News

ATMs. Solar panels. Power adapters. Ordinary objects in most cities, but in Beirut, they reveal something deeper about the city’s fragile infrastructure. The crises Lebanon endures can almost be traced through them—dissected and deciphered in plain sight.

Dia Mrad’s work fixates on precisely that. A Lebanese architect turned photographer turned artist, his evolving practice revolves around the city’s buildings and infrastructure, highlighting what is lost or forgotten over time. He surfaces the objects and invisible systems we pass by every day, turning the bones of the city inside out. His work gained prominence after the Beirut Port explosion on August 4, 2020, documented in his first solo exhibition, The Road to Reframe, which he describes as having “rushed” him into the art world. Since then, he has participated in the Sharjah Architecture Triennale 2023, exhibited in Dubai, and joined the Misk Art Institute’s Masaha Residency in Saudi Arabia, as well as a residency at Cité des Arts in Paris.

After years of continuous creation, Mrad took a pause to reflect, and now he presents Shift, his first large-scale installation at WeDesignBeirut, the city’s annual immersive design event. The festival celebrates Lebanese creativity across exhibitions, installations, talks, and workshops spanning product design, architecture, interior design, and functional art. By activating historic and architecturally significant sites, WeDesignBeirut highlights Beirut’s cultural heritage, honours tradition, and fosters a sustainable creative ecosystem that connects local design to a global audience. The event was founded by Mariana Wehbe, Mrad’s neighbour and a longtime friend of over ten years.

Sitting together on a grey couch at Wehbe’s home, the two discussed the art of pivoting, the ‘unintentional’ resilience of the Lebanese, and the experience of collaborating for this year’s edition of WeDesignBeirut.

Mariana: So, Dia. How old are you?

Dia: I’m 34. As I’ve mentioned, it feels like I’ve lived through crisis after crisis in Lebanon, one after the other, since I opened my eyes.

Mariana: I think it’s been generations of that, unfortunately, for us.

Dia: But I also see it as a field to work with. Beirut gives us this condition where the whole city becomes a studio, because we’re constantly negotiating collapse. It’s a kind of lifelong education, you’re always learning.

Mariana: They say in big tech businesses that the ones who make it to the millions and billions, there’s something that they do, which is pivoting. They have their business plan, they launch it, then they realise that there’s a big gap and they have to change it completely. When they pivot, they become successful. We’re constantly pivoting in Lebanon.

Dia: For me, I didn’t think that being in my mid-30s, I would be doing what I’m doing now. I mean, I did study architecture…

Mariana: But what do people define you as?

Dia: I don’t think people know exactly how to define me, and maybe that’s natural. The practice is still unfolding, and I’m still learning what shape it wants to take.

Mariana: When you first began, you were a photographer. You were shooting the architecture of our city, and then from that, the Beirut explosion…

Dia: Even before that, I had a master’s in architecture. That was the path I chose. My first pivot came with Lebanon’s 2017–2019 housing crisis. When loans stopped, architecture froze. By the time I graduated, there was no work, and leaving the country felt like the only option. Photography, which had been a passion, became a way to stay. At first, it was just posting on Instagram, but people responded, and that became my first real pivot. From there, I moved into real estate photography until the explosion pushed me again—this time toward documenting the present more directly.

Mariana: From there, did you always feel there was something triggering you to not just do photography or something itching at you? Because you were doing photography as an architect.

Dia: Even as an architecture student, I worked with concepts, volumes, materials, and objects. Photography was a tool I used to observe sites, then design based on those observations. It was always a way to reach an end result, not the end result itself. That’s why I never present myself as a photographer. I describe myself as an artist working primarily with photography, because it’s just one tool within a wider practice. And that’s why this moment, presenting my first sculptural work at WeDesignBeirut, feels like a continuation rather than a rupture.

Mariana: You also pulled back for a while. You were doing all these shows, and you just pulled back from everything. As an artist or as a creative, you need to pull back sometimes. You didn’t know where this was going to take you. I remember you were experimenting in the house.

Dia: I was rushed into the art world when the explosion happened. We were in survival mode, and everything moved too fast. Three years in, I was moving from one job to the next, one exhibition to another. I was doing well, but it left me no time to think. I was executing constantly, and at some point, I felt I needed to step back and understand what I was actually doing.

I never planned to be a full-time artist, but here I was. So I asked myself: what do I do with this platform I’ve developed? Where do I take it? I let go of commitments, pulled back, and rethought my priorities. Photography had always been a tool, evidence to make a point, but it started to become the end result. That’s when I began asking: am I a photographer, or am I an artist?

Mariana: Do you think that society has taught us that we need to put everything in a box because it makes everybody feel comfortable? Do you think that boxing made you rethink, I need to be this or that?

Dia: At some point, photography alone wasn’t enough to express what I had in mind. I had to accept it’s okay not to fit into one category, and to challenge myself. Many people are happy staying within one medium, but I felt my work needed to expand and evolve.

Now the work has expanded into installations, while still including photography. For me, this isn’t a rupture but a continuation. I’m asking the same questions, but instead of presenting them through images, I’m embodying them in objects. The transformation is in the medium, but the subjects remain: infrastructures, debris, fragments that usually escape notice. My role is to bring those elements forward and let them tell their story.

Mariana: What could you tell us about your installation for WeDesignBeirut?

Dia: It’s a tall two-meter stainless steel object, sculptural, but also functional. It’s a power supply indicator—a system that tells you which source your home is running on, whether solar, generator, or government electricity. I took this everyday function, which embodies the Lebanese condition, and transformed it into a kind of negotiation with infrastructure itself.

Mariana: You’ve done an exhibition about this.

Dia: I’ve done a photographic installation titled Power Shifts for the 2023 Sharjah Architecture Triennial, where I used the solar panels on the rooftops in Lebanon to talk about the economic crisis, which resulted in a power crisis, which resulted in us developing these individual solutions. Every household was responsible for supplying its home with electricity. For me, that was an observation that the proliferation of solar panels on the rooftops really tells us that something is…

Mariana: Wrong?

Dia: Not wrong, but something is happening…

Mariana: There’s clearly a need for it, but where does that need actually come from? It’s not because the country itself is built on sustainability, since solar panels are usually associated with places like Norway or Switzerland. Instead, you have this lawless, chaotic, broken state, and yet suddenly everyone has solar panels. Do you think this urgent need has also revealed the possibility of a positive outcome?

Dia: For sure. We may dislike the word ‘resilience,’ but it shows how much people here adapt to sustain a life they want to hold onto. Everyone in Lebanon pivots—you throw a challenge at us and we adjust. We even say we make lemonade out of lemons. But the danger is that this constant adaptation stops us from questioning why collapse keeps repeating.

Mariana: We’re experts at making lemonade out of lemons.

Dia: It does show a spirit of tenacity, the will to survive and keep going. But it’s also not entirely positive, because it stops us from looking at why this survival instinct is needed in the first place. That’s where my work comes in, taking these invisible systems we’ve grown used to and forcing them back into view. The object at WeDesignBeirut is a two-meter relic from the future, telling you which power source your house is running on. Something so ordinary, yet here we depend on four different sources. It’s become normalised, almost invisible. My role is to make people see it again.

Mariana: I think you’ve brought it all together. This year’s edition of WeDesignBeirut centres around forgotten places and spaces, and these fifty years of war. As you said, we pass by buildings and forget their history, their stories. They fade into the background and become unconsciously invisible.

Dia: We have these landmarks in the city that just sit there. We pass by them every day without really seeing them. What I value about WeDesignBeirut is that it reopens these sites, brings them back to the forefront, and insists on their stories. Entering Burj El Murr is a big deal for all Lebanese people, not just me.

Mariana: I was so close to going to jail for it.

Dia: We’re resurfacing things that have become invisible, though they should never have been. Burj El Murr is as central to our collective memory as the silos..

Mariana: As the Holiday Inn.

Dia: So all of these objects, including the power supply indicator I’m making, are to remind you that there’s something completely wrong with this place, and the more we ignore it, the more it festers and develops and becomes a bigger problem, and then you can’t fix it.

Mariana: Gregory Gatserelia, the curator of Totems of the Present & the Absent at Villa Audi, is, in my opinion, a master. He launched talents like Najla El Zein and Ranya Sarakbi, among others. When he saw your piece, he actually called me and said, ‘This guy has so much potential.’ I knew at the time you were in a place of uncertainty, like a caterpillar breaking out of its cocoon—painful, but inevitable. There was nothing to do but wait for that transformation. And then Gregory calls me and says, ‘This Dia is really talented.’ And I thought, yes, he’s on the right track.

Dia: What did you think when you saw the installation?

Mariana: It was a complete continuation of who you are because I remember seeing the exhibition that you did in Dubai of all the ATMs in Lebanon. What you’ve been able to see through your lens and create now through your art are things that we don’t see. When I saw what you were doing, it was phase two of this movement for you. I wasn’t surprised. This is your DNA, this is who you are.

Dia: From my side, I was also a little worried. I needed to show up and represent.. I’m still in an experimental phase, branching into forms I hadn’t worked with before. Presenting something at this scale, in this medium, and on a public platform like WeDesignBeirut is a big step for me.

During the time I spent researching, I treated it almost like a residency. I developed a framework to guide my practice, connecting earlier works while informing the new works to come. These new works were all planned sculptures, five or six projects, all installations. I was a bit surprised when this framework evolved into what I now call architectural installations, a nod back to my training. But I told Mariana, I felt a continuity in my practice rather than a disruption or a break. WeDesignBeirut arrived at the perfect time, giving me the chance to place my first sculptural work in a context that truly hits home. I had always seen WDB as a design platform, but what struck me was how open it is, bringing together art, design, students, and practitioners. It turned out to be exactly the right place for this work to begin.

Mariana: It’s designing our city. We have everyone involved this year: jewellers, product designers, and even two chefs. It breaks all the traditional barriers, because we approach it so intuitively. We even gave Khaled Muzannar, a composer, the space to create a huge installation for us. For him to say, ‘We have an opinion in this situation, and we can still create something that has dialogue, reasoning, and beauty, something that could even be placed in your home.’ That’s the reminder this exhibition offers. It’s meaningful, it’s rooted in the Lebanese context. It’s not just a $100,000 table.

Dia: Yes, it has meaning, and it comes purely from Beirut. When you say WeDesignBeirut and then look at this object, you see how it couldn’t exist anywhere else. Outside Lebanon, it would be obsolete. Here it resonates because it grows directly out of our daily reality. That’s also where the brief for Totems of the Present & the Absent at Villa Audi really pushed me to develop the work. I had already explored electricity in my 2023 series, Utilities, observing and presenting it to the public. Then came the brief: ‘create a totem for the present and the absent.’ And in Lebanon, nothing is more present and absent than electricity—it’s there, but it’s not. You can put up solar panels, generate it, and bring it in. The totem I designed emerged from all those conditions, and somehow it all came together.

Mariana: I think you are brilliant and creative, and, if I may say so, everyone should keep their eyes on you. I have seen your journey, and this is only the beginning. You also brought us a co-sponsor, which is very rare. That generosity stood out because usually there can be tension—I can have tension easily with people because of my character, and also because people don’t always understand how extremely busy I am and how fast things need to move. What happened with you was different: you came in and actually called someone we wouldn’t have had access to. Not many people do that, and I was grateful. There’s a lot of generosity in our friendships.

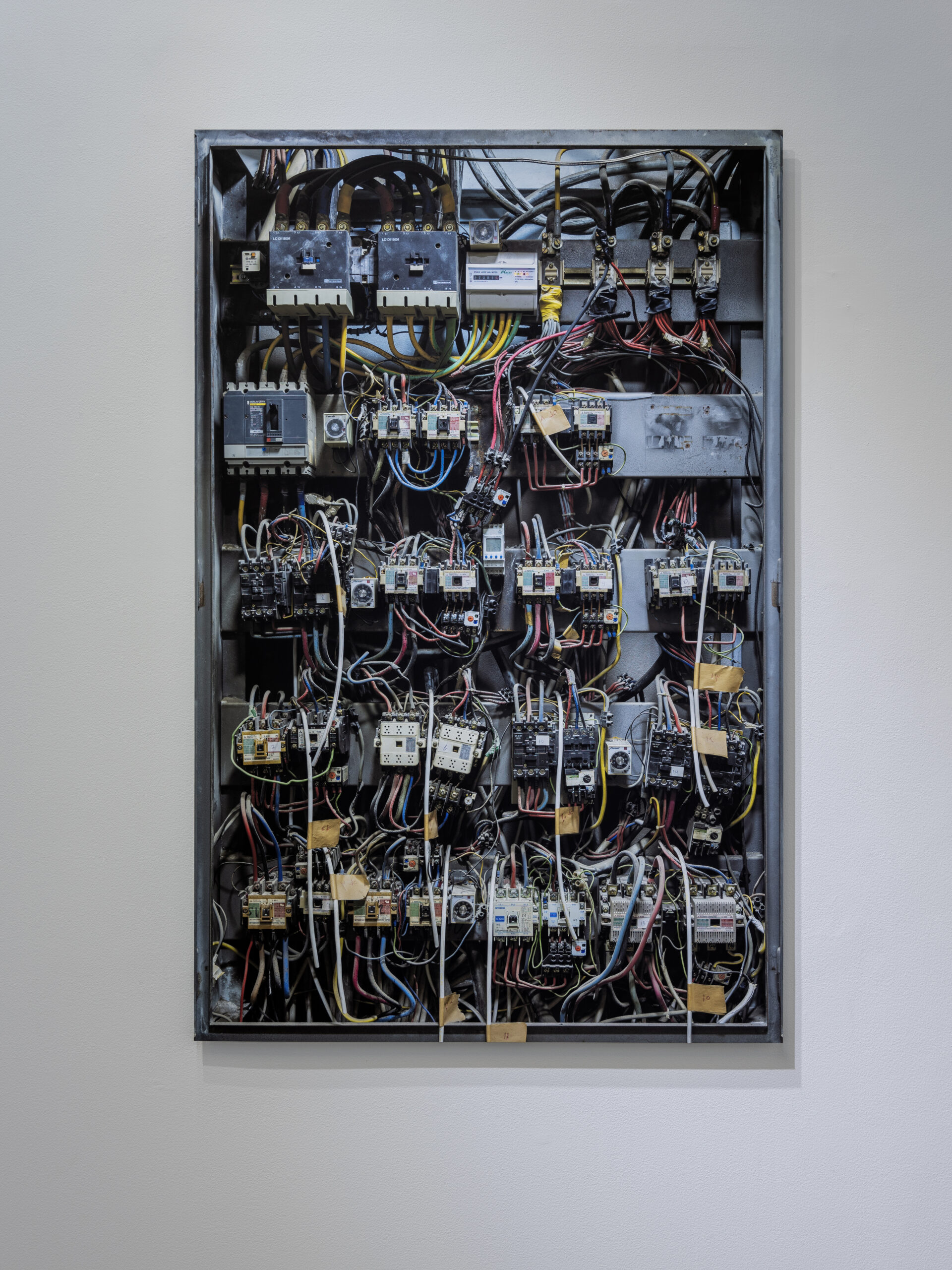

Exhibition view, Utilities, Dubai, 2023

An electricity box layered with wires and switches, exposing the informal infrastructures sustaining daily life.

Dia: Honestly, I was a little worried about working together because I’ve known you for years. We’ve been close friends, and I’ve always been supportive. Even during the last edition of WeDesignBeirut, people assumed I was involved simply because I was so present. I’ve seen how you work, and I really appreciate what you’ve built; it’s a very special role you’ve created for yourself. Still, I had some concerns, because working with friends isn’t always easy, and many friendships don’t survive it.

Mariana: I always say it’s all about the intention. If your intention is in the right place, you will never see a 60-page contract ever.

Dia: But we haven’t had any trouble working together. And yes, I answered all my emails on time!

Mariana: Remember, we were sitting right here on this sofa on the last day of the Israeli war on Lebanon. We had a phone set up and filmed ourselves talking for 30 minutes while planes flew overhead, bombs fell, the Quran playing, tequila drinking, jazz playing. We kept having this conversation: ‘What’s going to happen? Could we die tonight? Could this be it?’ And we actually decided to film it.

Dia: It’s strange, when you think everything could end, what do you really hold on to in that moment? What are your thoughts? At that point, I was in a very delusional place, thinking everything was going to be okay. But it affected me profoundly, giving me more time to reflect and also to question what really matters. How much can my practice as an artist help when people are dying all around, and you could be one of them at any moment? I came out of it with a stronger motivation to create work that truly engages with our state and condition, with daily life itself. My work comes from those encounters, whether it’s electricity, water, ATMs, or architecture, the things we live with every day and what they reveal about our present condition.

We’ve definitely been unearthed. We’ve been earthed and unearthed many times. What drives me is unearthing the systems of daily life and giving them form as contemporary objects. Electricity, rubble, facades, and circuits are the materials through which the present is already being inscribed into history. My practice works with these fragments to hold the reality we live in today while opening space to imagine what futures might emerge..

Sami: So, is everything going to be okay?

Mariana: Yes

Dia: No…

Mariana: That’s Lebanon for you.