News

Rowan Athale’s Giant was released early this year, in what seems to be a micro-trend of autobiographical fighting films from Sydney Sweeney’s Christy to Dwayne Johnson’s The Smashing Machine.

Starring Amir El-Masry as 90’s British-Yemeni boxer Naseem “Prince Naz” Hamed, the film follows Naz’s journey to becoming World Champion and his turbulent relationship with his trainer Brendan Ingle, played by Pierce Brosnan.

Despite his pride in his Yemeni roots, Naz occasionally leaned into orientalist spectacle, flying into matches on a “magic carpet” to meet the expectations of a predominantly Western audience. Aware of it, or not, he entertained the West’s perception of Arab men, popularised by American media like Disney’s Aladdin (1992), which was released in the same year as his professional debut at the age of 18.

It’s unclear whether Naz’s stunt was an attempt at reclamation or an appeal to Western media. Regardless, decades later, he remains a pioneer in Arabian boxing, with a 36–1 record and 32 knockouts, even declaring himself “Public Yemeni Number One” in a 2018 interview. The biopic enters a discussion regarding the representation of athletes, not as an obstacle in sport but rather as a coexisting challenge, despite unmistakable talent.

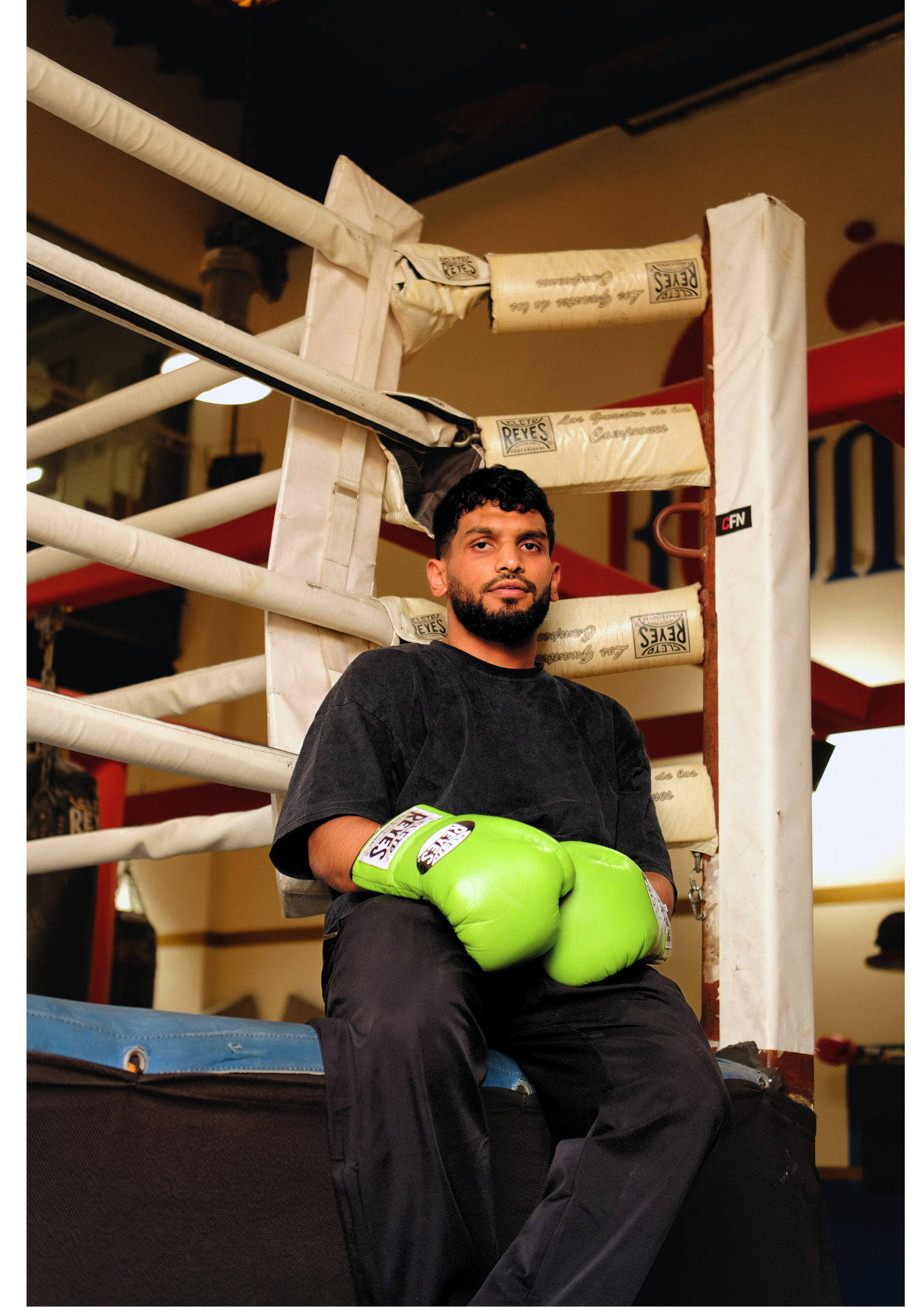

The weight of representation is heavy, carried through generations and upheld today by boxers such as Faizan Anwar, who tells ICON MENA, “[Our Western opponents] don’t have to think, ‘Oh, there’s a nation behind me.’” The WBA champion belt holder, with a 21-0 record, opens up about his experience as an Indian fighter competing in a western-dominated sport. As his ranking in boxing continues to rise, more eyes turn towards him, and in turn, more opinions: “When I am at a press conference or inside the room, I’m representing the whole nation behind me. India is very misrepresented a lot… so I have to be very cautious about how I say, how I act. The title that you’ve just won… means a lot to the country. It’s not just about you.”

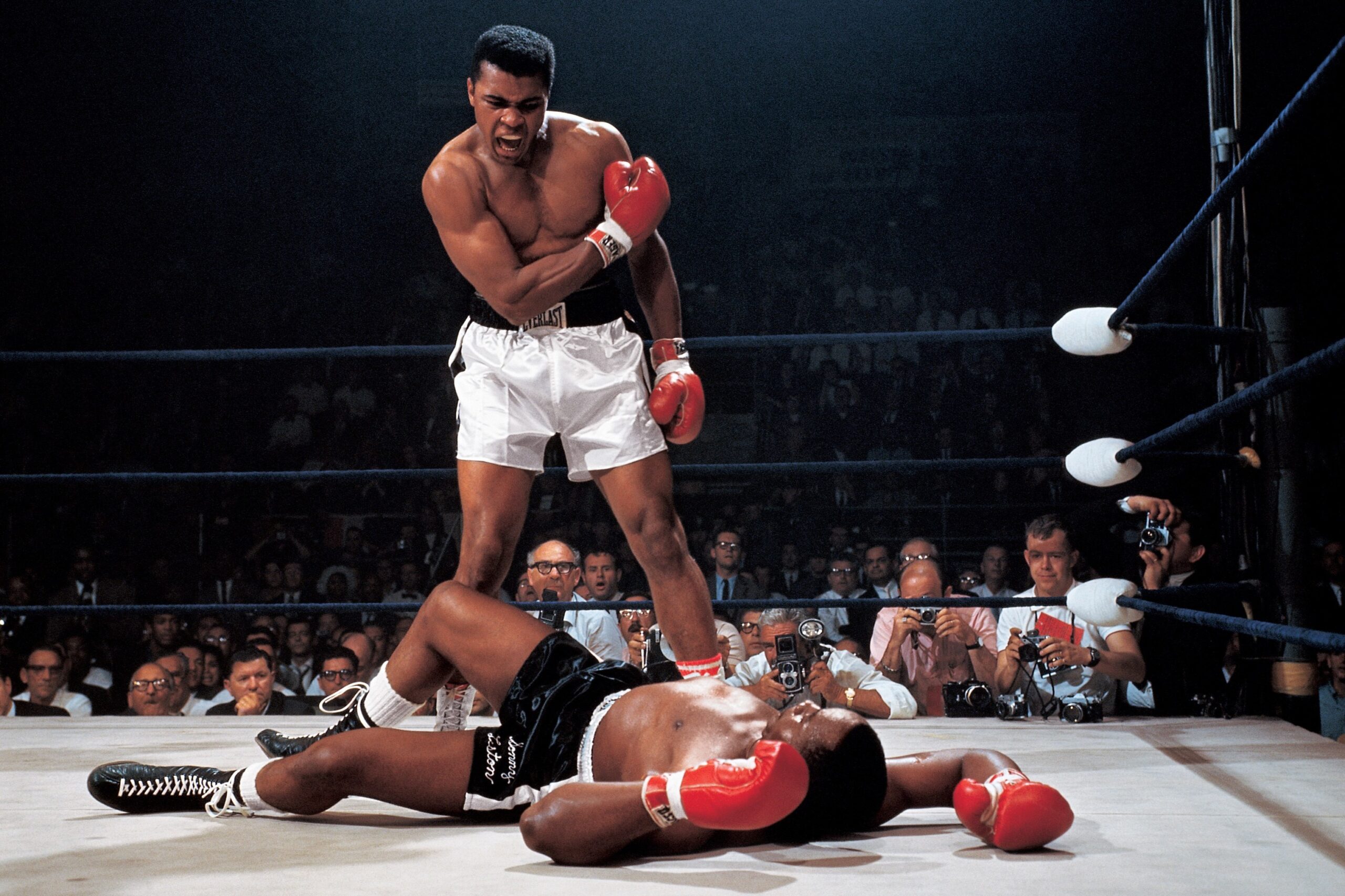

Anwar’s emblematic experience is not uniquely his, but rather a wider zeitgeist where achievement is met with scrutiny. The challenges faced by Anwar and Prince Naz reflect a long history of marginalised athletes beyond the ring. Muhammad Ali comes to mind. I grew up watching my father admire him as a man who confronted societal expectations of personal and cultural identity.

Muhammad Ali brought focus to the intersection of sports and social justice. Born as Cassius Clay, Ali changed his name in 1964, after converting to Islam and rejecting the ties of his birth name to slavery. One would think that this change would be met with tolerance; instead, he was greeted by the American media and taunts. Opponents would aggravate Ali, such as Earnie Terral, who famously refused to call Ali by his muslim name, stating, “His momma named him Clay, I’m gonna call him Clay.”

In 1967, Ali would fight Terrall and dominate him while taunting back the question: “What’s my name?” The question rang around the world, with many framing this new identity as his ‘dark side.’ Narratives were only fuelled further when he refused his military induction that same year.

Bravely, directed by his moral compass, he went against his government and faced harsh consequences by being stripped of his heavyweight champion title and suspended from the sport for three years. Still, he stood solid in his anti-war stance during his trial, which was initially cited as Clay vs. United States and later changed to Clay, aka Ali v. United States, where he outlined the difference between fighting as a boxer versus a soldier. Violence was for the ring, between two trained individuals who were willing participants, and he saw the Vietnam War as a senseless justification of cruelty that conflicted with his religious beliefs.

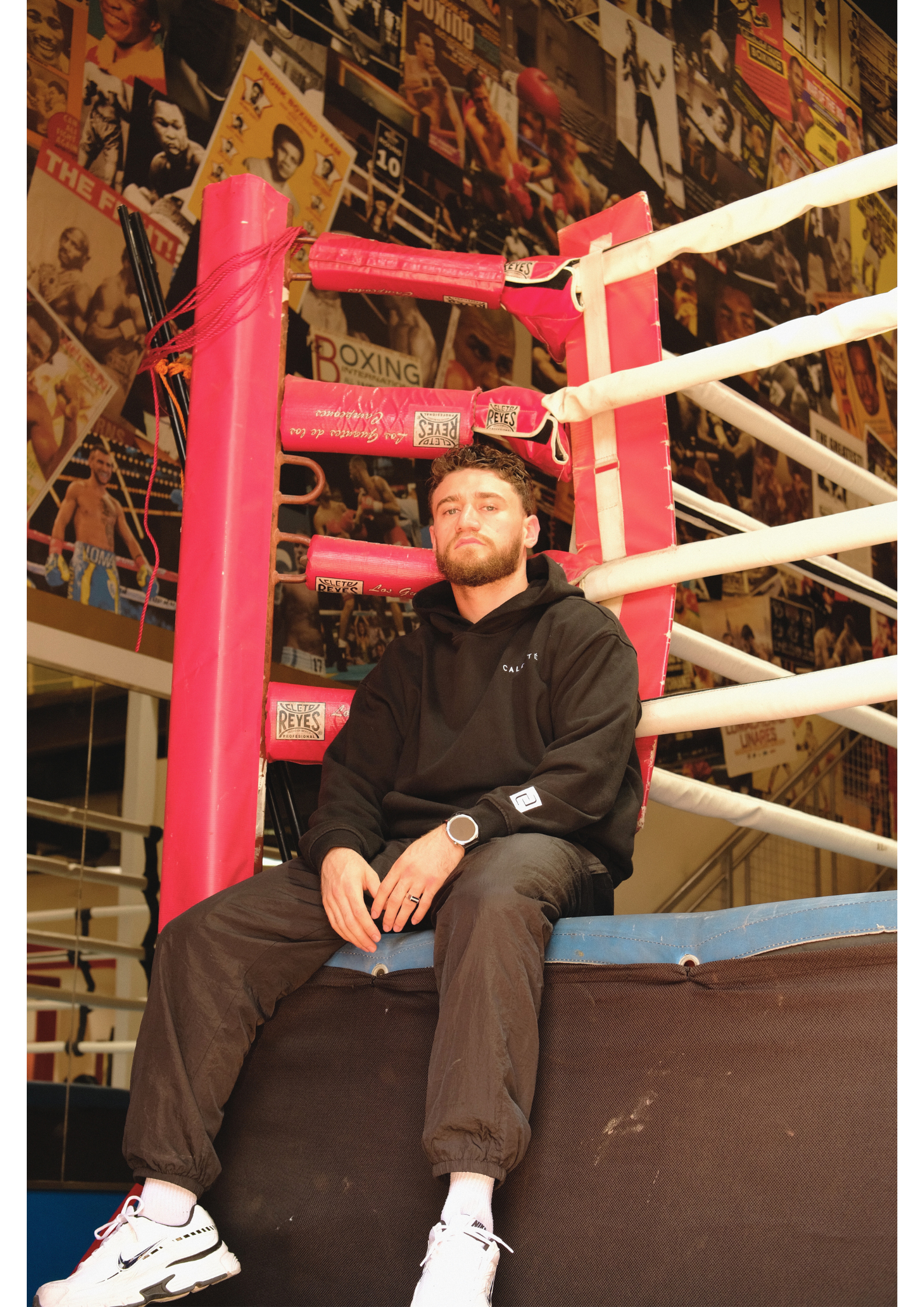

A complementary ethos was echoed by Yanal Bitar, who is set to make his professional debut at the end of the year. However, Bitar never took up boxing with a professional goal in mind. “When I was 16, I was going through a lot emotionally and I had a lot of anger issues,” he says. “I would break a lot of things around me, I’d make a mess, and I’d… questionable actions. And I found that boxing was a good way to release rather than be angry or break things. Like punching a bag just gave me the same sort of satisfaction without the mess.”

As a Palestinian, his pillars stand clear and strong; nationality, family, heritage. These permanent fixtures in his life are what sees as worthy of defending. He distances himself from the perception of aggressive impulse and positions boxing as a reclamation of self-agency, telling ICON MENA that his commitment to boxing is centered on accountability. A promise to himself above all else and rooted in control rather than chaos. He considers giving up as an injustice to not only his trainers but himself. “My foreseeable future is dictated by what I do today, not the excuses I make,” he explains, accountability as an internal strength he views as similar to the physical strength needed for boxing. In a polarising political landscape, the philosophies of Ali and Bitar align here: violence without purpose has no meaning. This is a quiet rebellion against the chronicles told in Western propaganda and news outlets.

In 2018, Saudi Arabia partnered with WWE in what was reportedly a billion-dollar deal, an addition to the region’s extensive investment in combat sports entertainment. In another attempt to bring the world to the Middle East, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have decided to re-enter boxing by bringing the biggest fights to the region, but the most noticeable thing about these cards is the lack of regional fighters.

I don’t need to explain this to Bader, “The Master” Al-Dherat. As a Jordanian fighter with a 12-0 record, he is acutely aware of the disadvantages Arab boxers face. The systematic inequalities of boxing present an additional barrier that Arab fighters must overcome. He locates a distinction between himself and Western opponents: “They still grew up in a country where there are a lot of opportunities.” Al-Dherat points to a contradiction that is impossible to ignore, despite the region transforming itself into a global playground for combat sports, local fighters remain on the sidelines, fighting in the margins while their Western opponents shine in the spotlight.

As one of the oldest sports in the world, dating back to ancient Arab civilisation, boxing has carved out a distinct identity for Arabs. The lightweight champion views combat as an ancestral “biological” trait in Arab DNA, as he even descends from the Bani Saker tribe. He says this not in a message of intimidation, but as a frustrating fact considering the unequal starting lines between fighters.

In the United States and Europe, boxers have ample opportunities to represent themselves in amateur fights and enter the professional ring with experience, which attracts investment from sponsors. For Arab and South Asian boxers, matches are few and far between, meaning external investment into their careers is sparse, and those that are good must be exceedingly great. This is not to say that Western fighters lack hunger; the difference is not in heart but rather route. A subconscious devaluing of Middle Eastern culture, rooted in Eurocentrism or centuries of viewing boxing through a ‘Westward gaze’, unsustainable representation limits opportunity. Such a challenge must be navigated through patience and belief in the outcome. For these boxers, belief is synonymous with faith, a pillar of strength they lean on.

Rowan Athale, British-Indian director of Giant, explained the significance of growing up in an era he calls “Nazmania.” Although he was Arab and not Indian, Prince Naz was a representative of the collective marginalized community of brown men in Europe. Similar celebrations are seen today, such as UFC champion Khabib Nurmagomedov, who became notorious amongst Arab youth in 2019. While the fighter was not Arab himself, he was Muslim, and this was a sufficient reason to celebrate his victories as a collective. For Anwar and Al-Dherat, their faith is a natural element of their lives, akin to breathing. Motivation is fuelled by prayer, and here, responsibility reasserts itself as purpose. Faith is an anchor that keeps them humble in the tides of pressure.

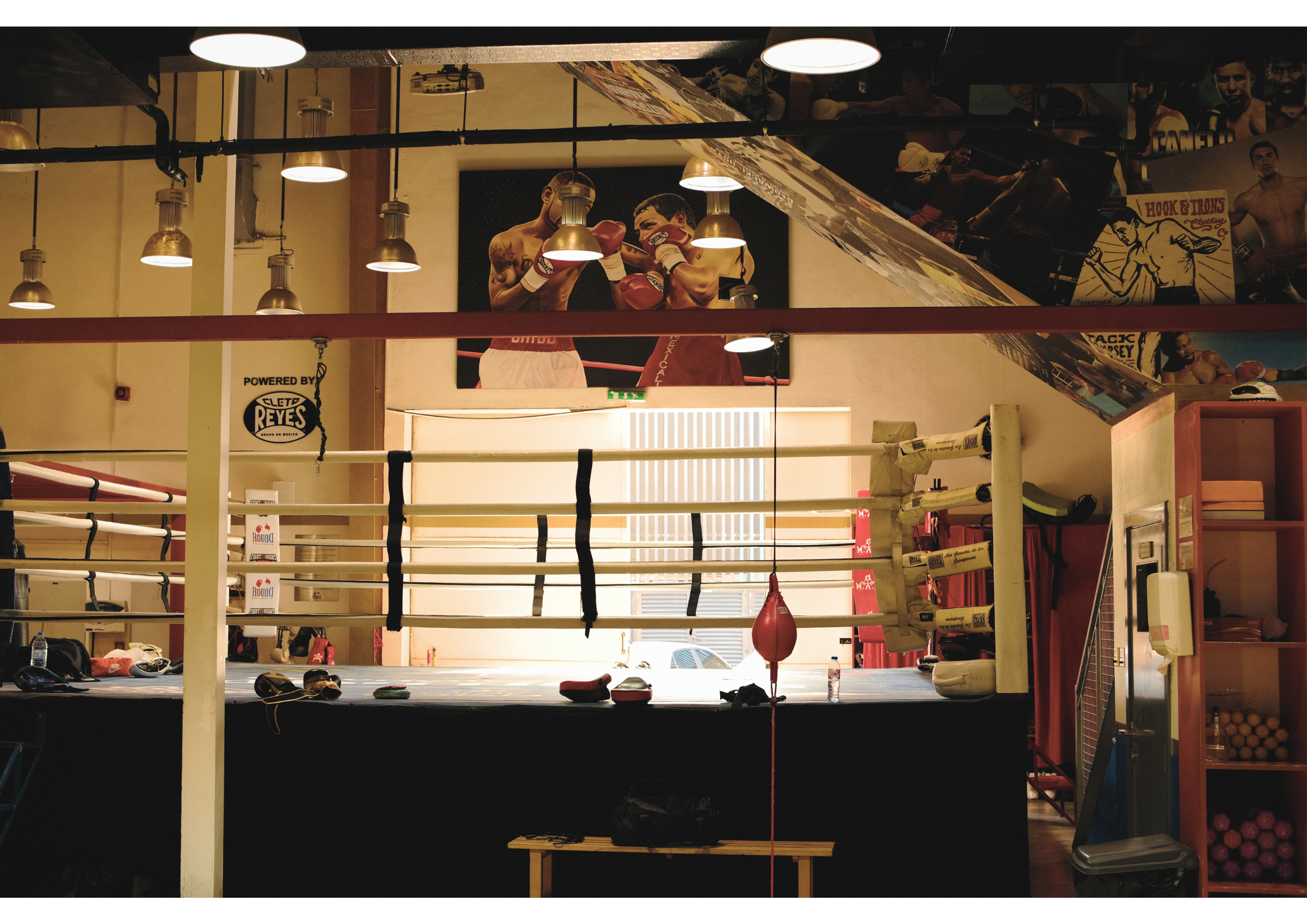

Boxing requires a routine and responsibility that the boxers structure themselves into. Around six to ten weeks before a fight, athletes enter a “camp” that is scheduled by days of intense training, opponent studying, and social hibernation. This is the reality of boxing that many are blind towards and my inner monologue kept asking, ‘Why would you do this? Is it really worth it?’

Instead of making assumptions myself, I directed the question to the three boxers. The answers have far less to do with Freud’s Thanatos, which argues that humans have a subconscious desire to express violence, than imagined. Against a backdrop where brown men are portrayed as disposable and threatening, the three fighters approach boxing with a deeply cultural discipline.

Al-Dherat explains with certainty that boxing sharpened his sense of responsibility as a professional fighter beyond the ring: “We carry weapons with our hands,” he says. “We have to be more responsible than normal people.” The feeling of responsibility extends into many areas of his life, shaping his understanding of masculinity and protection. “It’s really a shame if you’re a man and you can’t protect yourself,” he reflects, “How are you going to protect your wife or your kids?” As a husband, his capabilities are not grown from dominance, but rather duty.

While Al-Dherat’s connection to boxing is based on responsibility, Anwar’s is sparked by passion, a relationship he describes as inevitable: “Everything is a risk. But if you have a passion and love for it, you cannot control it.” What separates him from the casual boxer is not his dismissal of danger, but the acceptance of its position. Having boxed for 17 years, the sport gives him an unparalleled sense of purpose. If he had to stop, he would question himself, “Why am I here?”

Yanal Bitar’s initial attraction to boxing was different, acting as a reminder of perseverance. He recalls observing Sugar Ray Robinson fight; how he was moving through the ring as a dance. “People die more from boxing than any other combat sport, and he was smiling, having a great time,” Bitar explains, “I saw myself in that because I have this thing where when I face adversity, I smile.” An instinct to meet hardship with kindness may seem like a small gesture to reflect on, but it signals a dedication that can’t be bought. Bodily strength is obviously important in a profession where getting hurt is a part of the job, but the mental tenacity of these three boxers is what filters out hobbyists from professional boxers.

Prince Naseem and Muhammad Ali didn’t ask for their actions out of the ring to be scrutinised, as actions in the ring are examined. Naz was introduced to Brendan Ingle at age seven, after his father became worried that his small stature would make him an easy target for school yard bullies, and Mohammed Ali sought out boxing at age twelve, after his bicycle was stolen. Being good representatives of marginalized communities was not an expectation that their fellow boxers needed to achieve beyond victories, belts, and titles. They both started boxing as acts of self-defense, which later translated into passionate and motivational careers. While similar pressures are definitely fought today, a change is starting. Al-Dherat notes this evolution as a positive for the region.

“Not long ago, people always used to look up and say the west to the west, the west, the west, the west. Now the west is saying the Arabs, the Arabs, the Arabs, the Arabs.”

He also acknowledges his impact as a role model, receiving daily messages on Instagram from young fans seeking guidance, asking for his opinion, his advice, and how they might follow a path similar to his.

“We always used to look up to the people from the West,” Al-Dherat admits. “But things are changing their course, because now if a young boy wants getting into boxing, he wouldn’t look up to a man in America. He’d say: Wait, there’s someone in my own country, someone who came from my own set of circumstances, and had the chance to do it and got up and did it? So why would I not have the opportunity? Little Arab kids nowadays can say that. In my time, I couldn’t. It was always this imagination. But now the little kids they know that it could happen. They have evidence for it.”

More than this, a transition for boxing as an industry has sparked. Over the past decade, influencers and internet personalities have emerged in the boxing space, and at first, these promotional cards depended on fan viewership. Anwar observed little training and talent, feeling that the theatrics of bringing online rivalries to life were disrespectful to the sport he calls an “art.” However, as investment into the sport has become disciplined and not only monetary, he sees an improvement in calibre and effort put into the sport, going as far as to acknowledge many of these influencers as being “great boxers”. More than this, a new community and generation of boxing viewers have entered the arenas of the profession. Many who may have only tuned into boxing to support their favorite YouTubers, or watch Logan Paul get punched by Mike Tyson, are now avid fans of the sport.

While the region funds matches for Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury, they must not live to regret neglect of aspiration, determination, and talent existing within the region. While we, as viewers, must not be blind to the determination for self-advocacy, carried by a weight of representation for those who came before and those who come after. The fight starts long before the bell rings, and those fighters will make sure you know their name.