News

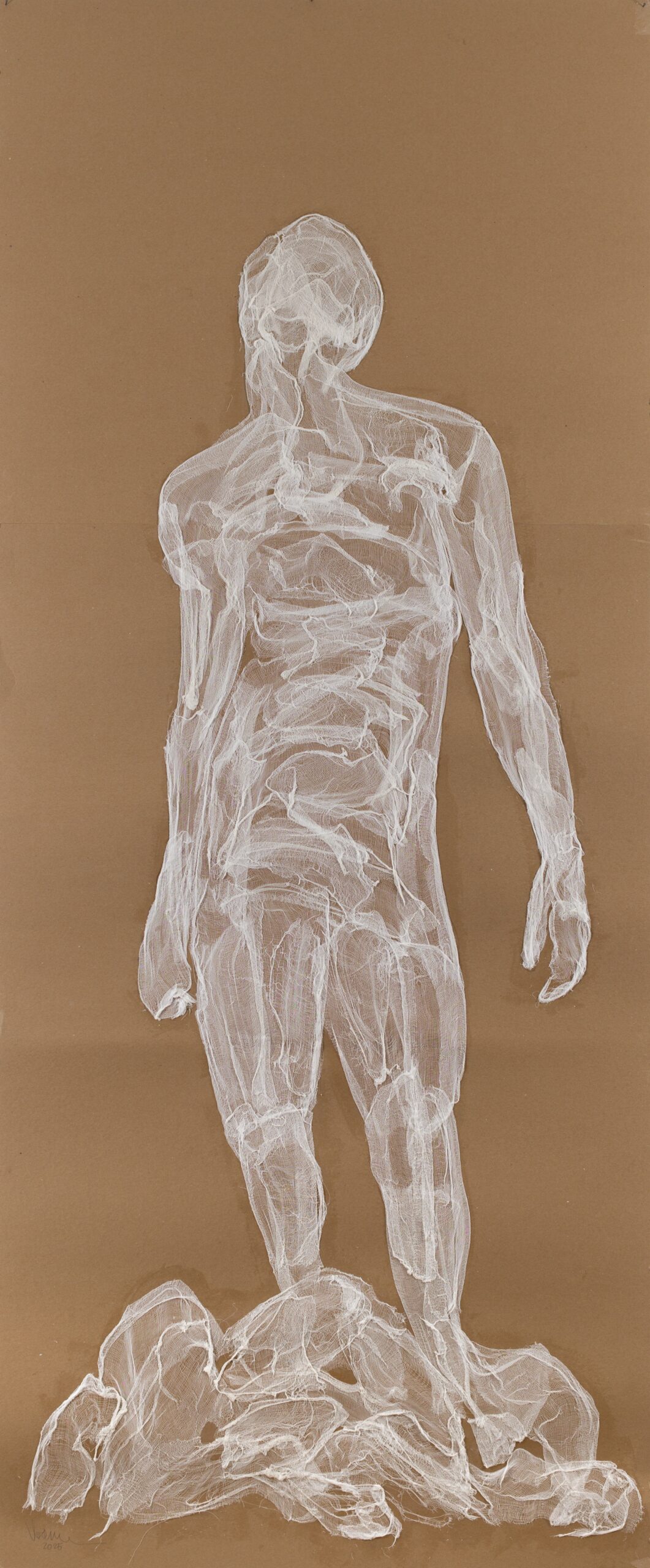

It is said that gauze, a light, open-weave fabric made predominantly of silk (or cotton) and used for surgical dressings and occasionally dress trimming, gets its name from Gaza. The city was a centre for weaving, exporting finely woven silk to the rest of the world from as early as the 13th century. And it’s not just linguistic synchronicity. Gauze is a material historically associated with healing, repair, and protection, becoming more than just a textile. It mirrors the very fabric of Gazan society: tightly bound and enduring, foreshadowing the continuity and resilience of the city despite its repeated turmoils.

Coincidentally, Hazem Harb’s grandfather worked a weaving loom, or nol, as Hazem told me in Arabic. His mother was also a seamstress who came from a long lineage of Gazan women weaving precious fabrics. Gauze, a material that Gaza-born artist Hazem Harb would use in one of his early performances, EXIT (2004), to bandage himself, later appeared in Burned Bodies (2008), a video installation created during his art studies at Città dell’Altra Economia Roma in Italy. Nearly 20 years later, he returned to it for his most recent solo exhibition, Gauze, at Tabari Artspace in Dubai.

For the Gazan artist, the need for healing is persistent and doesn’t seem to draw to a close. From his mother’s hand-sewn garments to his teenage years in Gaza that witnessed two Intifadas, to his departure for Italy at 20 years old, and now, living and settled in Dubai, gauze reappears time and time again, and if anything, the wish for a remedy appears to only tower, with his hometown completely razed.

“Imagine that Gaza, which had over 400 weaving workshops at its prime, and this is a confirmed number, just recently had a shortage of this material during the genocide,” Harb says. “It is emotional indeed, my use of gauze. An ode to a booming era. But there is also satire to it, if one may say.”

I am not sure if, when he left for Rome to receive his MFA at The European Institute of Design, he knew that gauze would not only materialise as a means to heal an existing and ever-growing wound of a fractured hometown, of witnessing a coastal city of magic and mending wane time and time again, but also as a way to bind feelings of exile, distance, and nostalgia. He jokingly calls himself an ‘Italiano Gazan’.

Having been far from his birthplace ever since the departure, Hazem Harb attempts time travel.

An avid collector and archivist, Harb curated Temporary Museum. For Palestine. in 2021, a solo exhibition showcasing his own rare collectables, maps, photographs, and artefacts, displayed in vitrine cases that captured a golden era of Palestine, with archival material dating as far back as 1779. Perhaps he was seeking a return through material, or a cure through imagined homecoming. While the exhibition is temporary, the chronicles are permanent. There is, after all, healing in time travel, in the act of resurrecting what has been erased

This enchantment with the remains of a prosperous past is a recurring motif in Harb’s practice. Though it is unclear how this obsession began, his mother may have played a role, seemingly an archivist in her own right.

“I remember as a child, I’d ask my mother to lay out our family’s photo albums for me, which I actually managed to salvage from Gaza. But you know, it was an odd thing to ask as a child, I’m talking 7 or 8 years old, instead of asking her for a football or a doll, for example,” Hazem recalls. Shortly after, he gets up to show me a small collection of his early sketches, carefully kept by his mother and later retrieved from Gaza. “Survived drawings,” he calls them.

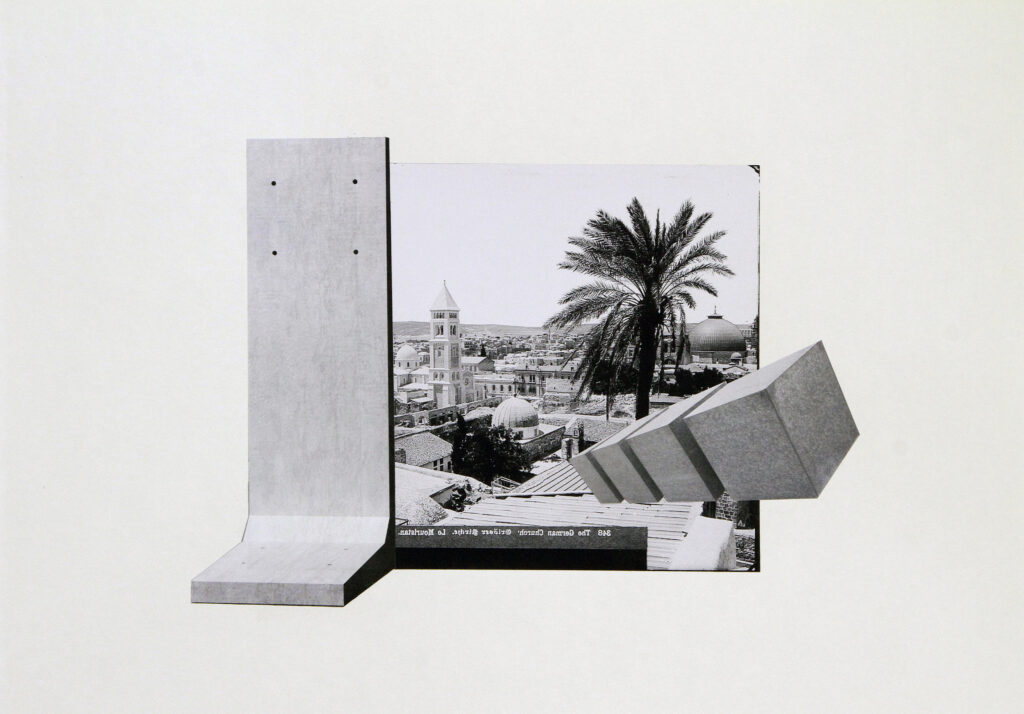

But he does more than preserve. He reimagines. Swinging seamlessly and poetically between a harsh reality and a burgeoning history, he employs collage as his medium. Archaeology of Occupation (2015) is a series of hefty collage pieces that layer pre-1948 photographs with floating, surreal concrete military structures. Dreamy yet distinctly architectural.

The architectural nature of these works suggests an alternate timeline, one where memory, space, and erasure collide. Time itself becomes elastic, stretching and contracting, neither fully present nor entirely absent, much like the diaspora experience. His use of linear forms, grids, and interwoven structures suggests a futurism rooted in modernist urban planning that acknowledges history while constructing new visual spaces.

If not an artist, Hazem Harb could have become an architect—a fact that becomes even more evident in his sculptural work. Before I could finish my sentence, Hazem cut me off, knowing exactly where I was going. He smirked, nodding in agreement, then, generous as ever, got up again to show me a folder he had started compiling just the day before, filled with his architectural sketches.

![]()

“I feel like, on the inside of me, I have an architect, maybe even an interior designer. So yes, definitely, architecture is always running through my head. That’s why I made Bauhaus as Imperialism,” he said, skimming through the sketches. “Perhaps it also goes back to the fact that I paint.”

While many focus solely on Hazem Harb as a painter, having practised drawing and painting since early childhood at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Gaza and building a long career of charcoal drawings and figurative work, his sculptural work is equally fascinating.

Whether stacking silver olive oil cans into the imagined cityscape of Liquid City (2021), arranging bars and crumbled fragments of Nabulsi soap in Soap (2021), or suspending rolled-up mattresses from the ceiling in I Can Imagine You Without Your Home (2012), Harb transforms the mundane into a meditation on forced migration and impermanence.

His sculptural compositions, fragile as gauze yet surprisingly strong, often recall the stark functionality of Brutalist architecture. Uncompromising and rigid, yet softened by cultural references that imbue them with humanity and gentleness. This tension between stiffness and softness speaks to the complexity of the Palestinian experience, shaped by both strength and vulnerability, wounds and remedy.

It’s not only the primitive and the found objects. Harb also incorporates glowing neon, often associated with urban modernity and commercialism, as a vehicle for time-bending, along with glazing mirrors. In his neon light text installations EXIST RESIST RETURN and I am the land and the land is you (both from 2021), he conveys age-old sentiments through a contemporary aesthetic. Another work, Between Earth and Heaven: Borders are Only in Our Minds II (2021), displayed during the Abu Dhabi Art Fair at Jebel Hafit Desert Park in Al Ain, takes the form of a mirrored 3D structure shaped to resemble the map of the Arab world, emphasising a romantic and idealistic hope for Arab unity. The reflective surfaces of these works invite viewer engagement, making them complicit in the narrative of shifting borders and self-perception.

Harb’s sculptural work brings his modernism to the forefront and further explains why his collage and archival work is so successful. His treatment of this material, though rooted in histories and commemorations, is fashionable and bright-coloured—almost reminiscent of a Piet Mondrian, but with a Palestinian background, both on canvas and in upbringing. It is a type of futurism inspired by the past but not bound by it; a distinctive marriage.

Like gauze itself, Harb’s practice is an urgent attempt to hold onto a multitude of fragments, to bind them together before they are lost forever.

Most recently, he took a notable step back, a shift from his usual practice after his home in Gaza, like many others, was demolished because of Israeli bombardment. “It’s a terrifying idea, losing your home,” he says. “I never really understood that concept before now, and I don’t think it’s easy to grasp unless one actually experiences it themselves. Your home, your memories, your childhood, your life… All that romantic and sentimental talk. It’s really terrifying losing it.”

The loss seems to have prompted a return to his early methods, moving away from installations and collage work and back to charcoal, once again travelling through a shared timeline, but also a personal one. Charcoal paintings of smeared faces, mushed and decapitated bodies, and an ash-like texture on paper. His most recent series, fittingly titled Dystopia Is Not A Noun, evokes an unsettling familiarity, eerily reminiscent of the imagery emerging from Gaza over the past two years. Disturbed and almost dystopian, it carries a sharp urgency, as if attempting to document a vanishing world before it disappears entirely.

“It’s a very urgent project, stemming from an urgent pain. For this exhibition, I had planned on displaying my archival material and collage work, but that was not what I was feeling at the time. It was not what the time demanded. I had to sit with my pain and transfer it to paper directly. The charcoal diminishes this distance from the work, it is my hand straight to the sheet.”

There is something undeniably medicinal about Hazem Harb’s practice—the metaphor of gauze, the time travel, the geometry, the clinical architecture.

As we bear witness to what can only be described as a Guernica in real time, Hazem Harb survives to narrate a personal story of being a Gazan artist living in exile, with family still inhabiting a flattened Gaza. Yet his approach is neither solely romantic nor defined by darkness or victimhood. He balances the shared with the personal without relying too heavily on either. Through his work, Harb performs a kind of ancient magic, a form of alchemy, transmuting grief into beauty without diminishing either.

His practice, perhaps, is a way of making sense of the world’s unravelling, and in return, mending what’s broken. His work is a reminder that while destruction may be immediate and overwhelming, the act of preserving, imagining, and reconstructing offers a defiant form of survival. It suggests that one day, gauze will no longer be needed, and Hazem Harb will return to his birthplace, and open the doors to the Gaza Contemporary Art Museum, his life-long dream, overlooking the sea.

WORDS: Salma Mousa