News

When people migrate, they carry with them sound systems, street slang, and entire cultures. Each wave of movement from the Middle East and North Africa has left its mark on global pop culture, rewriting genres and creating new ones. Raï’s collision with French synths and drum machines in the 1980s, Somali rock experiments in the 1970s, Arab-infused Jazz, or today’s DJs shaking European clubs with Levantine rhythms. It’s a story of how migration rewires dance floors, headphones, and imaginations, turning exile into anthems.

While in Lagos earlier this year, I came across a work titled “The Freedom Deficit” curated by Between the Borders—an open collective of people with and without citizenship in the UK. It is a series of poems, photo collages and collaborative pieces, focusing on the discourse of migration and people movement. The piece that stood out the most was the one about the Kru People, an ethnic group indigenous to the south-eastern coastal areas of Liberia.

The Kru were the most widely employed Africans on naval and trading ships, hence where the name Crew was derived from. The Krumen’s leisure time, both on board ships and in the ports, gave them occasion to tell tales and play music. Thanks to travels and interactions with different peoples, the Kru gathered unique stories and were exposed to new experiences and ideas. They also gained wealth, which allowed them to acquire goods, most notably musical instruments such as accordions, harmonicas, and, most importantly, the acoustic guitar.

The Kru’s songs were vastly influential. Singing in Pidgin English, their lyrics were understandable for most West African populations. Kru music is said to have given birth to Palmwine Music, which in turn inspired several West African genres, including Sierra Leone’s Maringa, Nigeria’s Jujú, and Ghana’s Highlife. Researchers call this “musical confluence”, when old and new elements of music merge to create a new interethnic experience. This is a fascinating process and a beautiful, yet indirect, result of the movement of people.

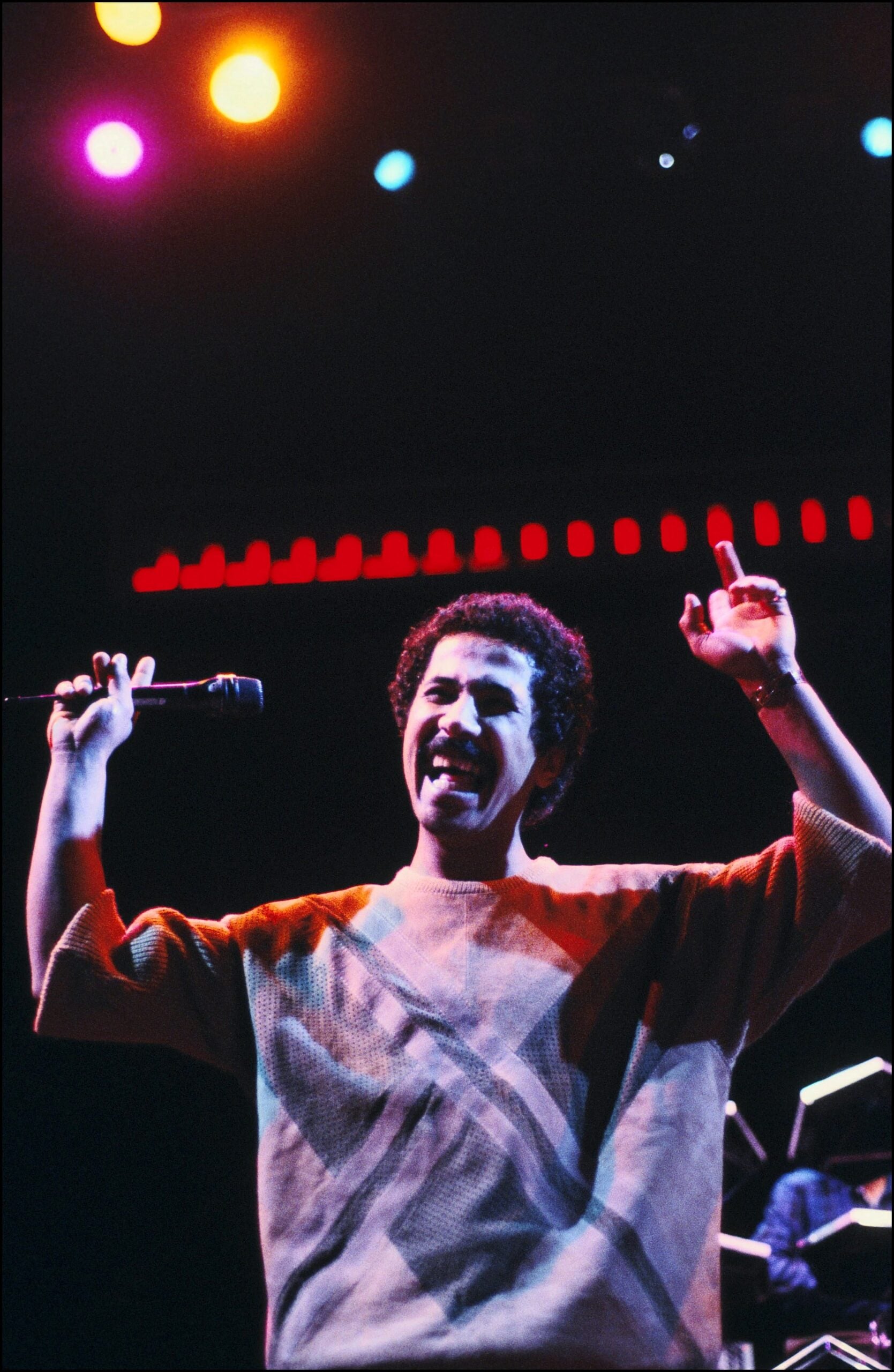

Over the last few months, I’ve been immersed in Cheb Mami’s discography, from his mid-80s recordings, all the way up to his early 2000s releases. This tea-candle-Mami ritual led to a profound discovery of the universe of Raï music and the artists behind it. After listening to all the Chebs and Chebas across different eras, one theme stands out: the layers in the sound and the yearning in the writing. In its early days, Raï was a form of Algerian folk music, built on vocals, flute, and percussion—sounds deeply embedded in local culture. Icons such as Cheikha Rimitti are a major reference for how Raï was performed in its early days. Rimitti belonged to a generation that treated music as a cultural practice, heard commonly at weddings, celebrations, and rituals. In 1978, she moved to France, forced to leave by increasing restrictions from local authorities—a fate shared by many Algerian youth pursuing dreams across the Mediterranean. This raises a compelling question: what happens when the musician becomes an immigrant?

As soon as the 1980s arrived, Raï began evolving with contemporary instruments and sounds, but its core remained unchanged: stories of life, love, sorrow, and the longing for home across the sea. Born in Oran, a city in northwestern Algeria known for its rich musical tradition and waves of migration, Raï produced artists like Cheb Khaled, Cheba Fadela, and Cheb Tati, as well as nearby icons such as Rachid Taha and Cheb Mami. This generation grew up familiar with the realities of immigration to Europe, navigating the hardships of life in the far north, feeling the ache of distance while thriving creatively. When Algerian music crossed into France, it gave rise to a new Raï sound that reflected the interplay of place and generation. It became funkier and more multilingual, evident in Rimitti’s later music, particularly her all-time banger NOUAR, which expanded from pure folk to embrace piano, guitar, and synthesiser influences.

The experience of exile, estrangement, and longing for home emerged as a central theme, embraced even by Raï singers who never left Algeria. The genre’s evolution is inseparable from the immigrant experience, shaped and amplified by its growing popularity across France and beyond. Unlike other ‘80s pop music, Raï uniquely captured migration as a theme. If the decade was defined by “Sex, Drugs, and Rock ’n’ Roll” for the West, for North Africans it was “Exile, Belonging, and Raï.”

Not all migrants make music the same way. One can distinguish between first, second, and third-generation immigrants. While it’s arguable that immigrant children are in a strong position to fuse sounds and instruments, it takes a large wave of first-generation migrants, roughly a decade of adjusting to a new land, and a socio-economic turning point to produce a sound that is both culturally rooted and sonically daring. A case in point is the second wave of Raï, where the music evolved from folk to pop-synth.

When examining immigration data, particularly for the Algeria-France corridor, it is notable that migration stock can be traced back to 1912. However, the largest increase occurred between 1970 and 1990, a period following independence and the advent of family reunification. Imagine the flow of emotions: independence, liberation, yet you still seek to migrate to what was once your coloniser. You are free, but barely. It must feel strange and alienating. It’s no surprise, then, that the ‘80s and ‘90s produced a wealth of music lyrically steeped in themes of home and ghorba (estrangement).

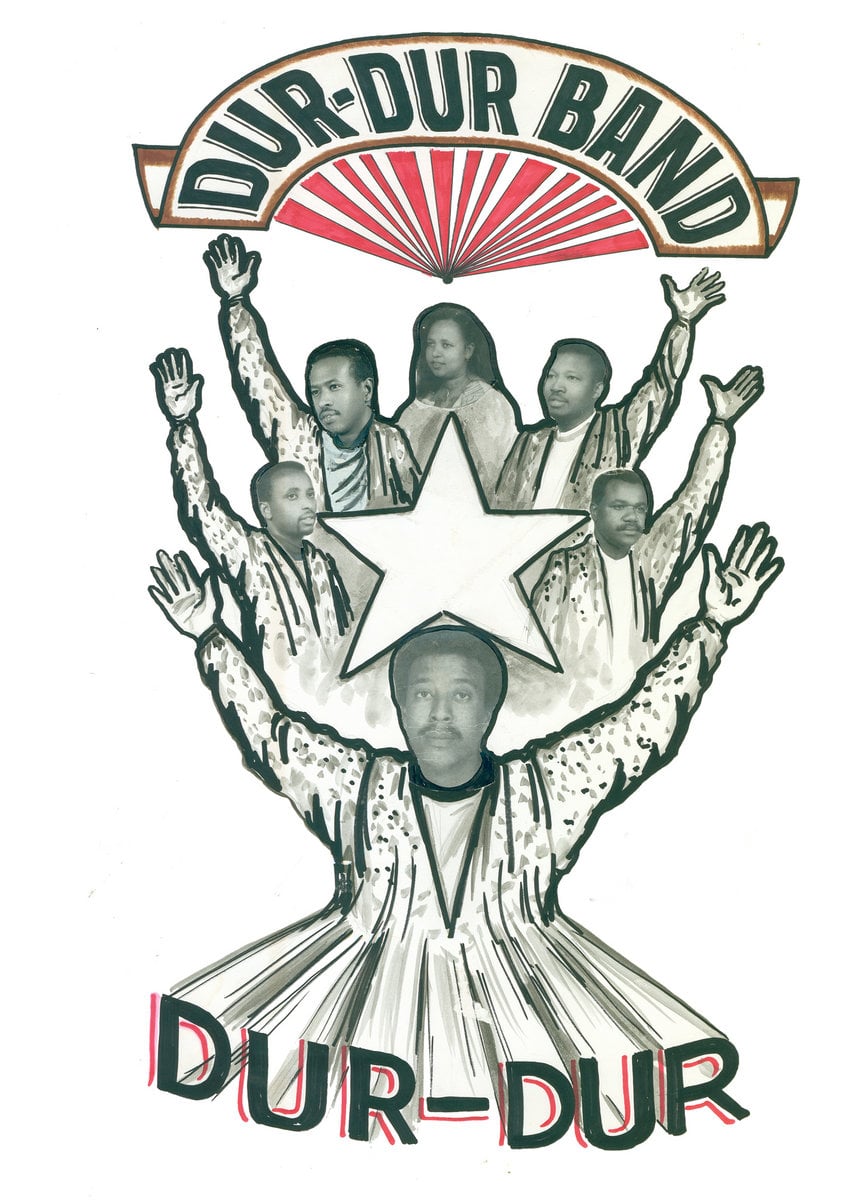

A similar trend appears with the re-emergence of Somali funk music, which reached its peak in the ‘80s, post-British independence, during what is often called the “Golden Era.” At the time, the music resembled a heavy baseline of funk and psychedelic rock sounds, birthing a Moga-disco out of Mogadishu. Little is known about Somali music after the civil war erupted in 1991, followed by a long-lasting wave of religious radicalisation. Between 1990 and 2015, roughly 2 million Somali-born individuals moved abroad. The UK, the primary destination, saw thousands arrive between 1991 and 2001. A decade later, Dur Dur, one of Somalia’s most iconic bands, reformed in the UK with original members and artists from other Somali bands, producing a sound that was deeply resonant, culturally rooted, and sonically daring—bringing listeners back to the Moga-disco era. This revival was shaped by a large wave of first-generation immigrants, a decade (or more) of adapting to new lands, and the backdrop of political turmoil.

Ten years on from Europe’s migration influx, with millions displaced and socio-economic shifts reshaping communities, is a new music emerging? One that is deeply resonant, culturally rooted, and sonically daring?

Writing this piece from Berlin, the answer is all around. Berlin has drawn large numbers of immigrants from across the region, making it an exemplary case study. The city’s creative pull has always been strong, particularly for artists and musicians, due to lower living costs compared to other European capitals, and some imagined freedom of expression. Communities built on shared experiences and interests have formed deep layers within the city’s underground scene, celebrating and creating sounds unfamiliar to the cultural mainstream.

When you go around the Arab functions in the city, one sound always strikes: Shamstep—a fusion of Levantine Dabke with electronic music, creating something loud and bold. The sound was pioneered by a Palestinian-Jordanian collective called 47Soul, who launched the genre in 2013, a time of hope and newness in the region, just before waves of displacement carried people from their homes to the West and beyond. Over the years, Shamstep has grown stronger and more popular, celebrated for its raw edge and cultural resonance. Stars like Omar Souleyman and his music have become a desired sound, found frequently touring on an international jet, cultivating millions of fans.

Today’s social media, virality, and migrant movement have unlocked a new level of cross-cultural collaboration, fueling a wave of music shaped by the diaspora. One standout figure is Saint Levant, a trilingual Gen Z artist who initially leaned into pop and R&B but is increasingly weaving in the cultural DNA of his two homelands, Palestine and Algeria. His songs may touch on late-night Parisian romances, but layered within are themes of exile, occupation, and resistance. These influences surface initially in tracks like “Qalbi” and expand through collaborations with regional artists in tracks such as “Samra” (with Babylone) and “DALOONA” featuring 47Soul, Shadi Borini, and Qassem Al-Najjar, all enriching his sound with cultural depth and resonance.

However, it’s still not easy to spot a sonically daring sound with deep cultural and emotional roots. Perhaps the emergence of a new sound requires more than just a digital process. After all, low entry barriers tend to favour quantity over quality. Maybe a more analogue approach is needed. Against this backdrop, immigrants will inevitably attempt to reconnect musically with their roots and heritage, creating space for the revival of instruments that previous generations cherished. Look at us and our friends, digging through old records in crates or on YouTube. The quest for tapes is intentional, a search for a different sound and a familiar connection. Many of us are soaking in culture through listening experiences, discovering new music that is, in fact, old.

Electronic elements dominate much of today’s Arab music scene, yet they remain playfully intertwined with local folk music, a natural outcome of movement and migration. It’s easy to predict this fusion will continue into the near future: electronica meets folk, blended into something new. It would be exciting to see the emergence of a tropical and Balearic synth-pop ‘80s sound, think Arabic flute and lyrics about the sea, love and palm trees, or a dub-infused sound with Egyptian percussion and Qanun.

It could come from anywhere. It could go anywhere. A new sound must be travelled. A new sound must be felt. Do we love it or hate it? Either way, it moves effortlessly across borders and barriers, carrying both memory and reinvention.