News

Across ateliers spanning Milan, Cairo, London, and beyond, ICON MENA surveys the young voices forging fashion’s new frontiers. This emerging cohort of Arab designers represents a new generation that refuses to sever aesthetics from politics; that creates such that heritage and innovation go hand-in-hand; that eschews traditionalist postures and resists being boxed in. Clear-eyed, radically quixotic, wildly inspired, and surgically skilled: This is the shape of now.

OTH STUDIO: A Debut that Stopped the Room Cold

When OTH Studio staged its debut runway this past September, the atmosphere turned charged. Models crossed through pools of light in garments that, while moving, were in many ways unflinching. The finale’s last look bore, in searing red letters, the words ‘Free Palestine’ and ‘All Eyes on Lebanon.’“The room fell silent; it was almost sacred,” explains co-founder Khaled El Karout, who launched OTH studio with Mohamed Kraïem. “We faced pushback from the organisers, who didn’t want us to display it, but we refused to compromise.”

![]()

The show gave form to the animating force behind their practice: fashion as political consciousness. “That night, our hearts were with Gaza, where genocide had begun, and with Lebanon, [which was] under attack,” Khaled says. The studio shattered the idea of the stage as an insulated fantasy: “The vast majority of the audience were Westerners disconnected from reality… It allowed us to focus their attention, for at least a few minutes, on something beyond their personal concerns.”

This urgency was sown long before. “I discovered my passion for clothing back in high school, while searching for pieces that reflected my identity,” Khaled recalls. “But the pieces I wanted didn’t exist in men’s ready-to-wear.” Rather than shrinking himself inside misaligned clothes, Khaled took to his mother’s old sewing machine hidden in the garage. That singular night heralded his trajectory. Studies in Belgium and Paris followed, and his training was refined by stints in ateliers at Balenciaga, Balmain, Marine Serre, Chanel, until having his own studio became inevitable.

Kraïem’s route meandered further. Born in Sousse, Tunisia, he first pursued biology before his dormant creative nature prodded him into fine art. “Passionate about fashion and all forms of artistic expression, I also took up painting, which allowed me to exhibit some of my works internationally,” he says. After moving to Paris, he shifted toward sketching silhouettes. “In 2020, I met Khaled. Together, we founded and launched our own studio, OTH, where I now manage the artistic direction.”

![]()

These two sensibilities converged into a shared aesthetic language: structural but somehow still sinuous, daring with patchwork and provocative with shape. Even OTH’s oversized pieces seem to flatter. Their creations boast fluidity and dexterous chic, with silhouettes that are commanding and elegant but playfully lavish. “Our design language blends tailoring with unexpected, often subversive details, creating pieces that challenge traditional ideas of masculinity and gender,” Kraïem explains. “We mix sharp, structured cuts with fluid, draping volume, and elements borrowed from womenswear, crafting garments that feel both powerful and vulnerable.” Their SS25 campaign, all baby pink and silky, exalts a dynamic, feminine ornament that endears its wearer.

Their own biographies infuse the work. For Khaled, it is a way of negotiating his Franco-Lebanese inheritance. “Growing up between two cultures, I was constantly navigating questions of identity, belonging, and self-expression,” Khaled discloses. “My work is deeply informed by the idea that clothing can be both a shield and a statement, a way to reclaim space and tell a personal story.” Kraïem focuses on more tactile reconciliations: “I approach fashion as I would a space, paying attention to structure, texture, and the way elements interact,” he shares. His cultural grounding offers him a palette of patterns that he transposes into garments “that feel both rooted and innovative.”

![]()

As Arab designers, the two remain cognizant of stereotypes that shadow their field. “One of the biggest myths is that Middle Eastern fashion is only about luxury gowns, like Elie Saab or Zuhair Murad,” Khaled posits, stating that in reality, it’s about “real, active people” who run errands and live normal lives. “Can you imagine someone doing their groceries in a 70-kilogram beaded gown with an eight-meter train? Of course not. We’re seeing more designers breaking away from this cliche, especially with platforms like Fashion Trust Arabia spotlighting diverse talents.”

Next for OTH is a capsule collection orbiting the phrase ‘If my existence is a rebellion, then I am the revolution,’ followed by a studio expansion and an impending full collection in 2026. Decades on, the two hope that someone wearing their clothes feels emboldened to live without disguise.“Success for us is creating work that challenges norms and makes people feel seen, included, and inspired,” Kraïem says. “We want our work to give people confidence to express themselves freely and to remind them that difference is powerful.”

DANIAL SALIBA: A Palestinian Designer Cut From His Own Cloth

![]()

Milan may be saturated with couture houses and keen graduates, but Palestinian designer Danial Saliba’s vision, coloured by cultural inheritance, stands apart. His gravitation to design began early, though convention stifled his craft into an underground pursuit. “I’ve been passionate about fashion since childhood, though I initially practised design in secrecy due to social and personal constraints,” the designer tells ICON MENA. Opting for a public creative life came with immense personal sacrifice. “Choosing to leave behind a safe, expected life path to follow fashion was difficult; social and familial expectations weighed heavily on me. But it was the most liberating choice I’ve made.”

At Milan’s Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti, Saliba steeped himself in research and experimentation. Armed with faith and with his growing knowledge of the disciple, Saliba’s courage soon paid off in action. His graduate collection, Displaced Dreams, affirmed what instinct had long suggested: this was his calling. The collection carried imagery of barbed wire, branches, roots, and thistles, evoking migration and identity. Materials and silhouettes bore stories of personal and collective memory. “The collection became an emotional reflection on the idea of ‘home’ in times of displacement,” he explains. “I chose to centre my own migration story. It was emotionally difficult to expose that part of myself, but the result was honest… it taught me the power of vulnerability in design.”

![]()

Saliba’s work since has been a paradoxical confluence of fragility and strength. “I use garments as vessels to tell human stories, often around themes of identity, memory, and belonging. My design language plays with proportions and deconstructions to express what’s internal, not just external.” The designer’s influences span from the technical mastery of familiar titans like Georges Hobeika and Dior to ancient Arabic poetry and family photos. “I’m fascinated by transitional moments, whether in history or people’s lives. Those in-between spaces that feel fragile but are full of truth,” he says.”

For Saliba, being Palestinian is inseparable from design. “Growing up in a place filled with contradictions shaped the way I view fashion as both resistance and healing,” he explains. “I can’t separate my identity from my work… It’s an intrinsic voice that guides my design process.”

A meticulous selector of materials, Saliba suggests the symbolic aspects of creations should always be supported within the fibres of the fabrics themselves. “I’m drawn to fabrics that feel like they carry memory: raw wool, linen, recycled materials… I often use hand-pleating and subtle embroidery to convey unspoken messages, as if the garment had been preserved or mended from another time.”

![]()

Living in Milan, he resists being cast as a cultural ambassador or flattening his culture into embellishment. “I try to present my culture with depth and humanity, not as ornament or exoticism,” he affirms. “I want to show it as something living and evolving… Middle Eastern fashion is an incredibly rich, contemporary scene full of conceptual, experimental, and political work. Designers are creating from complex realities, and they deserve to be seen in their full dimensions.”

Saliba belongs to a generation of designers for whom artistic conviction is inseparable from a larger purpose. “We’re using fashion as a political and emotional tool,” he declares. “We’re not afraid to challenge tradition, power, or industry norms.” He explains that access to the digital sphere allows them to showcase their talent without conceding to the confines of a historically exclusionary industry. “We don’t need validation from traditional gatekeepers.” Looking forward, his measure of success is simple: “In ten years, I hope my pieces make people feel less alone,” he concludes. “That there is beauty in pain and dignity in remembering.

LEILA ROUKNI: The Art of Refusing the Expected

Moroccan designer Leila Roukni, founder and creative director of TALEL Paris, has spent the last seventeen years building a label that thrives on disobedience and scoffs at the predictable. Based in Paris, her design language is fluent in an inspired provocation, propelled by technical mastery and a commitment to elevated craftsmanship.

Born in France to Moroccan parents, Roukni left Dijon, a “small provincial town,” to study business in Paris. She honed her expertise in the industry’s leading ateliers, training within Chloe, Isabel Marant, and Saint Laurent. “That journey truly trained and shaped my sharp eye for accessory design,” she says. “With a philosophy that transcends expected design prerogatives and pushes existing boundaries.” But over time, she grew wary of “standardisation”: the same craftsmanship, same products, same designs, same colours. I didn’t relate to that and wanted to offer something different. Now that I’m working for myself, I create purely out of passion and desire, with no compromises.”

![]()

TALEL’s debut, the Triangle Bag collection, sets the tone with its unapologetic angularity in response to this inertia. “It was the starting point of everything, Roukni recalls. “I designed this collection with all my heart, without expecting anything in return.” The pieces were born from Roukni’s keen eye and creative hunches, resisting market forecasts with a staunch vision of something timeless and avant-garde. “It was an instinctive and personal process, driven purely by passion and vision,” she shares. “Today, this collection holds a special place for me, as it encapsulates the essence of the brand.”

This refusal to court expectation remains central to Roukni’s brand. Even now, she’s in pursuit of the next shape to break, hinting at expanding TALEL beyond leather goods into home items. “TALEL has always been more than just a leather goods brand. It’s a creative label, and this new project will allow me to bring the signature design philosophy into a new space.”

![]()

For Roukni, design is inseparable from ideology. “I would describe my design language as a celebration of freedom and disruption,” Roukni declares. “At TALEL, we believe in breaking away from the conventional, questioning norms, and challenging the status quo. The designs are an invitation to embrace individuality and nonconformity.” The sense of novelty Roukni strives for in her work is intended to be felt from all sensory angles, pieces insisting on a visual, but also a physically felt individuality. “I create pieces that not only look different but feel different.”

Roukni’s creative founts and muses shift fluidly: “Primarily, I draw inspiration from the streets: the energy, the movement, the textures. I also look to art, the automotive world, and my rich Arab culture, which is a constant source of inspiration.” She is galvanised from all angles: “Inspiration is everywhere and I try to stay open to it in all its forms.” While leather remains her primary medium, she is also experimenting with unconventional materials: “This season, for example, I’ve worked with hair, adding an unexpected texture and depth to the designs.”

While her heritage was inherent to her forming vision for TALEL, Roukni refreshingly avoids treating her heritage as a selling point. “I’ve never felt pressured to represent or explain my Arab culture through my work, but it’s always present, whether I’m conscious of it or not,” she clarifies. The designer’s refusal to reduce ‘Middle Eastern fashion’ to a narrow definition is pointed. “The idea that it’s only about traditional craftsmanship is a limited view… There’s so much more to it. The fashion scene here is rich, diverse, and constantly evolving. It’s important to move away from the stereotype and recognise that it’s a space where bold, cutting-edge ideas are shaping the future of style.”

![]()

Remaining faithful to her vision has not come without difficulty. “The hardest decision for me has been staying true to my creativity, even when it meant stepping away from the commercial and business side of things,” she reveals. “I’ve designed models that are strong, unconventional, and not always easy to sell. But in the end, I felt it was essential to stay true to what I believe in, trusting that the right audience would eventually appreciate the uniqueness of these designs.”

TALEL’s slow fashion ethos reinforces that stance: handmade in limited runs, marrying Italian craftsmanship with Parisian design. Now stocked by Kith, Printemps, and Galeries Lafayette, TALEL was also named a finalist in the 2025 Fashion Trust Arabia Prize for accessories. The brand’s existence is a reminder that independence in fashion is an act of persistence. “It’s about finding the balance between staying authentic to my vision and hoping the market will catch up.” When it does, she will already be several steps ahead.

Serag Elmeleigy: Through the Canal, Against the Current

![]()

When Serag Elmeleigy graduated from his international development degree in May 2020 at the height of the pandemic, the world was shut down, and his career plans with it. The Egyptian Iraqi designer had no formal training, only a certainty that clothing was the language he wanted to speak. “I took active steps to divert into fashion by learning all I could and getting a foot in the door with Talal Hizami at Pacifism,” he recalls. Teaching himself to sew and pattern cut, he produced samples and refined his skills with Rav and Parv Matharu at Clothsurgeon on London’s Savile Row.

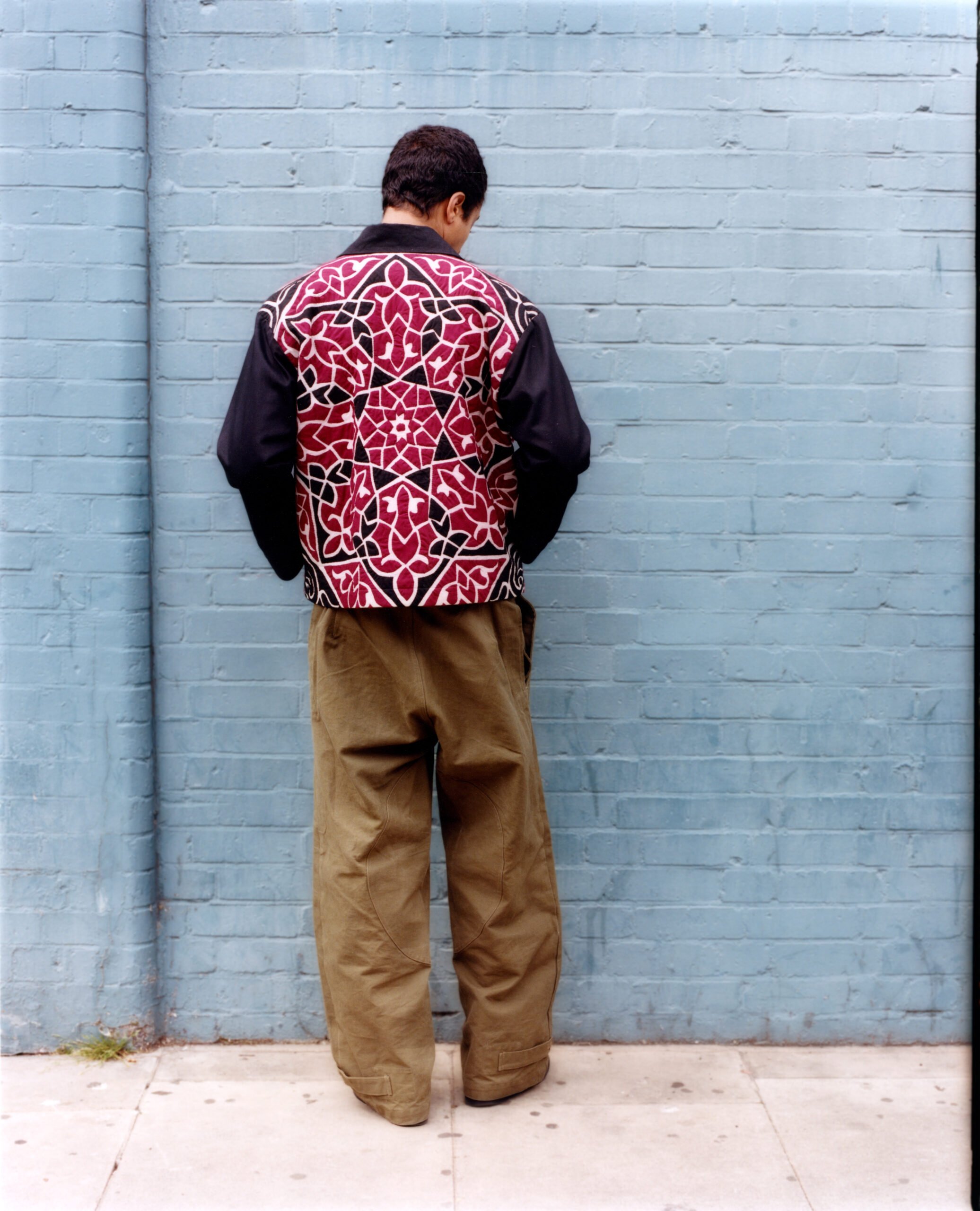

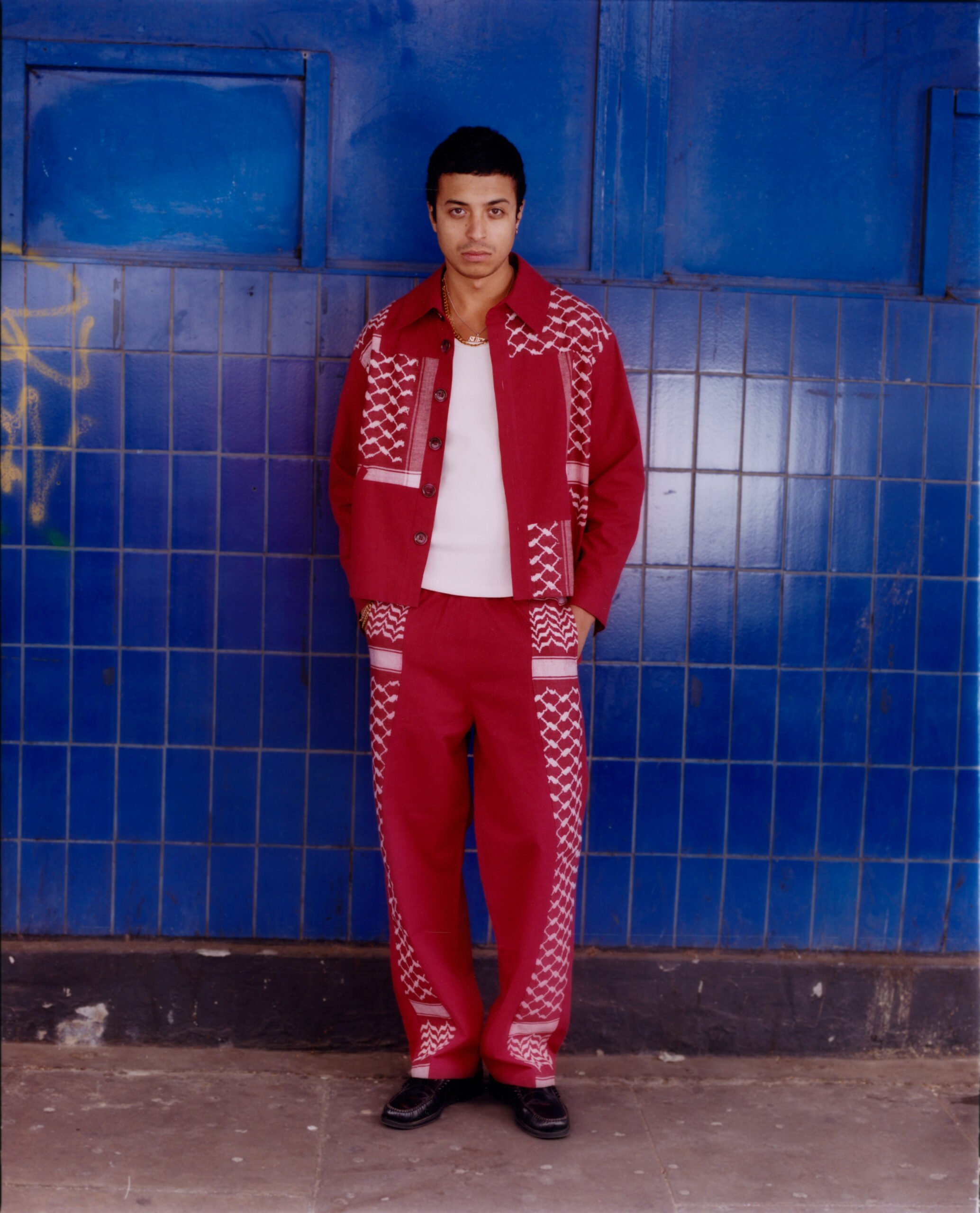

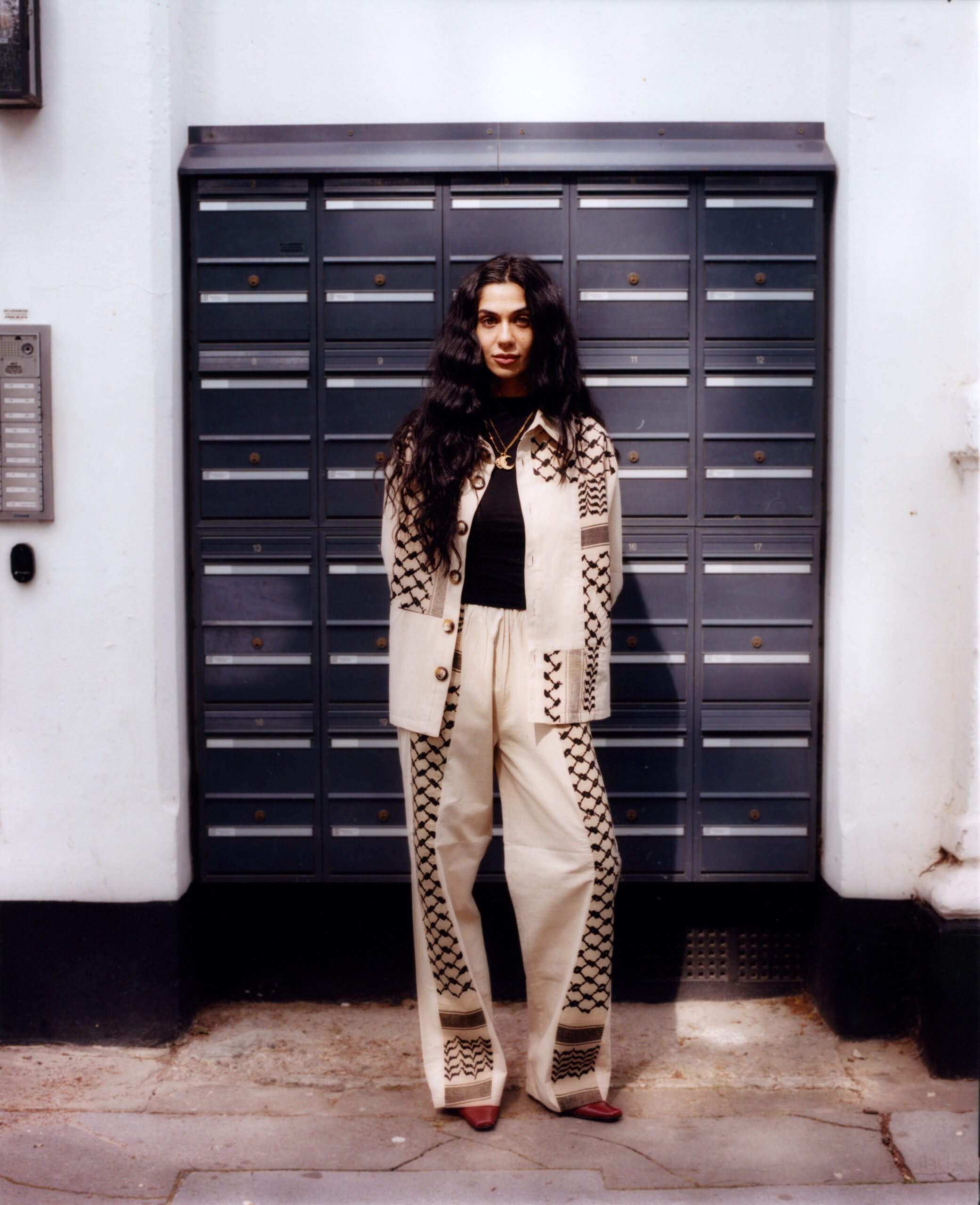

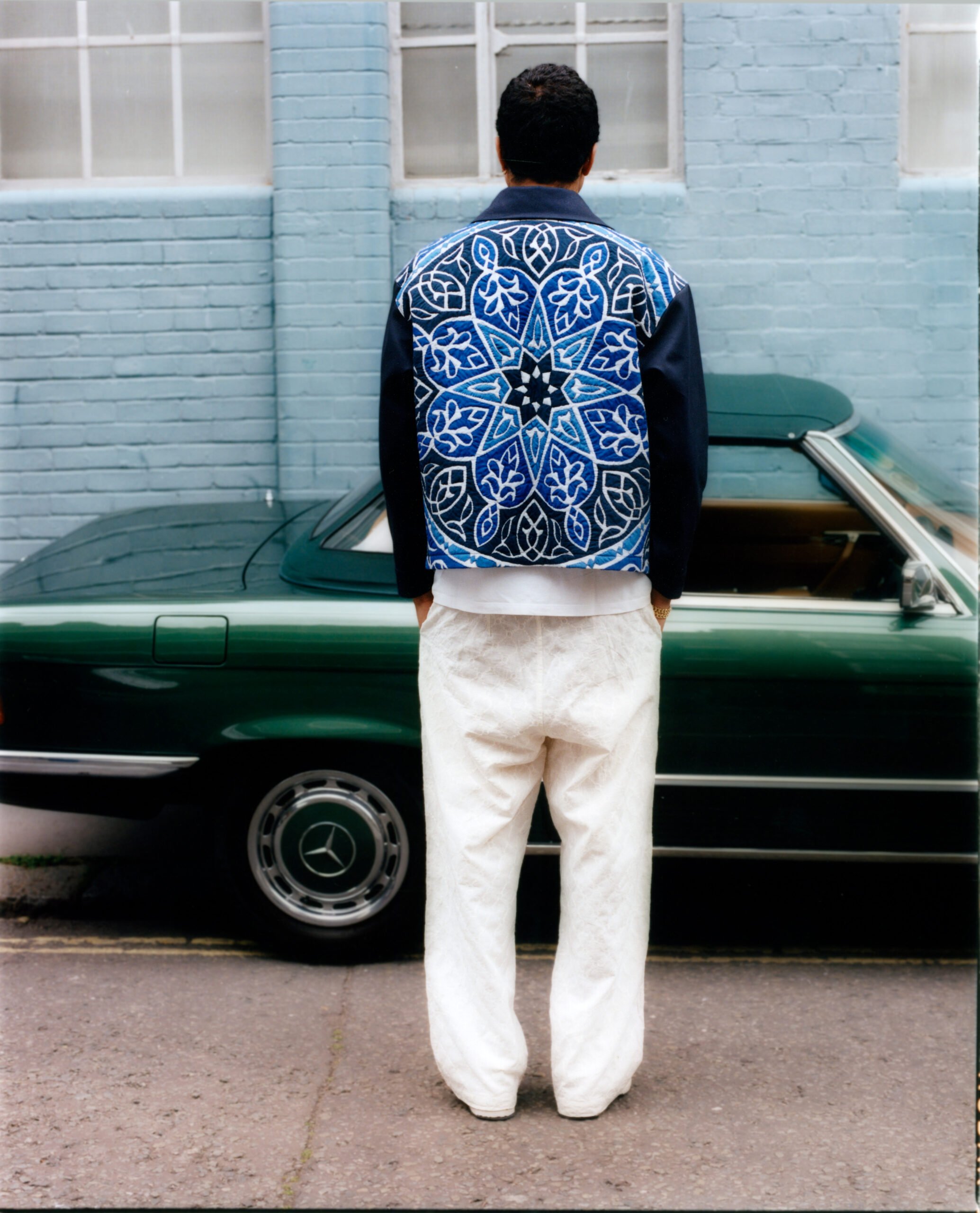

Now, Elmeleigy runs Suez Studio, a London-based label reinterpreting craft from across the Arab world. Named after the Suez Canal, the brand declares its motto and intention: “a passage through the Middle East.” Its aesthetic pulls on ’90s nostalgia, a sort of streetwear pragmatism, relying on the tactile richness of regional textile traditions.

His earlier collections breathed symbolism, with keffiyeh jackets cut into thirty-six-piece patchworks, or outerwear made from repurposed Khayamiya tent panels. His latest work teeters towards infrastructural themes. The forthcoming AW25 collection shifts the bulk of its production to Cairo. “We are working closer with our Khayamiya artisans and also working with the amazing women over at Threads of Hope Cairo, who specialise in handicrafts,” he reveals. A centuries-old Egyptian applique craft, Khayamiya can sometimes take months to complete.“We’ll be setting up a production system that is much more fluid and gives us much more creative freedom, incorporating artisans’ work while creating collections as opposed to individual pieces and small drops.” Designer Habiba Sawaf has been instrumental to the process, assisting both in design and on-the-ground production.

Despite steep logistical hurdles—finding the right factories, navigating Cairo’s manufacturing scene—the fruit it bears feels worth it. “This collection explores these crafts, and all the pieces will have some form of artisanal work on them,” he says. “With the rise of AI, we’re really looking to inject more humanness into all our pieces, embrace the slow and tell that rich history of craft that Egypt has to offer.”

Suez’s design language reworks regional textiles into large gestures and smaller interventions, like turning Khayamiya pillowcases into crescent-shaped outerwear. References range from vintage garments to Baghdad’s Bayt al-Hikma. Inspirations array across the maximal craft of Kapital to the tactical wit of Margiela. “I feel there’s synergy between Japanese fashion and what the Arab world of fashion can be, use of crafts, patterns, and interesting fabrics.”

He avoids synthetic fabrics where possible, favouring natural textures, but experiments with techniques like ajour, a hand-threaded laddering method. While his Arab identity once defined Suez’s work explicitly, this approach has now cooled to subtlety. “Simply by using fabrics made in Egypt, we are celebrating the culture,” he says. But Elmeleigy and his team decided to stop working with the keffiyeh so as not to devalue its meaning through commercialisation. “With the ongoing genocide in Palestine, we felt that it was time to stop…. We respect it so much and know what it means to people.”

![]()

Elmeleigy resists cultural pigeonholing. “As you create garments that revolve around your culture, people can start to put you in a box, and so I’d like to design all sorts [of pieces] as I get older,” he shares. “There is a lot of appetite from diaspora and also locals who want to see their culture in clothes in a certain way.”

Success, for him, is survival and connection: “To still be around in 10 years would mean we did something right,” he concludes. “We want to foster a community that feels seen by the brand, that appreciates the slowness and craft. When they wear our garments, they know a lot of time and care was put into it.” Already worn at weddings and award ceremonies, Suez garments are designed for special moments. Still, the designer insists on staying close to the workbench:. “There’s no better feeling than being hands-on, either on the cutting table or sewing machine.”

Among emerging peers like Medina, Studio Sabbas, and Sicander, Elmeleigy is energised by this generational profusion of young artists. “More competition means more innovation, which will be better for everyone,” he argues. Unlike older generations, this one operates in a world where organic social media content can bring years of progress in a single viral moment. Elmeleigy invokes young designers to make good use of this new moment in time: “We’ve been told and shown that the path in front of us is very possible, so go for it!”

Zeid Hijazi: Arab Futurism in Dystopian Form

Zeid Hijazi’s work is a composite of all the facets that define him: ancient folklore refracted through dystopian vision, Palestinian identity forged in London’s fashion establishment, and rebellion sharpened by persistence. His eponymous brand, launched shortly after his graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2024, already commands an attention larger than its years, interrogating what it means to invert Middle Eastern historicity into a futuristic realm.

![]()

Admission into CSM, famed for its selectivity, did not come easy for the Palestinian-born, Jordan-raised young designer. “I am not sure if it is considered a creative risk, but I had to prepare for three years before entering Central Saint Martins,” Hijazi discloses. “The acceptance rate is around 4 per cent, so I had to apply every year for three years until they offered me a spot, which changed my life forever. I don’t regret that risk.” He ascribes this resolve as a cultural trait: “Us Arabs, we are stubborn and want to be the greatest at everything. The word ‘no’ does not exist in the dictionary, and that is the mindset that I have while I am designing.” That stubbornness propelled him to a moment that still grounds his practice: exhibiting a piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where he became the youngest and first Palestinian designer ever shown. “It came at a moment when I was questioning a lot of things, and it was meaningful because it felt like an answer from the universe, a reminder that my story is just as worthy of being in a museum.”

He describes his design language as “dystopian, but from a Middle Eastern perspective… anti-Elie Saab,” meaning “no embellishments” and no “shiny.” Against stereotypes of ostentatious Arabs “dripped in gold fur,” his work favours sharp silhouettes, shadowy palettes, and jarring proportions. His clothes conjure a fictional world that merges Arab futurism with gothic subculture, folklore with aesthetic dissent. “It’s posing thought-provoking storytelling about the mysteries of a futuristic yet dystopian Middle East, while incorporating Middle Eastern craftsmanship with couture elements.”

![]()

Architecture and cult films are creative touchstones, speaking to his fascination with the surreal. The influence of Chilean-French filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, whom he jokingly calls his “father in a past life,” manifests in Hijazi’s penchant for the esoteric. His garments feel cinematic, tactile, straddling ancient and speculative worlds.

Rebellion is the designer’s throughline. “What’s something my generation of designers is doing that older ones couldn’t? Rebelling,” he answers simply. His vision rests on alternative futures, constructing a space where Arab identity is not at risk of reductive cliches or tokenism; rather, it becomes a lens for reimagining fashion itself. “Fashion is really unpredictable; it’s nothing like choosing to be a doctor and having that career sustain you for the rest of your life. I made the decision, though, which means I am happy.” Optimism in the face of such volatility is one of Hijazi’s more endearing radical qualities.

Hijazi is now working on his sophomore collection, continuing to build on an avant-garde future. “Success, for me, is being able to practice my craft with a full heart,” he declares. “It is, in a sense, to create freely and with joy, without being crushed by something that would make me sad, like the news, an argument, or whatever. But also, I want to be creative of a big fashion house. That is also a success.”

![]()

Balancing that private measure of joy and the public ambition of leading a house is perhaps Hijazi’s most potent contribution: the refusal to let one eclipse the other. His garments remind us that dystopia and beauty, defiance and craft, heritage and futurism can exist in incredible confluences. His work, like his journey, insists on possibility; on a future that belongs to him, and to all those who see themselves in it.