News

Everyone wants to be loved; or at least, most of us do. In the world of professional wrestling, boos and jeers are actually good for business. Compelling stories sell tickets, and as is the case in any good story, there need to be heroes for the crowd to cheer for and villains for them to root against.

One way that in-ring villains have reliably riled up audiences throughout the long and storied history of wrestling is by portraying a foreign menace, exploiting people’s fear and hatred of the “other”. In the United States, where modern wrestling has its roots, foreign menaces have taken on many forms, from Russians to sumo wrestlers to Nazis. Unsurprisingly, there have also been quite a few Middle Eastern menaces.

But the way that Middle Eastern characters have been portrayed in the west has changed a lot over the years, as have the types of characters that actual Middle Eastern wrestlers have been allowed to play, and this evolution can tell us a lot about how even in wrestling, where the lines between reality and fiction are blurred, real-world values, anxieties, and political tensions can be reflected, exploited, and challenged.

Wrestling is not “fake”; however, the results are predetermined. Much like theatre, performers take on roles and cooperate with one another to put on a show and create an illusion of conflict convincing enough to captivate an audience. These performers are part athlete, part actor, and the most successful of them are those who are just as skilled on the mic as they are in the ring.

Before wrestling’s true nature was as widely known as it is today, wrestlers and wrestling promoters had to speak in a sort of coded language so as not to clue audiences in on the truth of the illusion. All you’ll need to know for now is that a persona is a “gimmick”, a hero is a “babyface”, a villain is a “heel”, and when a heel gets a crowd to boo, that’s “heat”.

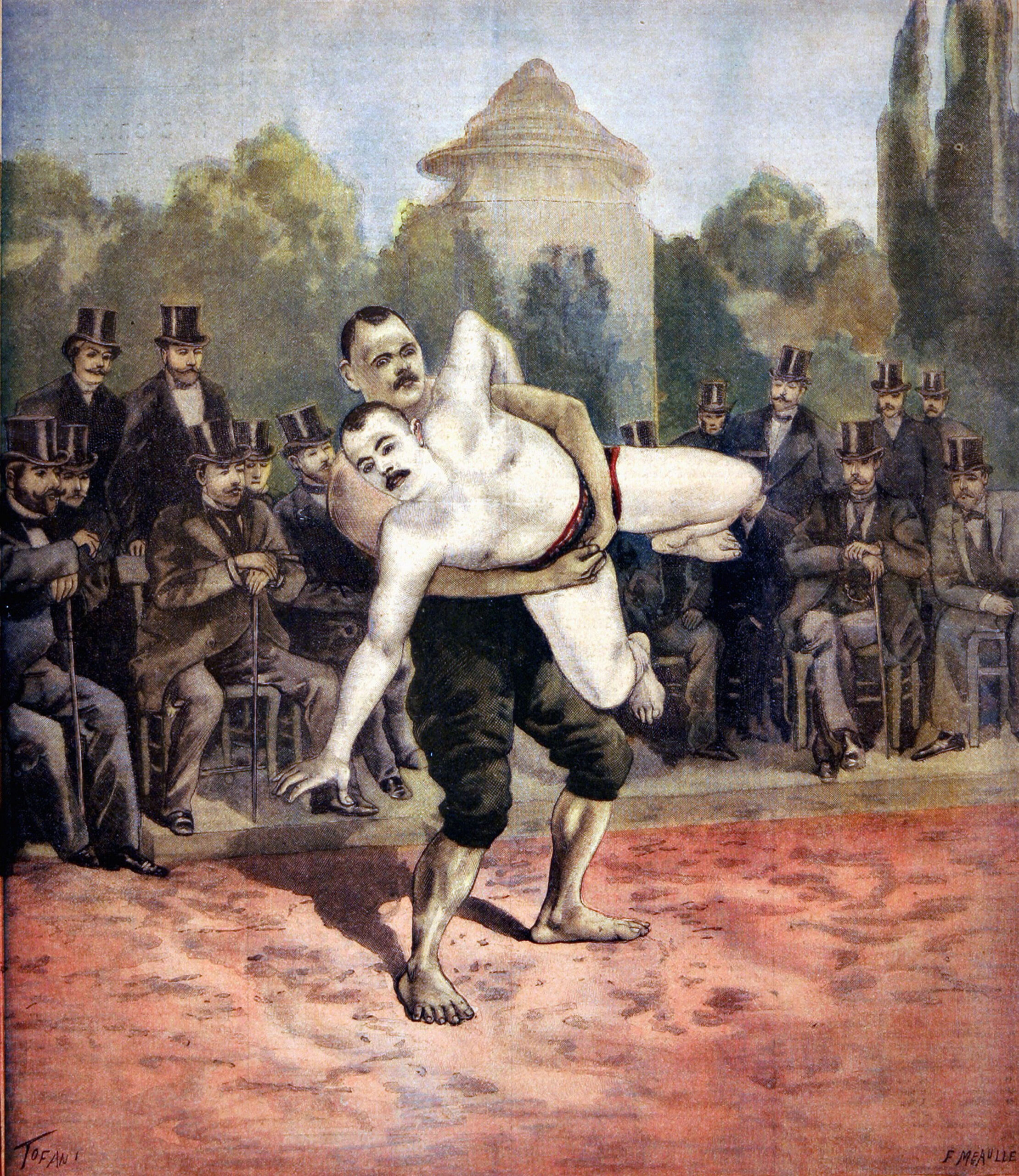

It could be argued that the very first Middle Eastern heel was Yusuf İsmail, a 6’2 305-pound Turkish wrestler who was brought over to compete in the United States in the 1890s. İsmail was billed as The Terrible Turk, the sultan’s favourite wrestler, a savage from abroad here to challenge anyone brave enough to face him. By the turn of the 20th century, other Middle Eastern strongmen would come into the picture. One of the most prominent of these wrestlers was Armenian Arteen Ekizian, who wrestled under the name Ali Baba.

Soon enough, a new variant of the Middle Eastern heel gimmick would emerge, one that would play up the exoticism of the region and see wrestlers dressing in fezzes, turbans, and keffiyehs to portray noble but mysterious sheiks. This trend likely stemmed from the popularity of the 1921 silent film The Sheik, which starred Hollywood heartthrob Rudolph Valentino as the wealthy and charming leader of a desert tribe. In the 1930s, Julian Arturo Herrera Haddad from Lebanon donned a fez and wrestled as Sheik Mar-Allah, and in the 1940s, Pedro Kuri, also from Lebanon, sported a keffiyeh and wrestled as Emir Badui.

With the advent of television, wrestling’s popularity exploded in the 1950s and colourful characters were in high demand. One such character would be The Sheik, a Middle Eastern heel who would inspire genuine terror in audiences and gradually shift from performing traditional holds and grapples to all-out brawling. As the Arabian madman from Syria, Lebanese-American Edward Farhat pioneered a more hardcore style of wrestling and became notorious for bloody matches that saw him biting, clawing, gouging his opponents in the forehead with a pencil, and even throwing fireballs.

Although it would evolve throughout his decades-long career, The Sheik’s elaborate entrance into the ring brilliantly demonstrates how he strategically played into orientalist Middle Eastern tropes and stereotypes to get heat and reinforce his villainous persona.

Dressed in a robe, keffiyeh, and curled-toe boots, The Sheik would enter the ring, lay down a small rug, kneel on it, and glare at the crowd, expecting silence, before lifting his arms into the air and bowing in prayer. Sometimes he’d be accompanied by a member of his harem, a woman whose face is completely obscured except for her eyes, and bark orders at her in some unintelligible language, demanding that she remove his attire for him and even kiss his feet, all while pushing her around and threatening to hit her.

But in reality, Farhat wasn’t Muslim, he was Maronite Christian. What he would yell was complete gibberish, because he didn’t speak Arabic. And the harem girl was actually his wife Joyce, who gladly agreed to play the role.

What made everything about The Sheik that much more believable was that up until the day that he died in 2003, he never publicly broke character. His popularity established a new template for the Middle Eastern heel, and similarly despicable Middle Eastern characters like Skandor Akbar (Jimmy Saied Wehba) and The Great Mephisto (James Ault) would become common in the 1960s and 1970s.

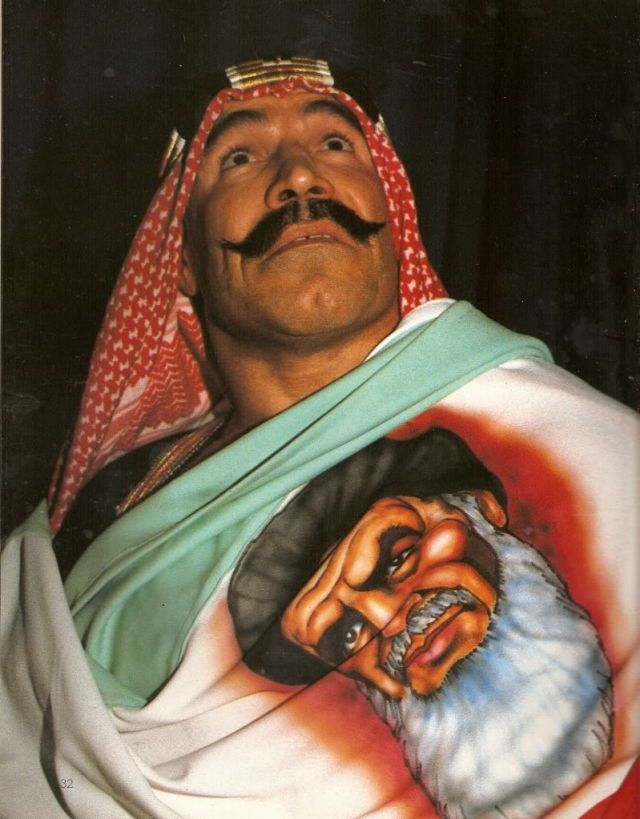

As time went on, Middle Eastern heels would begin leveraging real-world geopolitical tensions for heat. In the 1980s, in the wake of the Iranian Revolution and the Iran hostage crisis, Iranian wrestler Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri rose to prominence in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) as The Iron Sheik, a Middle Eastern heel who was unabashedly anti-American, singing the praises of Iran and berating the United States. Even the campy all-female promotion Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling (GLOW) had their own Middle Eastern heel in Palestina, played by Janeen Jewitt, a Syrian terrorist who would come out to the ring, wielding a machete and even kneel on a rug, just like The Sheik.

Current events would once again become a source of inspiration in the early 1990s when all-American babyface Sgt. Slaughter became an Iraqi-sympathiser during the Gulf War and pledged his allegiance to Saddam Hussein, to the outrage of many. Sgt. Slaughter aligned himself with Col. Mustafa, an alter-ego of The Iron Sheik, and General Adnan, a character played by Adnan Al-Kaissie, an Iraqi wrestler who had actually gone to school with Saddam Hussein in his youth. It’s said that this heel turn led Sgt. Slaughter to receive legitimate death threats.

The decade would also see the rise of Sabu, a top star of Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW), who also happened to adopt a Middle Eastern gimmick. For Lebanese-American Terry Brunk, this gimmick wasn’t just a creative choice, it was a matter of family legacy. Trained by his uncle, The Sheik, Brunk would go on to popularise a more high-risk style of wrestling that would see him backflipping out of the ring and crashing through tables.

WWF were interested in signing Brunk to portray The Sultan, a masked and mute Middle Eastern heel whose tongue had been cut off, but Brunk rejected the offer out of loyalty to his uncle when he learned that he would be managed by The Iron Sheik. The Sultan would ultimately be portrayed by Samoan wrestler and future-Rikishi Solofa Fatu.

World Wrestling Entertainment (WWF, after a 2002 name change) would attempt a Middle Eastern heel character once again in the 2000s, though this would ultimately turn out to be the last one of note.

In 2004, Italian-American wrestler Marc Copani was pitched the idea of portraying Muhammad Hassan, an Arab-American dissatisfied with how he and Arab-Americans like him have been treated following the 9/11 attacks. Paired with Iranian-American wrestler Shawn Daivari, who would play his manager Khosrow Daivari, Hassan made his WWE debut in late 2004.

In his first on-air appearance, Hassan decried the prejudice that he and his people have had to endure and spoke out against the war in Iraq. Copani would later reflect on the gimmick and state that he got genuine heat because everything he was saying was true, and it made Americans uncomfortable. Unfortunately, what had the potential to become a more nuanced take on the Middle Eastern heel character would be reduced to yet another villainous Arab caricature, and although WWE were no stranger to courting controversy, a tragic real-life incident would force them to pump the brakes on the Muhammad Hassan character altogether.

In a 2005 episode of WWE’s weekly program SmackDown!, Hassan’s manager Daivari would face The Undertaker, a wrestler who portrays an undead undertaker. Hassan accompanied Daivari to the ring, and after he was pinned by The Undertaker, knelt down and “prayed”, summoning a group of ski mask-wearing men to beat up and choke The Undertaker, before carrying the unconscious Daivari out of the ring.

The episode was taped on July 4, but wouldn’t be broadcast until July 7, which happened to coincide with an actual terrorist attack, the July 7 London bombings. The segment aired unedited in the US, but was removed from European and Australian broadcasts of the episode. After UPN, the network SmackDown! appeared on, pressured WWE to keep Muhammad Hassan off their network, the character was written off of SmackDown!, and Copani was let go from the company.

Unfortunate coincidences aside, wrestling had become more international, the world had become much less tolerant of these types of characters, and as the years went on, broader societal conversations around diversity, inclusion, and representation would also begin to influence wrestling.

In the 2010s, numerous wrestlers with Middle Eastern backgrounds would join WWE and take on gimmicks that had nothing to do with their ethnicities. Aron Steven Haddad, of Lebanese descent, debuted in 2012 as Damien Sandow, a condescending intellectual heel. In 2013, Dean Muhtadi, whose father is Palestinian and mother is Syrian-American, debuted as Mojo Rawley, a high-energy babyface who encourages people to “stay hype!”.

The most popular and groundbreaking of this new generation of Middle Eastern wrestlers would have to be Syrian-Canadian Rami Sebei, better known as Sami Zayn, who would debut in 2013 as an optimistic underdog babyface and go on to become one of the most popular wrestlers in the entire company. Although his gimmick has nothing to do with the fact that he’s Arab, Zayn never shies away from highlighting that aspect of his identity, wearing wrestling attire that features the word “Zayn” written in Arabic, addressing an audience in Arabic while in Saudi Arabia, which WWE signed a strategic partnership with in 2018, and even wearing a keffiyeh in support of Palestine.

Though it may seem like the Middle Eastern babyface is a more recent phenomenon, there have actually been quite a few in the past. In the 1940s, a Canadian wrestler whose name has been lost to time portrayed Sheik Lawrence of Arabia, a sheik-themed babyface. In the 1950s, Lebanese expat Wadi Ayoub began wrestling as Sheik Wadi Ayoub in Australia, where diverse migrant communities rooted for wrestlers who represented them in the ring.

And it should go without saying, but one place where the Middle Eastern heel gimmick was certainly never a thing is the Middle East itself, where various countries in the region have their own local wrestling histories and heroes. Lebanon’s Jean and Andre Saade were considered popular athletes in the 1960s and even starred in a handful of films. Mamdouh Farag brought wrestling to Egypt in the 1990s and is credited with popularising it in the Arab world through several television programs he hosted in the 2000s.

Wrestling will always need heels, heels will always need babyfaces, and the stories told through them will always be what draws fans of all cultures and backgrounds to wrestling. But at the end of the day, the desire to overcome adversity and emerge victorious is universal, and everyone deserves a chance to see themselves as the babyface.