News

In his book Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said explores the connection between cultural narratives and imperialism throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. He argues that the ability to shape narratives, to decide what is remembered and what is forgotten, is a powerful tool used by imperial powers to maintain their dominance over the people and cultures they besiege and control.

Usually, this control of memory takes the form of overt, colonial imposition. Banning books, customs, and languages. Whitewashing histories, cultures, and religions. Concerted and committed efforts to erase cultures, identities, and the very notion of indigeneity.

However, these erasures aren’t always loud. Sometimes they take the form of silence. They are found in locked archives, museum labels that do not mention where objects originate, and structures left abandoned to time. Often, they wither, with liberalisation, with emigration—with “development.”

But the effect is the same. What was once visible becomes obscured. What was once public becomes private. What was once sacred becomes property. Yet memory still leaks through its cracks. Even in the most carefully constructed expungings, traces linger. And the fight to recover them becomes a fight not just for memory, but for justice. For autonomy. For imagination.

Across the Global South, artists, archivists, filmmakers, and architects have long been caught in this struggle. Their work speaks not only to what’s been lost but to what was never truly gone in the first place. Some of it has been buried deliberately. Some of it survives in fragments, passed hand to hand. And some of it has simply waited—quietly and stubbornly—to be seen again.

HIDDEN

“There’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless.’ There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.” — Arundhati Roy

Some things are hidden to protect them. Others are hidden to make them disappear.

Across the world, in countries whose borders have been artificially constructed by the very empires that ravaged them, art, film, literature, and political memory have been deliberately suppressed—not destroyed, but displaced, scattered, and fragmented. Sometimes, it’s authoritarian regimes and occupying powers, usually, those same empires, that hide them. Sometimes, it’s the archive: a place that promises safekeeping but just as often acts as a vault, sealing away what might be too disruptive, too volatile, too radical.

In 1982, during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, Israeli forces looted the PLO Research Centre in Beirut. Among the items taken were reels of Palestinian film, as well as poetry, images of daily life, revolution, land, and longing. These weren’t just political documents; they were memories of resistance. They were visual affirmations of a people asserting their right to exist—on their terms, on their land. Most of the footage was never recovered. Some say it sits in military archives; others believe it was destroyed. But fragments remain.

Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Aljafari has spent much of his life tracing those fragments. In A Fidai Film (2024), he reclaims part of that erased history, mixing salvaged footage into a memory-work that puts the brutality of political sabotage, theft, and erasure front and centre. Aljafari explains why Israel refuses to return the footage—the fragments that collect dust in archives and the homes of Israeli academics—in no uncertain terms. “They want to control everything. They want to control even the image of the people about themselves,” he says. “It’s an obsession of every colonial power—to distort the image, to distort the history.”

There is a similar urgency in The Flowers Stand Silently (2024), a haunting, wordless short film by Greek-Lebanese-Palestinian filmmaker Theo Panagopoulos. After discovering a forgotten archive of silent reels documenting Palestinian wildflowers from the 1960s, he reassembled them into a meditative, flickering testimony of life that somehow endured, even without names or narration.

Hiddenness, in these cases, is not just absence. It is what cultural theorist Tina Campt calls “listening to images”–a way of attending to what remains unspoken or unseen, especially in archives shaped by erasure. In Listening to Images, Campt writes about the power of Black and brown subjects in historically dismissed photographs not as passive victims of imperial documentation, but as quiet rebels who refuse to disappear. That idea sits at the core of so many Global South memory projects: the refusal to vanish, even when unseen.

Some archives are hidden behind state repression. Others are tucked away in basements, private collections, and hard drives. In Iran, for instance, entire collections of art, masterpieces by Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh, Andy Warhol, and Jackson Pollock, worth an estimated $3 billion, remain shrouded in mystery in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. These works were acquired during the Shah’s brutal reign but have been kept largely from public view since the revolution. They sit in a kind of suspended time: officially owned but culturally disavowed, guarded by a state unsure of whether to flaunt or forbid them.

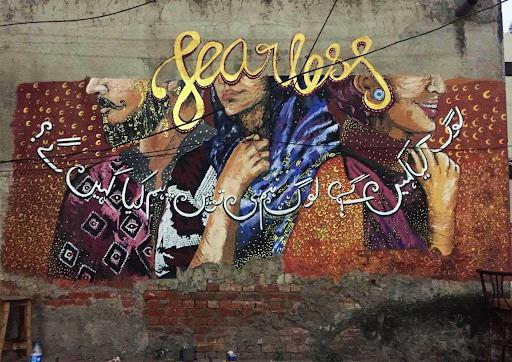

Elsewhere, underground art scenes have had to develop entire aesthetic languages of concealment. In Russia, queer artists have responded to state censorship with works that mask, distort, and encode, operating in visual codes legible only to those who know how to read them. Platforms like O-Zine and Drag Zina circulate queer narratives through collage, coded imagery, and community language. In Pakistan, The Fearless Collective creates public murals that quietly subvert patriarchy and militarism, while artists like Poor Rich Boy weave veiled criticisms of authoritarianism and cultural decay into indie rock. What can’t be shown finds refuge in zines, murals, secret performances, Telegram channels, and living rooms. But the art never stops.

It is power that decides what remains on the surface and what gets submerged, what is archived and what is officially forgotten. But the cover doesn’t stay that way forever. What’s been buried can be unearthed. And increasingly, it is artists, activists, and often ordinary people, looking to unearth their own complicated identities and histories, not governments, not institutions, who are doing the digging. It is them, us, who are reassembling lost footage and reclaiming family photo albums. We are the ones who pull memories out of the rubble and bring them into the light.

There’s something quietly radical in this: the idea that fragments can be enough; that we don’t need completeness to tell a story; that sometimes, a single surviving reel, or a photograph, or a painting behind a locked museum door can carry the entire weight of a culture refusing to die.

But for everything that is left behind, there are twice as many that are taken. Archives are looted. Artefacts displaced. Memory torn from place and context. What begins as concealment is, over time, overwritten by theft. And much of what is buried cannot be recovered because it has been stolen.

STOLEN

“To plunder, to erase, and then to display; this is how empire narrates its conquests.” — Nada Shabout

The irony of the theft of culture is that it is often presented as everything except for what it is: “preservation,” “humanitarianism.” This is how museums justify their possession of looted artefacts and how empires frame the plunder of the Global South: not as seizure, but stewardship. But to steal culture is not only to strip a people of their past; it is also to rob them of their present and future. And that theft is rarely limited to what can be put behind glass and hung on walls.

In fact, colonial plunder did not end with independence; it merely shapeshifted. Today, it continues under the banner of soft power and global capital: through copyrights, film festivals, and the NGO-ification of local art scenes. It persists through the external funding of curated narratives, through the exploitation of labour, through the appropriation of culture, or simply, through the decontextualised repackaging of trauma for Western consumption. What was once seized by force is now often taken under the guise of access, opportunity, or development. The colonists may not still be around, but the West still owns the means of cultural production. And it still dictates the terms of legibility.

Last year, filmmaker Mati Diop premiered her documentary Dahomey, chronicling the return of looted royal artefacts from France to Benin. The film, which went on to win the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, turns a critical eye on the celebratory discourse of restitution. In doing so, it shifts the focus from the gesture of return to the violence of theft. Partial restitution, after all, cannot undo dismemberment, much less neo-colonialism and imperialism.

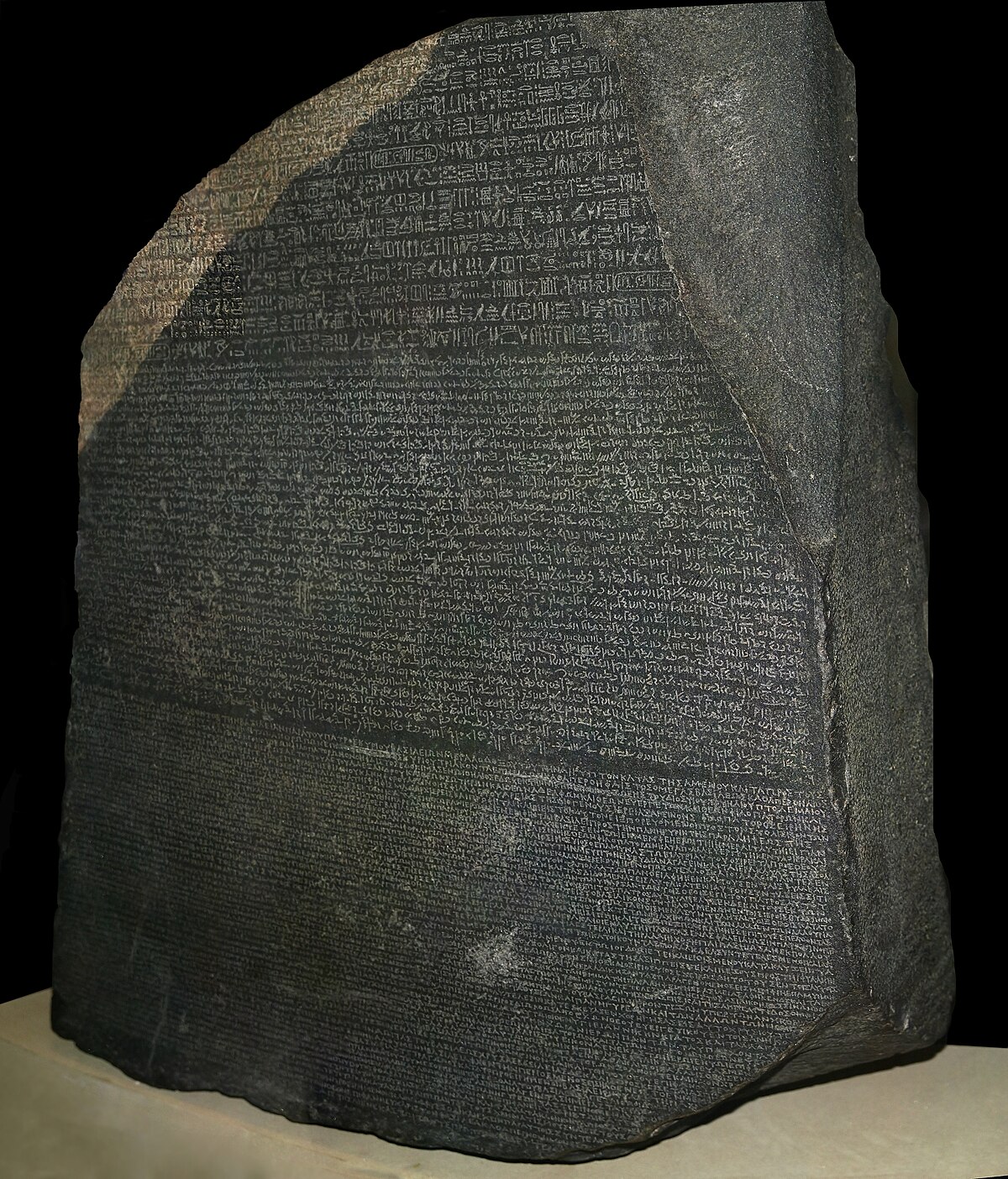

Across the Global Majority, countries have been demanding the return of cultural artefacts stolen during colonisation. Egypt’s long-standing campaign to recover the Rosetta Stone, stolen by Napoleon’s troops and later seized by the British, has gained momentum in recent years, part of a broader reckoning with the legacy of imperialist museums. British Egyptologist John Ray has observed: “The day may come when the stone has spent longer in the British Museum than it ever did in Rosetta.”

But the theft of Egyptian heritage runs deeper than artefacts. A wave of Egyptian modernist architecture, designed in the 20th century, has also been systematically erased, neglected, or claimed by foreign developers as the state prioritises spectacle over preservation in recent years.

In Cairo, many buildings that once embodied a distinctive modernist Arab vernacular have been demolished or refashioned beyond recognition. Working-class communities along the Nile were demolished to make way for luxury developments in the Maspero Triangle. The Mogamma el-Tahrir, once a towering symbol of state bureaucracy, is being transformed into a luxury hotel—its history buried beneath speculative real estate interests. Not only are such structures removed or repurposed, but they are also rarely archived, mapped, or taught. Their erasure is both physical and epistemic—a seizure of both form and memory.

In Syria, too, cultural destruction and extraction have walked hand in hand. The civil war did not just ruin cities and the lives of millions of Syrians; it also shattered collective identity, history, and cultural continuity. Among the war’s underreported tragedies was the looting and trafficking of ancient artefacts, many of which were smuggled through black markets and ended up in private collections across Europe and North America. Palmyra, a major Silk Road hub and home to some of the Middle East’s most important Greco-Roman ruins, was decimated by ISIS. Museums and libraries across Syria were bombed, gutted, and looted. A civilisational archive was torn apart. Razed. Erased.

But this erasure didn’t begin with the war. Long before the conflict, foreign archaeologists were often granted more access and authority than Syrian scholars themselves, a dynamic that turned ancient history into an exportable commodity. Theft is not just the physical removal of artefacts or the destruction of heritage by occupying powers; it is also embedded in the false belief that the West is better equipped to extract, classify, and preserve cultures than the people who live within them. It is a form of cultural embezzlement.

This is the paradox of visibility. To be seen is not always to be recognised. Representation from the Global South on global stages often comes with the flattening of context—a refusal to acknowledge the violence that shaped the work or the artist. Anti-colonial films are acquired by platforms like MUBI, which is financed in part by the very corporations facilitating Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Sudanese works are exhibited in London while artists in Khartoum are forced into exile. The South is visible, but not sovereign. Its creativity is welcomed only when it conforms to Northern frameworks, which often demand its depoliticisation. A striking number of “international” films about conflict zones in the Arab world or Africa are still directed by Europeans or Americans, and even stories of resistance are mediated, softened, and made legible for liberal audiences abroad.

What gets stolen in this global circulation of culture is the specificity of places. The knowledge systems, political histories, and spiritual inheritances that shaped entire civilisations are condensed and packed into neatly organised displays in the hallways of the British Museum. But artists, curators, and thinkers in the Global South are pushing back against these heists and erasures. In Egypt, groups like Megawra are mapping, restoring, and reimagining the architectural heritage of historic neighbourhoods. And across the region, new institutions are emerging that don’t just seek representation, but autonomy.

Yet such efforts remain on the margins. In a world where “development”—especially in formerly colonised nations—is synonymous with glass towers, luxury hotels, and shopping malls, entire communities are razed to emulate Western infrastructure, no matter the cost. Centuries of cultural memory are wiped out to make way for projects designed not for people, but for capital.

This is also theft: by financial institutions, local elites, foreign investors, and ruling classes eager to disown their own pasts. And often, even these “redevelopment” projects fail to deliver. Plans stall, before eventually being abandoned.

ABANDONED

“The politics of memory influence what is preserved, what is demolished, and what is newly constructed.” – Omar Harb

There is a kind of disappearance that is quieter than theft, and more subtle than concealment: abandonment. Things are not always stolen or hidden. Sometimes they are simply left to rot.

Abandonment—of culture, infrastructure, and identity—often feels passive or benign, but it is anything but. It is an act of withdrawal that carries its own violence. In our so-called post-colonial world, buildings, neighbourhoods, archives, and even entire cities have been forsaken; left to decay because they no longer serve the political or economic fantasies of those in power.

This is a condition that follows the end of the utopian hope of liberty. After independence struggles and revolutionary dreams comes the long dusk of structural adjustment, authoritarian consolidation, and neoliberal development. Abandonment is the afterlife of that harsh reality.

Consider Beirut. Once seen as the “Paris of the Middle East”—a description itself rooted in the flawed belief that the West is the benchmark for modernity and progress—the city has become an architectural palimpsest of modernist ambition and post-war neglect; a consequence of both maladministration and, of course, the Zionist entity wreaking havoc on the Lebanese people and the country’s infrastructure. Its unfinished hotels, bombed-out theatres, and housing blocks half-eaten by time all tell stories of ruptured dreams.

The Egg, once intended to be a dome-shaped cinema, remains in limbo decades after it was supposed to be built, a skeletal reminder of the civil war that halted its construction. Meanwhile, the Grand Theatre, a marvel of the 1920s, lies unused. Not far away stands the Murr Tower: a sniper’s perch during the war, now a towering relic of violence and political stagnation. For decades, it has loomed over the city, abandoned yet inescapable, a monument to a conflict never truly resolved.

Such sites aren’t abandoned by accident. They are sacrificed in favour of short-term capital and long-term control. After the war, the reconstruction of Beirut was handed over to Solidere, a private real estate company pioneered by then-prime minister Rafik Hariri. In the process, swathes of the city were flattened and privatised, and the buildings that weren’t destroyed were left to decay, either too historically loaded or too financially troublesome to rescue.

In this way, abandonment becomes a selective process in which what gets saved and what gets left behind reveals the underlying logic of power. It is a form of strategic neglect, of convenient obliviation. Lebanese architect and academic Omar Harb explains this in his paper The Erasure of Memory and Urban Identity in Post-War Beirut: “In post-war Beirut, architecture did not merely fail to preserve memory,” he writes. “The reconstruction of the city’s core employed an aesthetic ideology that can be best described as amnesiac: clean, stylised, decontextualised, and conveniently detached from both the scars of war and the vibrancy of pre-war life.”

Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city, offers another haunting example. The Rachid Karami International Fair, designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, was meant to be a crown jewel of pan-Arab architectural modernism. Its sprawling concrete structures embodied the spirit of post-colonial ambition, but the civil war stopped the project in its tracks. Decades later, it stands derelict.

The abandonment of spaces like Niemeyer’s fairground is more than a matter of budget or maintenance; it marks the abandonment of a vision, of the optimism of post-independence Arab socialism and international solidarity, which was buried by war, corruption, and the successive neoliberal regimes that had no place for such dreams. In fact, such abandoned structures are often found where revolutionary or collectivist ideals once took shape, before they were snatched away. In Cairo, workers’ clubs, cooperative housing blocks, and cultural centres of the Nasser era have been left to disrepair or replaced with malls and gated communities.

Elsewhere, abandonment coexists with occupation. In Jerusalem and the West Bank in occupied Palestine, homes left behind in 1948 and 1967 have been seized, resettled, and refashioned, their original histories erased by Zionist statecraft. The act of abandonment is forced; the vacancy is filled by colonisation. The shell remains, but the narrative is rewritten. In this sense, the architecture of abandonment also becomes a canvas for state violence.

And not all abandoned sites are physical. Archives, too, are forsaken. Films rot in storage vaults; manuscripts disappear in bureaucratic basements; oral histories are recorded but never catalogued. These absences are particularly tragic because a people without access to their memory cannot easily resist their erasure. Cultural abandonment, then, is not just neglect. It is also epistemic violence.

At the heart of it all is a simple but brutal calculus: if something no longer generates profit, legitimacy, or control, it is left to die. This is not unique to the Arab world. Across Latin America, abandoned infrastructure and unfinished megaprojects tell similar stories. In Brazil, Niemeyer’s own designs, once symbols of public imagination, now stand broken and empty. In Senegal, the now-abandoned Akon City—a gleaming “futuristic” city promised by the American-Senegalese star—remains an unfulfilled fantasy. Utopia sells, but rarely delivers. Across the world, abandonment is the detritus of failed promises and forsaken futures.

But abandonment can also produce something unexpected: resistance. Protesters often occupy neglected buildings, and communities repurpose and breathe life into forgotten archives. In Beirut, protestors during the Thawra of 2019 turned the Egg into a site of public dialogue and performance, and efforts by the yearly design event We Design Beirut have been made to transform the scars that the Murr Tower stands as a reminder of. In Bogotá, cultural collectives like La Redada and Casa B occupy disused spaces, transforming them into sites of radical pedagogy and memory work. In these moments, abandonment becomes an invitation to reimagine.

Still, it is no substitute for justice. Whether something is hidden, stolen, or abandoned, the result is often the same: a rupture in memory, a break in continuity, or a silencing of struggle. What is hidden can be more easily stolen. What is stolen is often never recovered. And what is abandoned is left to be hidden again. The cycle continues, and in it, history itself is put at risk.

So, the question is not just whether we can remember what was hidden or retrieve what has been stolen. It is also whether we are willing to repair and recover what has been abandoned. And, whether in doing so, we can rescue not just the structures, but also the visions they once held.