News

There’s a moment in Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence where he observes that the museum craze in the West had inspired the insecure rich of his country to build replica museums of modern art, complete with adjoining restaurants and imitations of Western taste, despite, as he provocatively puts it, having “no culture, no taste, and no talent in the art of painting.” He insisted that what Turks, and people in general, should see in their museums is not imported fantasies, but their own lives.

This critique introduces Archives, Museums, and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World, a trailblazing first-of-its-kind academic venture into the region’s collecting practices, where editors John Pedro Schwartz and Sonja Mejcher-Atassi utilise Pamuk’s words to frame a broader interrogation of the region’s cultural memory. In their introduction, they zone in on Pamuk’s condemnation of museums that showcase “occidentalist fantasies of our rich” instead of lived, local life, which sets the book’s scholarly direction. Their point of view is clear: our institutions too often speak in borrowed tongues, curating someone else’s vision of culture while overlooking our own. Instead, they suggest that a local-historical approach to collecting is not to display a self-orientalising monolithic national identity. It’s to display the plurality of “our lives.”

Archiving in the Arab world has long been riddled with a complex interplay of political instability, institutional neglect, and colonial inheritance. Many national archives are inaccessible, fragmented, or quite simply non-existent. Researchers are frequently met with labyrinthine approval processes and restricted access. Writer and historian Omnia El Shakry describes this condition as a “history without documents,” a phrase that points not only to the physical unavailability of archival material but also to the ideological gaps that fill it.

In Egypt, post-revolutionary records from the Nasser period are scattered across private hands, inaccessible public institutions, and politicised memory projects. In Iraq, the Ba’ath Party archives, which were seized during the 2003 American invasion, were relocated to facilities in Qatar and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, sparking ongoing debates around cultural property and the ethics of wartime archiving. In Lebanon, the absence of a centralised, accessible national archive documenting the Civil War has left memory suspended between rumour and testimony.

The issue raised here is not the lack of documents per se, but rather the conditions of their production, the ideologies embedded in them, and their subsequent handling. Michel Foucault’s writing is seminal in understanding the power of the archive, not as a neutral repository of truth, but as a system that defines the possibility of statements; what can be said, by whom, and under what authority. What is included in the archive? What is omitted? What is rendered unavailable? What is commissioned to begin with?

In the postcolonial Arab world, these questions are essential to grappling with archival systems as sites for information retrieval, and more importantly, sites of knowledge and discourse production.

With the turn of the century, developments in digital technologies presented a new promise of democratised memory, archives unbound by geography, open to public participation, and free from institutional gatekeeping. The digital archive appeared to offer a rupture from the limitations of the traditional, state-sanctioned archive, positioning itself as a more inclusive, horizontal space of remembering. Yet, as scholars have argued, these digital formations remain deeply entangled in existing power structures. Metadata schemas reproduce the same laws of power and order: access is shaped by platform logics, proprietary software, and algorithmic visibility, and the process of digitisation itself often privileges what is already deemed valuable by institutions.

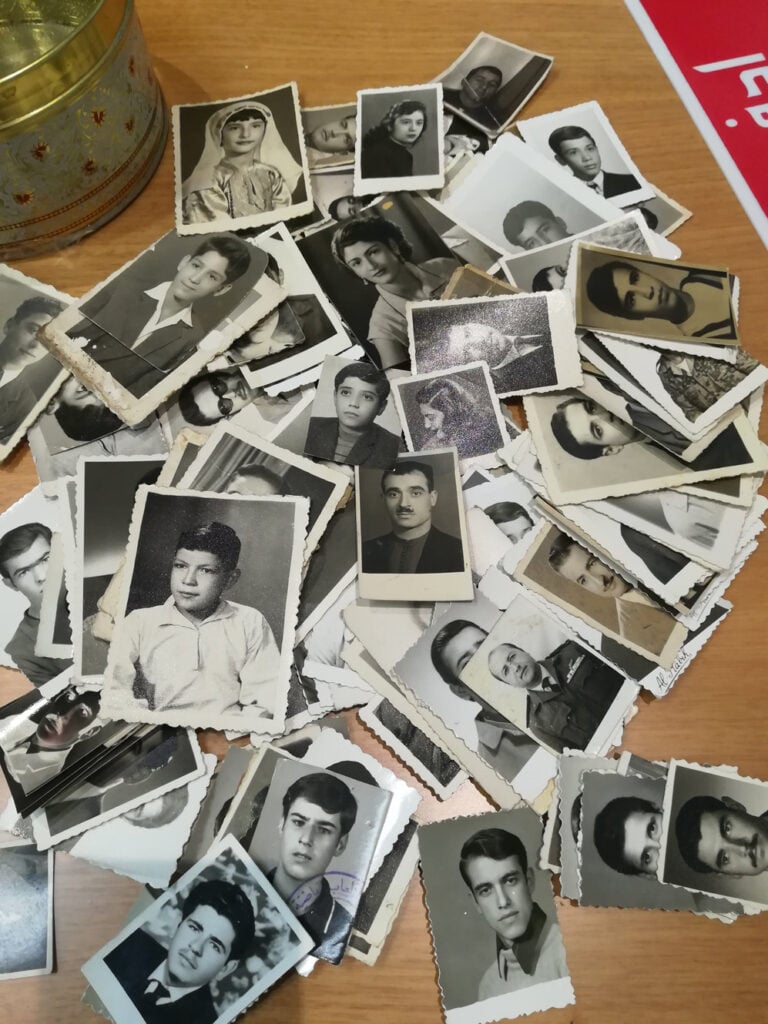

For the Arab world, this dilemma manifests clearly. Many university-hosted archives remain closed to the public. Others, like the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive, are state-funded projects, with materials in this case collected from The National Archives in the UK. The Digital Library of the Middle East, on the other hand, reproduces traditional archival authority in digital form, shaped by Euro-American archival standards and managed through institutional partnerships with the likes of Stanford University. However, there are efforts to shift this dynamic. NYU Abu Dhabi’s Akkasah Photography Archive makes a third of its holdings accessible digitally without requiring institutional affiliation—a rare exception. The archive’s approach is also quite different, highlighting a plurality in its collection through sourcing materials from family albums, studio portraits, personal collections, and vernacular photography across the “Middle East and North Africa.” This plurality of sources allows for a mosaic of visual histories that challenge monolithic national or state narratives.

More grassroots archival ventures present compelling digital, non-governmental sites of memory-making. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, for example, seeks to reassemble dispersed histories by digitising documents, photographs, and oral testimonies from across the diaspora. Yet even this effort depends on partnerships with Western institutions and digital infrastructures. And so, the Foucauldian questions remain.

The Syrian Archive offers a grassroots model of digital archiving that presents a bottom-up digital record of the Syrian Civil War by collecting citizen-shot footage of human rights violations. It is grounded in activist networks, but also relies on institutional collaborations and international partnerships with the likes of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch to ensure preservation and legal credibility. However, its visibility remains precarious and dependent on commercial platforms that routinely remove the same content it seeks to preserve. In contrast, Egypt’s 858 archive offers a much more radical alternative: a fully decentralised, uncurated, and searchable video repository from the 2011 Arab Spring uprising, organised not by categories but by timestamp. The power of this archive rests in its resistance to institutional framing altogether, embracing a raw and open-ended approach to archiving protest. Of course, this approach is not without challenges, but as far as showing “our lives,” the “858 archive” is an exemplary case study. Recognising that no single archive holds ultimate authority reframes the archive not as a source of truth, but as a construct shaped by power that must be studied as a subject in its own right.

This essay doesn’t focus on classifying archives by content, such as art, political, or personal. That choice is not due to irrelevance, but because the real stakes lie less in what an archive holds and more in how it comes into being. The discussion of the Egyptian revolution archive aligns with the ideas laid out in Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom by Abigail De Kosnik. In the book, De Kosnik defines rogue archives as collections built and sustained outside official institutions, often by amateurs, fans, and volunteers driven not by bureaucratic mandates but by passion, care, and a will to remember otherwise. These archives exist entirely online, accessible at any time, with no barriers to entry, no fees, and no concern for copyright law. Their contents have never been, and likely will never be, accepted into formal memory institutions. While De Kosnik’s focus is on fan culture, her framework is highly relevant in the Arab context. The rogue archive carries an anticanonical ethos, challenging elite forms of cultural memory, and makes space for what she calls “millions of canons-of-one.” It echoes the individualised modes of archiving that Foucault described as “emerging” in the seventeenth century.

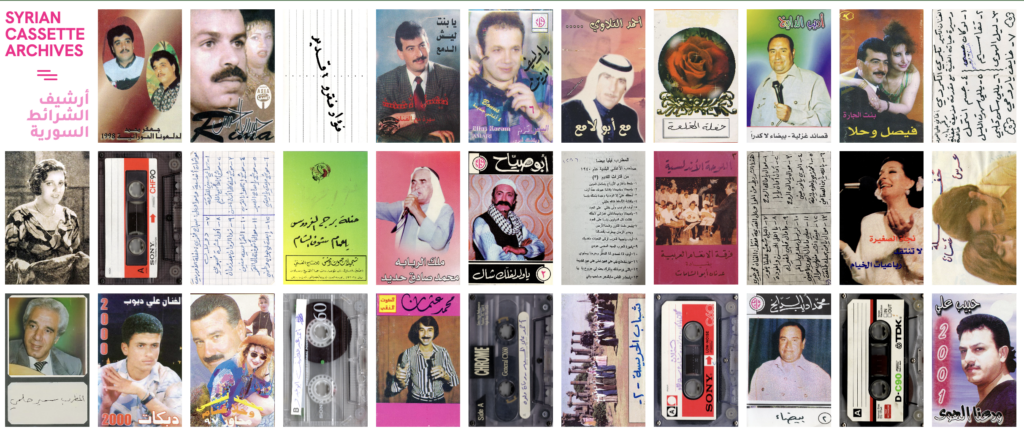

Examples on this front are many. The Syrian Cassette Archive, the Palestinian Sound Archive under the Majazz Project, and the Arabic Design Archive exemplify the shift toward personal and private archives being digitised for public access. The Syrian Cassette Archive, founded by Mark Gergis, documents Syria’s vibrant cassette-era soundscape from the 1980s through the early 2000s. It focuses on genres like dabke, folk, and shaabi that circulated through informal markets and diaspora networks. The archive draws from personal collections, street vendors, and overlooked recordings, preserving the sonic memories of pre-war Syria that are rarely captured in institutional collections. Each tape is digitised and presented with translations and contextual notes.

Similarly, the Palestinian Sound Archive, part of the Majazz Project, brings together scattered audio recordings, including studio sessions, field recordings, and family-held tapes. Much of this material has been endangered by displacement and occupation. The project revives and reclaims Palestinian sonic heritage, treating sound both as cultural memory and an essential component of resistance against an occupation whose raison d’être is the erasure of Palestinian history and heritage. The Arabic Design Archive is one of the region’s most successful community-led archival projects. It focuses on visual culture and design, collecting items like posters, book covers, advertisements, and logos from across the Arab world. Many of these materials come from personal collections and everyday street design. By digitising and organising this content through collaborative labour across Egypt, Palestine, Morocco, Lebanon, Canada, and the UK, the archive helps uncover overlooked histories of Arab graphic design, a field that has received little academic attention, and offers an alternative to official, state-approved visual history.

This growing movement toward intimate, self-directed forms of archiving is powerfully embodied in the work of Jasmine Soliman and Hind Mezaina, co-founders of Collected Histories. Their project is dedicated to preserving oral narratives and personal memory. Through public workshops, film screenings, and object-based discussions, they invite participants to become “citizen archivists.” Attendees are encouraged to bring personal or family objects, share their stories, interrogate their origins and history, and explore what those items might contribute to a community archive.

Soliman and Mezaina, along with archivist Jon Burr, also guide participants in publishing their archival materials to the Internet Archive, a free and open platform that democratises digital preservation. Both practitioners come from a long line of citizen archiving practices. Soliman’s approach builds on her earlier work with the previously mentioned Akkasah Photography Archive, where she managed major vernacular collections. Mezaina, an artist, writer, and film curator based in Dubai, has long chronicled cultural and urban life in the UAE through her photography and projects like The Culturist blog and The Culturist Film Club.

Citizen rogue archiving has found a particularly resonant space on social media, especially Instagram, where individuals across the Arab world are documenting memory on their own terms without formal or institutional knowledge of archiving. In contexts where access to national archives is restricted or where official heritage institutions fail to reflect the diversity of local and regional histories, Instagram has emerged as an accessible and intuitive space for personal and collective archiving. These accounts often function as dynamic visual repositories, combining photographs with storytelling, commentary, and communal memory work. As scholar Sumayya Ahmed notes in Documenting Doha: Community Archiving and Collective Memory in Qatar, these practices often emerge in response to the erasure or flattening of local identity within formal heritage institutions. These rogue digital archives may lack institutional structure, but they are rich and timely, offering an affirmation of sentimental and important local memory that is largely absent from the traditional archive.

“Social media projects play an important role in driving interest and creating community around heritage and collective memory. In the last 10 years, there has been an increasing interest in archiving and in the ability to ‘look back,’ perhaps in part due to our increasing reliance on all things digital. We no longer retain much ephemera, the traditionally paper-based objects that indirectly record our lives; cinema or train tickets, hotel receipts, event flyers,” Collected Histories’ Soliman tells ICON MENA. “Much of Gen Z may not own a printed photograph. Sumayya Ahmed refers to photo-based social media projects as allowing ‘people to inventory those very absences.’ Although they lack the permanence and sustainability to be described as an archive, they are increasingly an immediate and democratised way of spotlighting underdocumented communities and time periods; they provide an access point to the heritages that many institutions aren’t interested in collecting or that society wants us to forget.”

Calling a social media feed an archive might be a contradiction in terms, but these repositories are doing the work. They’re instant, unorganised (and unsearchable), instantly shareable, and everywhere. If collective memory did not have a place in “our lives” before, it has found one now, even if it’s just drifting through a passive scroll. That’s not to erase the early internet forums that shaped digital culture across the Arab world, which merits a whole investigation on its own, but Instagram’s infrastructure has pushed a more visible, semi-archival practice into the spotlight.

Unlike the previously mentioned archives, like the Syrian Cassette Archives and Arabic Design Archive, which are physical archives that have been digitised and promoted through social media, these rogue archives are digital-first, or rather, Instagram-first. Cheb Gado (@cheb.gado10) has amassed over 32,000 followers through curating and sharing timely work from across the region. The archive jumps back and forth between different timelines and geographies, from resistance imagery in the West Bank to tributes marking the recent death of Lebanese music and theatre giant Ziad Rahbani.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DGDstEhtgXq/?img_index=1

Ahmed Gado grew up between Egypt and Kuwait in the 1990s, in a home shaped by heritage, movement, and a strong exposure to Arab arts and cinema. His father, who worked in Kuwait, would bring home VHS tapes of old Arabic films, which became an early source of visual influence. This interest expanded through the music of artists like Fairuz, Ziad Rahbani, George Wassouf, and later Rachid Taha, shaping a deep engagement with themes of identity, exile, and memory. His current practice focuses on building a contemporary Arab archive that pushes and pulls between personal and collective memory, “something that comes from the heart and speaks to others,” aiming to document the emotional and cultural experiences of his generation across the Arab world.

He plays the curator/rogue archivist role, pulling from a mix of different platforms, like Getty Images, Flickr, Instagram, torrent archives, and personal digital collections. “Through sharing Arab stories and deeply human experiences, I try to draw an emotional map that binds us together beyond political and geographical borders,” Gado tells ICON MENA. “But at the same time, there’s something powerful in this informality. These archives aren’t institutional. They’re often deeply rooted in lived experience. They create a space where we can reclaim memory, especially in regions where official histories are incomplete, silenced, or manipulated… Still, the limitations are real. Instagram isn’t built for preservation. It’s built for consumption. That’s why I try to treat what I share as an invitation, not a final destination. The real archive, in a way, is the conversation that follows.”

“The real archive, in a way, is the conversation that follows.”

This logic mirrors the structure of the internet itself. Social media is not designed to preserve, but to present material for consumption. The (rogue) archive, in this context, becomes less about storing the past and more about responding to the present by pulling from the past. Posts are created, shared, and circulated in tandem with current events, uprisings, anniversaries, deaths, and disappearances. Relevance becomes the trigger, and in a way, turns the archive into a more pertinent tool for eliciting remembrance. The archive surfaces when it is needed, not when it is necessarily searched for. Gado’s approach reflects this shift. What is archived, in real-time, is not just what once was, but what now matters. Memory here is not static, but recirculated and inserted into ongoing conversations. It’s not a system built for stability, but it allows for mass reach, and mass access, which becomes the starting point of the archive’s development, not an afterthought.

Another powerful feature of these archives is their interactivity, not through their search and categorisation features (which are nonexistent), but through the interaction that users have. The archive then also becomes a site for discussion and the negotiation of meaning. Dance Archivist (@dance_archivist) spotlights the legacy and history of dance (specifically Raqs Sharqi, among others) in the broader region. They source material from a wide range of places, primarily by uncovering existing footage from films, TV shows, personal videos, and family archives. They edit and contextualise these clips, often connecting them to other media like vintage entertainment magazines or related footage to reveal new links. Additional sources include fellow archivists across Lebanon and the region, who share items like photos, VHS tapes, posters, and magazines. They also source materials from markets and shops, and through personal networks or public calls for submissions.

The participatory nature of the archive plays a key role in its relevance. In a recurring series on dancers from Lebanon’s pre-war era, the archivist pieces together material from filmed performances to vintage entertainment magazines in a Carousel format. These fragments are combined with researched captions and accompanying text to build a fuller picture of each dancer’s experience and legacy. The posts act as open invitations for collective memory work.

“What I find interesting about the social media archive is the co-creation of memories and narratives,” the archivist tells ICON MENA. “Sometimes I post a video without knowing who the dancer is, and someone in the comments, often from an older generation, recognises them, remembers the performance, or even attended the show. They fill in the gaps.” In this way, the archive is shaped not only by its contents but by who engages with it. A fully realised breathing and living resource that makes us feel things, connects us to community, and engages us in different ways. And, most importantly, grows through exchange and participation.

Long story, very short: No, the rogue social media archive cannot replace the traditional archive. But it opens the door, albeit in reverse, to a more radical idea of what the archive could be. It allows us to unlearn our assumptions about what memory should look like, how it should behave, and who gets to handle it, ultimately to be able to build and manage collective memory differently. Through screenshots. Through comments. Through shaky videos and disappearing posts. Through enduring ephemera. Social media archives may not offer long-term preservation or informational accuracy, and for them to be living archives, they must risk the possibility of disappearing at any given moment through a deleted account, a platform shutdown, or a change in terms and conditions. So the sword is double-edged, by all means. But they offer something else: immediacy, access, friction, and the potential to shift who gets to remember out loud.