News

“I just love our accent!” Sara exclaimed, interrupting my first question excitedly. I realised it was the first time in my seven years of journalism that I’d interviewed someone from my hometown, and the familiar cadence of our native dialect was a surprising comfort.

We hadn’t spoken in years. We both come from Sweida, a small town in south Syria, where everyone knew everyone. We’d shared a digital friendship as teenagers, exchanging whatever poems and artwork we’d be working on. Then one day towards the end of 2015, Sara messaged me, “I’m leaving for France and throwing a goodbye party. I’d love to see you there. We didn’t get the chance to meet closely.

I went to the party and said goodbye to her.

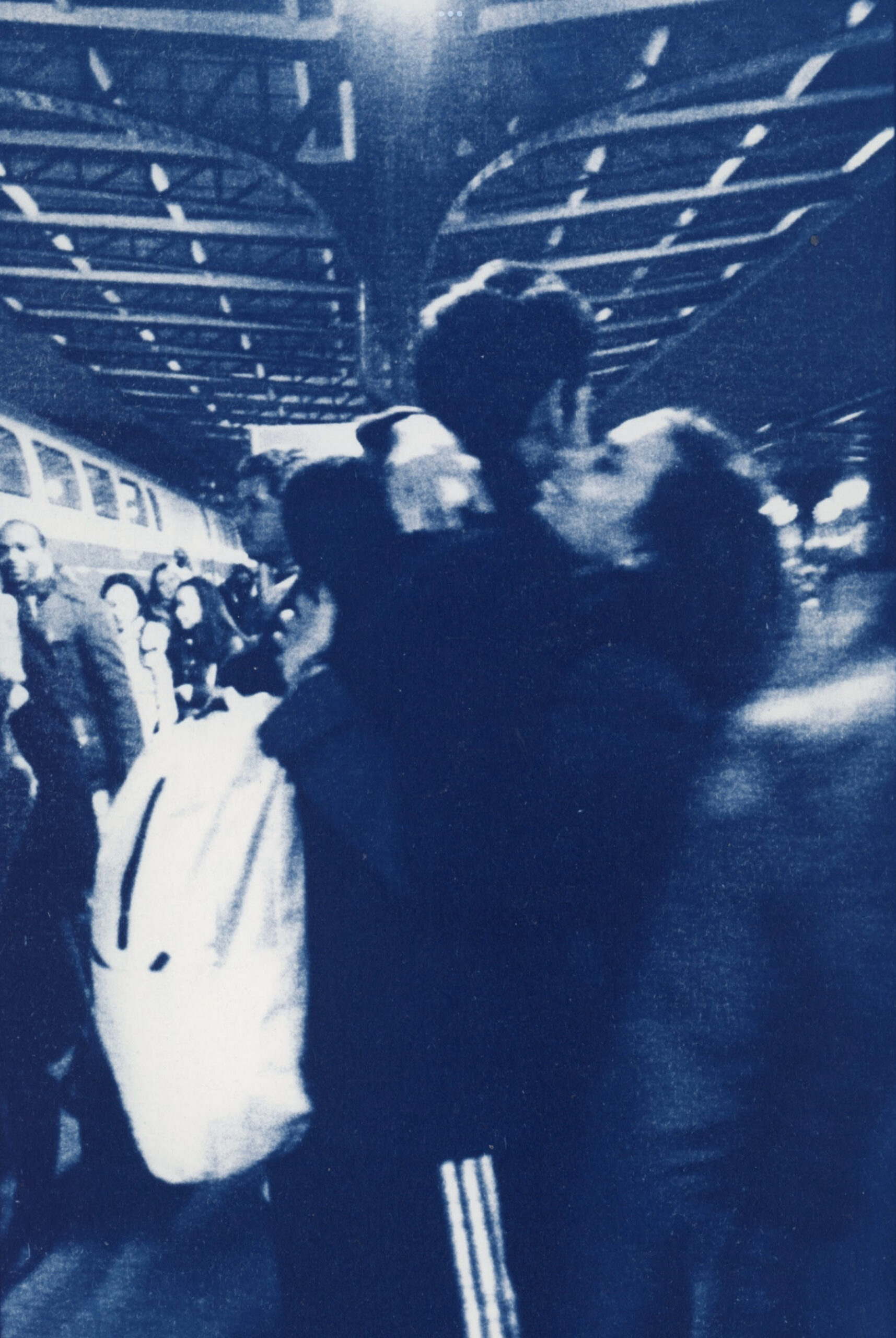

After that, Sara would share her journey with me every once in a while. She’d update me on their stops from Syria to Turkey, then Greece, and finally, France, where she studied in an art school and later completed a Master’s degree in animation cinema from L’École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Paris (ENSAD).

Over the years, I followed Sara’s journey online with immense pride. Witnessing her blossom and transform her experiences of discrimination and struggle into something inspiring was truly remarkable. Perhaps my hometown bias plays a part, but there’s no denying she’s an artist who managed to pave her own path with lots of determination and patience. Her artistic practice has evolved across various mediums, and while defying easy categorisation, her work consistently centres on telling a story.

When asked to describe her art, Sara replied, “Honestly, I’ve been grappling with this question myself lately. It’s been challenging to fit into certain artistic and institutional conversations here. I struggle with how my work is presented, especially since it revolves around exile which is my personal story.” Although she was always drawn to art and photography growing up, Sara began her studies in architecture in Syria due to limited opportunities in the arts. Relocating to France allowed her to fully embrace her passions, drawn by the expanded possibilities, education, and institutional support she found in Paris.

“During my studies here,” she says. “I realised my true passion was storytelling, not the form itself. We would learn about shapes, lines, and colours, and I’d be captivated by the story and content. Even with simple techniques, I felt a strong connection to authentic expression. At first, my photography was artistic, staged, and disconnected from reality.”

This trajectory shifted with “Towards A Light,” an archival project that began as an attempt to dig deeper into her memories to understand her journey and herself better. Years after settling in France, Sara was grappling with a profound sense of dislocation and a growing loss of identity and place. A haunting limbo between “here” and “there,” consumed her. To compound her distress, her memory began to falter, often blanking on memories of her life in Syria. Nightmares and anxiety resurrected haunting images from her stop at Turkey and the sea.

Sara realised that in order to move forward, she needed to confront the past. She began to meticulously document her recollections, in an attempt to retrace her journey from the moment she left Syria. As she delved deeper, forgotten memories surfaced, and she stumbled upon photographs she didn’t consciously remember taking.

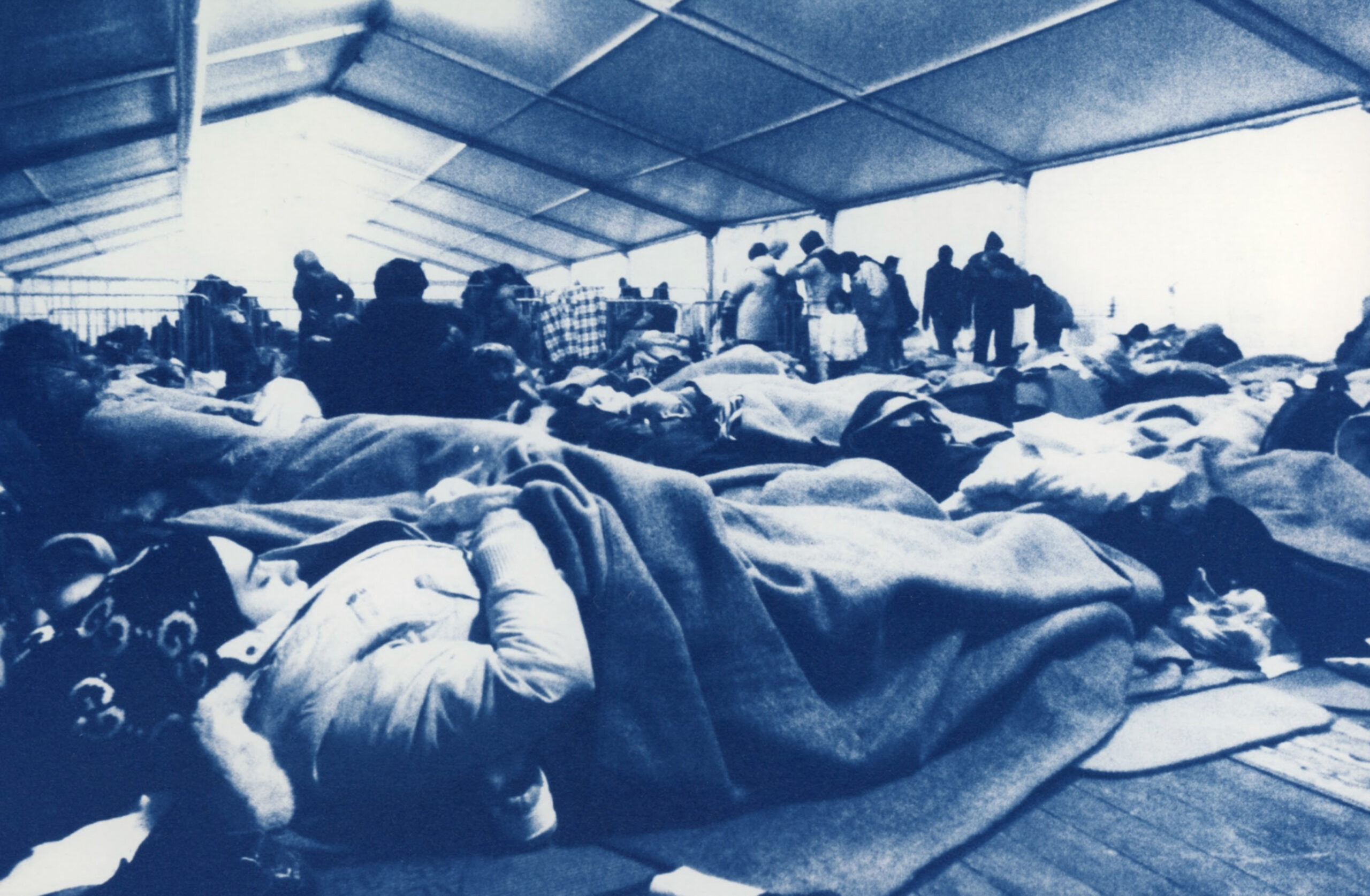

During her stay in Turkey, while attempting to get to Greece with her twin brother Ahmad between December 2015 and February 2016, Sara refrained from taking any photos. “My father urged me to take pictures, to record everything,” she recalls. “But I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Those weren’t memories I wanted to preserve. Forgetting was much more important to me than documenting during that time. We were going through so many difficult emotions, and it was hard to accept our reality.”

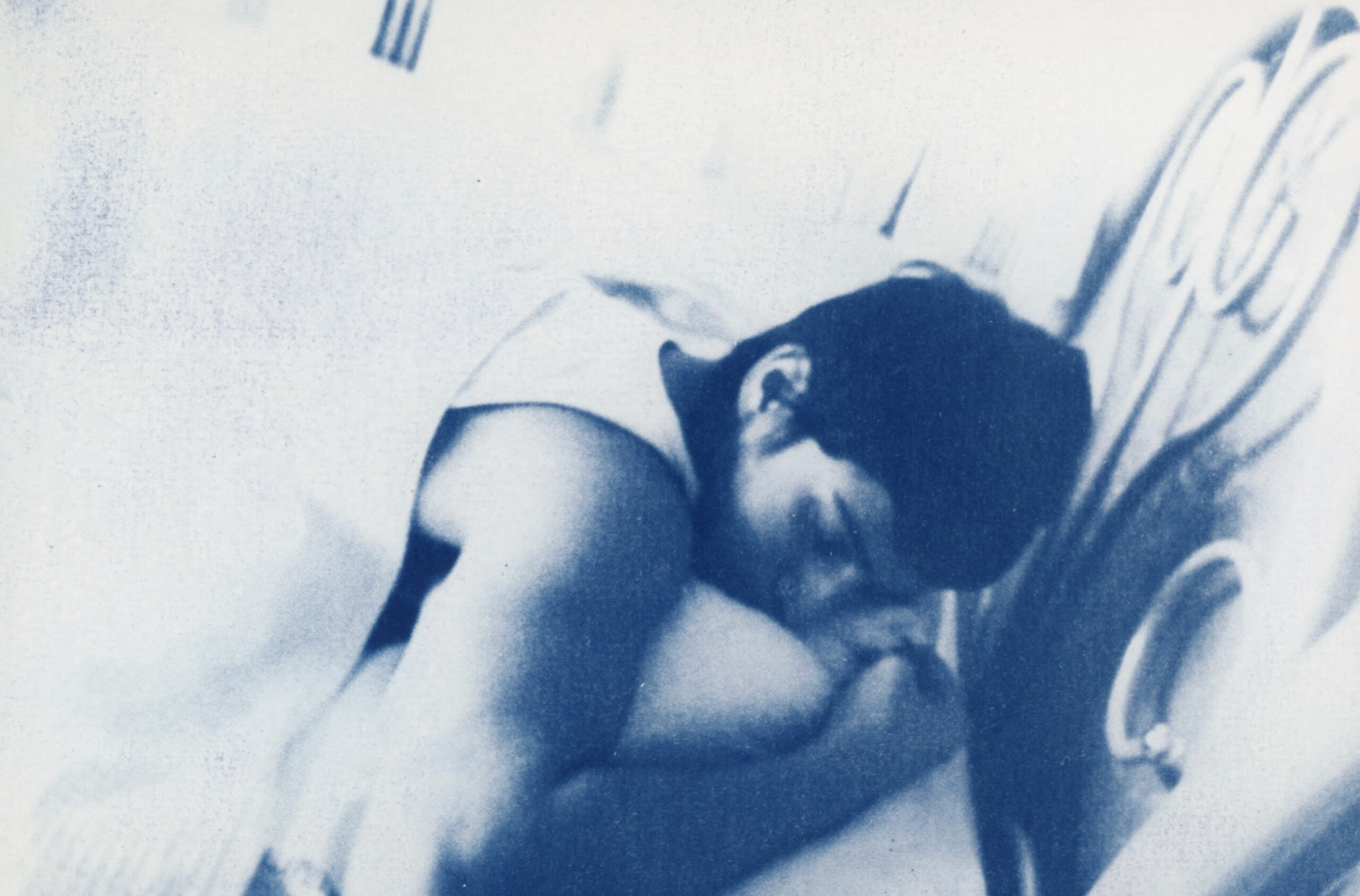

Sara however did end up taking pictures, but not with the purpose of creating art or making a statement. They were casual photos sent to their family and friends on WhatsApp groups – mostly selfies or photos of what they were eating, or of Ahmad sleeping. “And then there were also the touristy photos,” she reminisces. “Where we were like, ‘Hey, look at this beautiful view! Take a picture of me here.’”

Using Cyanotype, a photographic printing formulation dating back to 1842, the photos were given a stronger treatment. The process also turned the photos blue, echoing the water that is so central to the refugee experience. She paired these photos with her own writing, and the result was “Towards A Light”, a project that would later be exhibited at Palais de Tokyo.

A driving force behind Sara’s photography and, perhaps, humanity as a whole, is the fear of forgetting. As a coping mechanism, Sara obsessively kept a diary for a year after arriving in Paris, recording even the most trivial details of her daily existence. This compulsion eventually transformed into anxiety, propelling her towards photography and documentary filmmaking.

“My relationship with photography is special because I forget and I’m afraid of forgetting. Photography allows me to steal from time. I feel like it’s impossible to lose something I love once I’ve captured it in a photo. Even if it’s just a corner of a street, or a cracked wall – things that allow me to carry them with me. I live through photography. Sometimes I force myself to put the camera aside and let time steal from me.”

Unconfined by form, Sara also experimented with short films. Her most recent is “3350 KM”, named after the distance separating her from her father who remained in Syria by himself. “As I said, photography is the tool that allows me to stop time and control it. The same goes for filmmaking. The film definitely reflects a political situation and reality. It’s about a bigger story – an experience that represents the experiences of many people, how we live with screens, with family separation, in exile.”

The film follows a call between Sara and her father, with footage of their house which she recorded during their video calls. The house feels cold, empty, and lonely with him alone there. This pixelated virtual experience is something most Syrians go through when talking to family abroad. It instantly reminded me of my calls with my parents back home, often asking them to repeat themselves because due to the poor connection. Ironically, I rushed to finish this interview a day before going back to Syria, knowing I wouldn’t be able to do it online there with slow internet.

“As Sara, I did [3350 KM] to get rid of certain complex emotions and to feel closer to my father, who I’m away from, but also to get the film accepted into a festival so I can send him an invitation ticket and we can meet somewhere. We also need to use art to challenge the injustice of the world and to create alternative solutions.”

Sara was able to be reunited twice with her father in Lebanon following invitations from art institutions. For refugees like Sara, who hold French travel documents instead of passports, travel is a constant hurdle, and trips to Lebanon are nearly impossible without invitations from art institutions or organisations. Sharing this struggle and the joy of their reunion on Instagram, Sara wrote, ‘We live in the same world, but some are in prisons, whether it’s for the dreams stuck inside the country trying to escape, or the ones being outsiders and cut off from their family, or those stuck somewhere with no papers and rights. Yet through it all, we resist.’

While Sara’s work often explores themes of exile and her own experience as a refugee, she rejects being defined solely as such. “With what’s happening and the communication that’s taking place, I feel like as refugees, we’re always being put back in the same place. We’re always perceived in the image of the victim – the “refugee”, “the Syrian.” There’s always a specific label. The issue isn’t that I’m a refugee and I’m not ashamed of it, but what’s infuriating is the Western society’s use of this label.”

When ‘Towards A Light’ was exhibited at Tokyo de Palais, Sara was approached by a news channel for an interview. When asked about the motivation behind the project, she answered that she needed to do this project in order for her to love this part of her life. “I felt her enthusiasm immediately when I mentioned it,” Sara recounts the story. “She said, ‘Oh, so you love it now and you see this journey as something beautiful?’ and I answered, ‘No. I try to see it as something beautiful because I simply have no other choice, but nobody deserves to go through this dehumanising journey just to prove that they are worthy of living. It can’t be romanticised.”

Refugees everywhere often encounter incidents rooted in a saviour complex and misunderstandings, despite their continuous effort in integration.

“Is integration about completely erasing your identity or fully rejecting it?” Sara asks. “Refugees who struggle with the language are often looked down upon. Why? Integration shouldn’t be a one-sided effort,” Sara declares. “Where people who were forced to flee war put in immense effort without equal reciprocity. The complex bureaucracy is paralysing. We lack real rights, the right of freedom of choice, the right to resist.”

These challenges are just a glimpse into the broader struggles faced by Syrian refugees globally. While conducting this interview, a wave of anti-Syrian hate crimes erupted in Turkey, including physical assaults, property damage, and a mass leak of personal data threatening deportation. Just months ago, in April 2024, Lebanon witnessed another wave of hate crimes against Syrians, a recurring pattern in a region marked by tension and violence.

When asked about the recent hate crimes in Turkey, Sara referenced a video she saw online of a Syrian shop owner giving out sweets to Turkish people. She used the Arabic word “qaher” to describe her feelings when she saw the video. This term, untranslatable into English, encapsulates a complex blend of anger, frustration, and a deep, slow-burning sorrow. Sara then opened up about the emotions she felt in her early years of exile.

“When I first arrived in Europe, I lived with a deep sense of guilt for many years,” Sara admits. “First, because I had to flee my country and the huge sense of loss I felt for the people I left behind. There’s also this feeling of guilt towards the new communities because we came as refugees during a time of political crisis, and there’s this stigma attached to being a refugee. We felt like we constantly had to prove that we, too, are worthy of life.”

For much of her time in Paris, Sara felt trapped in a cycle of self-justification. “With the escalating violence, I’ve reached a breaking point,” she declares. “I refuse to apologise or feel guilty any longer. Those who have mistreated Syrians and other refugees have imposed this burden of proof upon us. It’s time for them to justify their expectations.”

Seeking to reclaim a sense of identity and belonging, Sara is committed to supporting the Syrian community. In 2024, she conducted a photography workshop for Syrian children in northern Lebanon. “I felt I could build bridges with people through photography or art. For me, this experience was more important than other experiences considered more prestigious”

Sara is also the founder of Al-Ayoun – Arabic for “The Eyes” – a photography collective uniting Syrian photographers and filmmakers through exhibitions and screenings. This initiative emerged from a personal longing. After embarking on documentary photography, Sara searched for a platform showcasing and connecting Syrian visual storytellers, only to find a few inactive platforms. She ended up establishing Al-Ayoun in 2021, driven by a desire for connection and a shared sense of identity.

“We do a lot of exhibitions and film screenings. Putting different projects and stories side by side creates a puzzle-like effect. I’m obsessed with this process. After completing this puzzle, we’ll figure out how to open doors for more photographers and communities.”

Sara has actively supported photographers in Syria, facilitating camera donations to those in need through fellow photographers in Syria. “I’m not an isolated artist,” she emphasises. “I create art to express these feelings, but I love sharing it and talking about it with people working on similar themes. I love using it as something that brings me closer to people. I love photography more than anything because it gives me an excuse to get close to people.”

“We, as Syrians, photographers, visual storytellers, and filmmakers need platforms like these. Syrian narratives are scattered in the diaspora and when we say ‘diaspora,’ it’s not only geographical distance. There’s an entire scattered community, even within Syria. Our stories, history, culture, language – we no longer share the same expressions and jokes. I have this longing, coming from a place of nostalgia towards something I never had, where I imagine all of us sitting together over a drink.”

Our conversation unearthed more questions than answers. Questions about our place in the world, our rights, and the systemic injustices we face. Lost in contemplation, I concluded the interview, ready to go home and bury myself in travel preparations for my trip to Syria the following day. “Don’t forget to say hi to Sweida for me,” Sara said with a warm smile.

Words: Sami Abd Elbaki

THIS FEATURE IS PUBLISHED IN ISSUE 03 OF ICON MENA PRINT MAGAZINE. ORDER YOUR COPY HERE.