 436 and commissioned by Dubai Culture, Duette Studio’s Sikka debut is composed of a central spherical form, the “pearl”, softly illuminated, its surface subtly shifting in colour as night falls, resting within layers of red textile suspended above and around, reminiscent of curtains.

The installation feels like a reimagining of a mythical aquatic organism: porous, permeable, in constant dialogue with wind, light, and bodies passing beneath it. Rather than appearing as a fixed structure temporarily dropped into the city for a festival, it feels like something that has briefly taken up residence here, learning the rhythms of Al Shindagha as much as we are learning to navigate its own. By day, the fabric filters harsh sunlight into a gentler shade; by evening, the pearl glows from within, casting a low, atmospheric light that draws people inward. The red drapery moves constantly, responding to air currents, forming new pockets of enclosure and openness. The majlis always beckons.

This mutability is intentional, sitting at the heart of the installation’s conceptual framework. The pearl, in the UAE, is not simply a neutral, decorative motif; it is historically dense and mythologised. Long before oil reshaped the Gulf, pearls sustained entire communities. For centuries, pearl diving structured coastal life across the region, shaping kinship networks and seasonal rhythms. The pearls themselves circulated globally, appearing in Roman markets, Byzantine records, medieval Islamic texts, and the travel accounts of figures such as Ibn Battuta. They are dense with layered meanings: economic, historical, emotional, and symbolic, belonging simultaneously to lived experience and national mythology. Their meaning has never been fixed. Duette’s gesture is not to stabilise it but to reopen it to interpretation.

Spending time around the Pearl Majlis makes clear that objects don’t arrive with fixed meanings, they accumulate them. Philosophers have long tried to separate what a thing “is” from how it is used, but in real life, that distinction doesn’t hold. Meaning is shaped by memory, by context, by who shows up and what they bring with them. Here, that happens in real time. Visitors reauthor the installation: someone tells Fuad they want to shoot wedding photos beneath it; World of Gunk, an independent print publication, hosts “The Gunk Hour,” panel discussions sharing intimate insights; and on January 29th and 30th, AlMultaqa musicians, rooted in Afro-Arab heritage, will perform live in collaboration with The Baranda from 8-9 PM.

![]()

The installation invites lived interpretation rather than prescribing meaning, resisting the familiar logic of art spaces that instruct you where to stand, what to read, what not to touch, and when to move on. It subtly resists the idea of heritage as a static narrative, reinforcing the truth the pearl itself has always embodied: its meaning is never fixed but continuously reshaped through usage, memory, and lived experience. Heritage narratives are important for understanding the past and present, but as anthropologist Jaume Franquesa notes, heritage is never neutral; it is constantly being shaped. Duette proposes a heritage that remains porous, unfinished, and collectively collaborative.

Instead of presenting the pearl as a distant symbol, Duette transforms it into a welcoming space. The installation doesn’t instruct you on how to feel; it invites you to live in it. Children run in and out of the drapery, friends bring takeaway and linger beneath it late into the night. None of this was planned, yet all feels aligned with the work’s ethos. Rahat reflects on the deliberateness of this openness: “In commercial spaces, everything is controlled,” she shares. “We intentionally design how you move, where you look, and how long you stay. With this, we wanted the opposite. Everything is very intentional. We want to slow people down. We designed the structure, and now we’ve let go. We want people to move within the space and make it their own. What they find within is what completes the work for us.” That surrender of authorship is rare in public design, particularly where public space is overly regulated.

Immanuel Kant once argued that objects are understood through fixed properties: form, function, and concept. Later thinkers have challenged this, suggesting meaning is never stable because memory itself is unstable. An object’s identity shifts depending on who encounters it, when, and under what conditions. The Pearl Majlis embodies this instability beautifully: it looks different at dusk than at noon, feels different when alone than when crowded, and means something different to someone resting beneath it than to someone celebrating or enjoying live music.

Materially, this philosophy is most visible in the red fabric that curtains the installation’s perimeter. The reference is to tbaba (تبابة), the traditional red cloth used to protect freshly harvested pearls. Here, it acts as shelter not for pearls but for visitors, providing a soft boundary, a space to pause, gather, and inhabit. Its texture and depth evoke the fluidity of the Gulf’s waters, folding and rippling with the wind as though the sea itself has been suspended above Shindagha. The movement is kinetic but not chaotic; it mirrors the rhythms of pearl diving—the rise and fall of bodies in water, the labor, the endurance, the careful choreography of extraction. Suspended above and around the structure, the fabric behaves like a living membrane: it catches the wind, ripples, folds in on itself, recalling water’s movement, the instability of the sea, and the rhythm of breath. Wind becomes a collaborator rather than an inconvenience, while the fabric also provides shade and airflow, cooling the space beneath. Conceptually, it performs what Duette Studios’ philosophy is concerned with: heritage is not fixed but constantly reshaped by environment, usage, and time.

The structure’s functionality is also deliberate. The canopy provides shade, redirects airflow, and creates benches through structural necessity. “In the start, the engineers said no, we can’t do this,” Fuad tells ICON MENA. “If we have such a large inflatable on top of this structure, the chances of the pearl flying off were higher. To prevent that, we needed three-ton boxes on each side. Now, that would look really ugly. We still had to find a different way. We kept challenging ourselves and asking the simple question of why not?” Even engineering constraints such as weight, anchoring, and safety were handled with consideration and accessibility in mind. In the end, they used a metal pillar and raised rock structure to provide benches for people to rest and keep their belongings.

In conversation, Duette Studio speaks candidly about their unorthodox process: negotiating with engineers, trial-and-error, and refusing to compromise.

“Maybe, if we had come from a traditional design background, we would have seen it as a challenge. We like figuring it out as we go. If we knew the outcome, what would be the point of our craft?”

“Not having the privilege to go to a good design school, I don’t know what the processes look like,” Fouad confesses. “We’ve learned through absorbing from other people and their practices. What you see on our social media is our attempt at leaving behind as many blueprints as possible. We didn’t start on fancy software, sometimes it’s just a sketch on paper or tissue. We even ask people to shadow us, to just come and see what we do, because everything we design and execute is unconventional. Lots of trial and error, lots of asking, Why not?” The Pearl Majlis, in this way, is not only a public installation but an extension of their pedagogical philosophy.

A personal favorite aspect of the Pearl Majlis is the atmosphere it provides. Within the hive of Sikka, the installation simply asks us to slow down, suggesting that public space can be something other than consumption, that it can remain a site of shared presence. As evening settles and the installation glows more intensely, there is little signage: no didactic wall text, no instructions on how to move or behave. “We design with intention, thinking of who we envision in the space, and that really is everyone,” Fuad reflects. “I know other places weren’t designed with someone like me in mind, an Ethiopian man, walking through, inhabiting their spaces.” The Pearl Majlis is a reminder that space can be poetic, that heritage is constantly reinterpreted, and that design can make room for those usually overlooked. Many installations in global cities today operate as spectacles rather than spaces, objects to photograph rather than environments to inhabit. The Pearl Majlis resists this logic. It does not seek to be consumed; it invites being lived in.

Walking away, I realise I am still orienting myself by the pearl, glancing back to locate it in the darkness, using it as guidance, just like a Northern Star.