News

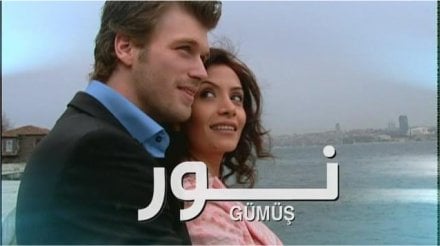

On August 30, 2008, 85 million Arab viewers were cooped up in their homes, their eyes glued to their TVs. Not to watch a politician’s speech or a news broadcast, but to tune in to the series finale of the mega-successful Arabic-dubbed Turkish soap opera Gümüs. While most fans of the show don’t know the original Turkish title, they are familiar with the Arabic one: Noor.

There was once a time when Arabic dubbed content was almost inescapable across the Arab world. Pre-streaming era, popular broadcast TV shows and movies were the main topics of everyday conversations. Streets would be empty during prime time, as people were tuned in to their TVs, preparing for the conversation they would have with neighbours and friends over coffee the next morning.

Simply defined, dubbing is a form of audiovisual translation that involves replacing the original track of a film’s dialogue in its source language with another track where these dialogues have been recorded in another language, the lines adapted to match with the lip movements of the actors on-screen.

By nature, dubbing is a process of cultural negotiation. After all, how do you import a foreign cultural product, overlay it with the Arabic language, and expect Arab audiences to relate to the protagonists and plot lines without anticipating any cultural friction? And what Arabic dialect out of the roughly 25 Arabic dialects should the content be dubbed into? Add to that the strict censorship laws that forced dubbing companies to navigate strict restrictions and complex cultural considerations. The result was a constant process of trial and error that forced dubbing companies to constantly learn, apply, and adapt.

In speaking to renowned Arab media scholar Ramez Maluf, the late Nicolas Abou Samah, founder of the prominent Lebanese dubbing studio Filmali, effectively captures the crux of this cultural dilemma in a few words, describing why dubbed Hollywood productions specifically do not translate well for Arab audiences: “Arab heroes do not use curse words. They don’t jump on a moving train, slide down a window and machine gun 10 criminals.”

Egypt was the first Arab country to experiment with dubbing for cinema in the mid-1940s with films like the American comedy Mr. Deeds Goes to Town; however, these early dubs were not popular among Egyptian audiences. The dubbing industry would then find new life in Lebanon decades later in the 1970s, when Filmali started dubbing Soviet and Polish war movies into Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), the standardised literary form of Arabic common across Arab countries known as Fus’ha. Unsurprisingly, these dubs were not so popular either.

Cultural nuances aside, dubbing is a costly and complicated process, requiring large teams of people working around the clock. This is paired with the fact that the region lacks the proper professional talent for dubbing work, which is attributed to the presence of only a handful of institutions in Arab countries that offer training in audiovisual translation, like the American University in Cairo, Balamand University in Lebanon, and Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar.

All these factors explain why subtitled content remains more popular than dubbed content across Arabophone countries today. When dubbing requires that audiences identify with the characters on-screen and accept the plotlines as part of their cultural environment because of the overlaid Arabic dialogue track, subtitles visually and thematically reinforce the fact that the moving images are foreign to the local culture.

But it is within the push and pull of cultures, and the negotiation and adaptation processes involved in dubbing foreign TV productions and feature films, that some types of dubbed content have stood out to Arab audiences over the years. Children’s cartoons, Mexican telenovelas, and Turkish soap operas are interesting case studies that are instantly familiar to the everyday Arab.

ANIME

Cartoons were among the first segments of programming to be dubbed into Arabic, mostly to facilitate their reception by children who would otherwise not be able to keep up with subtitles. Anime (Japanese animation) was imported into the region in the 1970s, as broadcast TV stations were proliferating in the Gulf and creating a demand for broadcast entertainment programming, especially for the youth. So, the GCC Joint Program Production Institution was founded in Kuwait in 1976 to push programming on a pan-Arab scale.

With an underdeveloped and underfunded but fast-growing entertainment sector, providing children’s programming quickly required the institution to look at the most prolific entertainment industries to see what worked, and Japan stood out as a culturally fit market to import from at a low cost.

Anime cartoons were mostly dubbed into MSA, mainly for two reasons. The first is that it’s the form of Arabic formally taught in schools and could be understood by children audiences around the region. The second is that the themes of social responsibility, familial duties, honour, commitment, and solidarity, resonated deeply with the cultural and national ethos of the flourishing Gulf nations.

Anime’s impact on today’s Arab millennials cannot be underscored enough – most Arabs who grew up in the region in the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s, can recall tuning in to channels like Spacetoon and MBC3 to watch the likes of Pokémon, Dragon Ball, and other shows that captivated and inspired young audiences, breeding a generation of anime enthusiasts. One factor often credited for this impact is, in fact, the impeccable voice acting in these shows’ Arabic dubs.

“The Arab voice actors delivered like they were acting, not just dubbing. The dubbing was done so realistically and so expertly that it spoke to both adults and children. The Arabic dubbing teams did a fantastic job, as if acting out the characters we saw on the screen. The feelings were very real and raw, which is why we still love these dubbed works to this day,” says Saudi anime enthusiast Jarrah Alfurih, whose credentials include being the founder of an encyclopedia dedicated to the Iron Man, the half-green half-red bodysuit donning giant robot protagonist of the campy anime Dinosaur War Izenborg.

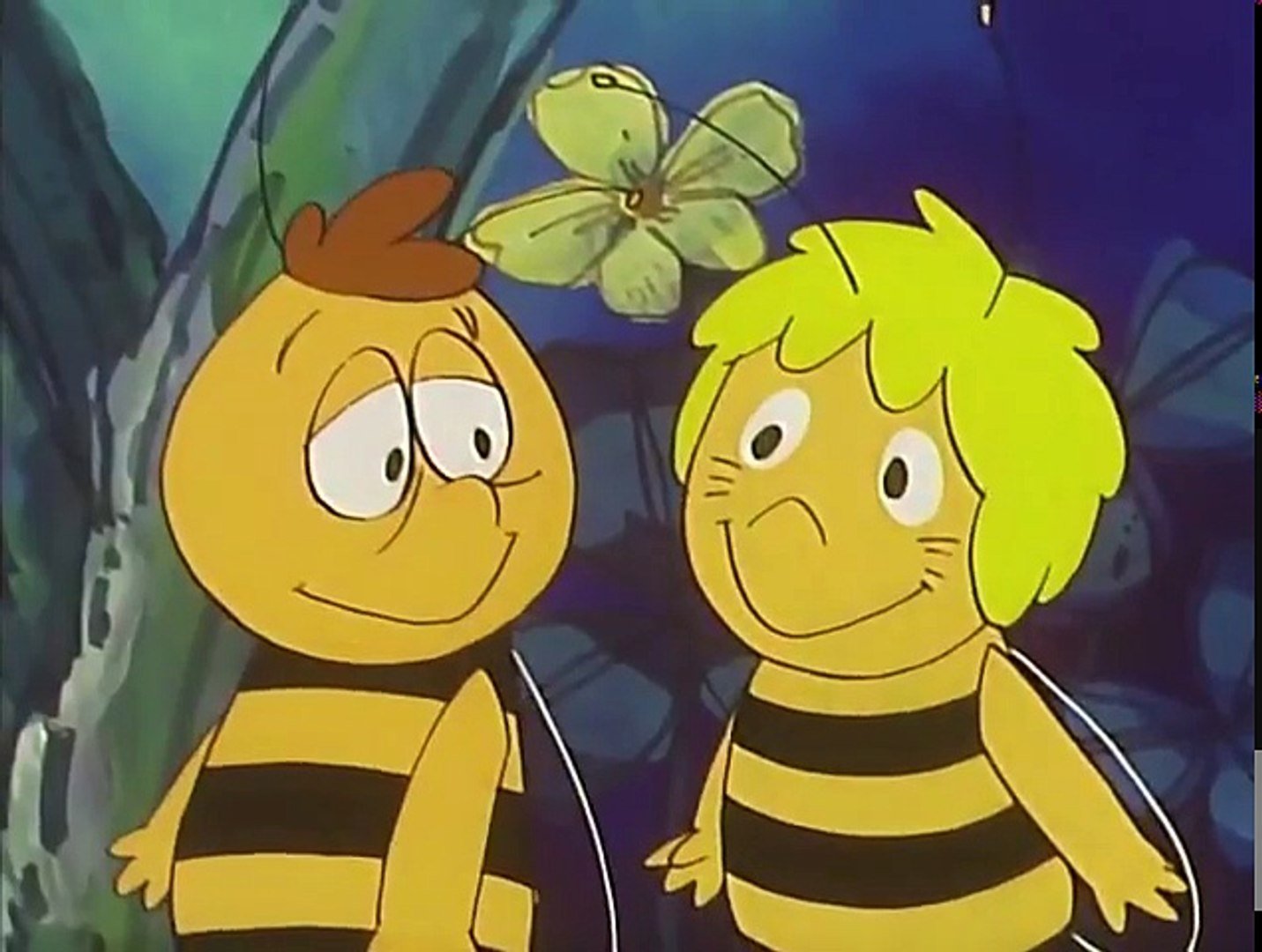

In that respect, the success of anime in the region could hugely be credited to the quality work of the aforementioned Filmali, which worked on dubbing the hugely successful Arabian Naito: Shinbaddo no bôken (Sindibad), paving the way for more Arabic dubs of titles like Mitsubachi Maya no bôken (Zeina Wa Nahoul), and the iconic Yūfō Robo Gurendaizā (Grendizer). The impact of these dubs on fans is potent to this day, the Grendizer theme song being an endearing example. The translated theme was memorably sung by the late Lebanese singer Sammy Clark, who performed the beloved tune at the 2019 Saudi Anime Expo to hundreds of wide-eyed fans. A quick YouTube search reveals the millions of views that his performances of the theme song have received. It’s essential nostalgia for the Arab Spacetoon generation.

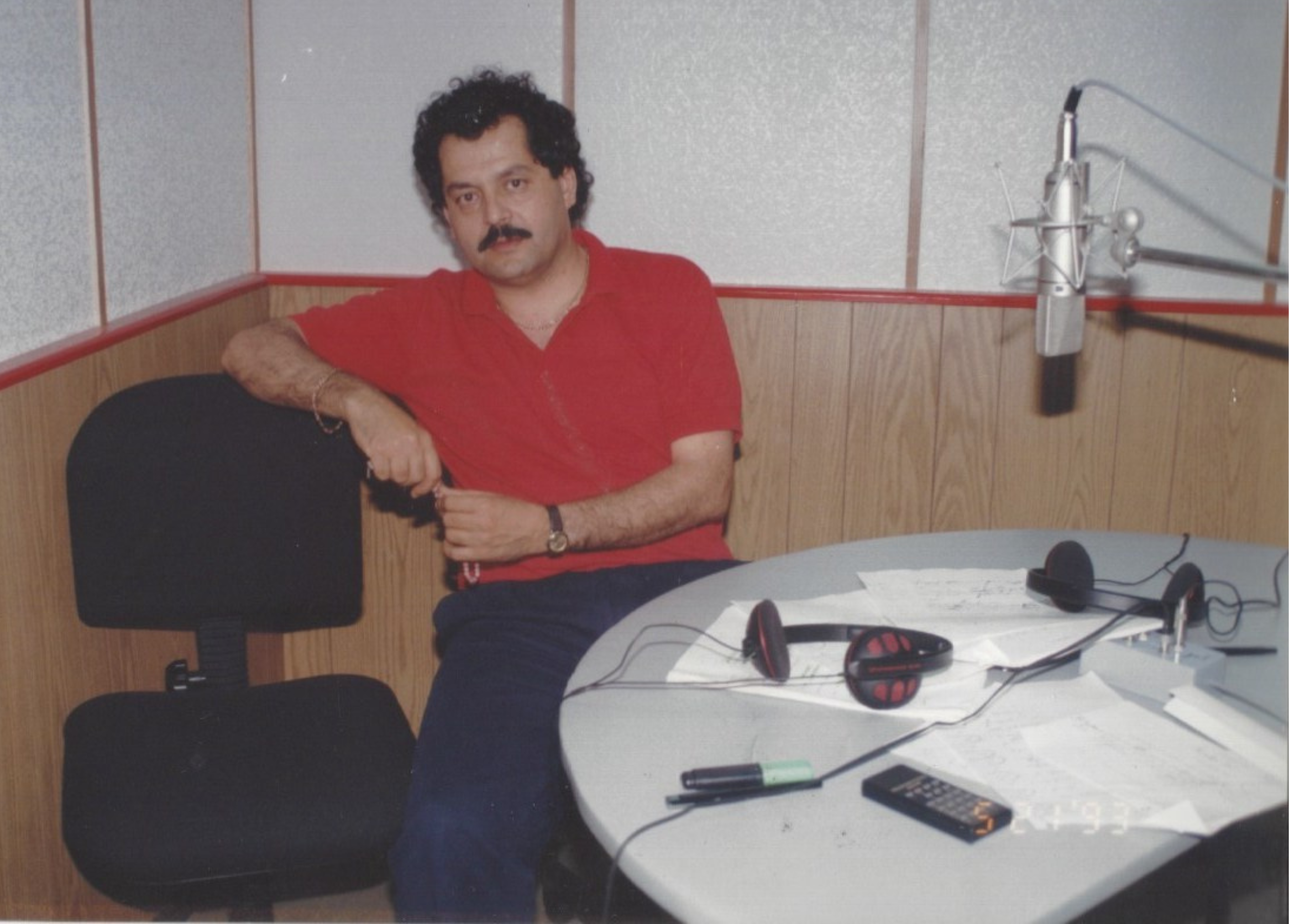

Speaking to ICON, Wissam Badine, who took over the Filmali family business through his kinship to Abu Samah and then rebranded it to today’s DeafCat Studios, recalls his childhood memories to describe how the buzzing studios operated way back then. “[The period between the ’70s and ’90s] was the golden era of dubbed animated content… Most of the important voice actors that you know today had worked with Filmali at some point. There was a lot of trial and error in the beginning and the equipment back then was very expensive. We had producers, translators, mixers, actors – it was a big company and they were all employed [full-time]. There was a huge number of staff to get work done efficiently and at volume,” he explains.

The success of anime inspired a sea of dubbed children’s cartoons, most notably Disney cartoons, following the establishment of Disney Channel Middle East in 1997. And while Filmali was responsible for a lot of the associated dubbing work, the choice to stick to MSA as the default choice for dubbing was now being put into question, as opting for an approach that incorporated a more colloquial and spoken form of Arabic to make the cartoons more approachable seemed more reasonable.

In 2023, Aysha Selim, who served as Disney Character Voices International’s Creative and Operational Manager for Arabic Dubbing from 1997 to 2006, spoke to the online Arab animation platform mt7rk, describing in detail the years-spanning learning process that her team underwent while doing the localisation work for Disney.

At first, there was a decision to dub all of Disney’s standard characters into MSA so that they could speak to everyone in the region. For the series, however, and more specifically anything comedy, her team leaned into the Egyptian dialect, which sounded more familiar to Arab audiences because of the popularity of Egyptian programming at the time, and easily lended itself to humour. However, after a long series of experimentations with different dialects, including the Lebanese one, the executives at Disney quickly realised that MSA would be the way to go, mostly to create a more unified approach to the dubbing process and appease all involved parties involved in distributing the content. The outcry from fans on social media, however, proved that Disney’s gut feeling of opting for a “lighter” dialect was justified. But, up until today, most Disney content continues to be dubbed into MSA, with some modifications slipped in.

The case about dialect being the make-or-break factor behind the success of Arabic dubbed content, while largely backed up by proof, is easily challenged by one genre in particular…

MEXICAN TELENOVELAS

These telenovelas landed in the Arab region seemingly by chance. “In the 1990s, [Abu Samah] came across a particular Mexican telenovela. He was at Cannes, and by coincidence, he found a box that had [recorded tapes] of a telenovela inside. So, he brought them back with him and dubbed them into Arabic. That show ended up being a big hit,” Badine remembers.

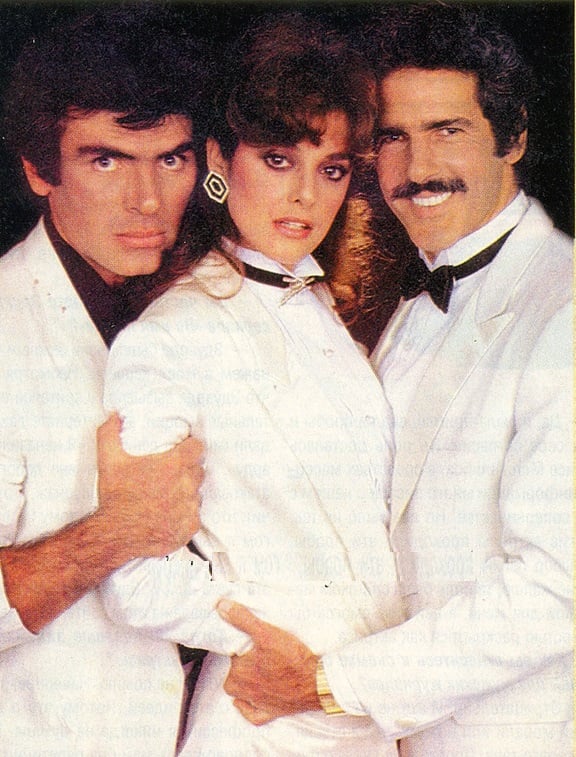

The show he is talking about is none other than the groundbreaking hit Tú o Nadie (Anta Aw La Ahad), which took the Middle East, and specifically post-civil war Lebanon, by storm upon airing in 1992, inspiring a generation of parents to name their children Antonio and Raquel after the show’s starry-eyed protagonists. The unexpected success of the show inspired 11 more Mexican and Brazilian telenovelas to be dubbed into MSA over the next eight years, bringing in stacks of money for stations like the Lebanese Broadcast Corporation (LBC), and at a significantly low cost compared to local productions.

The genre’s legacy in the region lives on, as Arab audiences look back at those telenovelas with admiration and heart-wrenching nostalgia. A quick scroll through the YouTube comments under a video of Anta Aw La Ahad’s Arabic theme song, which has garnered almost 1,000,000 views, is immediate proof. But, nostalgia aside, one of the most prominent aspects of these shows that continues to be remembered is the dubbing. Not necessarily in a positive light.

When these shows dealt with everyday discourse and dramatic themes of love, loss, betrayal, and loyalty, the choice to dub them into MSA, which was reserved for literature, formal occasions, and news broadcasts, was jarring for many. Simply put, the real-life issues tackled in these programs were reserved for informal and more casual everyday Arabic. If the objective of a good dub was to make audiences forget that they were viewing a translated production, these dubs did the exact opposite. This incongruity between the subject matter and the language used to communicate it has made these dubbed telenovelas the butt of many popular jokes, inspiring countless sketches on comedy shows like the Lebanese SL Chi, which poked fun at the exaggerated accents, unsynchronised lip movements, and absurd plot lines.

Unlike the dubbed content that came before it, the success of these shows was not necessarily tied to the quality of the dubbing, but rather the cultural gap they filled in the programming at the time, providing elements that weren’t present in local productions and an endless world of escapism. They often depicted luxurious lifestyles, extravagant homes, tolerant social environments, freedom when it came to love and marriage, and a general openness that audiences indulged in as things that simply “did not happen in real life.” Adding to that, one definitive factor in this genre’s success is the partial cultural proximity between Arab and Mexican cultures. While Arab audiences did not fully identify with the racy plotlines of these telenovelas, it was not unthinkable to believe that similar events and stories were not taking place next door. These shows required minimal editing to make them acceptable to an Arab audience without jeopardising their plotlines. The cultural leap was minimal for the audience, and cost-effective for broadcasters.

According to Badine, these shows were also easy to consume, which added to their success. “[This is a generalisation], but people prefer to be as passive as possible while watching TV. Kids don’t know how to read, so you need to dub their content. But, with soap operas, viewers are mostly housewives and older women and men. They’re either cooking or doing things around the house while watching, so they prefer to consume dubbed content,” he explains.

Telenovelas like Anta Aw La Ahad expanded Arab audiences’ palates when it came to foreign content, paving the way for other forms of popular dubbed programming coming from faraway countries like India and Korea. But one genre would stand out in particular, forever changing the way broadcasters perceived the power of dubbing.

TURKISH SERIES

Turkish soap operas dominated Arab television for years starting in the mid-2000s. This could easily be attributed to Noor, which sent waves across the Middle East. According to reports, three to four million people out of Saudi Arabia’s population of 28 million would tune in daily. In Palestine, streets would be deserted during showtime. Posters of Noor and Mohannad, the show’s trouble-making protagonists, were being sold alongside imagery of Yasser Arafat and Saddam Hussein. Mohannad, played by Turkish star Kıvanç Tatlıtuğ, was a particularly problematic facet of the Noor phenomenon, sparking romantic tensions between wives and their husbands. When the men wanted to look like him, the women wished they would act more like him. Many divorce files followed.

In several ways, Noor caused a media revolution, changing the way broadcasters like MBC, which imported the show, dealt with dubbed foreign productions. The show’s disruptive success is attributed to an amalgamation of all the components that made the dubbed content before it so appealing.

MBC took a successful gamble with Noor, dubbing the show into the Syrian dialect via Sama production studios in Damascus. This decision, while seemingly arbitrary, was a direct reaction to the years-spanning practice of dubbing foreign productions into MSA, which was causing a disconnect with viewers. Turkey also shares a border with Syria, a geographic and cultural proximity that broadcasters wanted to bank on. That and the fact that hiring Syrian voice actors was cheaper than the more popular Egyptian voice actors. So, for once, watching a dubbed show felt less like being in Arabic literature class and more like watching entertainment.

Turkish soap operas were not only dubbed but also adapted very well, the censorship process actually playing a role in facilitating their success among Arab audiences. The themes of marriage and family reinforced a lot of Arab social values, but by virtue of still being foreign, the shows had leeway to depict taboo subjects in a more familiar context for audiences compared to Mexican telenovelas. A lot of the censorship involved in localising the shows had to do with love scenes or other scenes which depicted substance abuse or sexually sensitive material. However, despite the censorship, Noor still caused moral panic, receiving considerable backlash from religious establishments across the region, and adding to the already existing anxieties among scholars and politicians about the “assaults” on Arab identity imposed by the genre and other foreign programming. This push and pull resulted in a recipe for unprecedented success, cementing Turkish series as a staple in the region’s programming, and the Syrian dialect as the most fitting for this kind of entertainment content.

Dubbing in the Arab world is an understudied field, its impact on Arab audiences remains unexamined for the most part. Broadcasters have experimented with the Moroccan dialect, Lebanese dialect, and many more, but to delve into the complexities and history of the practice in the region, which is hugely influenced by regional politics and cultural flows, would be the undertaking of an Arab media scholar writing a book.

There’s one obvious conclusion, however. The results of broadcasters’ years of seeing what simply “worked” to varying levels of success have manifested clearly in Arab pop culture and media. Turkish series are still popular today, and many of them are still being dubbed into the Syrian dialect. In fact, with the advent of streaming and rise of regional streaming platforms like STARZPLAY, viewers now have the option to watch some of their favourite series in a number of dialects. Other genres have flourished over the last few years as well, specifically Hindi dramas and K-dramas. And those same challenges that broadcasters faced in the early days of television are still very much present, with MSA still looming over most dubbed content. However, it looks like there’s a dubbing revolution on the horizon, and artificial intelligence (AI) is largely to thank.

“[At DeafCat Studios we keep Filmali’s] legacy alive through the things we learned from the company, the techniques… Pivoting with technology is crucial. Today dubbing is done in a specific way, five years down the line, with AI, this whole industry is going to be badly disrupted. We’re being extremely challenged to adapt to this new AI reality, and now the challenge is to rebuild a team that can understand and operate AI and make the best use out of it to see how we can adapt,” explains Badine.

The bad news for dubbing studios is good news for viewers. With AI, dubs could be made quicker, at more volume, and with a much greater variety of dialects to cater to every single country and market. But until then, Arab audiences will have to stick to hearing their favourite Turkish actors speak in Syrian Arabic or worst case, their favourite Korean actors speak Fus’ha.

Words: Hadi Afif