News

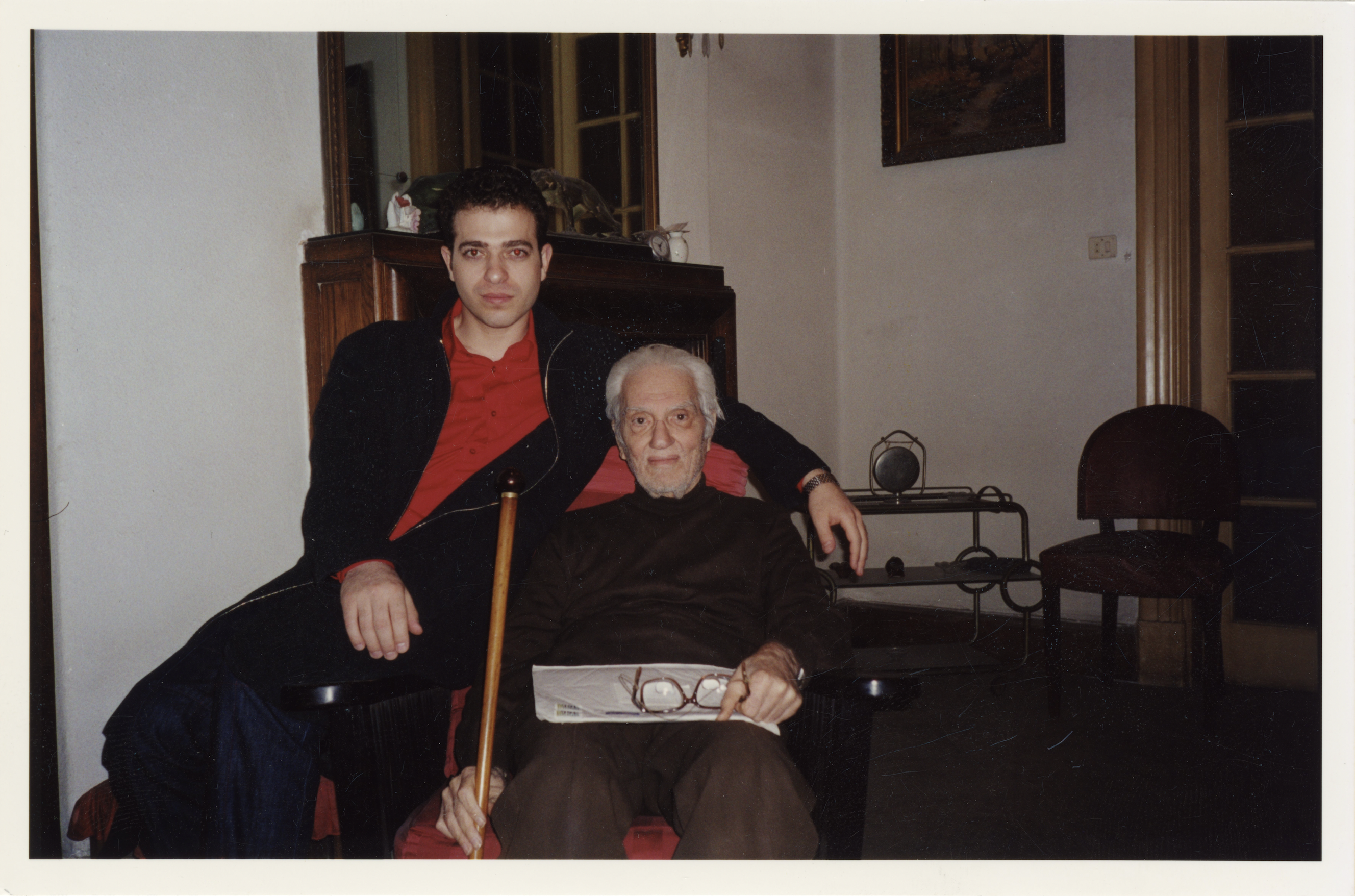

I first met Van Leo in 1991, when I was 19. I was starting to get into photography at the time and looking for a lab or someone to print my black-and-white photographs. As I was walking through Downtown Cairo, his studio caught my eye. The window display featured all those beautiful stars photographed in all their glamour. It stood out because most other studios in Downtown were doing only colour portraits of people and families. Coloured photography was the new thing back then. Van Leo, however, maintained his line of black and white glamour portraits.

I knocked on the door. It took a while for someone to answer. I knocked again. Van Leo opened the door and welcomed me in. Stepping inside, I instantly felt at home, as though I was visiting a grandfather or a family member.

The walls were adorned with portraits of Egyptian stars I adored, from Faten Hamama and Omar Sharif to Magda, Farid Al-Atrash, and even the esteemed writer, Taha Hussein. Their faces gazed down from the walls. “Who is that man?” I wondered silently, as he invited me to sit.

“How can I help you?” he asked, thinking that I wanted to be photographed or something.

“I’m actually looking for someone to print my work,” I replied.

“I don’t do that,” he said. “But let me see your work.”

I showed him my work, which he seemed to show true, genuine interest in. “Who is he? And who is she?” he asked about the people in my portraits, who were mainly friends and family. Of course, I was a little bit rebellious at that age and it showed in some of my portraits.

“I like your work,” he said. “Listen, I don’t print for anyone, but I would print for you.”

I was very touched and very grateful.

“You have to come back because I need to show you tests and you can tell me if you like it.”

And so I kept going back. We met again and again. Always in his studio, he’d show me whatever he was doing with the printing of my work, and I waited for him to print. Little by little, he invited me into the darkroom, to witness and see the whole process.

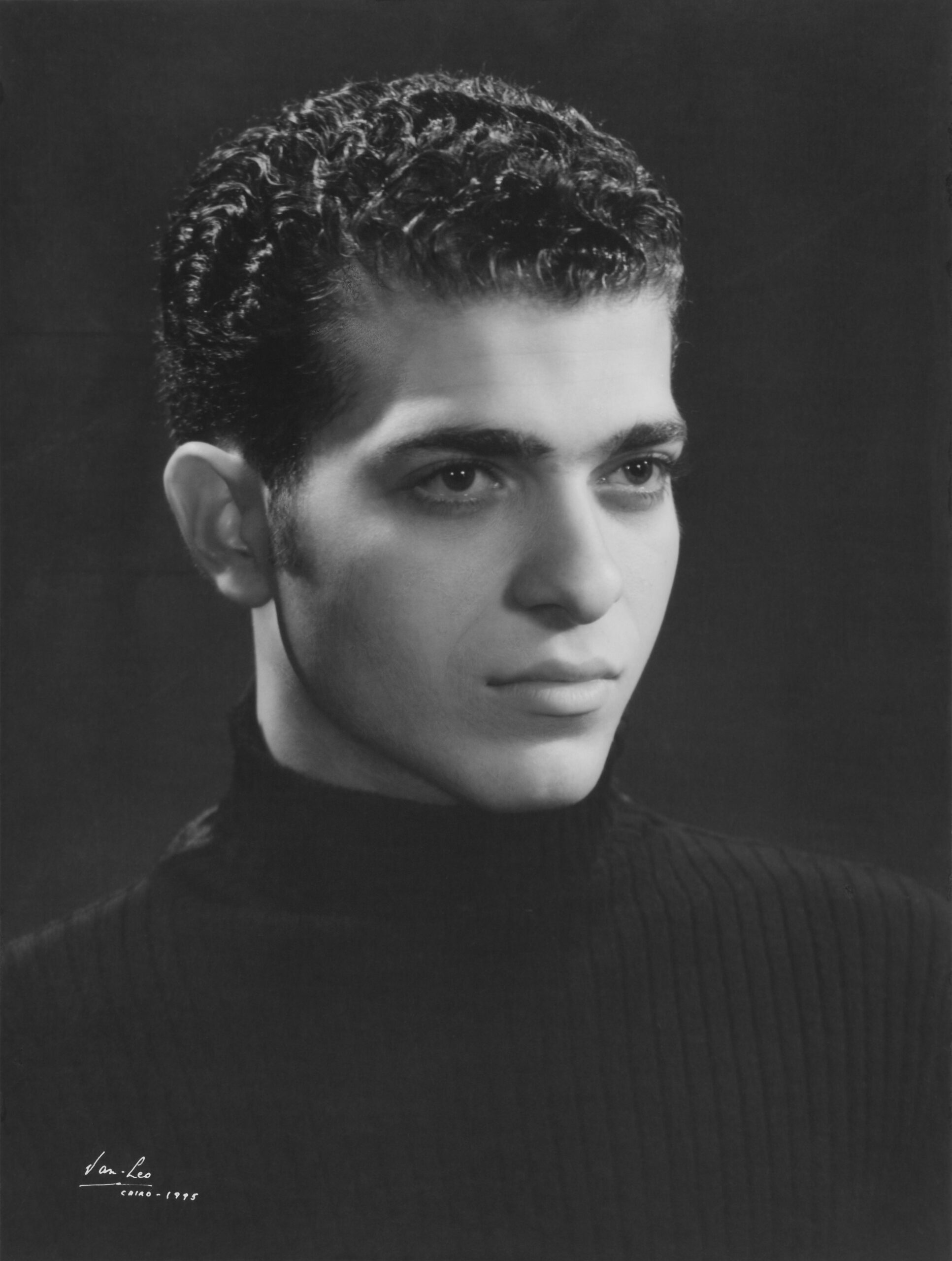

I must mention here that for two years in a row, I was rejected by every art and film school I tried to enter. So I decided to do my own art and started photographing my friends, family, and myself. Then came this chapter when Van Leo entered my life and started to print my work. It was the first time I got to see my work printed. I didn’t know that he was a photography master in Egypt. The encounter between us was very spontaneous, and it wasn’t about him being a known photographer, or about me being a young photographer. I just wanted to print my work, that’s all.

So we had this professional relationship where he would print my work every now and then, and it was a little business between us. Sometimes I even rented his studio for some of my photographs. If someone asked me, “Do you have a studio?” I’d say that I don’t have a studio (I was 19 at the time) but I can go and shoot at my friend’s, Van Leo. I always had this in my mind – I can call my friend Van Leo and go shoot in his studio.

Next to that, we were also great friends, and we used to meet a lot. I would call him all the time on the phone, we spoke together in Arabic, English and French, and he would call me too. This was before mobile phones, so we had a landline phone. I would go back home, and my family would tell me “Van Leo called you”, and then I would call him back, and we’d talk on the phone for a long time. He would ask me to go to his studio to show me his own latest works and hear my thoughts on them.

We started this exchange, artist to artist. I realised that there was something beautiful happening there. I didn’t do exhibitions or such to meet other artists, and then suddenly I had another artist in my life. He was my first artist friend, who was also printing my work. I could trust him. I could show him my work. He could trust me and show me his work. He was my best friend, or my only artist friend. I could talk to him about anything.

We would also have many personal conversations about his family, about him wanting to leave for the West, his brother Angelo, the inheritance and what to do if something happened to him. He started showing me work he never showed anyone while voicing his concerns and worries about what was happening to Egypt back then. Despite being 50 years apart, I never even thought of him as older than me. Sometimes I felt like he was as young as I was, but he was trapped in that old body.

I learned at a later stage that he had an issue trusting people. I think he trusted me. Maybe he thought, “Okay, he’s young. I can trust him. He’s very spontaneous. He just wants to print his work. He believes in photography like me. I understand that there’s no place to print or exhibit photography in Egypt. I understand that photography is not appreciated here yet”. Somehow, he saw a younger version of himself in me – a young photographer trying to make it in Egypt. He knew how difficult it was.

There were no photography exhibitions or anything of that sort. Photography in Egypt was exclusive to documentary photography, photojournalism, some historical war photography, and then you had studio portraits.

When I first started, I would try to contact a gallery to arrange an exhibition. Later on, I learned that it’s something you should never do, but I was very young and just wanted to show my work in my country. I was always met with the same response, “We don’t show or sell photography.” You had to be making paintings or sculptures to be considered an artist in Egypt.

Van Leo saw my passion and struggle, and let me enter his life. We were like two birds that belonged to the same environment. We met because we belonged to the same kind of art. We were the same type of artist.

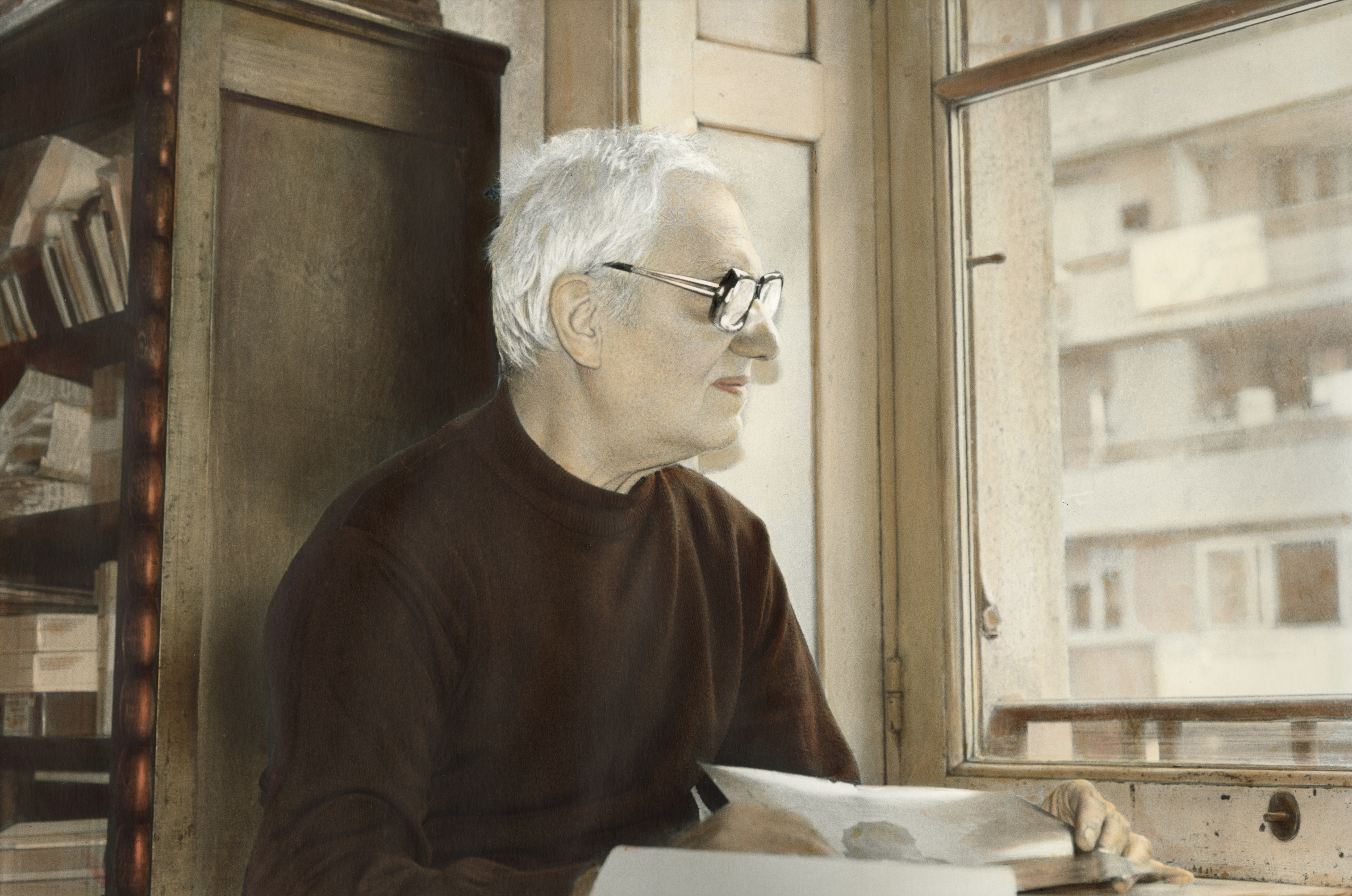

Van Leo had a very sad, almost pessimistic outlook on things, however. We used to sit next to the window in his studio, on the table where he used to sit and retouch the photographs in the daylight. I would bring him chocolate-covered dates from a shop called Groppi because they were his favourite. Then he would make tea, and we’d sit at the table drinking tea and talking about our lives and Egypt.

He would look outside the window and say, “Look how messy the streets are, and how people are becoming more conservative.” Van Leo noticed this change and it alarmed him to the extent that he burnt nude portraits he had taken of women because he feared they might land him in trouble at some point.

He would always talk about how Egypt was changing, and how it used to be more elegant, romantic and open-minded. So he lived a sheltered life in his studio, peering out of that window at the new Egypt that he didn’t agree with, reminiscing over the past, and regretting not leaving.

“You need to leave Egypt,” he would tell me. For him, I was like a younger brother that he needed to advise. “You’re making it more difficult for yourself by staying here.”

By 2003, I already had three exhibitions in Egypt and started getting known for my work in my country. I was meeting curators and artists, but I knew I needed to leave.

I was 30 when I first left Egypt. I travelled to Paris on an invitation from the Ministry of Culture for a ten-month artist residency, which eventually extended to three years. When I left I knew that I was not going back to live, I was only going back to visit. Suddenly my relationship with my work changed. I knew I was in Paris for a limited time, but then I also felt the same in Egypt all the time – that I would leave one day.

Whenever I visited a new place, I understood that my time there was limited, much like our time on Earth. We are here in life for a while, then we will all leave. I wanted my work to capture that personal sense of impermanence, a feeling that struck me deeply when I found myself in a new place among unfamiliar faces, in a new country, starting a new life. I didn’t know anyone. I didn’t have money. Everything felt so uncertain at that time for me.

My art is inspired by personal experiences that I lived. When I was living in Egypt and I was watching a lot of Egyptian movies on TV, I felt an urgent need to meet the actors I love before I die, or before they die. I needed to meet them and present them the way I saw them.

I wanted to talk about that. I wanted to talk about how we are all visitors here, and that I feel like a visitor everywhere I go. This feeling led me to start taking self-portraits back in 2003. Prior to that, I had dabbled in one or two experimental self-portraits that remained unseen for a decade. I would intensively take self-portraits when I was the only person around to photograph. I mostly do them from my back because it could be anyone. It’s all of us. My self-portraits are a visual diary of my life, they come to me, and they are taken in places I want to connect to my story.

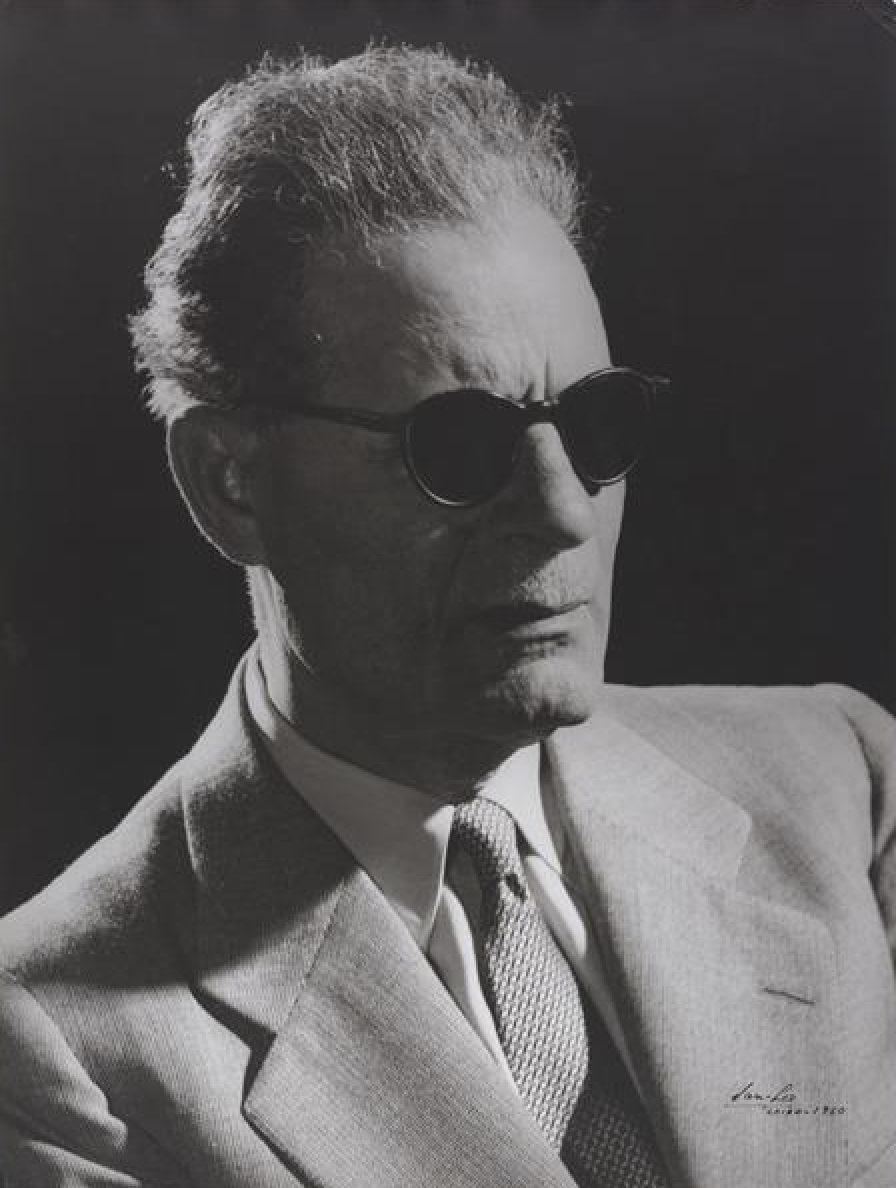

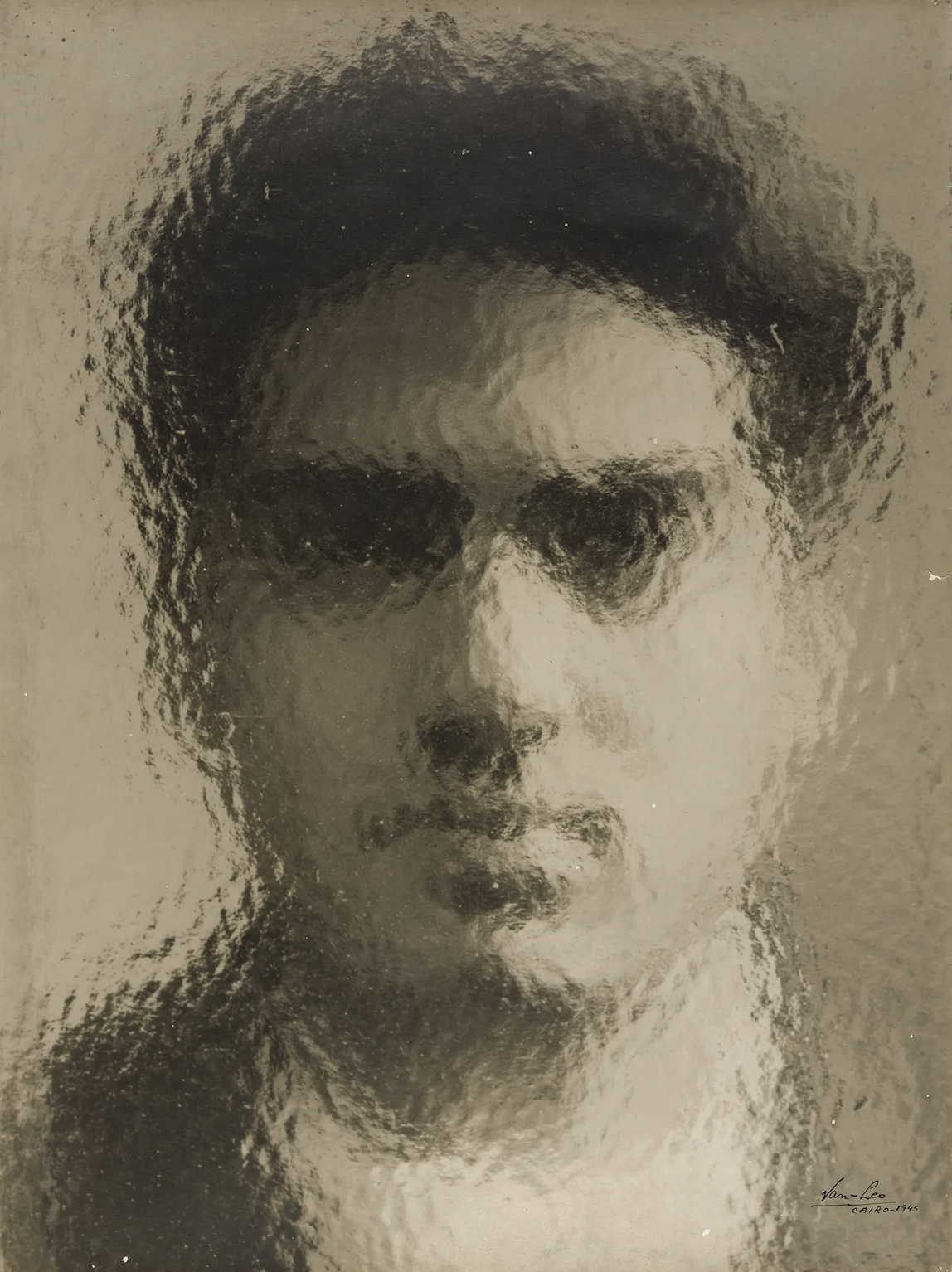

As for Van Leo, it is known that he has one of the largest collections of self-portraits ever taken. He took around 300-400 between 1942 and 1944. We could never know exactly why he did them, but it could be because he spent a lot of time by himself in his daylit studio. He also enjoyed playing characters and wearing whatever he wanted to wear.

He loved cinema. He wanted to go to Hollywood and live there but never did. He couldn’t leave his mother, sick and old, by herself in Egypt to try to become a photographer in Hollywood. He used to collect a lot of magazines and portraits of actors he loved. Photographing himself was in line with the glamorous studio portraits he was doing – experimenting with the light, and playing different characters. He had a performer in him, I think.

Paris was also a dream of his, to open a studio like Studio Harcourt. But instead, Angelo, his brother, left for Paris and opened a studio, and with him he took any possibility for Van Leo to leave. There was no one else to take care of their mother. After she passed away, Van Leo was already nearing 60 and felt like he couldn’t leave and start all over. He wanted to leave earlier and couldn’t.

One day, in 1998, when I was in Paris, he called me crying. He never cried to me before. “They came and they took everything,” he said over the phone

Losing the studio was losing a part of himself. It was his element. I vividly remember the studio. It felt like a theatre because there was a wooden platform where the talent would be photographed. It was one step and the floor creaked as you walked on it. There were also curtains behind it, so the moment you stood there, it felt like you were already a performer on a stage. You had to act, to become someone else. Every corner held memories of people he photographed and immortalised with his camera: Faten Hamama by the window, Rushdy Abaza, Omar Sharif, and later me next to the same window. His self-portraits too. The studio was everything to him.

“I don’t even have one pen, they just took everything in the studio and left,” he cried.

Van Leo donated everything to the American University of Cairo, where he was a student before. They came and took his archives. They took the table where we used to sit and have our tea. They took every camera, every frame. The whole studio was gone. They gave him 500 pounds every month and sent someone to care for him. I told him I was showing his work to people in Paris, and they were interested in buying it. “I have nothing left to sell. Everything had gone to the American University,” he said. “I’m going to die.” So I returned to Egypt for a few years and visited him at his apartment instead of the studio.

At his apartment, we would talk about Egypt, what he wanted to do, and his inheritance. He was considering getting married to have someone to care for him. We used to laugh a lot. He had a great sense of humour which he kept until the very end.

In his final years, his health deteriorated. He suffered from a hernia that couldn’t be operated on due to a weak heart. He also had a severe back pain. He would use a cane with the support of a corset to move around.

Without the studio, many people didn’t know how to reach him. Ambassadors, friends, collectors, and journalists would contact me to arrange visits to meet him. The American University began printing some of his work in their lab and sending the prints to him for signing. He would share the photographs with me again, retelling stories I’d heard countless times but they were always beautiful to hear.

He allowed me to rediscover his work. We spent hours going through boxes, uncovering images he never exhibited. I was too familiar with everything in the studio, but this was different. I remember the camera too. It was an old camera with a cable release connected to it. Without even looking through the lens, he would hold the clicker in his hand and before you knew it, the picture was already taken. You wouldn’t hear a sound.

It was very magical. He was someone from another realm. It felt like I was witnessing one of the last giants from that era in Egypt.

On March 18, 2002, his heart stopped working. He passed away without leaving Egypt. Without ever stepping foot in Hollywood as he always dreamt.

I was 29 and was in New York when the American University contacted me. They found my email and informed me of the news, knowing our closeness. I immediately changed my return flight from New York to Cairo and attended the funeral. It was in the Armenian cemetery in Heliopolis. There were only a handful of us there, perhaps five or six. By that age, he had lost almost all of his friends and had no family remaining.

I was one of four who carried his coffin into the grave, slowly lowering it. We scattered flowers and covered it with soil. I stayed until the very end. It felt right to be there for him, as I knew he would have wanted me by his side.

I couldn’t believe he was gone. Even now, I still feel his presence. Remembering him and recalling his stories makes me smile. I realised how rare he was and how fortunate I was to have met such a great man.

Van Leo photographed me five times over two years, in 1995 and 1996. I only photographed him once. We were sitting together, and I happened to have my camera with me. He sat by the window, and I took two or three pictures. That was it.

It wasn’t a whole photoshoot. We were just sitting at our usual spot by the window, looking out at the ever-changing city of Cairo, and I took that photo.

I love this photo I took of him because it has everything – the melancholy in his eyes, the little smile that he always had on his face. He was looking out the window, just as we always did, lost in thought. Sitting there at that table with him and sharing those quiet moments was unlike any other friendship I’ve had. That photo is filled with emotion for me.

Van Leo and I met at a unique moment in each other’s lives. I was just starting, and he was at the end. Yet somehow, we met in the middle, and a beautiful bond was forged in that shared space. A space filled with sunlight, the aroma of tea, and warm memories of Egypt.