News

![]()

A woman stares proudly and defiantly outward while two fish whimsically circle her like two giant braids framing her head of bright orange-red hair. Wrapped around her neck with black thread is a human heart. The painting is by Iranian Paris-based artist Afarin Sajedi, and it is titled “Love” and dates to 2022.

The work, like others by Sajedi, is rife with metaphor and symbolism and acts like a delectable feast of ideas, statements and diverse cultures, merging her Iranian heritage with her present adopted home in Paris, France.

“Often my work has been characterised by where I have been born, but the figures I paint are from no particular culture,” she says. “They are individuals that could be from anywhere in the world.”

For Sajedi, the greater ideas on humanity, the complexities of life, love and freedom are more important than the cultural origins of her figures.

“I want everyone from around the world to be able to identify with the characters in my artwork,” she underlines.

Born in 1979 in Shiraz, Iran, the year of the Iranian Revolution, Sajedi grew up with a great love for art. As a child, her mother showed her paintings from the Italian Renaissance like those of the artists Raphael and artist Leonardi da Vinci.

“These works gave me an undeniable influence early on and it is for this reason that many of my paintings continue to incorporate stylistic references from the Italian Renaissance,” she explains.

When it came time to attend university, she went to Tehran to study at Tehran Azad University where she received her degree in graphic design. She has also worked as a graphic designer for around 10 years, creating designs for book covers, posters, illustrations for children’s books and animations. She’s also served as the director and cover designer of two Iranian lifestyle magazines, the comic strip illustrator for Negareh Tourism Magazine and an animation character designer for an Iranian children’s series. The stage and performance, a large influence on her artwork, is also a genre she herself has practised, taking theatre directing and acting courses at Karnameh Institute. She has also played the role of a lead actress in a telefilm.

Her evocative paintings retain remnants of her graphic design and theatre background—the colours and forms are vibrant and bold, pulling the viewer into her mystical and imaginative world. Inside are theatrical characters and performers with colourful faces like a clown, akin to Heinrich Boll’s clown and others often inspired by Japanese theatre and symbolism found in Western art, predominantly stemming from the Italian Renaissance. Each work is filled with metaphors, such as the fish, a recurrent symbol, as found in “Love,” which likens her works to aspects of surrealism or pop art.

Sajedi’s paintings probe the complexities of human nature, reflecting the delicate interplay between invitation and provocation. While her paintings easily mesmerise the spectator, they also catch the viewer off guard. Her figures appear regal, proud and otherworldly—the touch of defiance comes through provocation, through unexpected symbolism. An example can be found in “Ecce Homo” dated 2019 which depicts a Madonna and child, with Mary’s nose and cheeks blushed with red colour, again like a clown, another motif found in multiple works, while the child’s legs merge together to form a fishtail. A delicate golden halo can be found behind Mary’s head while her body is draped in a deep blue robe.

The clown face that appears greatly throughout her work is the result of much research she did on clowns during a period when she was undergoing great tragedy in her personal life.

“The red colour of the nose and the cheeks reflects a clown that has been crying,” she explains. To this day she depicts many of her portraits with the red nose and cheeks.

“I have a great passion for theatre and performance art, particularly the performers who don themselves with costumes and makeup,” she says. “It is another reason why the clown motif is so predominant in my work.”

![]()

Sajedi’s poignant and mesmerising works also reflect her Iranian heritage, exploring themes of identity and cross-cultural synthesis. While her paintings are laden with heightened expression and rich brushstrokes, her sculptures and installations often incorporate traditional Iranian motifs and materials a nod to richly coloured Persian miniature works, like the paintings of the Qajar dynasty.

Her work has been widely exhibited in galleries and museums around the world, including the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Additionally, Sajedi’s work has been shown at galleries in Tehran, London, Monaco and Rome.

One of her most remembered works, “The Unseen”, was a large-scale installation exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2017. The work comprised a series of suspended sculptures made from traditional Iranian ceramics and textiles. It represented the unseen and advocated a remembrance of Iranian culture and history—aspects that have been largely lost and forgotten under the current regime.

Through her art, Sajedi aims to recall the beauty and heritage of her Persian origins while merging it with inspiration from modern and contemporary art, the Baroque and the Italian Renaissance.

“The source of fear is behind the borders of invisibility,” she writes on her website. “It is what it is not…, the originator of imagination and very profound. How far can one go to search and restore it? Beyond the self? Beyond the frame of our bodies?”

“Fear,” she writes, “is a delight fused with terror. A maddening relative, isolated, and desolate. An ascension from being to galaxies of unsure and unknown risks that doubt breeds, to touching the vaguest and the darkest of them all. It is an encounter through which and from behind illusive glasses, we can observe how narrow the boundary is between the multiple blister cells of death and the glamour of precious stones.”

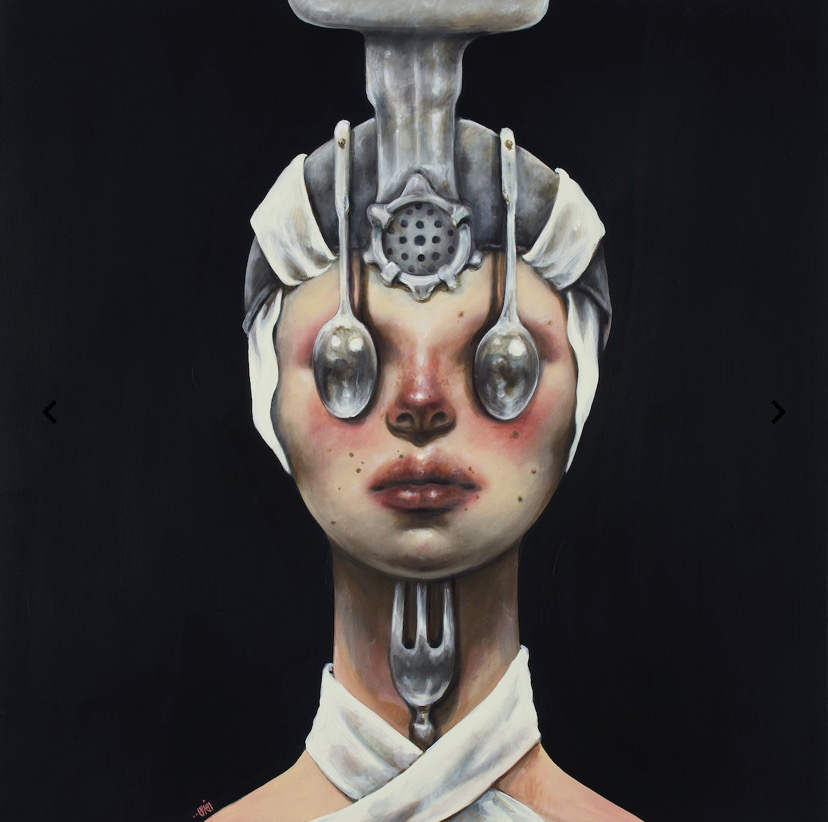

At the end of 2023, she exhibited her work at Dorothy Circus Gallery in Rome. Titled Bon Appétit, the show displayed a variety of her works on canvas depicting feasts of flowers, meat, fish, champagne and wine—details which served as powerful metaphors for the ephemerality of life.

In the exhibition, Sajedi reflected on the ritual act of dining and the symbolism found on the table to address the complexity of everyday life. Gripping portraits of women, one notable one depicts an elegant lady with dangling fish earrings biting her lip surrounded by wine bottles, roses and forks filled with food, surrounded by symbolism of food. The richly saturated colours common to the artist’s oeuvre reflect her pursuit of horror vacui or “fear of emptiness.” The vibrantly coloured portraits, with their heightened hues and details, echo works of the Italian Renaissance and the flamboyance and décor of the Rococo.

The protagonist in each work exhibited in Rome is a woman. Femininity and a woman’s place in the world have long been a focus of Sajedi’s work.

“I believe women and men are the same,” says Sajedi. “If I choose to paint women it is because I believe them to be more beautiful and their faces are more evocative to capture in a painting.”

However, she states that if she desires to paint a king, she will paint one but with the face of a woman. “I see the woman as a human, not specifically as different from a man,” she says. “Behind my portraits are not questions concerning feminism but rather explore the complexities of humanity—those that concern both men and women.”

![]()

In her 2019 exhibition “Ecce Mulier” at Dorothy Circus Gallery in London, Sajedi explored ideas behind contemporary women, heavily inspired by the writings of Goethe and Jung on their psychoanalytic analysis of the feminine.

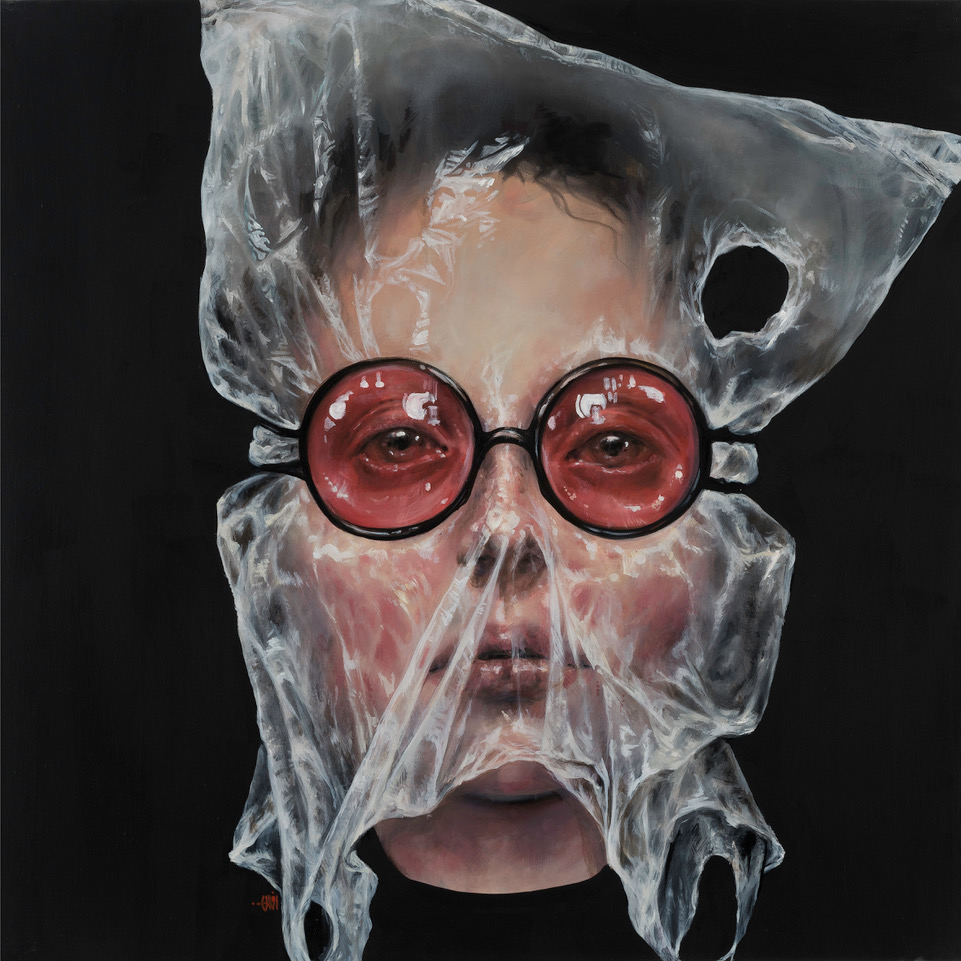

Yet the women in Sajedi’s works go even further. They appear to rebel. The women Sajedi portrays seem to occupy and resist their societal roles at the same time. Through a bold duel of expressive light and shadows, they dress in elegant, yet unconventional attire—unconventional often for the details Sajedi adorns them with—fish earrings, spoons over eyes and rosy clown noses.

In this manner, she celebrates their femininity and strength and encourages their individuality and freedom to follow their heart and live the life they desire. Her figures, as stated in the release of her Rome show, are likened to historical female icons like Marie Antoinette. The subtle parallel champions the pioneering spirit of visionary women of the 18th century, such as Antoinette, and gives them renewed vitality today for contemporary women, particularly for the women of Sajedi’s homeland of Iran.

However, Sajedi’s works are often discomforting to behold. The women in her portraits are beautiful but their unconventional renderings reflect the complex mix of emotions the modern Iranian woman feels. While a range of art historical influences are reflected in her work, Gustav Klimt’s colour palette might be seen to have influenced her use of the colour red and her intricate attention to detail.

Nods to the traditional hijab headwear so long obligatory for Iranian women and the reason for nationwide protests at the end of 2022 can be found in several works, notably in the way that the women’s garments are worn. References to the hijab can be found in the form of helmets or even plastic bags worn tightly around the wearer’s head like in “Vacuum” executed in 2014. In “Yellow Fight” painted in 2020 the woman’s hair is in the form of a bright pink anamorphous shape, unclear whether it is hair or a hat, while big circular sunglasses cover her eyes.

Regardless of their deformed and unconventional quality, Sajedi’s women are alluring and attractive. It is their strength and defiance that gives them beauty. They are, as the artist once called them, “a little bit of science fiction, a little bit of realism.” And that they are. Her women break free from the bounds of convention and yet elegantly still dwell within the confines of society. Through their heightened imaginative qualities, powerful emotion and boldness, Sajedi’s women evoke a rare sense of liberation as if through their mental prowess, their defiance and their zest for life, they have finally attained and earned their freedom.