News

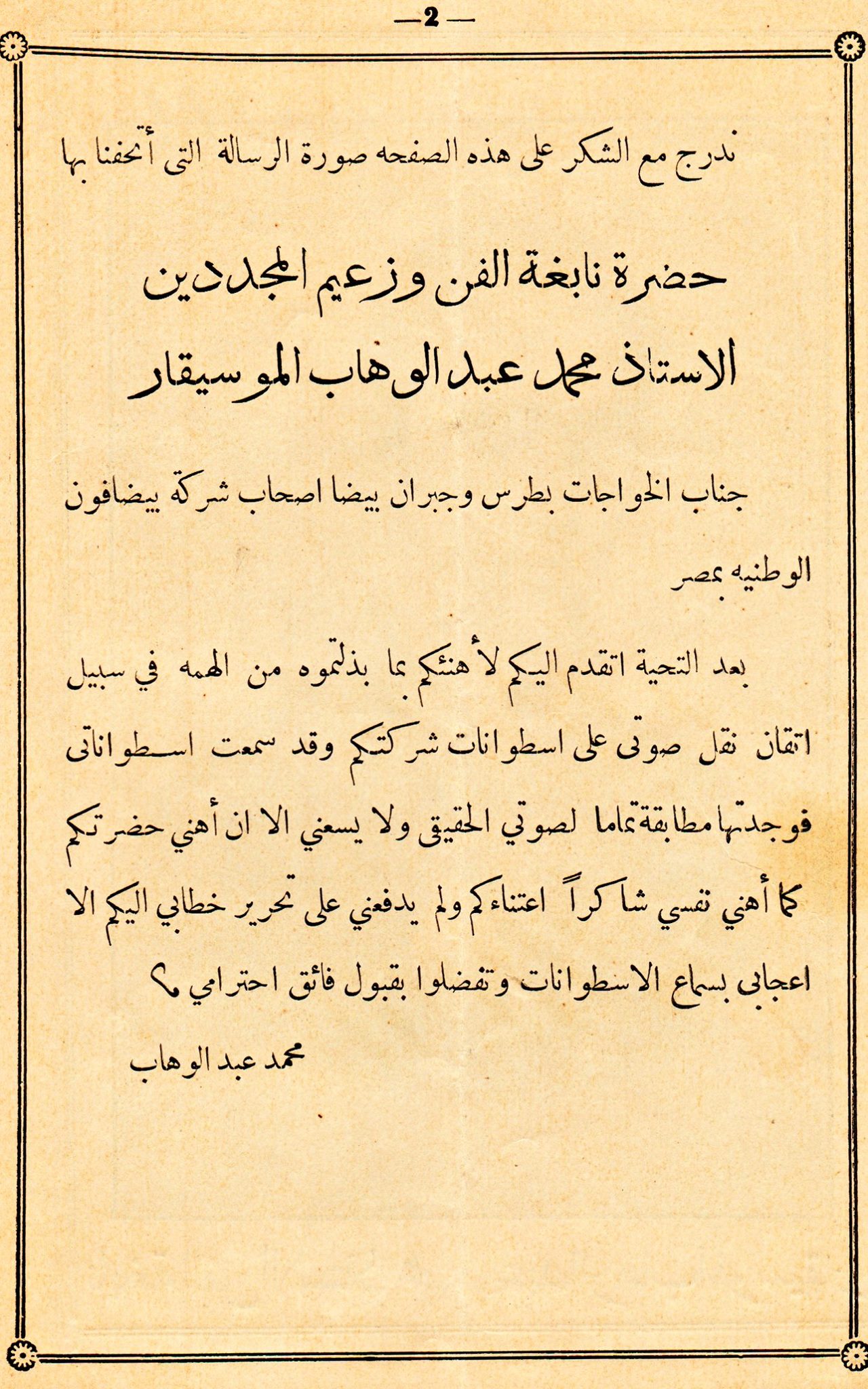

“I write to congratulate you for the great effort you have shown in perfecting the recording of my voice on your company’s records,” penned the legendary Egyptian singer and composer Muhammed Abdel Wahab in 1930 to Jibran and Boutros Baida, the visionary brothers behind Baidaphone, the first Arab indie music label.

Echoing this admiration, Tunisian chanteuse Habiba Msika wrote on April 21, 1928, expressing her gratitude for “the good electronic recording of [her] Arabic records.”

Such letters underscore just how rare and revolutionary high-fidelity recordings were in the region at the time. For artists like Abdel Wahab and Msika, hearing their own voices captured with clarity was a novel and exhilarating experience. That an Arab-owned label could achieve such technical mastery was, in its day, worthy of admiration. At that time, many Arab musicians had relied on travelling abroad or working with visiting European companies, most famously the Gramophone Company, to record their music.

Often called HMV, the Gramophone Company became known for its motto ‘His Master’s Voice’ and its logo featuring a dog listening to a gramophone. They operated on a global scale, sending engineers with portable recording equipment around the world to capture local voices and sounds. These recordings were shipped back to central factories in Europe, pressed onto discs, and then distributed to stores worldwide.

It was through this emerging system that Arab voices first encountered the modern recording industry. Umm Kulthum, for instance, had some of the earliest songs of her career captured in these sessions in 1924, beginning with the poem Al-Sabbu Tafdahuhu Uyunuh (The Eyes Betray the Lover).

Since opening its permanent branch in Cairo in 1903, the Gramophone Company had leveraged a large and eager audience, a flourishing musical scene, and the advantages afforded by strong British colonial ties, dominating the region’s recording business.

The idea of recorded music spread quickly across the Arab world. For the first time, songs could leave the stage and enter people’s homes, turning fleeting experiences into something lasting, something you could return to. Shortly after, other Western record companies soon joined the race. The German label Odeon was among the first to establish a strong presence in Egypt, followed by American Columbia Records, which quickly expanded into Arabic repertoire. Another German company, Beka, produced some of the earliest Arabic recordings before fading from the scene, while the French Pathé built a strong base in North Africa. The market was saturated. Everyone was competing to capture the sound of the Arab world.

But it wasn’t only foreign companies that saw the opportunity. A Lebanese family believed Arabic music deserved a company of its own—one rooted in the region and made for its people. With that vision, they set out to establish a label capable of capturing both local and regional audiences, with headquarters in the heart of Berlin, near the Brandenburg Gate.

Baidaphone was founded around 1906 by five members of the Baida family, Michel Baida, his brothers Jibran and Boutros, and two cousins, who partnered with a German manufacturer to produce records. They soon opened a modest record shop in downtown Beirut and began documenting local talent, aided by European engineers who made regular trips to the region.

The company later expanded to Cairo, quickly cementing its status as a major player in the burgeoning record business. By recording the voices of Egypt’s foremost stars, like Sayed Darwish, the revolutionary composer, and Mounira al-Mahdiyya, a diva of her era, Baidaphone helped define a golden age of Arab music on record.

Unlike the British HMV, Baidaphone was run by Arabs, for Arabs, carrying a strong sense of cultural identity. Its iconic logo, a running deer, quickly became a recognisable symbol across the Arab world.

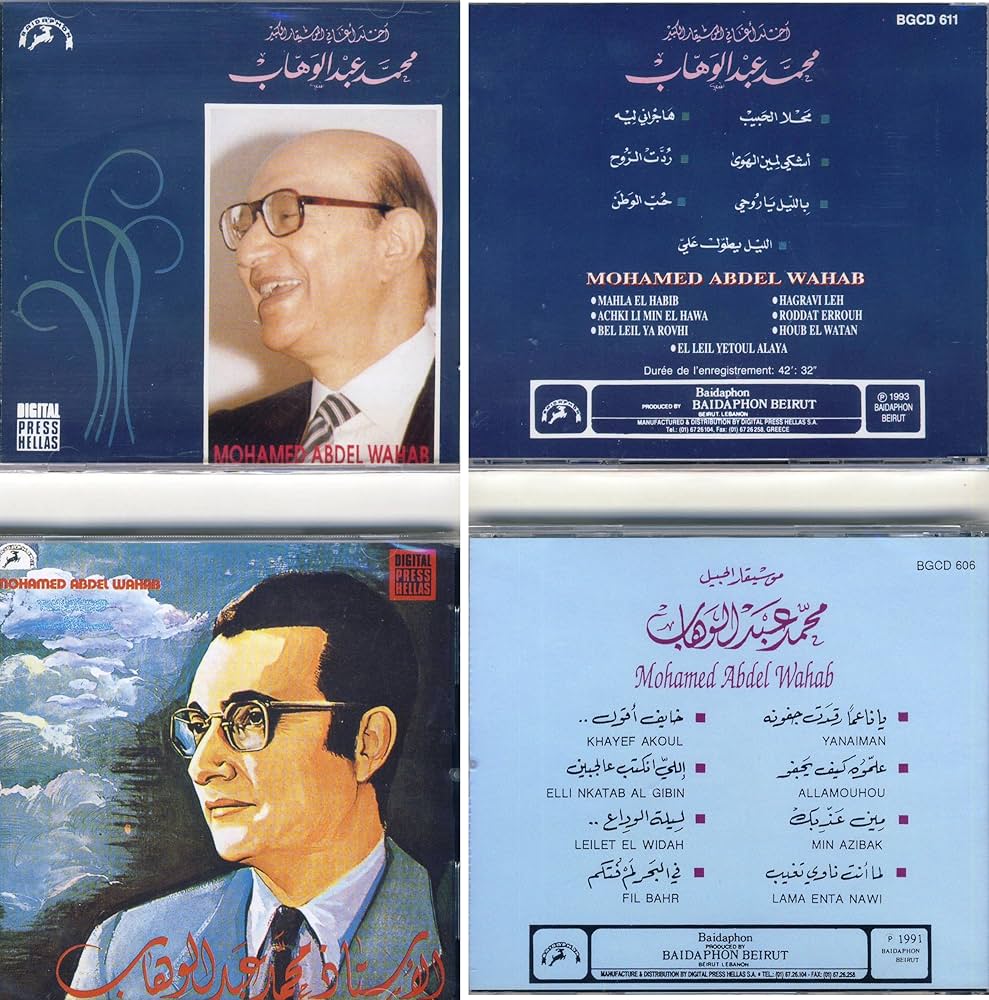

By the 1920s, Egypt was home to two rising musical titans: Umm Kulthum and Mohamed Abdel Wahab. While Umm Kulthum often recorded with foreign-owned, well-established labels, Baidaphone took a bold, distinctly local approach. They struck a partnership with Abdel Wahab, one of the earliest examples of a long-term artist–label agreement in the Arab world.

Through this collaboration, Abdel Wahab’s fame spread rapidly across Egypt and the wider region, and with it, Baidaphone’s reputation grew, cementing its place at the heart of the industry. The Baida family went a step further than their foreign counterparts, printing singers’ portraits directly on the records. A simple yet striking innovation that reflected their forward-thinking approach to marketing and branding.

In 1933, he starred in Al-Warda al-Bayda (The White Rose), his first film, and the first true Egyptian musical as well as a landmark in Arab cinema. Baidaphone seized the opportunity, becoming the first record label in the region to venture into film production. By backing the movie and recording its songs, they opened the door to a new era where cinema and records would thrive together. Cinema lifted Abdel Wahab to a new level of stardom, giving him access to audiences far beyond the concert hall, and Baidaphone strategically aligned itself with this shift.

Baidaphone’s ambitious strategy didn’t end with Abdel Wahab. In the 1930s, the company expanded its roster to include another pair of rising stars, the siblings Farid al-Atrash and Asmahan. Both were exceptionally talented musicians descended from the royal al-Atrash family, who had relocated from Syria to Cairo as political refugees.

When Farid al-Atrash and his sister Asmahan arrived in Cairo in the early 1930s, Baidaphone became their musical home. The label offered Farid his first real platform, where he began shaping his signature style as a composer and oud player, blending his talents with Egypt’s modern sound. As for Asmahan, her relationship with Baidaphone was unlike any other. Some accounts suggest that after she gave up singing following her marriage, she happened to meet Michel Baida, one of the company’s founders. In Damascus, during their meeting, he urged her not to let her musical gift go to waste. Bolstered by his encouragement, Asmahan returned to the studio, and under Baidaphone, she recorded a string of hits that would establish her as a formidable rival to Umm Kulthum.

In the 1930s, French colonial authorities in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco grew wary of Baidaphone’s patriotic repertoire, especially that of Habiba Msika, going so far as to ban the label’s records within their territories. Michel Baida was even accused of collaborating with the Germans to undermine French authority in the region. Despite these restrictions, the music found its way to listeners through clever relabeling and the label’s branches in Casablanca, Jaffa, Baghdad, and Beirut, ensuring that Baidaphone’s influence continued to expand across the Arab world.

By the 1940s, the landscape of Egypt’s music scene was shifting rapidly. World War II disrupted global trade, making it harder to import materials and press new records, while the European engineers and companies that had once dominated the market were forced to scale back. At the same time, a surge of Egyptian nationalism was reshaping cultural tastes, and audiences increasingly demanded local voices, local stories, and local ownership.

It was in this turbulent climate that Baidaphone underwent a profound transformation. After rising tensions within the company, Mohamed Abdel Wahab persuaded many shareholders in the Egyptian branch to sell their stakes, giving him unprecedented artistic and financial control. The Baida family rebranded the company as Cairophone, signalling a symbolic shift from a label with European roots to one proudly Egyptian. For many foreign record companies, the golden years were fading, but for Cairophone, a new era was just beginning.

Under its new identity, Cairophone honed its focus on Egyptian talent and audiences. Abdel Wahab introduced fresh voices to the scene, including a young singer who would become a legend: Abdel Halim Hafez. From the 1940s through the mid-1950s, Cairophone dominated the Egyptian record industry, guided by Abdel Wahab’s artistic vision.

The legacy of the Baida family endured long after. Until the early 1990s, Michel’s nephew Bernard Baida continued distributing the music of these iconic stars, pressing records in Greece due to Lebanon’s civil war. After him, no family member carried on the label with the leaping gazelle. Yet the impact of Baidaphone, and later Cairophone, on Arabic music is undeniable. From Umm Kulthum to Asmahan to Abdel Halim Hafez, the sound of the Arab world would not have been the same without it. And even if the gazelle no longer leaps, it’s forever turning.

The company included this letter in one of the record catalogues it published in 1930.

Courtesy of AMAR (Foundation for Arab Music Archiving & Research)