News

It started with a particular type of face, one that you had seemingly seen hundreds of times. Perfectly smooth skin, high protruding cheekbones, almond-shaped eyes, a sculpted nose, and smooth pillowy lips. Ethnically ambiguous, but definitely female.

In 2019, writer Jia Tolentino coined the term “Instagram Face.” In her essay The Age of Instagram Face, published in The New Yorker, Tolentino took a long, hard look at the face that was taking over her feed, illuminated by a ring light and refined by IRL filler and virtual filters, “a single, cyborgian face.” It’s a face marked with a blank stare, optimised for engagement and loved by the algorithm.

It goes without saying that between endless hours of scrolling, selfie-taking, video-calling, and filter-testing, we’re confronted with our own faces more times a day than our ancestors probably did in a year. Our reflections are pixelated and constant. The digital screen has made the face an object of inspection, scrutiny, and more than ever, an optimisation project in real-time. On TikTok, the face often emerges as something to fix and manipulate, often assigned catchy adjectives and descriptors that morph into buzzwords. Take, for example, “cortisol face,” an extension of the “balancing your hormones” craze, which describes the effect of high stress on someone’s face from inflammation to breakouts and so on. Not an official diagnosis, but the TikTok gurus will definitely teach you a trick or two on how to depuff your face. A lot of the time, the advice will not include trying to alleviate the stress, causing your cortisol to spike, but that’s not the point. Time must not wear out your face if you are a woman. Don’t smile too wide, you’ll get wrinkles. Wrap and mummify your face before going to sleep to ensure you don’t strain your skin overnight. Get this pillow if you’re a side sleeper so that your face does not droop over time. And while these procedures and instructions are not as invasive as, say, cosmetic surgery, they’re not “unforeign” to anyone with an internet connection.

It would be very naïve to leave out the gender dimension from this discussion, but the rise of the misogyny-rife manosphere over the past couple of years, heralded most famously by social media personality Andrew Tate, has put a lot of pressure on impressionable young online men to optimise as well. Within these circles, there’s a growing obsession with “looksmaxxing,” an internet-born concept where men (mainly) try to enhance their physical appearance. At the heart of it is the belief that the male face is the key to status, success, and attraction. I took a quick dip into looksmax.org to investigate some of the hot face topics. “I (15 M) have always had a big amount of muscle… I realised that face is everything. My muscle didn’t get me girls nor did my money nor my height,” reads one of the posts on the forum. These young men will often post pictures of their faces and invite their peers to suggest things to be improved. Fix your hairstyle, clear your skin, define your jaw through facial exercises like chin tucking and get some jaw filler if you really need that extra push. The ideal male face is gaunt and chiselled, super alpha, expressionless but piercing.

The question of whether we were ever meant to see ourselves this often outside the confines of a mirror is settled: we weren’t. So is the conversation about what this hyper-visibility and the seemingly arbitrary associated beauty ideals do to wear and tear our sense of self. The self-love experts’ advice on the matter is almost always the same: stay mindful that what you see on the internet is not the reality, try not to compare yourself to others, or just put the phone down. I would argue that this neurotic fixation on the face has not only reinforced existing beauty ideals that glorify youth and conventional notions of masculinity and femininity, but rather created an entirely new one that isn’t rooted in any real-world sense of attractiveness. It’s harder to define, but its features are clear: a face that’s smooth, static, poreless, and stripped of expression and the markers of real life. However, beauty doomerism aside, this face has outgrown any one person, morphing into a perfect blur in the endless seas of AI-generated content.

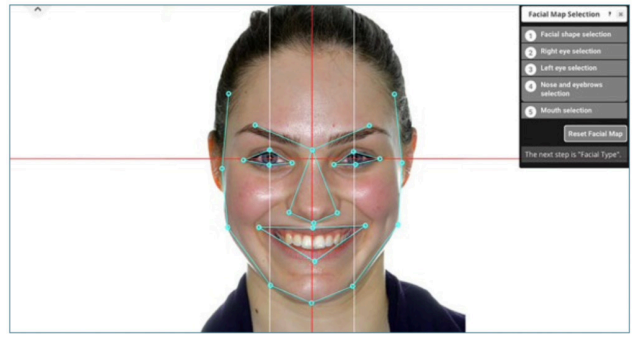

The panic over generative AI filters (specifically that one Bold Glamour filter on TikTok) on social media flared up so quickly in 2023 that a brand like Dove could make a buck by pitching in. These filters are not just overlays for your face, because AI filters often rely on a “generative adversarial network” (or GAN for short). In simple terms, this kind of AI works by comparing your face to a massive database of other faces, and based on that comparison, generates a new version of the input face. Smoother, more symmetrical, and so on. The output face, for all intents and purposes, is not your face with a filter on top, but a completely different one, stitched together to bear your resemblance. With the metaverse psychosis that took the world by storm for a hot minute two to three years ago, the conversation about human likeness in the virtual world was almost inescapable. The marketing associated with Meta-branded fantasy did a good job at selling that universe as a third space to exist virtually and front your human likeness there via an avatar of some sort, but these AI-generated faces are different. They’re not self-styled avatars, but real-time, machine-mediated outputs, virtual faces shaped by data. And as such, they tend toward the monolithic: one homogenised, idealised idea of a face built from a massive network of comparisons.

Websites like ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com and others like it present a compelling challenge to our understanding of facial realism and present a model in which we could make sense of this monolithic face. Using StyleGAN (a GAN variant), these platforms generate entirely synthetic faces, some indistinguishably human. To explain this phenomenon, researchers often turn to face-space theory, a theoretical cognitive psychology model which proposes a hypothetical multidimensional space in which faces are normally distributed along unspecified dimensions. In this framework, the most “average” features lie at the centre, making them more statistically common and easier for the human brain to process. Generative AI models, trained on massive datasets, tend to exaggerate this bias toward averageness. A 2023 study by Miller et al., titled AI Hyperrealism: Why AI Faces Are Perceived as More Real Than Human Ones, found that faces generated by StyleGAN2 were not only more average than real human faces, but also perceived as more attractive, familiar, and realistic, but notably less distinctive and memorable.

AI models and research evolve so quickly that the knowledge could be outdated by the time you finish reading a paper, and that’s not lost information on anyone. But the dilemma remains. I have an entire folder on my phone dedicated to TikToks of my favourite AI-generated ads (“favourite” used loosely). Most of them feature that same blank face that seems to creep up on the internet, or at least in the AI slop that does not present itself as such. Some are so poorly produced and are the result of advertisers cutting on budgets and hiring self-proclaimed prompt experts to produce their ad content, but others make you pause and look again. The line between fake and real gets so murky that I’ve had discussions at length with friends about whether the bizarre AI ads featuring Shakira and Kylie Jenner selling mobile games like Royal Kingdom and Travel Town (respectively) are actually real footage… which they are, to my surprise (and embarrassment). The uncanny realism is part of what makes them so eerie. Maybe it’s the flat tone of voice. Maybe it’s the eerily smooth video quality, the glassy, unmoving expressions, or just how cartoonishly off it all feels. It’s quite the layered scenario, an uncanny valley response to real moving images of the face.

So, where does all of this leave the face then, both as a cultural object and as an evolutionary medium of information storage and transmission, vis-à-vis all these factors pushing it towards a singularity? Long lines of research in neurobiology and genetics posit that, unlike most traits essential to survival, which tend to become more uniform over time due to natural selection, the face has evolved to become more distinct. Our facial variability is not a random accident but a feature promoted by evolution itself. This is because faces carry an extraordinary load of social and biological utility. They act as our most visible and expressive identifiers, helping us rapidly recognise individuals, convey complex emotions, or even make judgements about other individuals. Our faces are, in evolutionary terms, the most expressive anatomical canvas of any species on Earth. Early human ancestors lacked our level of facial dexterity, highlighting how much our capacity for facial expression through the facial muscles has evolved alongside our social complexity. The human face acts not just as a physical feature but as a storehouse of information, a transmitter of identity, emotional state, health, age, and intent. Our ability to pick up so much from a single glance shows just how deeply facial recognition is wired into human interaction and survival.

In his essay Peak Face, writer Carl Olsson traces the evolution of the face from its biological origins to its cultural symbolism and technological transformation, and looks towards a post-face future as a result. The human face, as we know it, didn’t always exist. It emerged through evolution as a response to the need for forward motion. Sensory organs clustered at the “front” and became a front-facing hub for perception, ingestion, and communication. The face’s previously described variability and social function came later, as the human face turned into one of the most information-rich parts of the body. Today, the face is the first thing we upload, filter, and present to the world in the digital realm. It’s the anchor of our avatars, the focus of algorithms, and the biometric key to our devices. And with the associated distortion through facial recognition software, deepfakes, AI filters, and other technology, we now interact with faces that are partly human and partly machine-generated almost every single day. Abstracted, optimised, emotionally hollow. We have reached the “peak” of the face’s utility.

The face, which was once a guarantee of a person’s presence and identity, can now be faked, swapped, or automated, leading to what the writer describes as an “inverse uncanny valley,” where the human face is processed and dissected without any real understanding of what it means. French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas saw the face-to-face encounter as the foundation of ethics, but in the context we’re looking at now, that transcendent power has been stripped away. The face, a signal to respond with care and humanity, no longer guarantees an encounter of vulnerability and humanity, ultimately undermining its authority as a vessel of truth.

Olsson’s line of thought teeters between speculation and provocation, but his central idea presents an interesting paradox: the more visible and hyper-present the face becomes through technologies like AI, the more it begins to vanish, dissolving into a sea of data and flattened into a kind of digital singularity with countless representational iterations. In this moment, a future where the human face becomes a vestigial feature still feels distant, but the idea isn’t far-fetched, and definitely deserving of scrutiny, despite the natural and social sciences not catching up.

Inspired by Olsson’s essay, artist Zein Majali created a short film titled The New New Face. The film was showcased at the 2025 edition of Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum, the fair’s flagship transdisciplinary summit, which was organised by commissioner Shumon Basar and curator duo Y7 (Hannah Cobb and Declan Colquitt). Running just under four minutes, The New New Face is a part-AI-generated, part-found-footage short film that opens with the image of an Anomalocaris, a shrimp-like marine arthropod from the Cambrian Period, over 500 million years ago. This was a time marked by the so-called “Cambrian Explosion,” when most major animal groups first appeared in the fossil record, many of which were the first to possess something resembling a face. In the sequence, the Anomalocaris quickly dissolves into a fleshy, pudgy human face resembling a failed slime-making experiment: the face of now.

From there, the film spirals into a surreal collage of grotesque AI-generated faces and internet-sourced videos, set against a deadpan voiceover that parodies the chaotic frenzied cadence of online self-optimisation culture. “I’m on day 22 of the 28-day face yoga challenge, and I’m thrilled with my progress,” it declares over footage of a TikToker obsessively massaging her cheeks. “If you’re not optimising, it’s a skill issue.” Later: “I’m not in it for the primordial obligation, I’m just looking to scale.” And finally: “I’ve never felt more seen.” It’s a chaotic but satirical montage that vaguely spirals through the timeline of the face through the hyperactive language of internet aesthetics.

“I didn’t have a take on the face. What can you say about Botox and filler and female beauty standards that hasn’t already been said?” Majali tells ICON MENA. “So I wanted to think beyond that and just [start with the fact that] we’re all morphing. What does that mean for the face? What does it mean when the face no longer does what it has done for years?”

The answer is the annihilation of the face, according to Majali and her film co-writer Laura Nicholson. Looking at the lineage of the face serves as a documentation of a self-optimisation to annihilation pipeline. Figuratively, but possibly literally. “I was having trouble imagining the end of the face, aesthetically, and I think one simple is that it looks like it is now,” she explains. I think an important facet of that notion is that the said annihilation does not necessarily mean the absence of, but rather the disabling of the face by undoing its progress: rendering it immobile, decreasing its variability, detaching it from an embodied experience, and so on.

Throughout its evolution, the face has seemingly found itself caught in a cultural feedback loop, a back-and-forth projection that started IRL and spilled into the virtual, or maybe the other way around. The face mimics the machine, and the machine mirrors it right back, ad infinitum. Somewhere in that loop lives the face explored throughout this essay. You could say the proliferation of the digital camera kicked this cycle off. Feeding our vanity and appetite for fun, the camera has captured our faces from every possible angle, whether we asked for it or not, and turned each one into the data used for the AI-generated weight loss app ads that you see on TikTok and Instagram. The screen doesn’t just literally turn into a mirror for you, but a projection of every captured face.

In her zine Hyper Ind3xical: Intermediality and Your Face, published by hyperhouse publishing, artist and writer Ruba Al-Sweel treats the camera as an omnipresent benevolent deity, a divine lens shaping how we see and are seen. She weaves together surveillance, AI, doxxing, networked human behaviour, and the idea of the face as “public domain,” blending internet aesthetics with Charles Peirce’s semiotic theory.

“In essence, the zine looks at the face as a product of co-option by the machine. So this avatar with the face is a complex nod, a complex network of meaning,” Al-Sweel tells ICON MENA. “In order for AI to generate a face of a girl, it has to study the pattern of every picture of a girl on the internet. So it’s really kind of the dwelling of embeddings in AI terms, but also in semiotic terms. The reason why AI is so masterful at making human-like faces is because there’s a massive database of faces out there that we have provided it with. There’s more cameras than faces in the world, and they’ve caught every angle of the face.”

“There are more than 5.3 billion internet users worldwide, and every single one of them has seen your face.”

By the time I finished this essay, Google had announced and released Veo 3, its most advanced AI video model yet, capable not just of hyper-realistic video visuals, but also of generating unprompted dialogue and immersive background effects to an impressive degree. The internet, of course, immediately put it to work trying to push its limits. My TikTok FYP is already in hysterics with users creating sentient AI characters begging to be taken out of the prompt they’re in. The faces it generates are eerily real, real enough to fool a Facebook Reels parent, but still carry the obvious vacancy. The emotion is not quite landing, and the faces are still lobotomised just enough, but the ability to recognise the fact requires sharper media literacy. It’s fitting that this should be one of the many final acts for the face as we’ve known it. “There are more than 5.3 billion internet users worldwide, and every single one of them has seen your face,” writes Al-Sweel in her zine. The machine learns us, wears us, and reimagines us in return. As AI slop floods the feed, the human face dissolves into a feedback loop of projections, everyone and no one, endlessly recycled. If the face doesn’t vanish, it might simply stop being ours, or we simply might not have the skills to recognise it anymore. I’m no doomer, but what comes next won’t be a return to the mirror, it will be something smoother, stranger, far less alive and, dare I say, sloppier. We’re part-way there.