News

In a memorable moment from his 2009 film The Time That Remains, Elia Suleiman sits silently on a balcony in Nazareth, a cigarette balanced between his fingers as Israeli fighter jets carve through the distant sky. He does not flinch. The scene is often described as a landmark in poignant, absurdist cinema. Poignant it is, but is it really absurd when millions in Palestine and beyond live in these exact conditions? When occupation and militarism have seeped so deeply into daily life that they are simply routine?

The Time That Remains, in this regard, is not unique. Indeed, in every single film of Suleiman’s excellent filmography, the Nazareth-born director uses silence, deadpan humour, and stillness to lay bare the barbarism of Zionist occupation. Yet the resonance is universal. Suleiman’s films echo around the world because they capture, with quiet precision, the condition of the Global South, where colonial and imperial violence is neither spectacle nor exception, but the ordinary rhythm of existence. What shocks in the West elsewhere is simply life. The unfathomable is the unremarkable; the dreadful, the familiar. Occupation, oppression and exile are, for the “Third World,” not tragedies but rites of passage.

But what does it mean to live like this, suspended between home and elsewhere? For millions across the Arab world and the Global South, that question is not rhetorical. From Ramallah to Algiers, from Tehran to Santiago, generations have come of age not in the shadow of a homeland, but in the long, dim light of its absence. In simpler words, exile is no longer rupture but genesis. It is the birthmark of the Global South itself. It is a shared inheritance of displacement, memory and survival.

So deeply is this collective condition entrenched that the dispossessed have channelled it to redefine art, language and belonging itself. Across continents, artists, filmmakers and poets have turned exile into form, into image, rhythm and word. Suleiman is one among many who resist the violence of empire through art that both mourns and reimagines. Their work does not merely lament what was lost but also imagines what might still be built from the fragments. To create in exile is to resist erasure. It is to transform dislocation into vision. Exile, then, is not where the story of occupation ends. It is also where it begins: the rite of passage through which a generation learns to see, to speak and to dream anew.

In Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, published in 2000, Edward Said wrote that exile is “the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home”. Yet what Said understood, and what has only grown clearer in the decades since, is that exile is not merely a consequence of war or displacement but a structure of being, a way of living in time. It rearranges everything: geography, identity, even memory itself. For the exiled, home is no longer a point of origin but a moving horizon, one that can be glimpsed, invoked and even performed, but rarely ever possessed.

This is why the notion of exile, and the far-reaching impacts displacement has on the psyche, cannot be understood as a singular rupture. It is a continual process carried across generations, reshaping not only where one lives but how one exists. The exiled inherit not just a memory of loss but a language built upon it, a dual condition that bends under the weight of translation, adaptation and longing. Said himself wrote in English, the coloniser’s tongue, using it to articulate a condition of displacement that transcended his own biography. So do I. That paradox defines much of the art born from exile, rooted in pain. “And while it is true that literature and history contain heroic, romantic, glorious, even triumphant episodes in an exile’s life, these are no more than efforts meant to overcome the crippling sorrow of estrangement,” Said also wrote in Reflections on Exile.

You can hear it in the music of the diaspora: in the auto-tuned melancholy of the searing hip-hop tracks penned by PNL, the immensely popular, trailblazing French-Algerian rap duo of brothers Ademo and N.O.S., where French, Arabic and street vernacular blur into a shimmering, borderless tongue, transforming fragments of fractured memory into haunting soundscapes. Even an accent, a borrowed phrase or a beat looped from a distant homeland becomes a testament to living between worlds without ever belonging fully to either. You hear it in Verlan, the back-to-front slang of the Parisian banlieues that turns language itself into rebellion. You read it in “Arabizi,” where Arabic slips into Latin script and numbers. And you feel it in the subtle inflexions of diasporic speech everywhere: the way you roll the letter ‘r’ differently depending on where you are, who you’re with, or what you’re trying to say, often without even realising it. Being from Pakistan, I know I do.

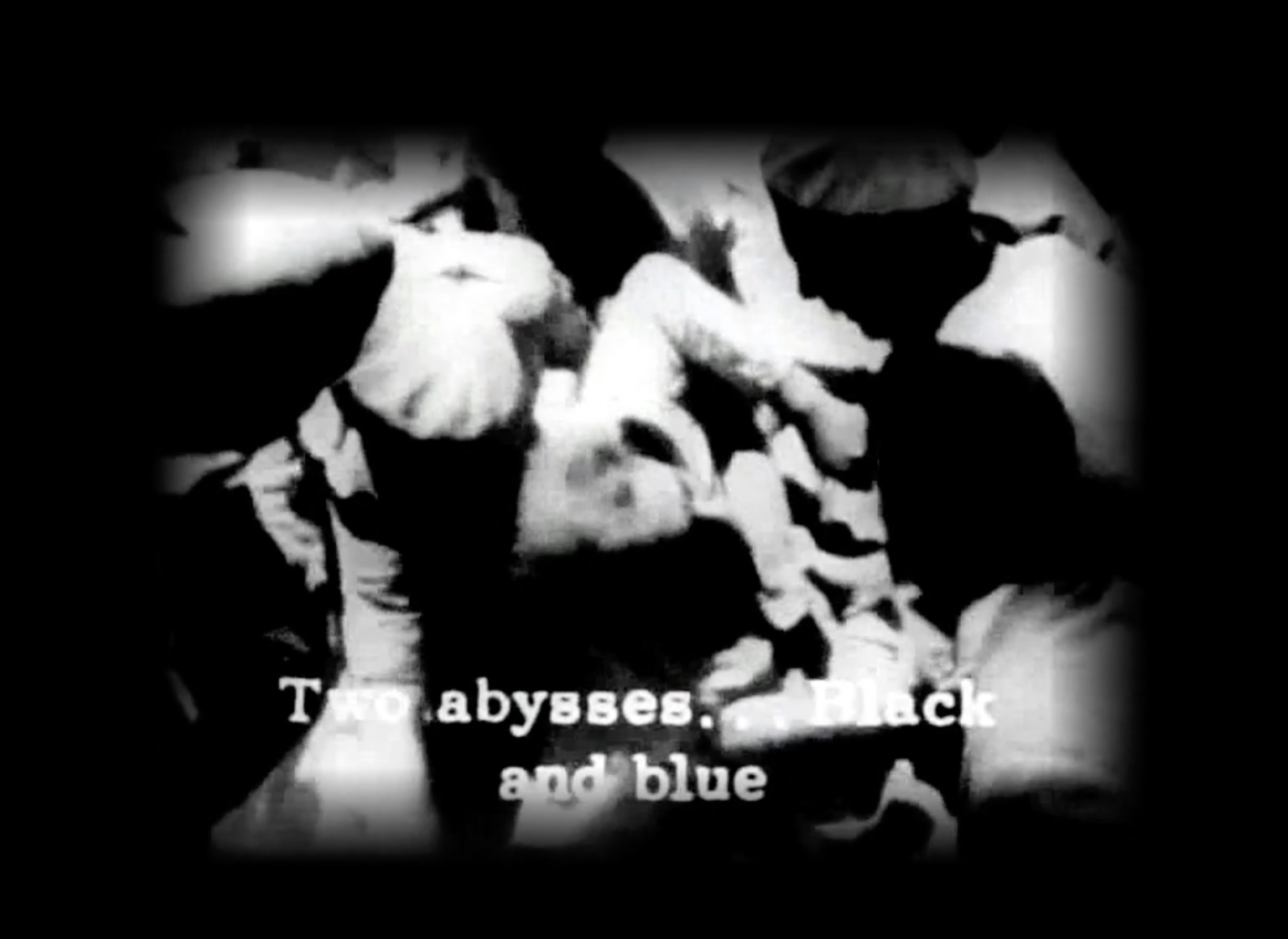

Cinema, too, carries this condition. In the works of filmmakers like the French-Senegalese auteur Mati Diop or the Palestinian artist Basma Alsharif, exile becomes a foundational language, a cinema of dislocation where the camera itself seems suspended between here and elsewhere. In Diop’s haunting film Atlantics, the ghosts of drowned migrants return to Dakar, inhabiting the living; in Alsharif’s affecting short O, Persecuted, fragments of Palestinian resistance films flicker across the screen like memory itself.

These efforts to overcome the crippling sorrow of estrangement, as Said put it, fracture identity to create new hybridities, new grammars of feeling. Out of fracture comes innovation; from loss, new vocabularies of art and belonging. And between languages, between sounds, between images, a third space emerges where the exiled can speak anew. Each is a small act of self-making, an attempt to reclaim an identity forged in the aftermath of a condition forced upon you. In this sense, exile is not the end of home but its reimagining, a practice of world-making from the margins that finds collective resonance without losing individuality.

The preeminence of the art born from this oft-discussed rite of passage for much of the Global Majority should come as no surprise. After all, to inherit exile is to learn how to live in its afterlife: to speak its language, bear its silences and find one’s place among its echoes. Perhaps nowhere is this inheritance more visible than in Algeria, where, for many, liberation from empire offered a new kind of displacement. Where the struggle for independence did not necessarily end exile but, rather, transformed it from a physical dislocation into an internalised condition, a continual negotiation with the ghosts of empire.

Alice Zeniter’s evocative 2017 novel, L’Art de Perdre (The Art of Losing), explores exile precisely in those terms: as an intergenerational apprenticeship in loss. The novel traces three generations of a family, from before the Algerian War of Liberation to contemporary France, mapping how the unhealed wounds of colonialism and identity pass silently through time. Zeniter’s protagonist, Naïma, grows up in metropolitan France, fluent in French but estranged from the country her family was forced to flee. Her inheritance is of a home that exists only in recollection.

Zeniter’s remarkable novel also explores the double bind that defines Algeria’s postcolonial condition. It illustrates how displacement not only reshapes those who leave but also those who remain. Independence, far from delivering a stable homecoming, entangled the nation in new circuits of exile: economic migrations to France, ideological purges, and the exodus of artists. This is not to draw parallels between the coloniser and the colonised, nor between exile propelled by occupation and by decolonial nationalism, but to examine exile’s evolution as a perpetual condition of the Global Majority today. It is an example of what Frantz Fanon foresaw and wrote about in The Wretched of the Earth: decolonisation without decolonial freedom risks reproducing the very alienation it sought to end. Algeria’s revolution liberated its soil, expelled the coloniser, yet also inherited more than mere fragments of its conditioning. The result was a new estrangement, which, for some, led straight into the empire’s belly, and for others, a black decade.

Art, especially in recent years, has become one of the few spaces where this contradiction can be both felt and reckoned with. Contemporary Algerian art continues to probe that paradox, whether in the work of London-based photographer Zineb Sedira or Franco-Algerian filmmaker Mounia Meddour, whose acclaimed coming-of-age drama Papicha (2018), set amid the Algerian Civil War, resonates far beyond Algeria and France. Like Zeniter, these artists, and many others from formerly colonised nations, turn to the mirror of exile to reflect on identity and belonging. To call exile a rite of passage, then, is not to romanticise it but to recognise how it shapes those who pass through it, whose work shapes those who don’t.

Indeed, as a creative force, exile is perhaps as potent as the condition that necessitates it. This is particularly vividly felt in Iranian cinema, where censorship, surveillance and isolation have given rise to an entire language of exile. Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film (2011), for example, shot entirely in his apartment while under house arrest, is one of the most expressive testaments to this form of resistance. In it, Panahi recounts scenes from a film he’s forbidden to make, performing his own captivity with subtle irony. The result is both documentation and a stylistically groundbreaking work of art, precisely because it shouldn’t exist, yet it does: a consequence of exile.

Like Panahi, Mohammad Rasoulof, and Abbas Kiarostami have transformed restriction into an aesthetic principle. Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or-winning Taste of Cherry (1997) unfolds almost entirely within the confines of a car, its minimalism not a stylistic flourish but a condition of secretive creation under unrelenting censorship. In There Is No Evil (2020), Rasoulof, himself banned from filmmaking and travel, turns moral resistance into cinematic form, constructing a mosaic of lives shaped by state violence. Together, these filmmakers, along with scores of artists and musicians from Iran, demonstrate that creating under repression is to inhabit a form of internal exile, where distance and silence, too, are acts of defiance.

Iran may be a revealing example, but this inward exile permeates borders. For artists under authoritarian censorship, the artwork itself is often exiled, becoming inaccessible to the people for whom it is made, even as it is celebrated abroad. Saim Sadiq’s Joyland (2022), Pakistan’s first film to screen at the Cannes Film Festival, was banned domestically for its depiction of queer love. In a surreal example of irony, it became Pakistan’s official submission to the Academy Awards, even as it was restricted across the country itself. In Japan, Nagisa Ōshima’s In the Realm of the Senses (1976) was prosecuted for obscenity, its reels seized even as it toured international festivals. Even today, while accessible, the film remains censored in Japan. Both films became stateless objects, denied a homeland even as they’re celebrated abroad, reminders that art, too, can be displaced, forced to live elsewhere to survive.

Even Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven (2019), made after leaving Palestine, bears this estranged quality. Its tone is more subdued, its humour lonelier; the camera lingers longer on empty streets and fleeting gestures, as if testing the texture of exile itself. In leaving home, Suleiman ostensibly discovers another kind of distance, an example that exile remains a rite of passage even for the most established of auteurs, in some way, shape or form.

In all these works, exile ceases to remain a theme; rather, it exists as the very fulcrum of its creation. The artist, like the displaced, learns to build meaning from fragments, to craft visibility from erasure. And if the Arab and Iranian experiences of exile expose their emotional and political scars, then Latin America, South Asia and Africa reveal their endurance.

In Chile, filmmaker Patricio Guzmán has spent years creating cinema from exile, forced out of his country following the brutal US-backed coup d’etat by Augusto Pinochet, transforming memory into a powerful force of rebellion. Since returning to Chile after over two decades in exile, he has made films in which he reckons with the scars inflicted upon the Chilean people by the dictatorship. In Nostalgia for the Light (2010), he explores landscapes haunted by dictatorship, insisting that remembrance is a political act. In Kenya, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote Decolonising the Mind during his 22 years in exile, due to threats to his life from the Kenyan government. He abandoned English to write in his native Gĩkũyũ, turning language itself into a form of resistance. And across South Asia, the ghosts of Partition still haunt literature, poetry and film, each tracing how the borders carved by empire continue to shape lives, collective memories and communities.

What binds these works together is not geography or even distance, but a sense of universality, one that creates meaning, solidarity and understanding across borders. Exile demands constant decoding: of language, of culture, of self. Yet from this deciphering, something new emerges. The displaced learn to speak across histories and continents, crafting hybrid forms that defy containment and transcend boundaries. What empire sought to scatter gathers anew.

In our present moment of endless wars, climate catastrophe and collapsing borders, exile has become the shared horizon of the century. But within this condition lies a fragile hope: that dislocation might yet give rise to solidarity. Exile is a rite of passage that has been forced upon millions of us by empire; yet it is also a continual becoming from which we build anew. With diasporic art, the blending of languages and rhythms, the persistence of memory against erasure, we glimpse fragments of that collective refusal, a determination to belong everywhere precisely because we were denied belonging anywhere.