Everything

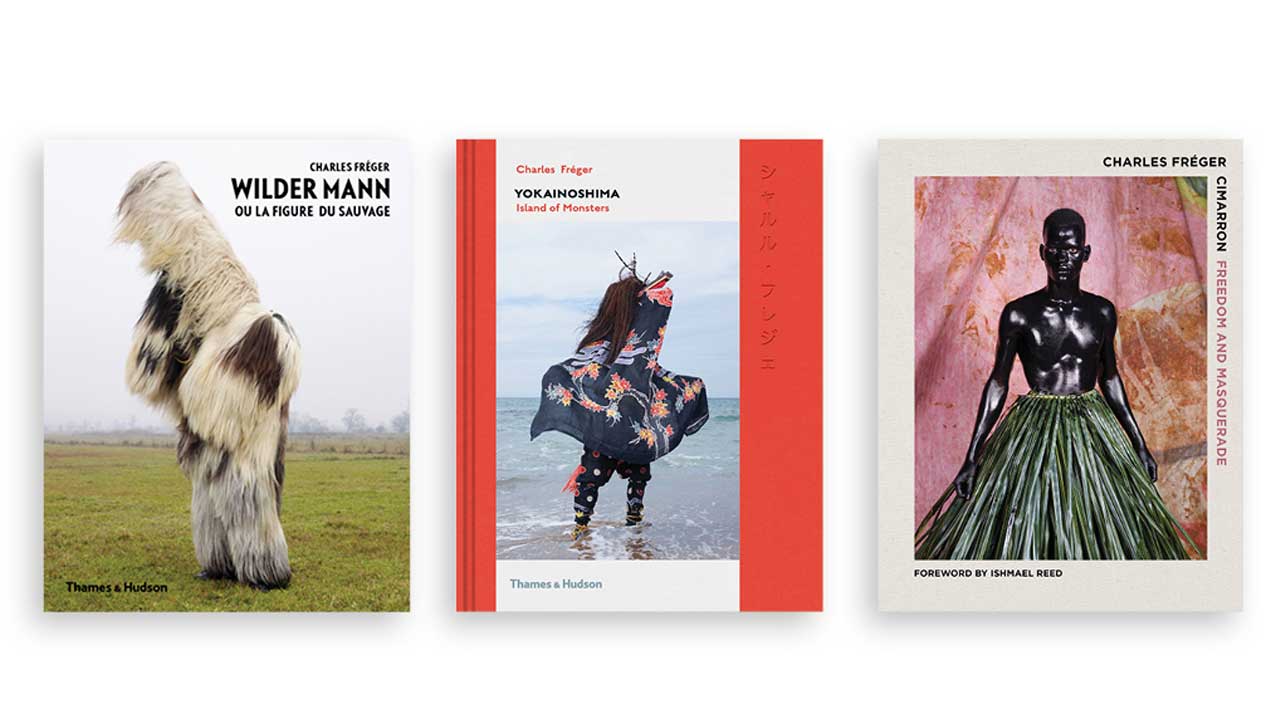

Since 2010, French-born photographer Charles Fréger has been exploring folk rituals and traditions across various cultures. His long-term photographic research project has seen him document masked winter rituals on the European continent in “Wilder Mann” (2010-2011) and masked rites in Japan with “Yokaînoshima” (2013-2015). In 2019, a solo exhibition at the Château des ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, France, unveils the third chapter of this ambitious series of portraits, which saw Fréger, 44, focus on Afro-Carribean and African- American cultures between 2013 and 2018. Travelling across a geographic space stretching from the southern United States to Brazil, Fréger drew up a non-exhaustive inventory of masked rituals performed by the descendants of African slaves.

Cimarron is a term borrowed from Spanish-American culture that refers to the name given to enslaved Africans who have escaped their captors and struck out on their own. These runaways, having found their freedom, went on to establish their own communities or join up with indigenous peoples to forge new identities. Also the name of Charles Fréger’s latest corpus, Cimarron explores the composite and diverse nature of Afro-Caribbean and African-American cultures from Brazil, Colombia, the Caribbean islands and Central America, and as far north as the southern United States as many seek, through the laws of masquerade and entertainment, a way to avenge the past and reinvent it.

In his work, elaborate masquerades unfold in which, between masks, makeup, costumes, adornments and accessories, intermingle African cultures, indigenous and colonial, caught in the vertigo of a multi-secular syncretic movement. Vividly coloured silks and cottons combine with woven fibres, leaves, feathers and body paint in spectacular shapes made from all kinds of materials, from bull’s horns to crocodile skin. The viewer is immediately thrown into a colour- blast carnival in which props are front and centre and include emblems of slavery and slave masters – ropes, sticks, guns and machetes. These tools become an emancipatory restaging of the relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor, and the mask embodies a gaze turned on one community by another.

Cimarron defines a new genre of documentary portraiture that extends and deepens our sense of the human past and the present. ICON sits down with Fréger to ask a few questions and discuss his exploration of the invisible cultural traces found among people of the world.

ICON: What does it mean to create a portrait?

CHARLES FRÉGER (CF): “I like the way people represent themselves in the community and the aesthetics of groups in which traditions are alive.”

ICON: When you were among the Himba people in Africa, you wanted to have your body painted like them. Why?

CF: “It was 2007, it was a special moment … I was trying to be physically and humanly connected to [the Himba people] in an attempt to understand them. But it has to do with exoticism, that is, with what it means to be a European before an African tradition. I soon realised that being like them didn’t make any sense. Indeed, I needed a certain distance from the subject.”

ICON: So distance is needed to be a photographer?

CF: “I think so. What do you think?”

ICON: I agree. I think we can look for empathy, but to an extent. And one of the interesting traits of your work, in my opinion, is being the narrator of intimate and fabulous encounters.

CF: “Feeling foreign is a way to respect others. Which is contrary to globalisation and makes people believe they can understand the world by simplifying it. Instead it’s getting more and more complicated and I respect keeping my distance.”

ICON: Your goal, in fact, is to tell how the human being expresses them self, at any length.

CF: “Exactly. And this too is antithetical to social media, which offers a prefabricated language. I often read comments on my photos on Instagram as portraits of companies in danger of extinction. False. And stupid. It’s like saying that those who are not on social media do not exist.”

ICON: How is your work put together?

CF: “I often follow suggestions that come to me from old books, but also current stories. Then I’m looking for someone to work with me in the country where I want to go. They usually work in the cinema between legal offices and production secretaries… and they must have the energy to contact the groups to photograph and make an agreement.”

Charles Fréger’s “Cimarron” runs until April 14, 2019, at the Château des ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, France, and is supported by the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès.

THIS ARTICLE APPEARED ORIGINALLY IN THE APRIL 2019 EDITION OF ICON MAGAZINE.

SUBSCRIBE HERE TO RECEIVE TWO PRINT EDITIONS PER YEAR FOR $30AUD