News

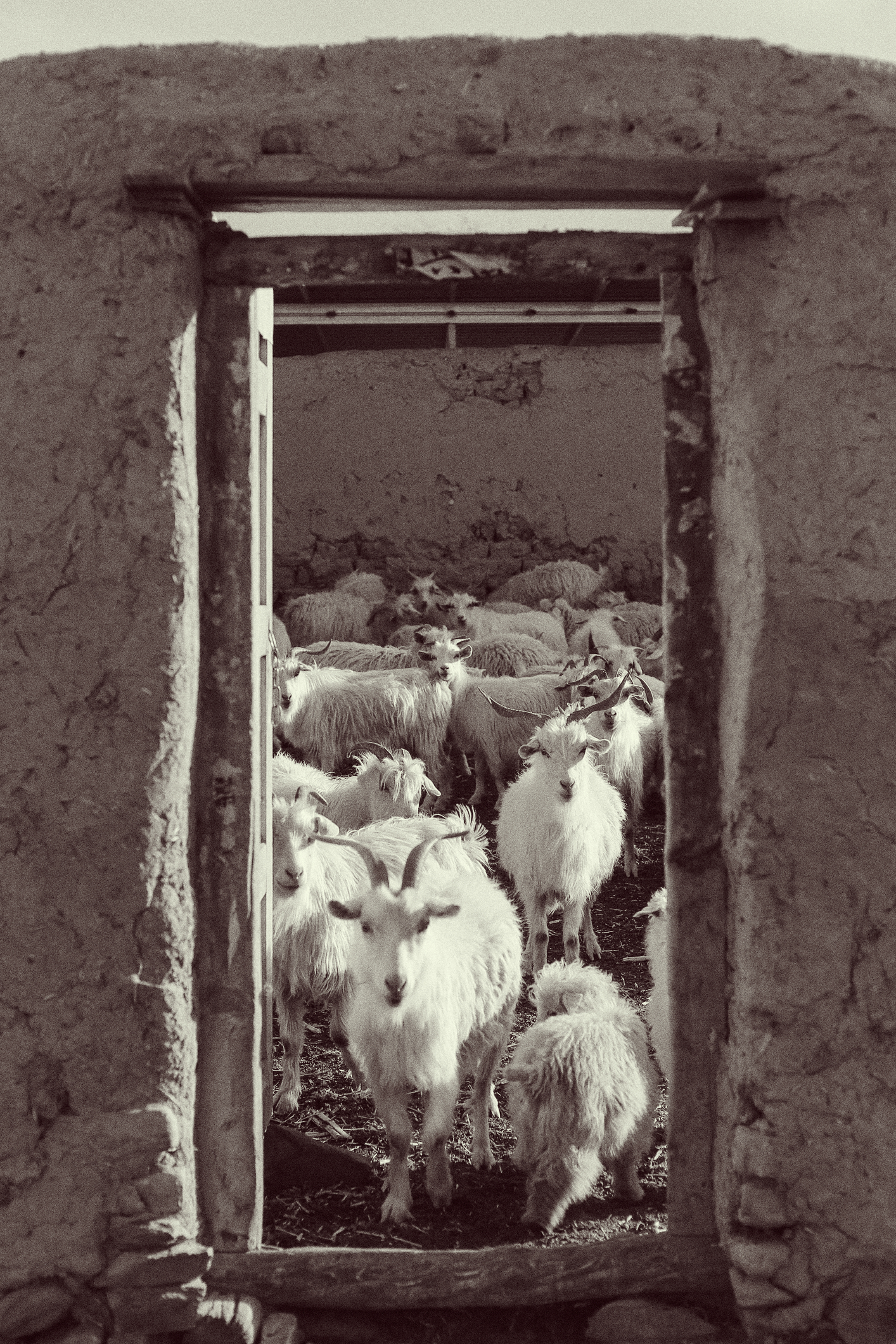

Travellers in rural Hadramaut will undoubtedly have seen women dressed in black, their heads adorned with long, pointed, woven straw hats, tending to their flocks of sheep. Herding remains vital to Hadrami life, especially for nomadic and rural communities. In Hadramaut, gender roles are distinctly defined; the task of raising, caring for, and herding goats is exclusively assigned to women – a responsibility that demands arduous daily labour.

Rarely does one find a shepherdess alone with her flock as herding is a communal endeavour. Neighbours often band together, each tending her own herd. Typically, at least two women embark on this task together. They depart their homes before sunrise, supplied with food and water for the journey ahead.

As a young girl from the Hadramaut coast, I was always captivated by the sight of these female goat herders during our family trips to the Valley. To tend to flocks in the scorching summer heat, often reaching 50 degrees, was a feat beyond my imagination. Yet, they moved with an effortless grace, their bodies in perfect harmony with the land. Their gentle yet firm command over herds of sometimes dozens of goats was truly mesmerising.

I travelled to the Hadramaut Valley to write this article, fascinated by the landscape of mud-brick houses and verdant farms along the way. One can instantly notice how Hadramaut’s unique architectural identity reflects the Hadramis’ deep-rooted connection to the land. With preconceived notions about these women, I set off, only to have my assumptions swiftly challenged.

My journey began in Al Ghurfah, a town nestled in the Hadhramaut Valley, about nine kilometres from the capital, Seiyun. There, I encountered a 31-year-old woman who preferred to be referred to as Umm Saleh. As she tended her flock in the valley, she was dressed entirely in black from head to toe; she wore a heavy black velvet abaya, black gloves, and a black face veil, along with sunglasses, and carried a smartphone. It seemed that the goats knew her instinctively, their behaviour mirroring that of a child recognising the mother by her voice and scent. She happily agreed to talk to us, suggesting we have our conversation at her home rather than in the valley, so as not to distract her from her flock. And so, we went to her home in the afternoon.

I anticipated a simple mud-brick home and a shy woman, her identity concealed by the black attire we had seen in the fields. Umm Salem, her mother, a beautiful woman in her fifties framed by a colourful headscarf, greeted us at the door. She welcomed us into the guest room which was unexpectedly modern with curtains and a majlis that held a tray of milk tea, coffee, dates, and biscuits. As I adjusted to this surprise, a stunningly beautiful woman entered, dressed in a vibrant mukhor. Her long black hair cascaded over her shoulders, and her face was adorned with makeup. “Did you recognise me?” she asked with a smile. “I’m Umm Saleh!” The stark contrast between the demanding physical labour of herding and her evident dedication to self-care and beauty was wholesome.

During my journey, I managed to meet five shepherdesses from different generations and speak with four of them. The husband of the fifth, despite her willingness to share her experiences, refused to let us meet with her. Each home I visited offered a unique perspective. For instance, in Umm Saleh’s home, I encountered two generations of shepherdesses: her mother, her fifties, and her daughters. In Fatima’s home, a sixty-year-old shepherdess, I found four generations living under one roof: herself, her daughters, daughters-in-law, and granddaughters. They reside in the Shuhuh region, one of the most famous valleys in the Seiyun Directorate and the closest to Seiyun.

Through my conversations with these women, it became clear how societal mindsets, norms, and traditions changed over time. However, across generations, the responsibility of herding and caring for both families and livestock has primarily fallen on women. As Fatima aptly stated, “Caring for the sheep is like caring for one’s own children.” From the shepherdesses’ perspective, women are better suited to the demanding tasks of herding due to their inherent compassion and patience, qualities essential for working with animals.

As Umm Saleh put it, “In Bedouin society, women are expected to work hard.” This means that women are constantly on the move and engaged in labour. When I asked why men didn’t tend to the flocks, the response was unanimous: “Herding is women’s work here.” Bedouin men are often found working in Gulf countries or serving in the military or tending to their farms. The responsibility of selling the livestock, however, typically falls upon men.

A shepherdess starts herding by tending to her family’s livestock. After marriage, she may bring her own sheep to her husband’s home or help tend to his family’s flock. A woman also has the freedom to choose whether or not to continue herding after marriage, depending on her circumstances. In Fatima’s home, I met her daughter-in-law, a woman in her twenties. She told me that she used to herd sheep at her parents’ home but preferred to rest after marriage.

Umm Salem, however, didn’t favour rest, as she told me, “Herding is my thing and I love it.” She married at the age of thirteen and was already herding with her mother. After marriage, she continued to herd, while her husband was working abroad and was responsible for sending money to the family. But after he left for good, herding became the family’s sole source of income, making it a necessity for her. Umm Salem doesn’t rest, even when she’s pregnant. Once, she went into labour while out herding.

Umm Salem has given birth to eight children – four girls and four boys – all through natural childbirth, and she breastfed each of them for two full years. After giving birth, she would rest for only twenty days before returning to her herding duties. She says, “My husband has no mercy on me,” as he expects her to work tirelessly. Despite all of this, she doesn’t receive any of the profits. Her husband sells the goats and keeps the money for himself. Umm Salem doesn’t dare ask her husband for her share, even though she accompanies him to sell the goats, as she describes him as “short-tempered.” Even when her daughters get married, their husbands take their dowries and only give them a small amount. When I asked if her sons work, she replied that they don’t and that their allowance is from the sale of the livestock. Although Bedouin society values livestock, the men, according to her, are too embarrassed to herd sheep due to teasing from their peers in non-Bedouin communities. Therefore, they prefer to remain unemployed rather than herd sheep.

Umm Salem’s experience reflects the significant challenges faced by Bedouin women, where their traditional maternal roles intersect with economic and social pressures. Despite the harsh conditions, Umm Salem perseveres in fulfilling her role as the family’s provider, even at the expense of her personal comfort and material rights. I was amazed by their ability to endure such hardship while balancing it with society’s expectations of a woman’s role at home: caring for children, cleaning, cooking, and attending to their husbands’ needs. The more I heard their stories, the more I was impressed by their strength and resilience as they recounted their struggles with a bright smile. They appreciated that someone was listening to them with full attention and care in a society where women’s herding duties are taken for granted.

A shepherdess’s day begins at dawn. She tends to her household chores and prepares breakfast, often bread baked in a tannour. Afterwards, she readies herself to “herd” her livestock. First, she inspects the flock, separating any sick or pregnant sheep to be left at home. Then, the shepherdesses set off towards the “masial,” a grazing land with bodies of water. One woman takes the lead, guiding the flock along the path, while another follows behind to ensure that the sheep stay together. Once they find a suitable spot, they stop and direct the sheep to do the same.

These days, herding typically concludes before midday to avoid the scorching heat, protecting both the shepherdesses and their flocks. According to the women, goats and sheep have been sensing the rising temperatures compared to previous years, tiring easily when exposed to prolonged periods of sunlight. The shepherdesses take a break during the afternoon, seeking out a shady spot to shelter themselves and their flock from the sun’s rays. They rest until sunset, then return home in the late afternoon.

Each shepherdess knows her flock by heart, even when it numbers in the hundreds. She instinctively recognises them as she knows her own children. Using a variety of vocal tones, each carrying a different meaning, she communicates with her flock. For instance, a low, rolling ‘R’ sound is to call the animals to water.

According to the older shepherdesses, herding was more arduous back in the day. They spent longer hours herding, and sometimes even stayed outside overnight without means of communication like the smartphones available now. They would also take cooking equipment and ingredients with them to make food. Umm Salem says, “On herding days, I used to cook rice with goat’s milk,” which, as she describes it, was delicious, nutritious, and better than today’s nutritionally void food.

The older shepherdesses believe that young shepherdesses today are physically weaker due to differences in their diet and modern lifestyle. Fatima mentioned that her daughters are more preoccupied with their phones than herding and that their focus and connection with the goats have weakened.

Umm Saleh also believes that the profession of herding is on the verge of extinction as the number of shepherdesses has decreased significantly in her area. She even doesn’t want her twelve-year-old daughter to herd and encourages her to focus on her studies and complete her education instead. Umm Saleh herself would like to quit herding, she says, but her mother’s old age and inability to work have forced her to continue working to support her family.

Umm Mohammed, Fatima’s daughter-in-law, tells me that many families now hire a shepherd from outside the family to herd the livestock instead of the women, or in some cases, they bring in Ethiopian shepherdesses. However, Fatima believes that a shepherd who’s “hired” does not treat the livestock properly and cannot build the same strong bond that exists between Bedouin shepherdesses and their herds.

Young shepherdesses are embracing modern technology. They own smartphones and are active on social media. Umm Salehm, for one, is a Snapchat enthusiast who enjoys keeping up with the latest celebrity news. Even while herding, they often use their phones to connect to the internet.

When I asked the shepherdesses about the challenges they face, I anticipated hearing about the physical hardships of working under the sun. Instead, they unanimously pointed to a far more profound challenge: the scarcity of food for their goats and the absence of rahma, which means “mercy” in Modern Standard Arabic. In Bedouin culture, however, rahma means rain. I found this word to be a beautifully evocative term for rainfall.

A primary reason for the dwindling grazing lands is the prolonged drought and the encroaching urbanisation of the Valley. Once a fertile agricultural valley, the proximity to the city of Seiyun has seen a rapid increase in residential development, transforming the landscape and depleting vital resources.

Fatima, the eldest among them, views herding as a way of life. Despite being well over sixty, she still tends to her flock, with the signs of fatigue and exhaustion evident on her face. For her, herding is part of her identity. Being a shepherdess is a source of pride and self-worth. In her family, sheep are considered the exclusive property of women, and no woman is forced to herd. She chooses to do it voluntarily. However, the men in Fatima’s family, as those in Umm Salem’s, show no interest in herding. They do not see it as a suitable profession for themselves. If she asks one of her sons to herd, he would refuse and say, ‘If you don’t want them, sell them.’

Traditionally, in our Arab world, demanding work is seen as a man’s domain. However, talking to these shepherdesses, I’ve realised that Bedouin men equate herding with childcare—a role typically associated with women. They believe men lack the patience and nurturing nature required for caring for young ones, whether human or animal. In contrast, the shepherdesses view their goats as their children. Fatima shared how attentive she is to newborn kids. If one struggles to feed, she’ll cradle it and patiently encourage it until it can nurse. If that doesn’t work, she’ll bottle-feed it like a baby. The women I spoke with believe that the personality of a shepherdess is stronger than that of a housewife, as it involves dealing with external challenges and interacting with different people. They also told me that they don’t feel fear or anxiety when they go out herding, and none of them have reported any form of harassment or abuse. The community respects the shepherdesses and their work.

The experience of shepherdesses in Hadhramaut is a living testament to women’s ability to shoulder responsibilities and adapt to challenging circumstances. Through dedication and hard work, they overcome obstacles and prove that women are capable of taking on challenges and making significant contributions to society, even in roles traditionally considered masculine.

Herding in Hadhramaut is not merely an occupation; it is a part of a woman’s identity and a means of expressing her strength and independence. The stories of these shepherdesses are lessons in courage and dedication, reminding us of the importance of recognising and supporting women’s efforts in all fields.

Words: Shaima Bin Othman