News

When Donald Trump released an AI-generated video depicting his Gazan eutopia, one of the main talking points was the bearded belly-dancers on the beach, as though the concept of a blood resort paved over the cadavers of Palestinian martyrs wasn’t appalling enough. Today, Arab men are more politicised than ever. The West is insistent on containing us within their demonising or fetishising prism, erasing our diversity to make way for thin-layered prejudice instead. Arab men who challenge the masculine status quo are erased by their own societies, and used as leverage by the global north to depict the region as intolerant and inhumane, leaving them with little space to emancipate, free of tokenism and political dismemberment. Resultantly, Middle Eastern gender-nonconforming artists, who are lamentably presented with more opportunities to perform abroad than at home, are left bearing the burden of conditioned liberal Arab eyes relentlessly searching for any sign of orientalism or misrepresentation.

“The way the West perceives us is based on their limited understanding of our culture. They don’t understand that Raqis Sharqi is a practice that goes beyond what they see in their films. They took the aesthetics without considering the true meaning behind the language and the art form,” Khansa reluctantly muses. “I don’t dance Sharqi like Shakira. I’ve done my research and paid my dues. I teach oriental dance and have studied Tarab for years. As long as I’m being honest with the audience and meticulous with the art form, I’ve done enough.”

Ironically, Khansa’s artistic journey started at a very young age, as a means to escape the dire political climate he was born into. Raised a devout Muslim, he spent his first years of existence piously studying the Quran, in an environment devoid of art. “We’re not a creative household. I was always praying, attending ceremonies as a devout Shia boy, but also curious about the arts, music and dance. It felt good, it felt like an escape, like there was much more out there for me to discover.” Khansa is one of four sons, labelled by his relatives as the woustaneh, or “the middle child who’s always giving them a hard time”. One can only assume the impact such a moniker can have on a developing child. The description, however, did not deter him from continuing to explore what made him so different from his brothers. Soon enough, Khansa was choreographing school shows to the beats of Britney Spears and Madonna in front of a bewildered audience. “I remember trying to teach veiled girls how to be sexy on stage. It was absurd. Most of them ended up dropping out due to the nature of the performance. At some point, I had to gather my losses and perform alone to Madonna’s Die Another Day.” The song choice is almost prophetic considering the resilience he must have had throughout the years, in the face of so much resistance. While his fascination for performance art matured, so did the rift between him and his conservative peers. They were immersed in science and religion. He was engrossed by the glitz and glam, skipping school to gawk at Penelope Cruz’s musical number in Nine on the big screen, studying musical classics such as Kiss Me Kate, while listening to Umm Kulthum and watching Mexican soap operas. Khansa, however, was not your archetypal feminine boy. He dabbled in Taekwondo, was a very competitive athlete in school, though prancing at home and experimenting with makeup to his family’s dismay. “It’s rough to balance both. I struggled very early on to find my identity. I’m still figuring it out to this day, always trying to understand what I want to do, what I want to talk about. One thing’s for sure: I don’t want to be someone I’m not”, he says while gesturing with the undeniable grace of a highly trained dancer. Dressed in a white oversized All Saints crew neck and jorts, his demeanour is prosaically masculine, bar the fingernails painted in different shades of nude. “I am proud of what I have become, but am unable to confidently say that I am proud of the work.”

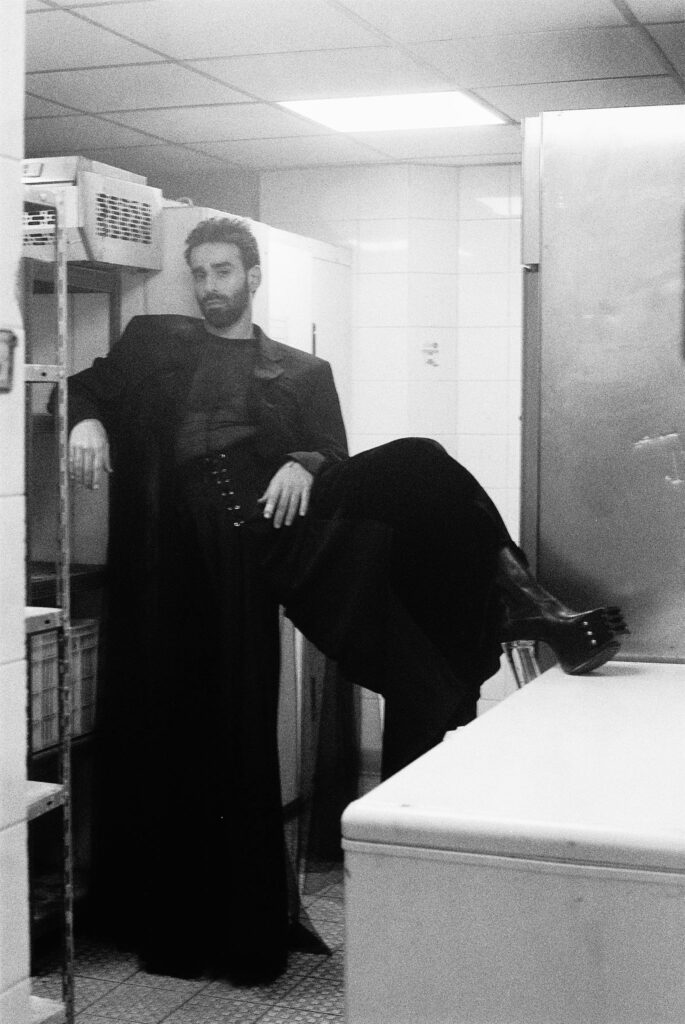

To hear the multi-hyphenated artist profess about his quest for self-actualisation comes as a surprise. Khansa has been a staple of the Lebanese artistic community, establishing himself as an aerialist, oriental dancer, singer, music producer and actor for years now. His performances are coveted for being spellbinding, raw, and evocative. Khansa has been gracing stages around the world with commandeering confidence, evoking his forerunners’ cultural legacy while expending his chiselled body as a storytelling vessel with a tint of eroticism. “Performance is not a career for me, it’s a lifestyle. It’s about cohesively crafting my multiple talents to achieve artistic perfection. It’s the spirit of Tarab. Tarab is a state of mind, it’s not just a genre of music. It’s about perfecting your practice by really pushing yourself beyond your limit. It’s very spiritual. It’s an energy that you want to master.” Indeed, his performances seem like witnessing a ritual unfolding live, as he contorts his virile musculature with the grace of a Mukhannath, while delivering melancholic vocals. His lyrics conjure the plight of a lovelorn romantic with a perpetual thirst to be acknowledged and treasured, while his choreography homages his cultural inheritance.

Watching Khansa perform is like witnessing over-exertion turn into complete liberation. While he depletes himself with every hip thrust, he selflessly elevates the energy in the room.

“It’s not about the performance itself but rather how it makes people feel. My Oriental teacher used to always say: ‘Do not feel the emotions, project them.’ Great artists know how to trigger emotions in others.”

Such is his plight: accumulating accolades and praise from audiences worldwide, while losing himself in the process. “I love what I do, but I struggle with confidence. I have insecurities. I’m always scared. I’ve been affected by what people think my entire life,” he confesses. “People think it’s easy to perform the way I do, but it’s not, especially in this society.”

We often assume that once an artist reaches a certain level of success or notoriety, their inner demons dissipate. According to Khansa, that couldn’t be further from the truth. “When I step onstage, I build a wall for the audience to be able to take control and captivate. People don’t admire weakness. Offstage, however, I always question and compare myself, unfortunately. There’s so much work that I haven’t released. I have a music video that never saw the light of day because it wasn’t up to par. I envy some performers who are able to release work with full confidence.” Talking to him, it’s hard to discern whether the constant discontent comes as a result of the craft itself, or from the constant rejection he endured throughout his life. “I suffered a lot from seeking validation, from wanting people to accept me and see me for who I am. Now I’m in a place where I regret exposing myself so much. I question things ten times before posting anything on social media. It’s a struggle, which is why lately I’ve been focusing more on being behind the scenes, and collaborating with other artists.”

![]()

Khansa is hard to pigeonhole. He is both masculine and feminine, Oriental and Western, classical and modern. “It’s balance. Even Mohammad Abdel Wahab used Western influences in his songs. Every single piece comes from somewhere else, and this is the beauty of the art form. With globalisation, everything is becoming multicultural. It wouldn’t make sense not to be influenced by other cultures.” Khansa is an avid gleaner of culture, and an insatiable student of the Arts, constantly on the lookout for inspiration, and frenziedly searching for answers about his self in the realm of the imaginary. “The West constantly gaslights us into thinking they are the main exporters of culture. Their culture is almost entirely borrowed from our region, Africa, India and Asia, so why would being inspired by other cultures take away from my own sense of identity? In the end, what you do is who you are, and nothing can take that away from me.” When asked whether he considers his life well-adjusted, he instantly chuckles. “I’m more committed to my work than my personal life. I prioritise working sessions over coffee with a friend or a birthday party. When I go out at night, I can’t wait to run back home to continue creating, and for now, that’s not something I feel sorry about.”

Although Khansa has been reprieving himself from the limelight lately, the artist is more determined than ever to resume his artistic output. Equipped with a team of people attentively cradling his career, and having recently signed a record deal in London, the performer is challenging himself yet again to reach new heights. “I’m currently working on an Arab dance pop album inspired by my experience as a belly dancer. It fuses the Arabic language with pop sounds from across the genre, and is an exploration of nightlife, and all the experiences that come with it.” In what seems to be his most mainstream project yet, it can also be perceived as a natural progression of his body of work. Do not expect him to label himself a popstar, though: “I will never say I’m an Arab pop artist. With the American marketing model, pop artists are encouraged to claim that they are completely self-made. There’s no such thing. Art is collaborative, and a culmination of people’s proficiencies. I’m not just a pop singer on this project. I’ve studied music production, sound-creation and songwriting so that I can actively participate in the making of this album from all ends, and so that the process can be entirely collaborative.”

Khansa’s most universally acclaimed collaboration to date is his guttural performance in director Dania Bdeir’s short film Warsha. The film garnered unanimous praise in the festival circuits, including Sundance, and was shortlisted for the Oscars. Khansa himself won a myriad of international acting awards, a rare feat considering it was his first-ever professional screen-acting performance, devoid of any dialogue.

Notably, he is completely unaware of said awards. “Honestly, I know I won a lot of acting awards, but I have no idea which ones they are. You should ask Dania and let me know.” Turns out, he’s won seven Best Actor awards from film festivals in Italy, France, Greece, Turkey and the United States. His delivery as a marginalised Syrian construction worker in Lebanon is uncharacteristically understated. Khansa spent days overexerting himself in preparation for the role, working on construction sites and meticulously crafting the choreography for the film’s stunning finale. “The film reflected my life, and Dania saw that. She’s the one who kept me going. We all need a person like her in our lives.” What should have been a meteoric launch for a promising acting career was treated with surprising ephemerality by the artist. “I put everything I’ve done in my life into that film, but I don’t want to be an actor. There are other actors who can do so much better. I did enjoy challenging myself though.”

As the conversation comes to an end, it becomes incrementally clear that what drives Khansa forward is neither fame nor acclaim, but rather the unquenching thirst for a challenge. His arduous creative process has proven to be rewarding, albeit all-consuming. “My biggest challenge today is to be able to do work while preserving my health and my life as a person. I need to find balance.” Until then, it is worth noting that when stars self-implode, they herald supernovas.