News

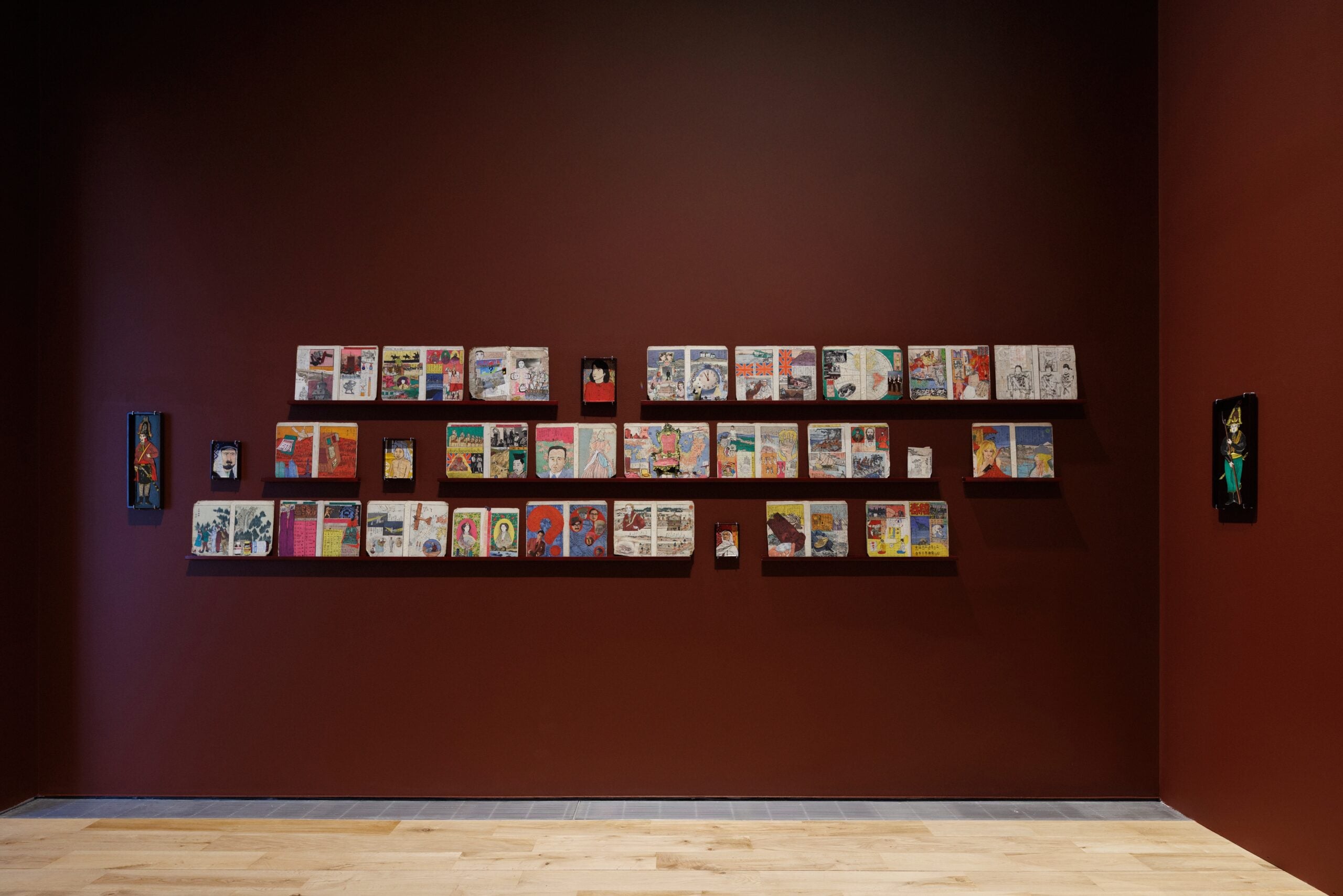

The French-Syrian artist Bady Dalloul has always possessed an imaginative mind that dreamt of worlds transcending our own. As I enter his latest exhibition, Self-portrait with a cat I don’t have, at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, the soft-spoken artist brings to my attention a pair of displayed notebooks, a telling opener of the show, that he and his younger brother, Jade, filled with drawings and writings as teenage boys. The story goes that when the Paris-born artist was younger, he and his brother conjured up a childhood game while visiting their grandparents in Damascus between the late 1990s and early 2000s.

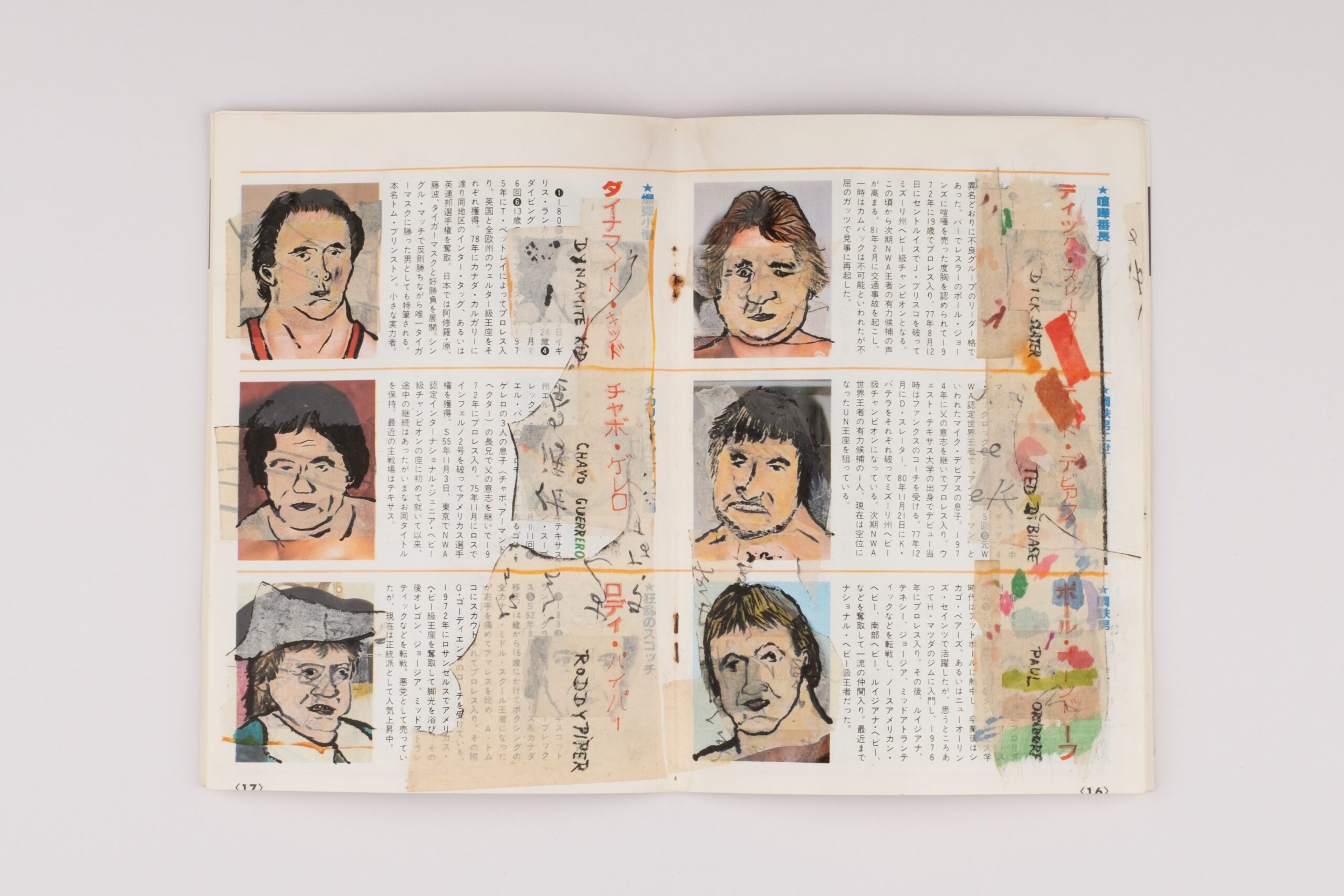

They scribbled the pages of their grandfather’s diaries with written and pictorial details – made-up maps and magazine cut-outs – of their own imaginative lands, named after themselves, ‘Jadland’ and ‘Badland’. “As you can imagine, some of the summers were very long and we were bored a lot. We started imagining that we were kings of fictitious countries,” the Dubai-based artist tells ICON MENA. “It was more of an obsession in childhood, not knowing really what to do with it. It would take hours of my day. I don’t consider them works per se, but they are somehow my genesis.”

![]()

Born in 1986, Dalloul was indeed immersed in an artistic environment right from the beginning. He happens to be the son of two of Syria’s reputable, multidisciplinary artists, Ziad Dalloul and Laila Muraywid, who encouraged him to use his creative streak, perhaps even unknowingly setting him on his artistic path through their continued guidance. “They surely impacted me,” he says. “Most children run around and make noise, but instead, they gave me a pen. I remember my parents teaching me how to draw and my father showing me how to hold a pen. I think they were great parents in giving me the confidence to believe that I could do everything.”

“But I also grew up seeing firsthand what it meant to be an artist in Paris in the ’80s and ’90s, which was very different from now,” he continues. “Today, diversity is celebrated. In Paris, at the time, it was much more Western-centric and this has gradually changed.” Dalloul enrolled at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, where he studied in a studio, run by an artist, guiding Dalloul and about 19 other students. “He actually taught us to think about the relationship between shape, meaning and accessibility,” he recalls. “We have roundtables twice a week for four to five years. I think this had an impact.”

Dalloul has lived an international upbringing and journey so far, being associated with the cities of Paris, Damascus, Dubai, Tokyo and Kyoto. The artist has lived in Japan for three years, where he took up an artist residency at the French-owned Villa Kujoyama, a culturally-rich land that has clearly left its mark on his art, as well as himself. “I feel that the biggest gift that this country gave me was it allowed me to be curious again, to go to places and meet people in a way I wouldn’t have done before I travelled there. Japan has stayed with me, even when I left it,” he says, adding that he has been exhibiting work there since 2014.

In Dalloul’s intimate, two-space exhibition at Jameel Arts Centre, his first institutional show in the UAE, the viewer is invited to step inside the artist’s world of personal memories, fictional tales and empires, and observations of the world he lives in. He explores the themes of migration, personal and collective histories, as well as the concept of home. One part of the show displays his detailed pieces, aesthetically similar to comic strips and Japanese manga, whereas in the other part, Dalloul has built an invented home, decorated with old-school objects, taking the viewer back in time.

A key exhibit that is being showcased is a series of tiny drawings placed inside matchboxes, lined in an organised manner on two walls. These matchboxes, some of which can take up to two hours to complete, are something of a visual diary for the artist. “You will see across the exhibition how I really like using things from daily life. I wanted something that was familiar and everybody can use and relate to,” he explains about the chosen medium for the series.

In them, he records, with the usage of pencil and colours, scenes from daily life and world affairs, encounters with friends, portraits of political and cultural figures (such as the writer Salman Rushdie who survived a shocking stabbing attack in 2022), foreigners in Japan, protests in Syria, martyred journalists from Gaza, among many others. “These are things that are coming from the news, but also things that matter to me… They all mean something to me.”

For the decade, Dalloul has so far created 800 of them, a practice that was sparked by the long and devastating war in Syria, erupting in 2011. Initially, he started recording difficult scenes coming out of the country. “We were inundated by images coming from there,” he says. “It was hurting me and I think it was hurting everybody who was seeing it. I felt the need to draw every day.” At the exhibition, amongst the depicted figures are two small portraits of former Syrian presidents, Hafez and Bashar Al-Assad, whose 50-year regime came to an end on December 8, 2024. “My role is not to take sides. I’m just a witness,” adds Dalloul.

Although Dalloul hasn’t been to Syria since the Arab Spring, it is clearly a subject that concerns him, as seen in his art. “It was unbelievable. I spent my whole day looking at Twitter,” he says about the fall of Al-Assad. “I felt that I needed time to digest the news. There was big hope, but we are still following what’s going to happen. The hope is there; the fact that they lifted sanctions was an incredible thing. You were able to imagine that there could be a different future, which alone is worth the world.”

“Syria for me is made of stories of my first inner-circle and my family, then came friends and acquaintances,” he adds in a personal tone. “It’s fair to say that more and more over the years, Syria became a state of mind as well. But, this [his work] allowed me to keep it closer as well.”

In the exhibition, Dalloul also thoughtfully contemplates the meaning and physicality of the home, a place that is meant to shelter one from the noise of the outside world and nourish one’s wellbeing. But it can also paradoxically be a trap and limit one’s imagination if stayed inside for too long. “I think in a way, I’m obsessed with the idea of a house. Not only a house, but a household. The inner world and outside world of a house. The language used inside the house and outside the house. The way of behaving inside the house and outside the house. This house is even sometimes a country on its own, in a way,” he explains.

“I would love for the visitor to imagine that in every apartment, every city, or elsewhere, there is a world in which there is room for imagination and making your own story. Every home is worthy of being drawn, exhibited and discussed. All the persons that I have depicted or have spoken to are ordinary people, like you and me. It’s about ordinary dreams and struggles.”

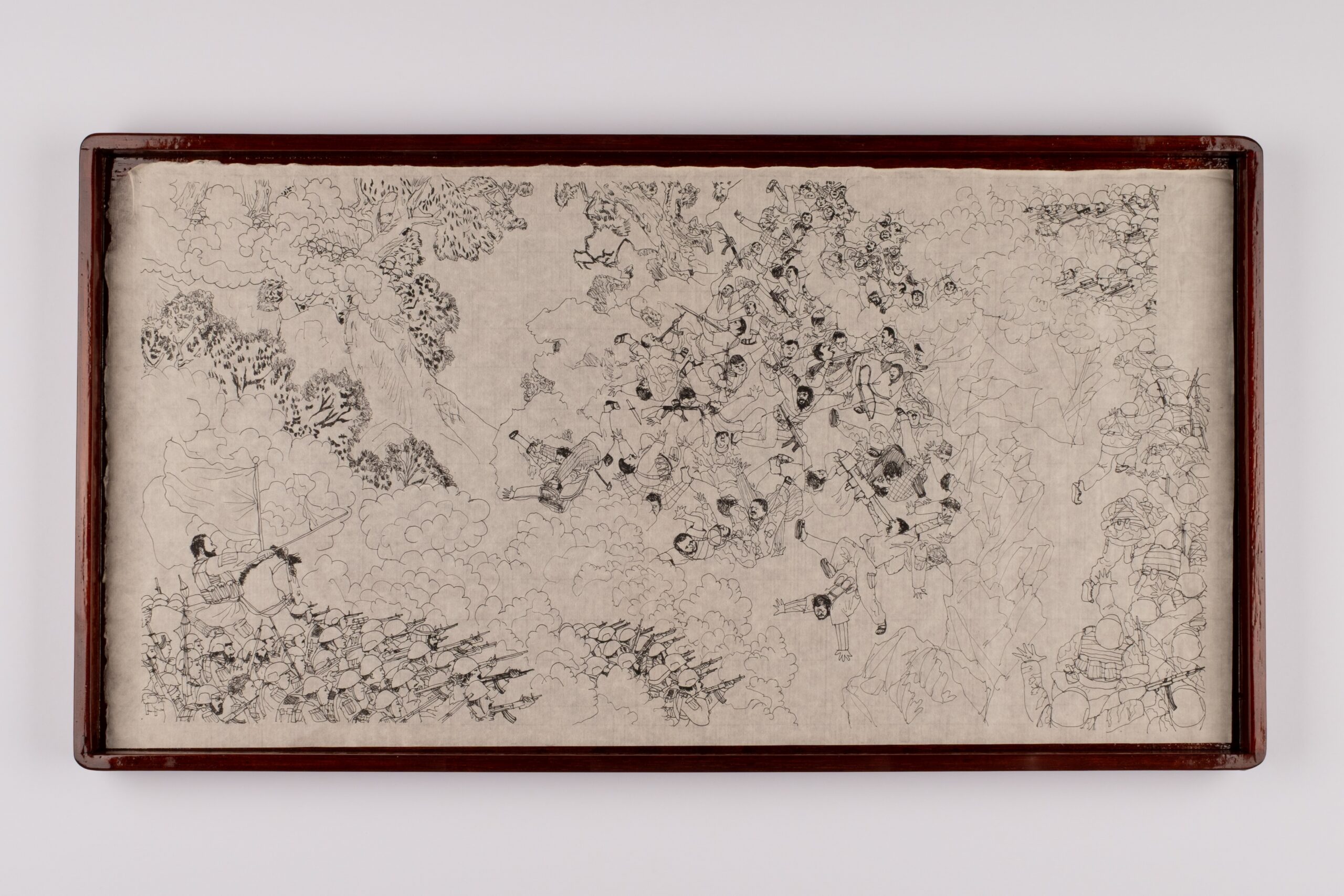

The simple home that Dalloul has created is somewhat based on his own, showcasing personal mementos, intriguing artworks and facsimiles of collage-like scrapbooks he has previously made. In one exhibit, he presents a work, entitled Eating Life (2024) where small replica teeth show scenes and objects of daily life. According to Dalloul, “black ink and patience” is what it takes to make them. In another ink-on-paper work, The War Within (2000), he depicts a grey-toned battle scene. “As you can see, it’s not an ideal world,” he comments on his creations. “It’s also made of violence, war, but also imagination. I do not want to make a perfect place. I just want to create a place where I have my own place.” In addition, he says: “I’m trying to make sense of it all: migration, identity and contemporary history.”

An old television set shows a video, Ahmad the Japanese (2021), which Dalloul created during his Kyoto residency. Through it, he delves into the lives and experiences of Syrian and Arab immigrants (both men and women) in Japan, embodied through the archetypical character of Ahmad Al-Yabani. The work is also partially inspired by a poem, entitled Ahmad Al Zaatar, written by the late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, reflecting on the theme of migration. “It’s about someone who could not be fulfilled in life. He was born in a refugee camp and has no perspective. More than 40 years after it was written, the situation hasn’t changed much. People are still born in the Levant without a perspective, and the only perspective is migration,” explains Dalloul.

The exhibition is named after a small yet central displayed artwork, where Dalloul depicts himself with a blue cat (an animal which he is allergic to) during his time in Japan. While discussing his self-portrait, Dalloul mentions The Blue Light, a book by the Palestinian author Hussein Barghouthi, whose story resonated with the artist. “He was talking about his migration to the US and how he was roaming at night, feeling estranged and alienated, and remembering scenes from his past life and childhood. Our stories are completely different but there is this idea of remembering scenes from elsewhere when you are somewhere and how some things make sense or don’t make sense at all. So, I did it my way,” he says of the painting, featuring other components such as scenes of Tokyo, geometrical patterns and battle images.

As we reach the end of our conversation, we take a seat in the ‘bedroom’ of his home, where I continue to absorb the quiet world he has expansively imagined and carefully created. I ask him if he would like to contribute to a small notebook I have been carrying around since last summer, where I have been asking predominantly regional artists to jot down their personal messages to the world – be it about life, art, creativity or anything that comes to mind. Dalloul takes a black marker and quietly draws an image of his exhibition, accompanied by three simple, metaphysical words that adequately sum up his practice: “Being somewhere else.”

![]()