Everything

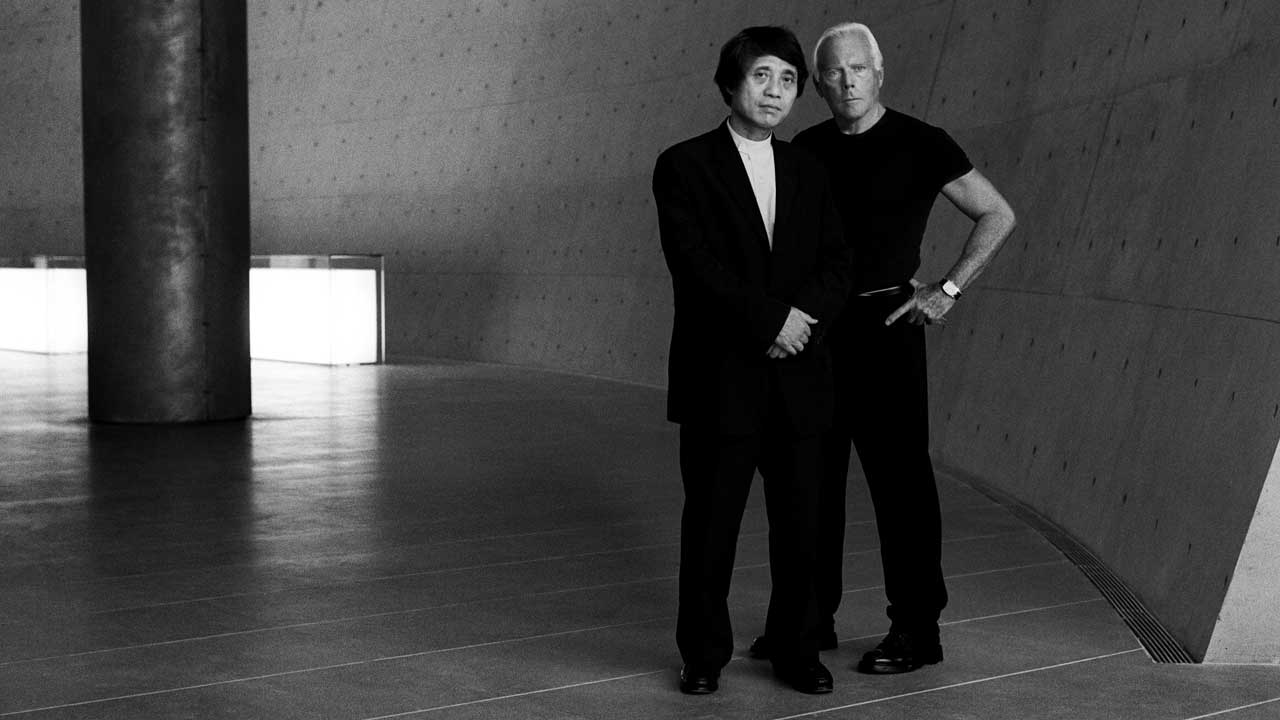

“In Tadao Ando’s architecture, I see an extraordinary ability to transform ‘heavy’ materials such as metal and concrete into something truly exciting. I very much like his use of light, a fundamental element that helps shape the character of spaces” – Giorgio Armani

I had the pleasure of experiencing Tadao Ando speak at the Art Institute of Chicago some years ago. He spoke not a word of English, but his presence and philosophy transcended the translator between us. His status rivals that of architects Zaha Hadid, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, the man who sparked his initial interest in architecture when he was in his early 20s. Ando’s touch-and-go existence between modernism and postmodernism is known as ‘critical regionalism’, reflecting the culture of a region through its design and materials where aesthetic ornamentation is only applied in a meaningful way.

By balancing aspects of modernism with Japanese principals of design, Ando has been able to carve an impressive name for himself in the architecture world and has received many awards throughout his career, such as the Pritzker Prize for architecture in 1995, considered the highest accolade in the eld. Since setting up shop in 1969, Ando has designed more than 200 buildings. Indeed his philosophy and extreme precision inspired Giorgio Armani to commission him to design the Armani Theatre (Teatro Armani) in Milan, in 2001 – the first example of recycled architecture in Milan. “Much was discarded in the postwar Japanese houses in the name of rationalism: contact with nature, the tangible aspects of life, the rays of the sun, the flow of the wind, and the sound of the rain,” Ando once shared with Australian design website Habitus Living. “But I did not wish to discard the elements that directly speak to the body and spirit.”

Ando’s desire to help people reflect on their inner selves rather than focus on the outward visual is just one example of how the Japanese philosophy of Zen manifests itself in his work. He is continually striving to create and surpass what has already been created: “In museums you never have pillars to interfere with your site,” he says. “If I can create some space that people haven’t experienced before, and if it stays with them or gives them a dream for the future, that’s the kind of structure I seek to create.”

The architect is a guide, creating strategic pathways through his buildings that allow its visitor to consider the shapes and forms without distraction. His meticulous use of space and his emphasis on the physical experience of architecture is a large part of his notoriety for visual simplicity and sensitivity to the surrounding environment.

For Ando, architecture is at its best when it allows people to experience the beauty of nature. “Architecture is not a self-independent individuality. In my opinion, it comes to existence only through relation to various elements of the surroundings like water, green, light or wind,” he says. This continuity of indoor and outdoor space is a principle typical of Japanese culture and Ando innovates this philosophy by incorporating a modernist touch. Exhibited at the Silos under the theme Landscape Genesis, his original work at the Makomanai Takino Cemetery in Sapporo framed a 44-foot-tall Buddha in a lavender hill. “The aim of this project was to build a prayer hall that would enhance the attractiveness of a stone Buddha sculpted 15 years ago. The site is a gently sloping hill on 180 hectares of lush land belonging to a cemetery,” Ando wrote for Domus magazine.

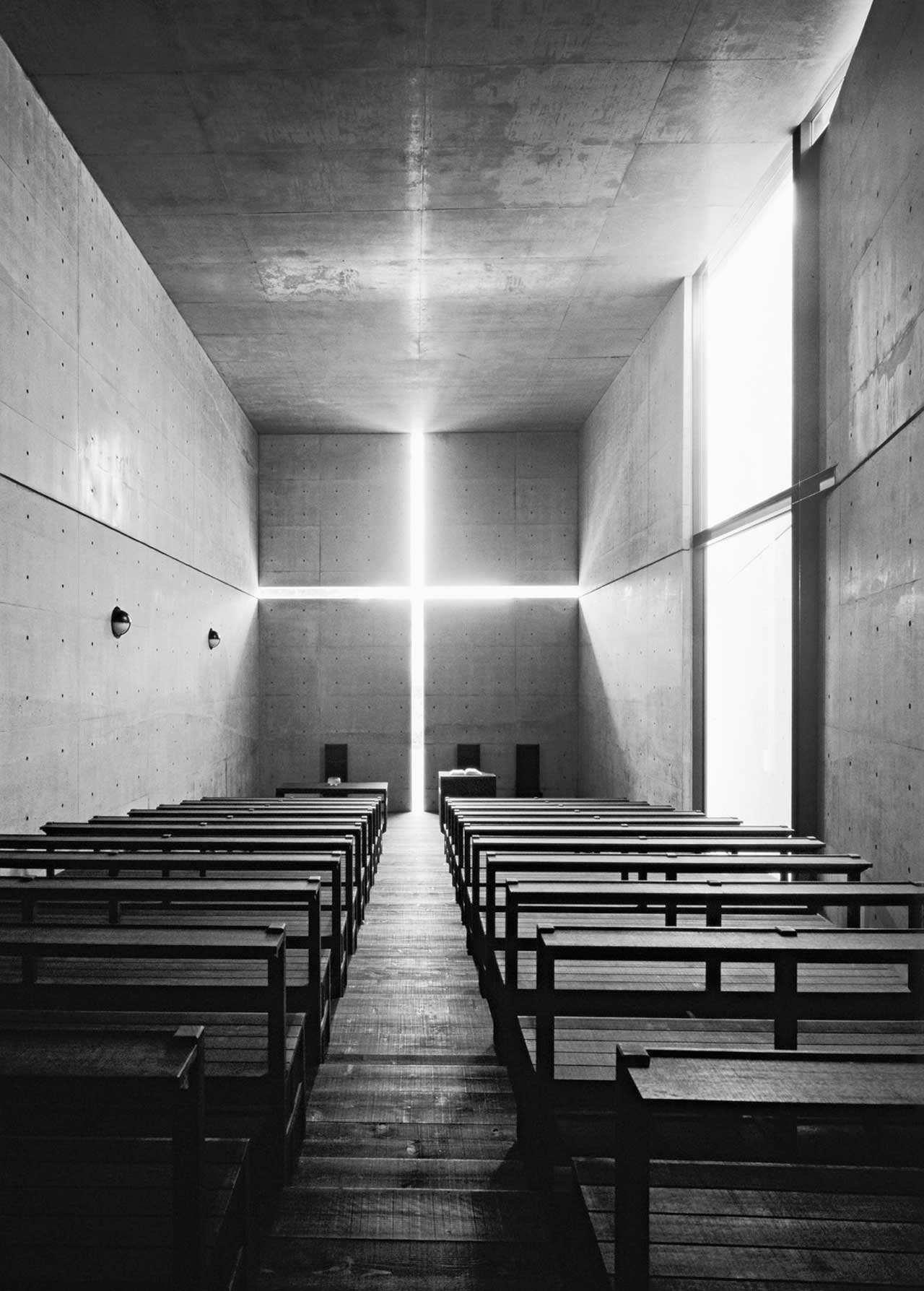

“I attribute the fact that nature is incorporated into my designs to the proximity of water and greenery to my childhood neighbourhood. My house was adjacent to the Yodogawa, the largest river in the Osaka region. These two elements, light

and nature, resided near me and led me to create buildings like Church of the Light [and] Church on the Water,” Tadao explains. The motif of the place of worship also reoccurs in Tadao’s work, taking from Shinto a devotional attitude toward experiential spaces.

His iconic Church of the Light, built in 1989 and located just outside Osaka, is a prime example of the power of simplicity and is exhibited at the Silos as one of the Primitive Shapes of Space. Composed of a cement box perforated by light coming through a spliced cruciform, it’s a work that Ando once said embodied the key principles of his architecture practice.

“I believe that the emotional power in architecture comes from how we introduce natural elements into the architectural space. Therefore, rather than making elaborate forms, I choose simple geometries to draw delicate yet dramatic plays of light and shadow in space.”

This guiding philosophy is ever present in Ando’s work and use of concrete. What distinguishes his use of this common material is the smooth, almost reflective finish he’s able to achieve. Combined with bare, minimalist walls, this allows him to bring focus to the form of the building, as this is what he believes brings emotional impact to architecture. Ando uses his own recipe of concrete – ‘Ando Concrete’ – explaining that it must be a perfect balance of steel bars, water, sand and aggregate. The bars are placed at an equal distance, hence the holes. And the mix shouldn’t be runny – it should be viscous. The characteristic concrete finish is achieved by varnishing the forms before pouring begins.

In keeping with each other’s minimalist aesthetic, Giorgio Armani will host Ando at Armani/Silos – the first exhibition dedicated to architecture, a redesigned version of the major retrospective that Centre Pompidou dedicated to Ando last year in Paris. This project exhibits some of the key characteristics of the self-taught architect’s work – namely the use of raw concrete, dramatic play of natural light and the interplay of interior and exterior spaces. ‘The Challenge’, which will be inaugurated on April 9, is born from a collaboration between Ando’s studio and Centre Pompidou, to create a narrative path embracing the most significant operas of the architect. In a variety of more than 50 works – including technical drawings, original blueprints, sketches, illustrations, notebooks and video installations – this collection expresses the challenge (in its own title) that has driven Ando’s whole career, of trying to create something that will last forever. Exploring Eastern and Western artistic languages, it will engage you in a storytelling evolved throughout four main themes: Primitive Shapes of Space, An Urban Challenge, Landscape Genesis

and Dialogues With History.

The Challenge will open to the public on April 9 and run until July 28, 2019, at Armani/Silos, via Bergognone 40, Milan. It will be inaugurated during Salone del Mobile (Milan Furniture Fair), with the participation of the architect.

THIS ARTICLE APPEARED ORIGINALLY IN THE APRIL 2019 EDITION OF ICON MAGAZINE.

SUBSCRIBE HERE TO RECEIVE TWO PRINT EDITIONS PER YEAR FOR $30AUD