News

Raised in a home built atop the remnants of an ancient Sumerian burial site, Zayn Qahtani has always been acquainted with death. “I’m a graveyard girl,” she professes as we sit in her London studio, explaining that the singularity of her homestead meant constantly learning about ancient burial rituals, about how the Sumerians would have dinner with their deceased one last time, together with their close family and friends. “It just made death seem like so much of a scary thing, like it’s part of your routine… Maybe that’s why my life has a lot to do with death, grief, rebirth, because I relate to that wanting to make death casual.”

Qahtani’s artwork has come to gloat of this proximity; always tangled up in grief, but never burdened by it. Only marked by a knowing detachment. She handles her art—intricate drawings enshrined in sculptural framings—with the same distance, despite how intimately autobiographical they all are. Qahtani is gripped by the process of creation alone, of excavating the secrets of her subconscious through her work; once her pieces are complete, she is easy to part with them. For someone so naturally warm, the artist has an openly dark, almost morbid streak to her words, which suggests a life thoroughly lived. “I have no attachment to anything,” she admits. “The catharsis, the release, happens when I’m making it. I don’t have to think twice. The process was done for me, so you get to keep the final piece.”

Though raised in Bahrain, Qahtani moved to Woodchurch, England, in 2020, and then to London in 2022 for a string of intensives and exhibitions. Currently doing her second residency hosted by Josephine Bailey, she has settled into an upper recess of a repurposed farmhouse—formerly a fabled recording studio of Kylie Minogue—sustained alone by mushroom matcha and a compulsion to exalt her inner world through the melding of drawing and sculpture. Venerative in their totemic forms, her works are always eternalising a moment or a spiritual lesson of some kind. They are strewn across her hardwood floors when I arrive, jolted by the sight of such delicate pieces scattered like confetti ready to be swept up (perhaps an early tell of her detachment).

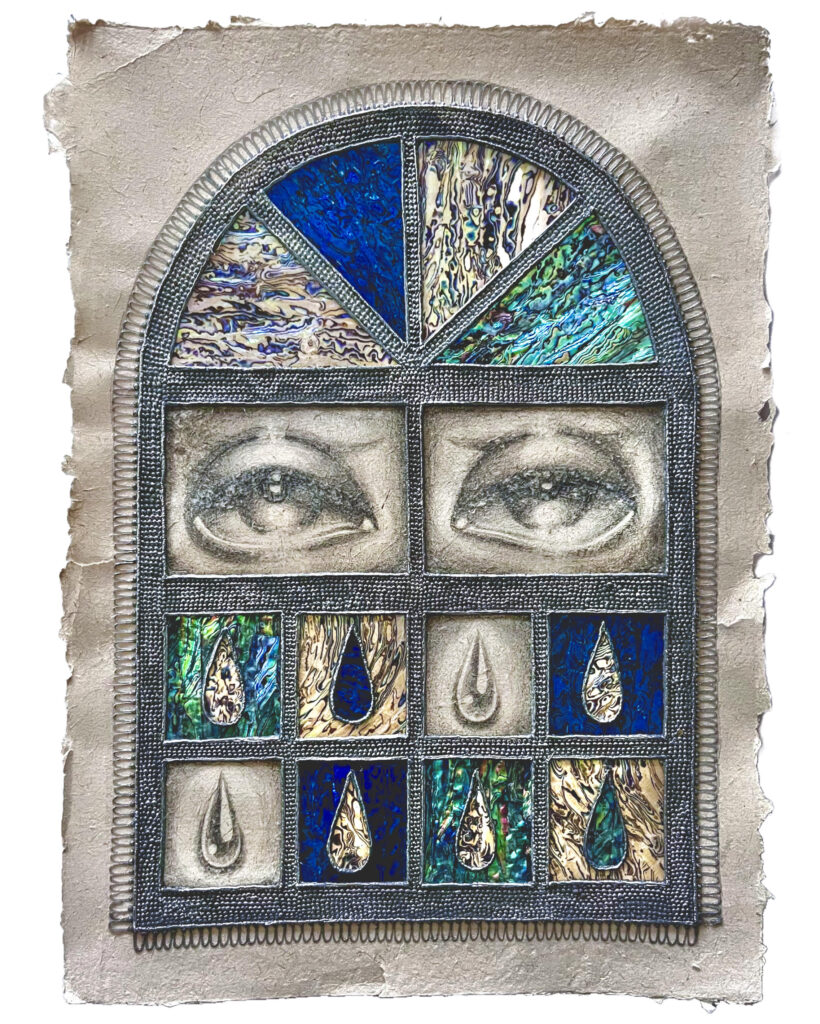

Hunched over an arrangement titled The Alchemy of Sadness, Qahtani translates the meanings behind each element, which together were inspired by the archetype of The Magician from the traditional Rider-Waite Smith tarot deck. Four separate pieces—an eye, a teardrop, an eight-point star, and a pearl—rest underneath a magician, representing her tools. “I use these symbols quite often to represent sadness being transformed into beauty or release, or an emotional acceptance or understanding of things.” The installation is a deliberate progression: the eye formed a teardrop, and the teardrop hardened into a pearl. Qahtani explains that pearls only emerge from shells that have caught disturbances, like dead animals or grains of sand, with the pearl manifesting as a make-shift band-aid over the original grain. “I really like the idea that something so precious and sought after and rare and beautiful can come from a creature’s pain. So these are sort of my magician’s tools.”

Of her tools, Qahtani spoke endlessly. Graphite, gilt polylactide, Bahrani date palm paper, mother of pearl… but it is the abalone shell that suffuses each piece with a shimmering air of sanctity. This shell can be found in all of her work, creeping up the frames of it, guarding her drawings with stark barriers of liminality. She often dyes the material black to a humble effulgence, allowing blues and purples to gleam through it. “Abalone shell fascinates me, I’m a bit obsessed with it. You know how Golem really likes his ring? It drives me to madness. I feel like that’s eventually going to be me,” she muses, greeting my grimace with a placating smile. “In a good way; I kind of feel like it’s the only way.”

Having grown up by the sea, Qahtani is an old friend to the shell. One of her favourite things to do as a child was to hunt along the beach for any small, discarded treasures, basket in hand. “Sometimes I’d find really crazy things like tiny statues from Hare Krishna celebrations. Once I found this beautiful moonstone ring, but a lot of the time you’ll just see piles and piles of these open shells all the way out just catching the light in the most beautiful way,” she shares. “It’s because fishermen would eat the oyster and then discard the shell… One man’s trash, you know?”

For all the time she had marvelled at these earthly delights, Qahtani had only begun to sculpt with them during the pandemic, when she borrowed her nephew’s birthday present, a children’s 3D printing pen, and began experimenting. She did her research first—earning a Master in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art just last September—and her deep knowledge of the materials brims to the surface in an excited flurry as she speaks. I soon learned that polylactide, a bioplastic made from sugar cane and corn starch, exists in multitudes, and produces different finishes depending on the material it is infused with. That polylactide combined with metal powders, when sanded down, renders a thin veneer of metal that gives an aluminium or copper-like look to sculptures. Mixed with wooden or ceramic fibres, it yields wood-looking sculptures. “I started using the pen and making these really sh*t sculptures. I was so interested that you could put material in it,” she beams. “And you can make anything from it. The possibilities are endless. It’s so bizarre and amazing to me; it makes me feel so powerful.”

Soon, keeping drawing, painting, and sculpting separate felt like an unnecessary act of restraint for Qahtani. Affixing her sketches to sculpted frames encrusted with raw materials, she began to find her language. “I just felt this calling to use materials that are traditionally used in the Middle East, like shell inlays, and trying to look at the way traditional chests and woodwork was done,” she expounds. “It’s really prevalent in Bahrain. So it’s adopting these patterns, but I guess also innovating them, using bioplastic to recreate all those familiar things that I grew up around, because it sort of makes your language feel really honest.”

Working between England and Bahrain, she found herself more creatively articulate in her homeland. The materials she sourced from it kept her tethered to that ease when she was back in the smog of London. “If I look at my materials like a language, then when you’re constantly surrounded by that language you’re more fluent in it,” she explains. “It just makes sense. In London, I feel like I’m constantly grappling to keep my language going.”

Qahtani’s initial transition to London is what inspired her first solo show, Angels in Purgatory, in 2022. “The show was about my experiences of descending into the chaos of moving, and how it took a toll on my mental health—but that wouldn’t have gone into the press release,” she smirks. The press-approved concept was framed around the story of Nephilim, the Biblical offspring of fallen angels who, having disappointed God in some way, roamed the earth, spawning half-human hybrids. “It’s the idea of being half this untainted soul, and then all the moral grayness of being human. It’s really how I felt at the time.”

Nights blurred together for Qahtani in those early months. From nine in the evening to seven the next day, she would take refuge in her studio as though it were a lair, hardly ever seeing sunlight. The art that emerged through it was otherworldly: soft, psychedelic scenes in pastel watercolours, gilded with ornate, fanged frames. “The whole show was about existing in the dark space both literally and subconsciously,” she imparts. “It was also the first time I had used abalone shell in my work around the border of the frame, because I had wanted to make these spiked, almost architectural frames. They were grey and silver because they reminded me of the buildings and weather in London, and sort of the harsh grey reality. The outer surface.”

Past the spangled edges, celestial squirms of abalone shells fill the space before the illustrations. Each of the pieces are celebrations of the interstitial. “The abalone was supposed to be this sort of mid-section into the journey in the centre, where it’s sort of the in-between world,” Qahtani elucidates that even the shell itself is of the in-between, suspended between its hard exterior and the pearl, or even the oyster’s flesh at its core. “There’s this sort of iridescent, transient, changing quality. It’s got this Twilight-Zone vibe to it, where it’s not here nor there, it’s not like nor dark. When I look at it, it’s so strange that it comes from the earth. I love it.”

Angels in Purgatory was a prelude, in retrospect, to Qahtani’s very recent solo exhibition with Tube Culture Hall in Milan, Italy. Titled Divining the Darkness, the show was about the human iterations of ‘divination,’ the mortal mechanisms we use to fumble our way out of despair. “In my opinion, human divination is sleeping for really long hours, or having a big cry in the shower, or small things that give you big revelations,” the artist conveys. “It’s sort of like the natural version of being psychic. It’s like you don’t need closure because you’ve done this thing and you’re giving yourself closure. So the whole show is revolving around a psychological darkness and finding ways to get out of it.”

Pieces like Praying to Parts of God and Behind Closed Doors depict eyes welling with tears, piercing in depth. In another work, two figures hold each other’s cheeks in consolation, the sculptural frames consecrating the tenderness of the moment. No matter the scene in her illustrations, it’s Qahtani’s sculptural work that commands an instinct of reverence from its viewer. “I find the idea of veneration fascinating,” she discloses. “The idea of taking sadness, or any sort of emotions that are a bit jarring, and elevating them to this venerative viewpoint. Like being able to look at things that are a bit uncomfortable through the lens of accepting it as this all-natural thing.”

Perhaps it is her contentment with death that manifests the reverential aspect of her work. “When people look at death—which is inevitable, as a shock—it’s so counterintuitive, because it’s just as natural as a pregnant woman,” Qahtani observes. “When you look at a pregnant woman, you know she’s definitely going to give birth, but when you look at a human…like I often look at my friends and have the intrusive thought: ‘You’re going to die, we’re all actually going to die….’ And it comes into my head a lot, like daily. Maybe it comes from my fear of the unknown as well, that I want to make death so casual.”

All too cognizant of life’s fleeting impermanence, Qahtani creates little shrines, relics of each ephemeral moment, worshipping them to materiality with her magician’s tools: the ore of the earth itself. “It’s just naturally how I look at sadness or grief that is in my life. I’m constantly celebrating it, putting it up on this pedestal of wow, I got to experience this, that’s crazy.” Even as she contentedly lets them go, each piece of her art holds its place—be it in Soho House’s Art Collection or a buyer’s living room—compelling ekphrastic analyses with its startling rarity for all those who come to stare.

Qahtani’s forthcoming solo exhibition, happening next year, will be a transformative third act. “I’m feeling a lot more confident doing sculptures that aren’t just hand-in-hand with my drawings, like sculptures for purely sculptural purposes” she offers. “A lot of the work is going to be object-based, maybe stand-alone sculpture—who knows?”

WORDS: Maya Abuali