News

“Tout ce qu’il faut pour faire un film, c’est une fille et un flingue.”

“All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun,” legendary filmmaker and French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard once said. Echoing American director D.W. Griffith, this enduring quote, delivered firmly tongue-in-cheek by Godard, was part critique, part commentary on the seductive power of visual storytelling. It cut to the heart of one of cinema’s oldest tricks: aestheticising violence. Strip away context, critique, or historical truth; as long as there’s a girl and a gun (or, even better, a girl with a gun), you’re halfway to a spectacle that audiences will buy into—a spectacle in which they’ll root for the soldier, cry for his loss, and walk away feeling something, even if they’ve seen nothing at all.

It’s fitting, then, that A24’s new war film Warfare—picturesque and technically immaculate—opens with a group of US Navy SEALs, guns in hand, huddled around a TV a long way from home, in Iraq. On-screen plays a grainy 1980s-style music video for the song Call on Me: women in pastel leotards pump and thrust their way through a leering, libidinal lens—all sweat, skin, and lingering eye contact. Girls and guns.

This moment, drawn from the real-life deployment of co-director and former soldier Ray Mendoza and heralded by critics and audiences alike, is cinematic cliché: American soldiers, stranded in hostile terrain, starved for sex and reminders of home. It’s a scene we’ve seen plenty of times before. In Francis Ford Coppola’s towering war epic Apocalypse Now, Playboy bunnies are flown into Vietnam to entertain troops, sparking a frenzy of lust, loneliness, and violent masculinity. In The Thin Red Line, memory becomes an erotic refuge, with one soldier repeatedly flashing back to his wife’s body in a bath. The examples are endless.

Like The Thin Red Line and Apocalypse Now, Warfare has also been acclaimed as an urgent “anti-war” film since it premiered in April. And these films are not unique in that regard. War stories rarely frame themselves as pro-war unless, of course, there’s a bald, muscular demi-human with a thick Russian accent, or a feeble, bearded Brown man in a turban involved. Instead, war films generally centre on brutality and trauma, using agonising visuals and intimate camerawork to craft what appears to be a critical message. Warfare follows in that tradition. But its critique is selective. The horrors it foregrounds are those endured by Mendoza and his fellow soldiers when a surveillance mission inside an Iraqi home goes wrong. It extends empathy to the invaders, not the invaded. To the agents of empire, not its victims. It is not isolated in this regard, either.

As a child of empire and imperialism, who also happens to be a massive movie buff, seeing Warfare employ the same hackneyed storytelling techniques that Hollywood’s blockbusters have done for decades saddened me. Perhaps naively, I expected that A24, an independent art-house studio esteemed for telling unconventional and diaspora stories, would not produce a film substantively indistinguishable from a Warner Bros production. It has also made me think about the “war movie” more generally. Can a war film truly be anti-war if it refuses to acknowledge the humanity of those most harmed by war? Can it still claim that label if it’s shaped by, and indebted to, the machinery of war? Or, simply: can a war film ever really be anti-war?

The ‘anti-war film’ tag gets tossed around with such ease that it’s become difficult to take it seriously. Directors invoke it in interviews, critics uncritically use it in reviews, as if portraying trauma and chaos automatically equates to a condemnation of war. But as Guy Westwell, film historian and author of War Cinema: Hollywood on the Front Line, argues: “Films that represent war are always compromised by the aesthetic and narrative demands of popular cinema.” That is where the ‘anti-war’ label starts to unravel, because showing war’s horrors isn’t the same as interrogating the systems that underpin it.

Most “anti-war” films don’t end up challenging militarism or empire. They don’t indict the nation-state or the war machine. Instead, they centre the pain of the soldier, frame it as noble suffering, and drape it in the aesthetic codes of cinematic beauty. Warm light over cold bodies, hyperreal sound design, drone shots of desert terrain set to ambient melancholy. Every cent of a multi-million dollar budget goes into capturing the barbaric realities of armed conflict. The issue isn’t that these films are well-made. It is that they are often too well-made, so immersive, so charged that they end up beautifying the very thing they claim to condemn. The pornography of pain. As Susan Sontag put it in Regarding the Pain of Others: “There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera.” When war becomes a site of cinematic pleasure, the violence needs to slip into something palatable: individual stories of bravery in which the politics are obfuscated, if not outright misrepresented or disregarded.

In this schema, the protagonist is usually the anti-hero white soldier, a victim of fate. Journalist David Sirota writes in his book Back to Our Future: “The Reagan-era shift in pop culture rehabilitated militarism by painting it as reluctant heroism; a necessary evil carried out by emotionally complex white men.” War becomes a theatre of bravery, not a political project with perpetrators and victims. The result is a cinematic tradition that mourns war without ever questioning who it serves and who it destroys. When these films go on to win awards, they become absorbed into national mythologies (Kathryn Bigelow famously became the first woman to win Best Director at the Oscars for The Hurt Locker). They become sanitised memories of ‘what really happened’. They flatter those who wage war, and remain silent on those who suffer most.

This is where Warfare slips in, and not despite its indie pedigree, but because of it. As an A24 production, Warfare comes with the sheen of credibility. Known for its offbeat, auteur-driven storytelling, A24 might just be the only studio beloved by cinephiles, critics, and casual audiences alike. Unlike US Department of Defense-stamped movies like Top Gun or Zero Dark Thirty, A24 is the last place you expect to find uncritical militarism. And so, when Warfare centres its narrative on a group of invading American soldiers, giving them backstories, inner lives, and gritty trauma, it doesn’t read as propaganda. It reads as prestige cinema. But just because it is indie doesn’t mean it resists ideology. In fact, it might be more dangerous for exactly that reason. But that is not the way it needs to be.

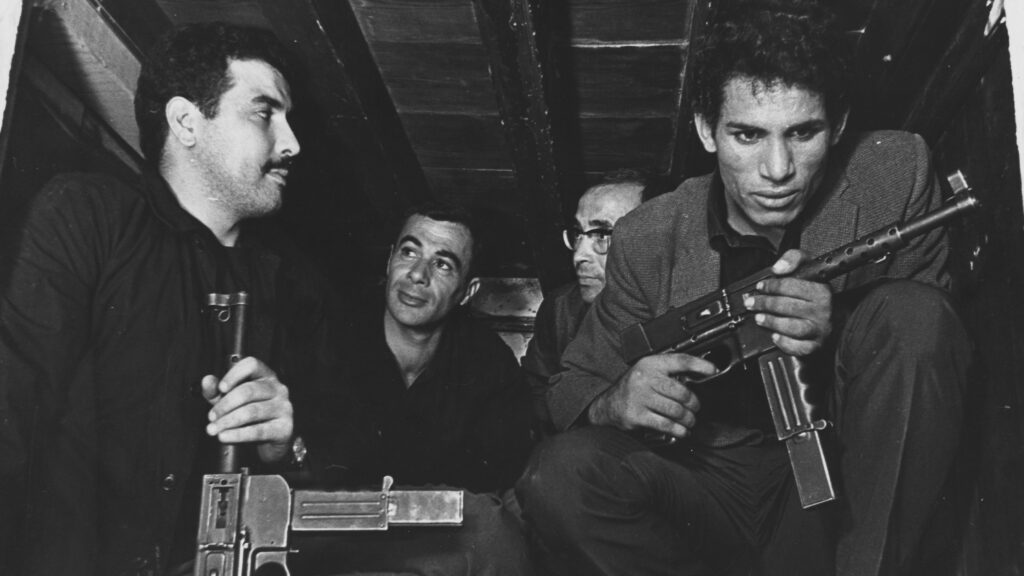

Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 classic The Battle of Algiers chronicles Algeria’s anti-colonial revolt against French occupation. It is brutal, unsentimental, and intentionally de-glamourised. The camera doesn’t linger on bloodied bodies. Instead, it captures the daily humiliations of life under occupation; the checkpoints, the curfews, the racialised policing. French paratroopers are not given tortured backstories or tearful confessions. They are agents of the state, carrying out state violence. What makes The Battle of Algiers enduring is its clarity—its refusal to rationalise or obfuscate colonialism.

Similarly, Come and See, Elem Klimov’s masterwork about Nazi atrocities in Belarus, is often cited as the best war film ever made. But what makes it “anti-war” isn’t just its horror but its refusal to offer catharsis. No rousing score. No redemptive arc. The camera stays close to a young boy’s face as he witnesses the horror. It resists spectacle. There are no cool slow-motion hero shots, only relentless devastation. Still, there is an argument to be made that Come and See utilises the very cinematic techniques of immersion and hyper-realism that Americana cinema does. But there is a crucial difference: Klimov’s film doesn’t centre on the heroism of soldiers. It asks us to confront what war does to those who never chose to fight.

In fact, anti-war films don’t need to utilise the machinery of war at all. Grave of the Fireflies, the Studio Ghibli animated classic, follows two orphaned siblings struggling to survive in Japan during WWII. There are no soldiers in sight. Only the wreckage they leave behind. Its power lies in its intimacy. The battlefields are off-screen, but their brutal consequences are ever-present: in empty pantries, infected wounds, starvation and lost childhoods. Where Hollywood pushes trauma through testosterone and spectacle, Grave of the Fireflies collapses it into something smaller; hunger, despair, and an unbreakable sibling bond. And because it refuses to aestheticise war (no girls, no guns), it makes the devastation hit harder.

They may be stylistically contrasting, but what unites these three films is that they do not look away. They do not shift the lens onto the coloniser’s feelings or the soldier’s heartbreak. They refuse to universalise suffering or flatten power. They do not treat war as just tragedy. And crucially, they extend humanity to those who are often denied it; the civilians, the displaced, the occupied. In contrast, in many Western (anti) war films, Arabs are either targets or terrain. They scream, run, explode. They are framed through the rifle scope, the drone screen, and the soldier’s PTSD, but are rarely ever offered agency (unless they’re collaborating with the US war machine).

To me, a truly anti-war film resists this flattening. It is not about proclaiming “war is bad” but centring the oppressed, the occupied. An anti-war movie disorients and implicates. It tells the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it might be. An anti-war movie might even be cinematically beautiful, but it is not the violence or long-take wide-shots that makes it beautiful.

It might, therefore, even be tempting to say that a truly anti-war film cannot come from the West. You only need to point to the war stories that have won Oscars in recent years when making this argument. The Hurt Locker, heralded as a psychological character study of addiction to war, ends up mythologising it instead. American Sniper, well… when your “anti-hero” is an invading soldier killing Arab civilians, the less said about it, the better. These are supposedly complex works. But, ultimately, they recirculate the same old story: the American soldier as a haunted hero, navigating a savage world that just doesn’t understand his pain. But not every Western filmmaker buys into this fantasy.

Ken Loach, the British director known for his unwavering commitment to working-class struggle, who was expelled from the Labour Party by Keir Starmer in August 2021—a badge of honour—has long demonstrated that it is possible to make anti-imperial films within the heart of empire. His 2006 Palme d’Or-winning The Wind That Shakes the Barley is a case in point. Set during the Irish War of Independence, it doesn’t flinch in its portrayal of imperial brutality, but nor does it settle for simple victimhood. Loach’s camera is calm, almost documentarian, but his politics are not. The film recognises war not as a tragedy of good men corrupted, but as a consequence of colonial domination, class oppression, and systemic violence. The British aren’t misunderstood. They’re occupiers. The Wind That Shakes the Barley ruffled many feathers in the right-wing British tabloid press. The Daily Mail responded to Loach’s film with the headline: “Why does Ken Loach loathe his country so much?”

This kind of clarity, rare in Western cinema, is what makes Loach’s work feel dangerous to so many stenographers of imperialism. He doesn’t invite us to sympathise with the empire’s foot soldiers. He aligns his storytelling with those who resist them. This might seem like a low bar (really, it is), but in a post-colonial world still steeped in Orientalism, as Edward Said described it, that bar is seldom cleared. Western filmmakers are uniquely privileged, with access to global platforms, critical institutions, and festival circuits, to shape the conversation around war, empire, and morality. When they tell stories about the Middle East, or set their films in “hostile territories” full of Brown bodies and blurry morals, the consequences are more than just cinematic. They become part of the scaffolding that makes the dehumanisation of Arabs not just possible, but palatable. Loach shows us that it doesn’t have to be that way. That Western cinema can reckon with its imperial lineage, but it must do so from the vantage point of the oppressed, not the occupier.

If an anti-war film can truly exist, maybe it starts here: not with the aesthetics of violence or even the politics of representation, but with the ethics of solidarity. Who does the camera align with? Whose pain is made legible? And who, ultimately, is given the right to be complex, broken, and still human?

Of course, Arab filmmakers have long been trying to tell the stories that they’ve been historically denied the space to articulate. Think Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now or Omar, films that refuse to caricature the choices imposed by occupation. But these films, unlike Warfare or The Hurt Locker, aren’t absorbed into the bloodstream of cultural hegemony. They’re not reviewed as national reckonings. They’re niche, foreign, subtitled, and rarely allowed to define the genre they inhabit.

So, can anti-war films exist? Absolutely. Do anti-war films exist? Sure. There are movies that grip you and move you profusely long after the credits roll, not because they fetishise battlefields and amputations, but because they lay bare the politics and dehumanisation of war and give agency to the victims of empire. But they are rare. And they are almost never the ones that get handed Oscars, distribution deals, or Pentagon-backed praise.

What we usually get instead are the “anti-war” films that secretly adore war, that cradle the soldier, not the civilian. Films that ask us to weep for the conscience of the invader, but never to imagine what it means to be invaded. From American Sniper to Zero Dark Thirty; from tortured white guys to white girls who torture (but feel bad about it), the same story gets told: imperial violence, but with feelings. It’s the logic of war criminal and former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir: “When peace comes, we will perhaps in time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing our sons,” she famously said. “But it will be harder for us to forgive them for having forced us to kill their sons.”

And now, with Warfare, we’re meant to applaud a film where guilt passes for critique, and the invaded are footnotes. Who cares about what happens to the Iraqi family in the film, whether they die or live? Their stories are insignificant in the face of our heroic guardians of empire.

Filmmakers from the Global South have long been telling stories of occupation, resistance, and grief with clarity, courage, and complexity. Perhaps it’s time we stopped looking to the architects of empire for moral reckonings and started trusting its victims to narrate their own stories. To put the spotlight on the movies of Ousmane Sembène, of Elia Suleiman, of Annemarie Jacir. It’s time to recognise that the future of anti-war cinema lies elsewhere. Not in Hollywood’s guilt-riddled prestige dramas. Not in conventional war movies at all, but in the hands of those who have lived through what empire looks like, and survived it.

“All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” Well, what happens if you take both away? Can you still make people watch? Can you still make them care? An anti-war movie wouldn’t need to centre on the gun. It wouldn’t even need one. It would centre the people who have always lived under its shadow. It would let them speak.