News

Growing up in Syria meant learning to live under an omnipresent shadow of fear. One that lingered at the back of your mind until it became part of your very psyche. Trust was a foreign concept. “The walls have ears,” my family would whisper, just as most Syrian families did, passing down the saying like an heirloom. A warning never to utter a word that could be seen as criticism of the government. After all, anyone could be intelligence services, listening in. Fear wasn’t just an emotion. It was a system, a way of life. It wasn’t confined to the body. It seeped into the walls, settling into every crack and crevice, always listening, always waiting. In Syria, the walls were never silent, never the gentle, protective structures they were meant to be.

From an early age, Syrian children were indoctrinated to see the Assads as deities, and the eternal saviours of Arabism, unity, and bravery. In “nationalism” class, they were forced to memorise Assad’s speeches, and by the age of 15, joining the Ba’ath Party at school was mandatory. Refusing came with consequences. The regime instilled fear from childhood, weaving the Assad family into education and national pride, creating an emotional attachment that made disloyalty, or even questioning, feel like a betrayal of one’s identity and history. Over time, this enforced loyalty became deeply ingrained in Syria’s youth, forming what scholars call “consented loyalty”, where even as children grew older and recognised the abnormality of this glorification, fear kept them bound to it.

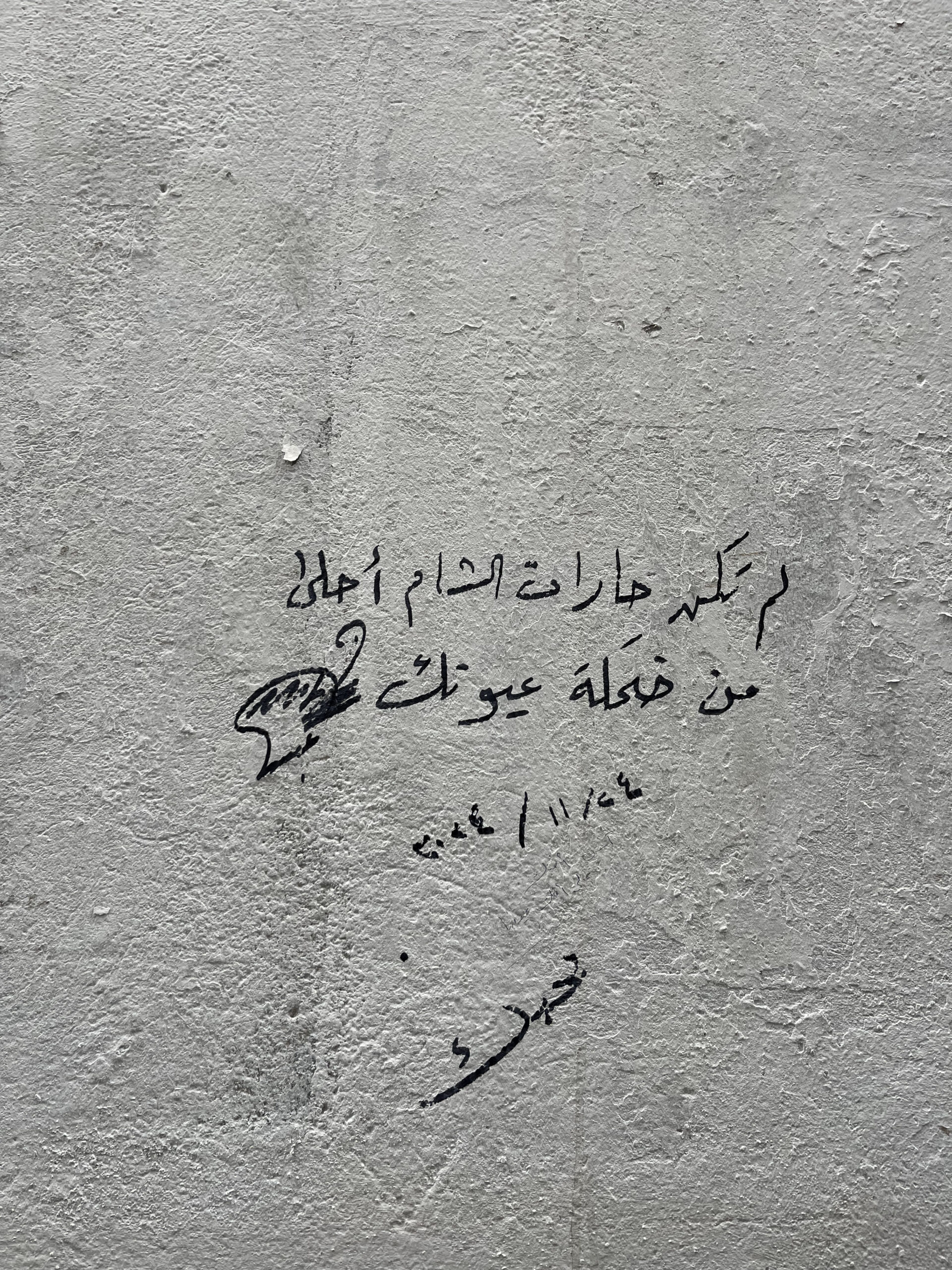

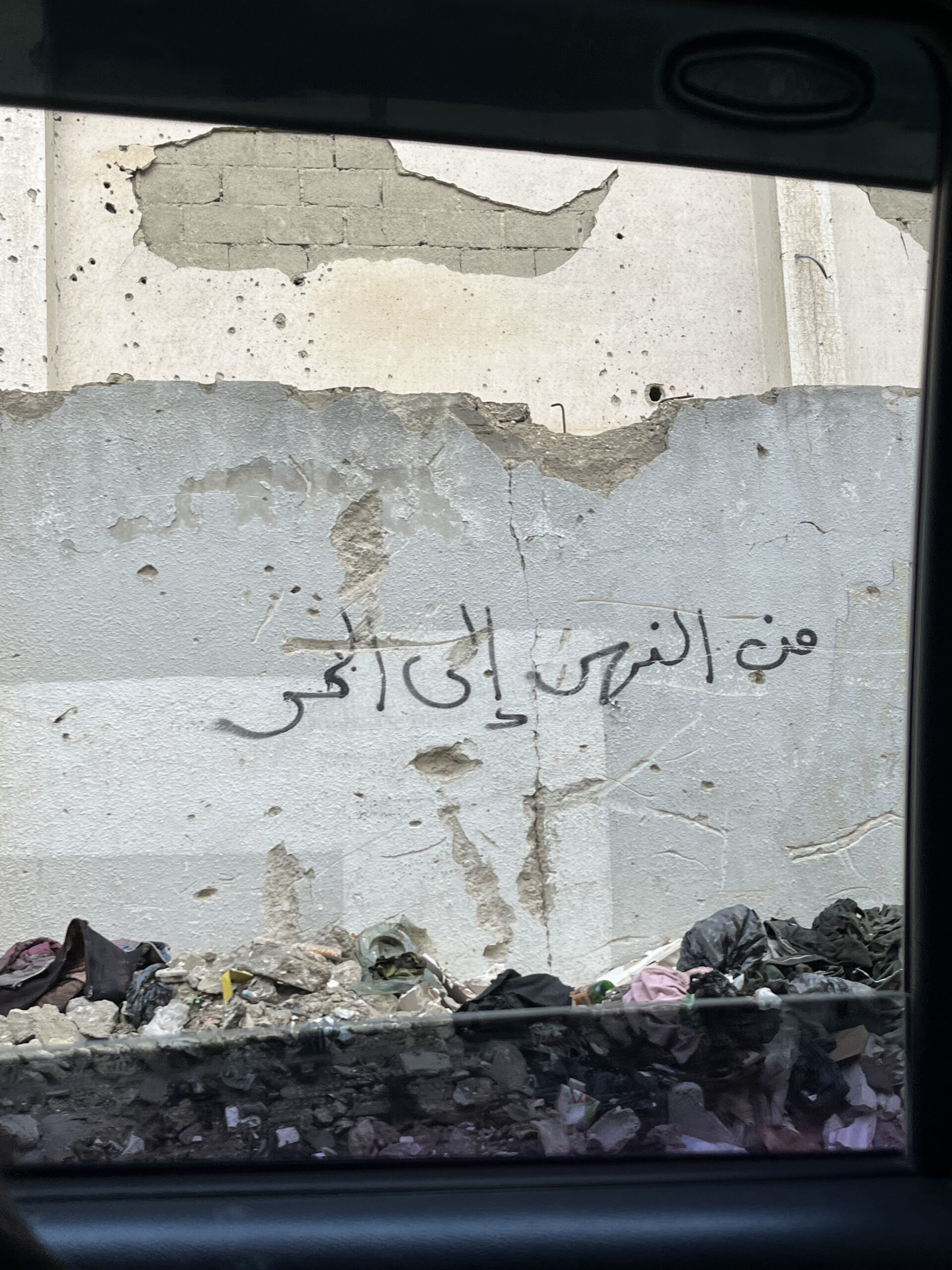

When the revolution erupted in 2011, it did not begin with weapons or mass protests. It started with a message scrawled on a school wall in Daraa by children inspired by the uprisings sweeping the Middle East. A group of boys, barely teenagers, dared to write: “Your turn is coming, doctor”, a taunt aimed at Bashar al-Assad, the ophthalmologist-turned-president. At the time, the region was ablaze with democratic uprisings, and now, at last, the wave had reached Syria.

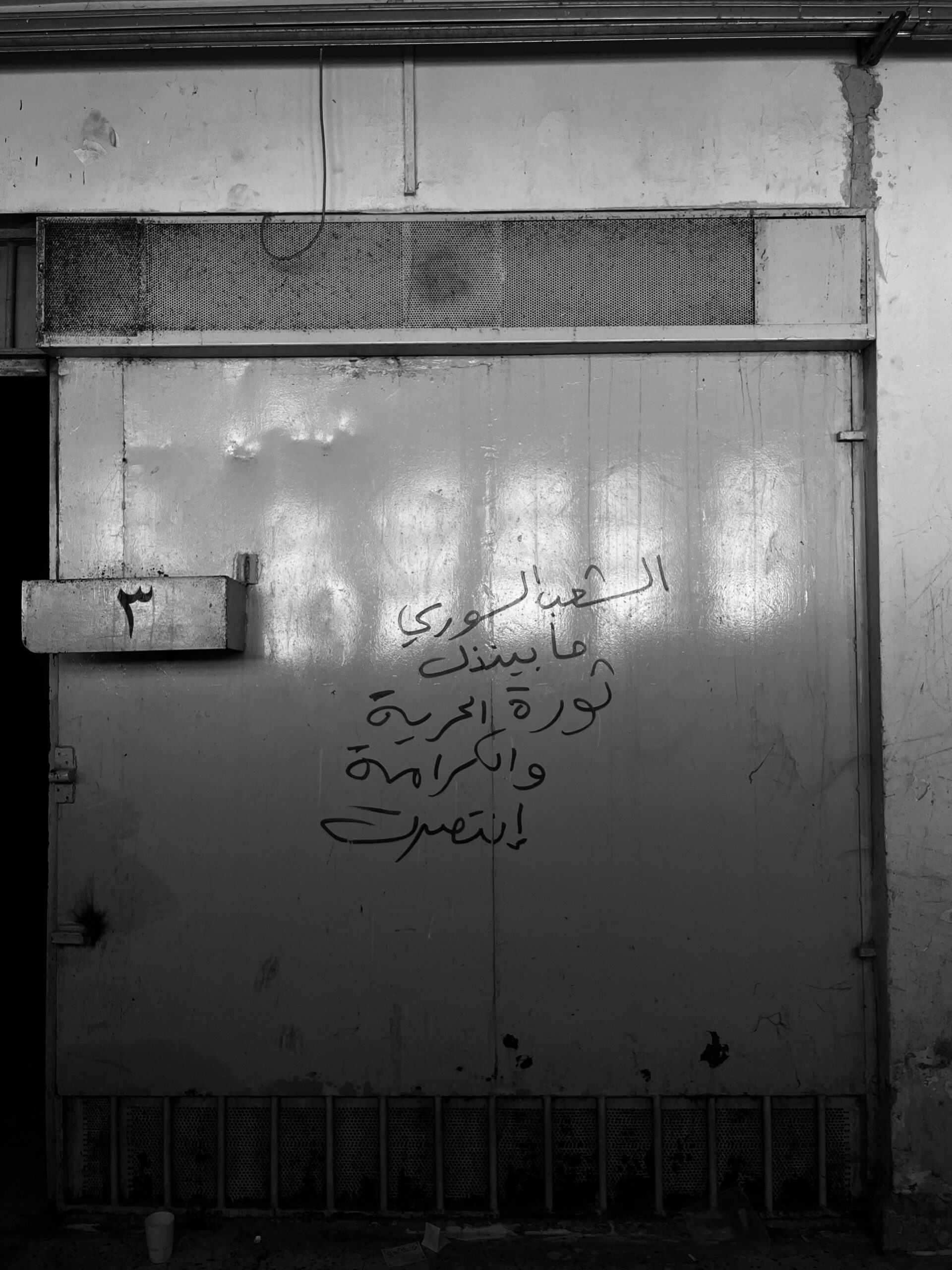

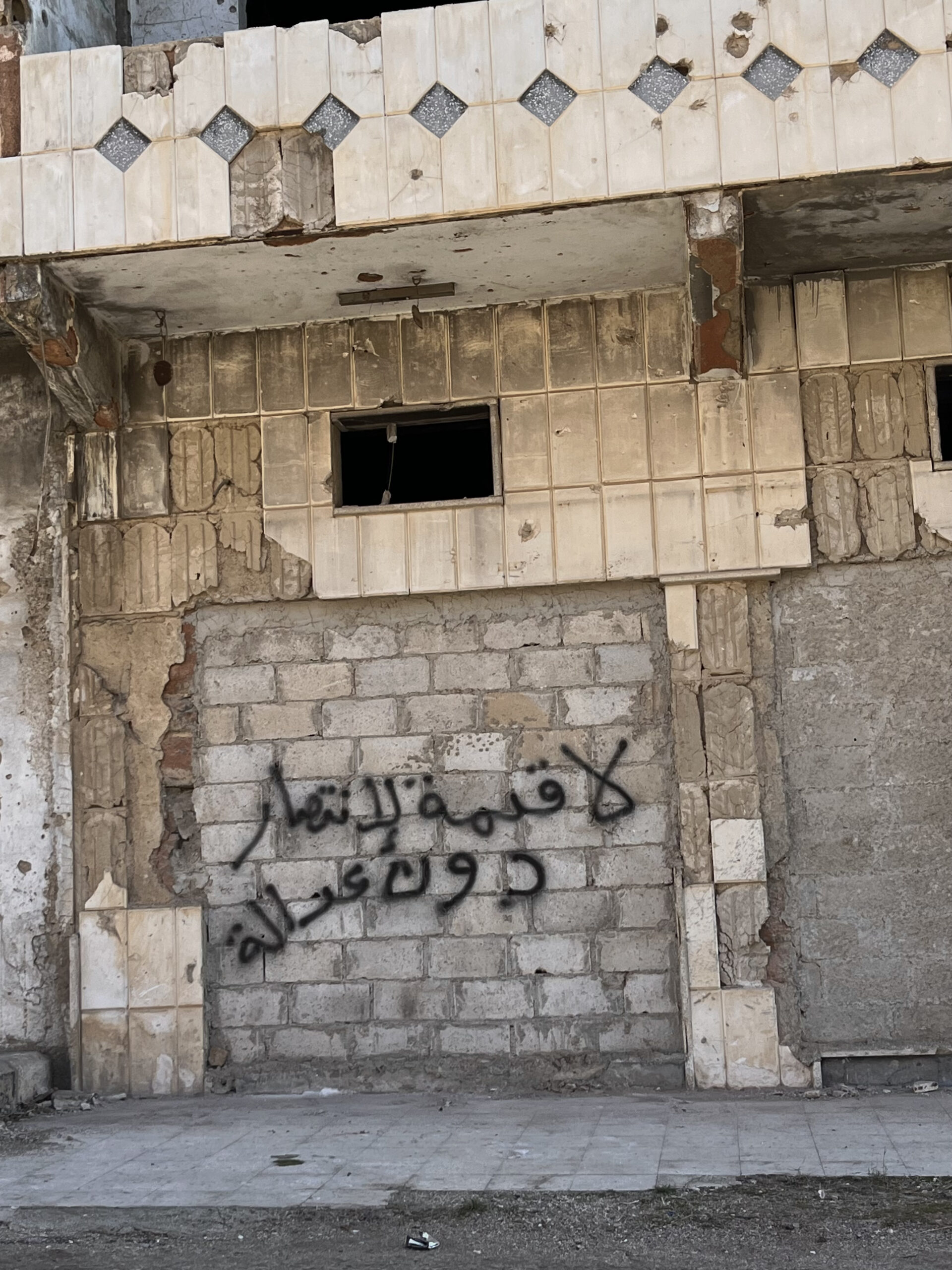

Graffiti became a form of resistance. Protest slogans spread across cities, and with each phrase painted onto a wall, fear lost a little more of its grip. Writing on the walls was no longer just an act of defiance, it was a declaration that Syrians were no longer afraid, or at the very least, that they were willing to fight despite their fear.

![]()

Kafranbel, a small town in Syria’s Idlib province, became one of the most powerful symbols of the revolution through its creative and striking protest banners. Beginning in 2011, activists in the town began painting large banners with messages in English, Arabic, and sometimes other languages, speaking directly to the outside world. Witty, poignant, and often laced with dark humour, these banners condemned the Assad regime, denounced Russian and Iranian intervention, and called out international inaction. Their sharp messages quickly gained global attention, appearing in protests, news reports, and across social media.

The idea of using banners in English came from a group of local activists, artists, and journalists determined to bypass Syria’s state-controlled media and speak directly to the world. One of the most prominent figures behind this movement was Raed Fares, a fearless activist and journalist who believed in the power of media to challenge tyranny, another Syrian, who would become a symbol of the revolution. Fares and his team at the Kafranbel Media Center began crafting banners every Friday, aligning them with the themes of the weekly protests sweeping across Syria.

Kafranbel’s banners became a tool to break through the Assad regime’s media censorship. With the state controlling all official narratives, these banners offered an alternative source of information, showing the world what was truly happening inside Syria. The activists hoped to garner international support, appealing to Western governments, the United Nations, and human rights organisations in the hope that their messages would spur action to protect Syrian civilians.

![]()

Beyond advocacy, the banners were an act of resistance. Many carried biting satire, mocking Assad, Putin, and Iran’s Supreme Leader, using humour as a weapon to strip the regime and its allies of their manufactured image of strength. Kafranbel also extended its solidarity to other struggles, from Palestine to Ukraine to Ferguson, recognising the interconnectedness of global movements for freedom.

The town’s activists ensured their messages resonated beyond politics, marking occasions like Valentine’s Day with banners that sent love to the world while pleading for solidarity against Assad’s brutal oppression. Some messages were bold and sarcastic, directly challenging the international community’s silence and exposing the hypocrisy of world powers as Syria burned before their eyes.

What made Kafranbel’s approach so unique was its fusion of art, humour, and direct messaging. Unlike traditional protests that relied on chants and speeches, these activists used visual storytelling to capture the world’s attention. Their signs were often simple yet powerful, featuring clear slogans and cartoons that needed no translation. Like graffiti in other uprisings, they became a voice for the voiceless, and a way to communicate Syria’s suffering and resilience to those who might otherwise remain detached from the conflict. Despite their peaceful approach of words being resistance, the town of Kafranbel paid a heavy price. Many of its activists, including Raed Fares, were assassinated by extremist groups in later years.

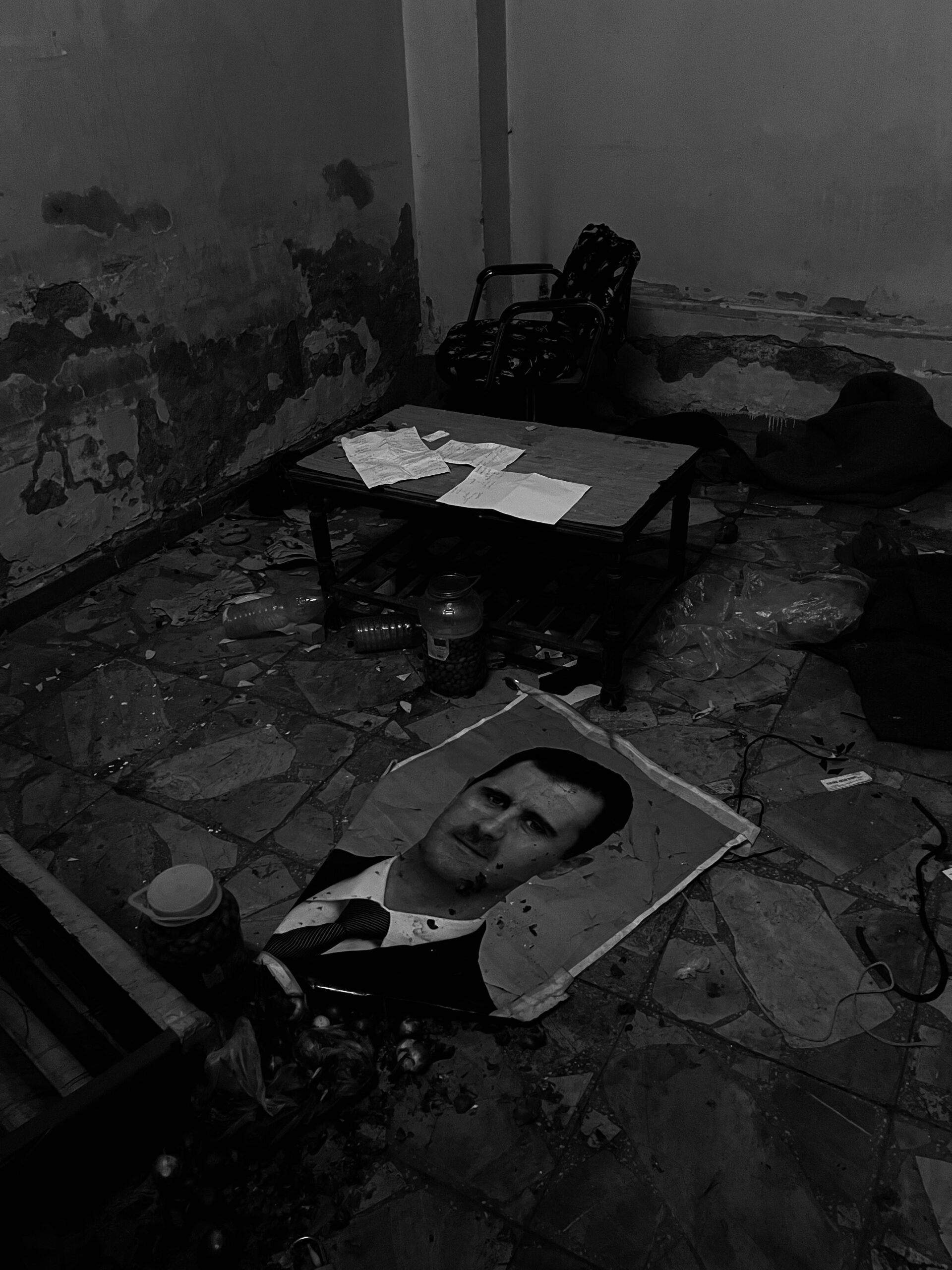

The other side of the walls carrying messages was the dark side of reality: the walls of Assad’s prison cells. The regime had built another Syria underground, even more monstrous than the one above. Anyone who dared to speak a word against the death machine was swallowed into this abyss. Young men and women who had marched peacefully in the streets would vanish, and their families left to understand, with silent dread, that they had been pulled into Assad’s black hole. That is what I call it: a black hole. In my belief, and in the belief of those who made it out alive by nothing short of a miracle, Assad’s dungeons were among the worst prisons in modern history.

![]()

On December 8th, 2024, I returned to Syria, just six days after the regime fell. It was my first time in 14 years. My family had been forced to flee because they had taken a stance on the right side of history, making a return impossible until now. I had not set foot in Syria since I was 11.

One of the places I had to visit, I could only do so by convincing myself that what I was about to witness was not real, that it was just a film playing on a screen. Because it was that unreal, like a set from the world’s most terrifying horror movie. But it was real. I was standing before the infamous Sednaya Prison and Branch 215, the detention centre. Two of the worst such facilities, where some of my friends had been imprisoned, and where my cousins had been tortured to death.

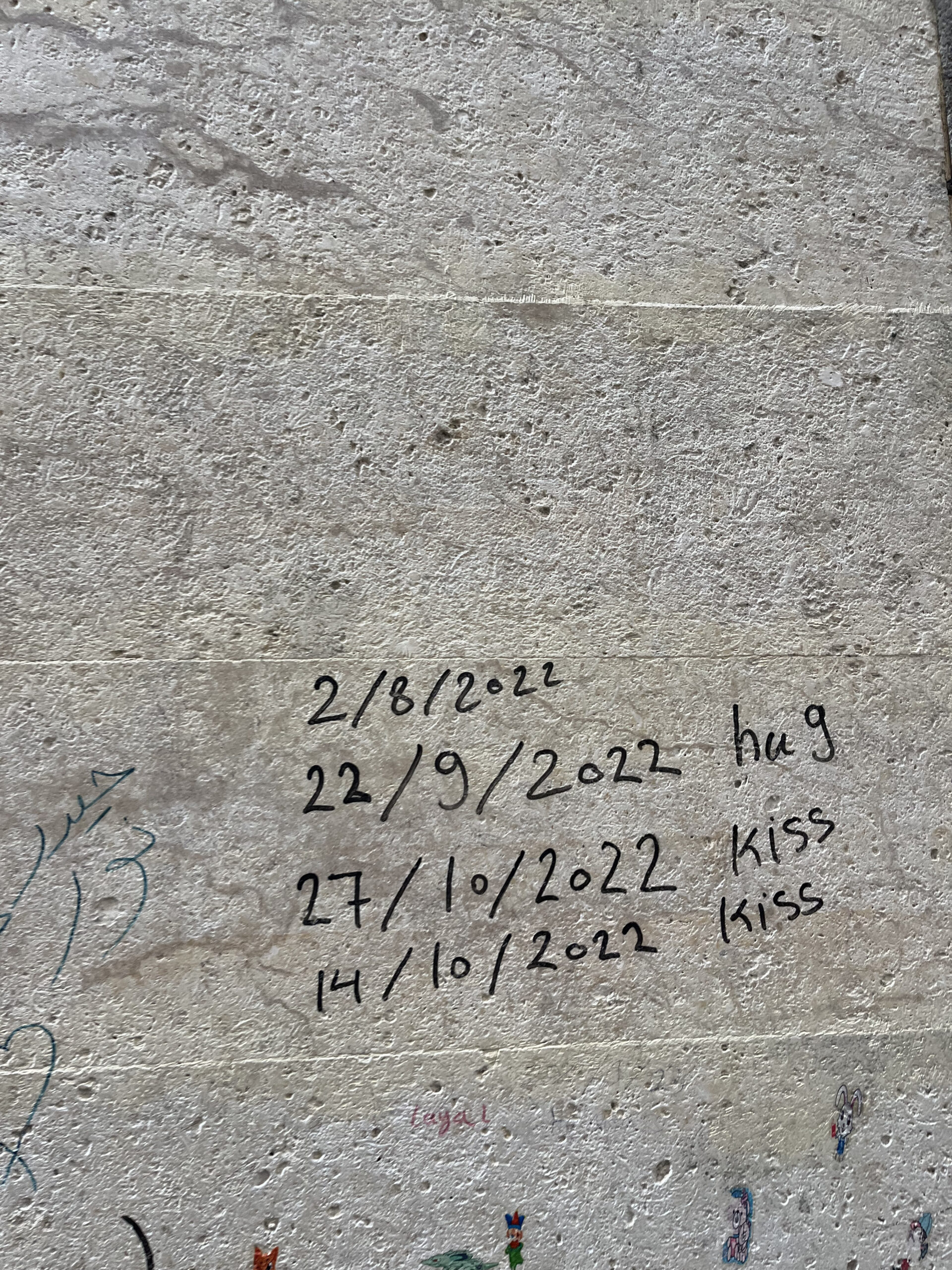

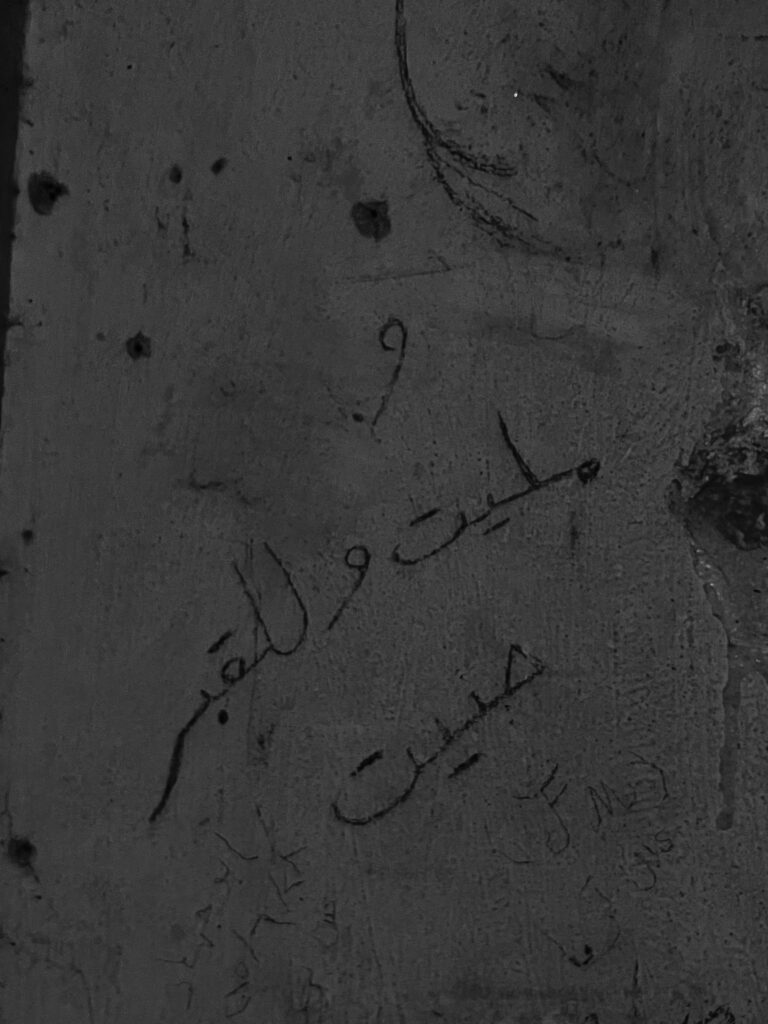

The walls of these prisons had been used as a way to communicate with the world. Not in real-time. Not even in the near future. Some messages were sent forward in time, meant for whoever might one day stand where I was standing. I still cannot believe that I had the most tragic of privileges to read, written on one of those walls: “I am bored and I yearn for the grave.”

Detainees, knowing they might never leave, carved their names, their dates, and their final messages into the walls. Some wrote to their mothers. Others to their children. Some tried to keep track of time, scratching tally marks into the cold stone, because in those chambers of torture, there was no knowing whether it was day or night. And then, there were those who used the walls as a canvas for their dreams.

Rehab Alawi was one of them. An engineering student, known among her cellmates for drawing bridges on the prison walls, bridges she had dreamt of building in a free Syria. She was one of the victims documented in the Caesar photos, among the tens of thousands of detainees who had been tortured to death. In the depths of captivity, where despair was meant to shatter the soul, detainees like Rehab left behind symbols of hope. The walls that confined her, the same walls that had absorbed the cries of thousands before her, became her canvas. With charcoal, a fragment of rock, even her own fingernails, she etched delicate bridges into the stone. In a place where the future had been stolen, where death lurked behind every locked door, the bridges she drew stood for something beyond those walls—the possibility of return, of connection, of a Syria that would one day emerge from the darkness, whole again.

Before Syria was freed, part of my work as an activist was taking the horrific Caesar photos across the world, to universities, parliaments, and foreign ministries, so the world could see the brutality of this regime. We would set up these photos, always with clear warnings about the extreme distress they could cause, as my colleague Omar Alshogre, a survivor of Assad’s prisons, walked people through the exhibit, explaining the hell he and his fellow inmates had endured.

It is beyond heartbreaking what happened to our people. We have a long road of healing and rebuilding ahead. But the cancer that was killing us is gone. And now, our pain can be alleviated by love, by care, by our passion and compassion for one another and for the country that endured the worst 14 years of its history.

Today, we stand on the other side of those walls of pain. We cross Rehab’s bridges. In this new Syria, the walls have become archives of our struggle. They bear witness to the whispers of fear and the screams of defiance. They remind us of the horrors inflicted upon us, but they also preserve our stories, our resistance, and our will to survive.

In Syria, the walls have always had ears. But now, they also have eyes.