News

What did we have before the television? What could we focus on? What did we dream within?

For Hussein Shikha, the answer is simple: the carpet. Growing up in Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq War, the Gulf War, and the American invasion, frequent blackouts interrupted his childhood and stripped away modern forms of escape. In their absence, he turned to the intricate patterns of Southern Iraqi carpets, projecting imagined video game worlds onto their designs.

Today, Shikha is an artist and researcher working across textiles, video games, film, and animation. His practice reanimates fragmented histories—personal, political, mythological—through repetition, variation, and non-linear forms inspired by thinkers like Ibn Arabi, creating spaces for reflection, remembrance, and spiritual resonance.

When did you decide you wanted to become an artist?

I don’t think becoming an artist was ever a conscious decision. It felt more like something shaped by circumstance. When I arrived in Belgium as a young refugee, I was pushed towards educational programmes meant to lead to quick employment: cook, woodworker, whatever was available. I barely knew the Dutch words for basic tools. Eventually, I landed in a programme called Publicity, focused on advertising. That’s where I was introduced to software like Illustrator and InDesign. I realised I could communicate visually, even as I struggled with language. That was a turning point. One of my teachers there really believed in me. She encouraged me to apply to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, something I wouldn’t have considered on my own. Without her, I might not have pursued art.

Where did you grow up? When did you leave?

I grew up in Baghdad, born in 1995, right in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War. Iraq was already in a difficult state, and then came the American invasion that strategically resulted in heightened hostilities between the Sunnis and Shia in Iraq that fuelled hate and aggression, that resulted in the civil war. It was a challenging experience. It was a period of heavy instability, violence, and fear. My family is Shia, and we lived in a predominantly Sunni neighbourhood during a time when sectarian tensions were being actively fuelled and manipulated, especially by foreign powers playing ‘divide and conquer’ in the region. That tension shaped our daily lives. We were under constant surveillance. There were death threats painted on our walls. Things got too dangerous. We had to move around. First to Basra, then Nasriyah, then Syria. I think in total we moved 10 times. That instability definitely shaped how I see the world today, how I process systems of power, fear, and belonging. Eventually, in 2009, after years of moving, my father was finally able to bring us to Belgium through family reunification. That’s when I left Iraq.

Where did you study art? What was it like learning there?

I got both my BFA and MFA at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. [The curriculum] was all about the Western canon. Greek statues, Roman temples, the usual suspects. Maybe a slide or two on Egypt. I don’t think Mesopotamia was even mentioned. There was no real interest in global shifts, or how Islamic art, Arab history, and other regions contributed to what we now call “Western” art. It all felt very narrow and selective. After finishing my BFA and MFA, I felt pretty lost. I had this sense that the work was being misunderstood or dismissed, and I needed a space where it could be taken seriously, where I could understand why it mattered, not just intuitively but intellectually and politically.

That shift happened when I joined the Advanced Master of Research in Art and Design, a postgraduate programme. It was the first time I was surrounded by people who actually understood what I was doing and who helped me understand it better too. Through this programme, I was introduced to thinkers like Édouard Glissant, especially his concept of the right to opacity, the idea that not everything has to be fully explained or decoded to be valid. I also engaged with José Esteban Muñoz’s writing on disidentification, and how people build identity through friction, through refusal, through surviving oppressive systems.

When did you begin to make connections between your upbringing and your practice?

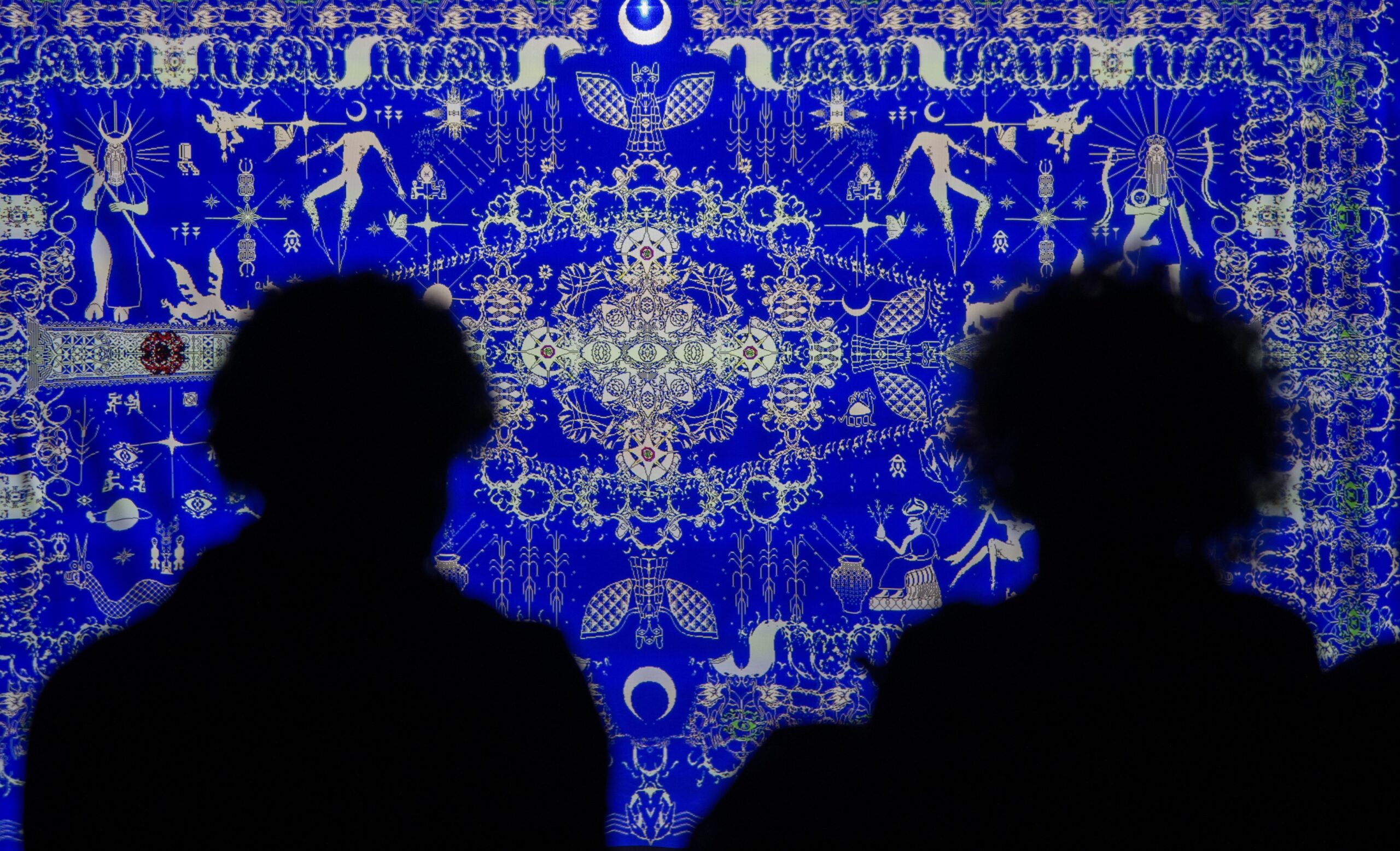

It formed gradually, but it really crystallised during my MFA. I was seeing other students doing deeply personal work, someone was researching their ADHD, another was working on a project about eczema. And it made me think: what’s something that’s always been around me? What shaped me, visually, emotionally, culturally? That’s when I started reflecting on the visual environment I grew up in. Our house in Iraq was overflowing with ornamentation. My mum had all these patterned tapestries and carpets, some gifted to her, some passed down from my grandmother, who worked with yarn for weaving. Even the couches had covers, and those covers had their own patterns. The walls had tapestries too, like one of Imam Ali holding his sword with a lion beside him. Fatima’s hand was everywhere. You couldn’t escape it. It was the visual atmosphere I was submerged in.

As a kid, we weren’t allowed to play outside much because it was too dangerous, so my parents got us a video game console. I was the only one really into it. I remember playing Legend of Mana, and the game’s aesthetic—lush, ornate, kind of pixelated—reminiscent of the carpets around me. I would be in the middle of playing, and the power would go out because electricity cuts were constant in Iraq. The TV would go black, and my gaze would just naturally drift to the carpet. And somehow, I’d continue the game there, in my head, tracing the patterns, escaping again. That overlap stuck with me. The visual logic of a video game and the carpet felt connected, both grid-based, both pixel-like. Later, I learned about the Jacquard loom and how it was a precursor to modern computing. I realised that textile logic, especially in places like Iraq, isn’t just decorative. It’s computational, algorithmic. It’s a form of coding. Still, the dominant story of computing tends to erase or ignore non-Western contributions, presenting it as an exclusively Western achievement.

What helped you get to where you are now? What did you learn?

A big part of it is thanks to my mum. She was supportive of me pursuing art, which, honestly, I didn’t expect. But she encouraged me anyway. And I really value that. I think that’s something I’ve really held onto: the need for my work to be legible, not in a simplistic way, but in a way that doesn’t alienate people who didn’t grow up in elite art institutions. I see so much contemporary art that feels designed to exclude people like my mother, and I find that unsettling. Who are you speaking to? What are you upholding? What do you want people to experience from your practice?

I remember reading Laura Marks’s essay, where she talks about how people experience carpets physically and emotionally, Thinking Like a Carpet: Embodied Perception and Individuation in Algorithmic Media. Marks suggests that carpets, particularly abstract ones, bypass our habitual cognitive expectations, directly engaging our nervous system, how carpets invite this meditative, empathetic state. But yes, if I had to put it simply: empathy. A moment of reading, of pausing, of connecting, where it requires the spectators to view with modesty and patience. A carpet’s visual language can do this.

What are your favourite examples of video games appearing in visual art?

One game that really stuck with me is Final Fantasy XIII. The way it weaves mythological and divine narratives into a futuristic world deeply resonated with me. The main character’s sister is being purged, exiled by the government, for coming into contact with something they’re not supposed to. Basically, being marked as dangerous just for existing differently. That storyline felt personal. As someone who migrated, the idea of crossing borders, being made into the “other,” and resisting forced roles really hit home.

How is your archival engagement with Southern Iraqi carpet design?

I don’t see myself as an archivist in the traditional sense. I’m not interested in just collecting, categorising, or preserving symbols as static objects. But also, my engagement is about reanimating rather than only documenting. I try to return to these symbols not to fix their meaning, but to let them breathe again. For me, preservation is less about freezing something in time and more about re-remembering, through fabric, through pixels, through stories that haven’t been fully allowed to surface. At one point, I did think I had to collect every symbol, trace its meaning, build some exhaustive taxonomy of motifs. But during my time in the Advanced Master programme, I began to see how violent that approach can be. Why should we insist on giving one fixed meaning to something, especially when we’re separated from its original context by geography, time, and history? Symbols hold multiple meanings. I try to engage with these symbols not as codes to crack, but as living fragments that can be reassembled, reimagined, and felt. So in that sense, my carpets themselves are archives.

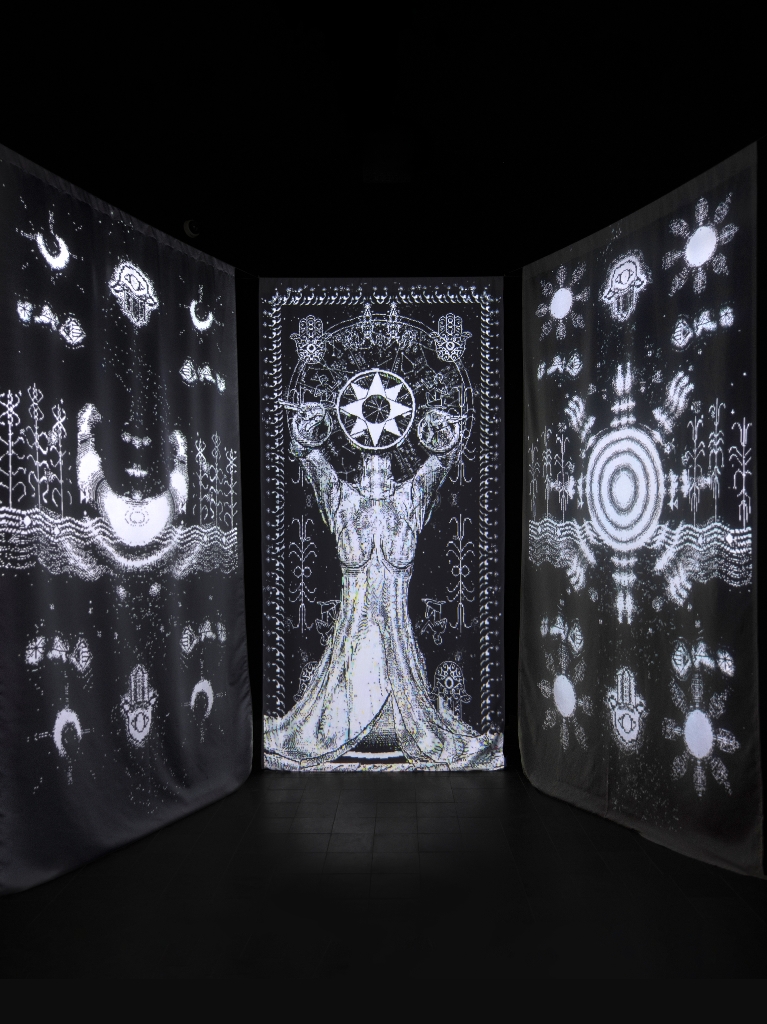

The video game I’m developing is an archive. It’s the third step in a larger process: first I design pixel-based motifs and symbols, which are woven as Jacquard tapestries (Garden of Eden); then I animate them as moving carpets through projection or LED matrix (Digital Carpets); and finally, I code them into a pixel-based video game, Legend of Sumeria, turning everything into an interactive, playable archive. The animations and installations I make, they all function as ways of holding and transmitting cultural memory. They don’t claim authority. They invite conversation. They create space for stories that were never allowed to be fully told, and eventually transformed, especially in the context I grew up and inhabit. My role is to hold these fragments with care, not to resolve them, but to give them room to keep evolving.

How does it feel to create work meant to be touched? Do you prefer audience interaction, or would you rather they engage with a distanced scrutiny?

I don’t mind if people touch the work. In fact, I think it’s important. These are tactile objects. When you get close, you see the density, the layers of threads, the detail. These works hold stories that deserve to be felt and not just looked at from a distance. Of course, they’re fragile. They’re expensive to produce. So I do want them to be interacted with respectfully. But I’m not interested in forcing people to stand at a polite distance, squinting with academic detachment. There’s also a political layer here. Many Southern Iraqi carpets, especially those made by the Marsh Arabs, are now locked away in museums or private collections. There’s a woman in Switzerland who owns a few and won’t let anyone touch them. That dynamic is hard to ignore: someone far removed from the culture claiming the right to preserve these objects while denying others access.

For Huriya, Huriya, Huriya, Huriya (2024), what was the experience like to be commissioned for a publicly facing work about Palestine? What discussions did you have about the proper ways to engage the public with an inherently diplomatic or identitarian symbol: the flag?

First, I want to clarify that the flag wasn’t originally commissioned to be about Palestine; that was my decision. When the project began, I had a completely different idea in mind. The process started before 7 October. But after that, I felt very strongly that if I had the chance to show something this large, this visible, in public space, it had to be about Palestine. It was something that had been on my mind, on many of our minds, for a long time. And seeing others stay silent, especially artists and institutions with public platforms, made the choice even clearer. To have access to a massive public gesture and not say anything felt like complicity. That silence was deafening.

The flag was huge—about nine metres tall and several metres wide—and to me, it felt only natural that it would carry a message about Palestine. At the time, most institutions in Belgium were still silent or speaking in vague, depoliticised terms, this kind of “all lives matter” discourse that completely erased what was actually happening. So in a way, the flag became a counter-narrative. A refusal to be neutral. And since then, I’ve noticed more and more institutions in Belgium publicly stating their support for Palestine, which is a good shift.

When you dress a gallery with your work, how do you wish it to transform our relationship with space and our own presence in a gallery?

If we’re talking about what I wish for, then I wish for the gallery space to be transformed into something that’s not just about looking, but about being. Two years ago, I organised a festival Here and Then, Now and There, where I tried exactly that. The main exhibition space wasn’t just for showcasing artwork. It had carpets on the floor where people could sit, talk, gossip, and rest. There was a console where you could play video games—including the one I had made—but also retro games from a bootleg emulator I set up. What was beautiful was seeing all these different kinds of interaction: kids playing games, aunties chatting, others reading essays I had printed out and placed in a reading corner. It was alive. And it made so much sense to me, because that kind of space reflects the way I grew up, where carpets weren’t just decoration but gathering points, where storytelling happened, where people existed together. It felt like a family gathering at Grandma’s. That’s what I’d like to see more of in galleries. But I also understand that many galleries aren’t ready for that. These kinds of settings attract people who don’t usually feel welcome in those spaces, and some institutions are not comfortable with that.

![]()

What discussions have you had with yourself and within your practice around preservation through diaspora?

For me, the carpet became a metaphor. It helped me make sense of my own displacement and how I’ve been read, or misread, through various systems: as a refugee, as Arab, as Muslim. The carpet, like me, carries meaning that’s been lost, erased, or deliberately mistranslated. We can’t “read” these textiles the way people once did, because that knowledge has been fractured or denied to us. When we first arrived in Belgium, I wanted nothing to do with Iraq, with being Arab or Muslim. I tried to push it away. But over time, I’ve realised that was never really a personal choice. My work now is an attempt to refuse that erasure. I want to develop a hybrid visual language that doesn’t just represent identity but expresses it, in all its contradictions, diasporic ruptures, and evolving forms. Especially now, when it feels like people are becoming less and less interested in these histories, mythologies, and ancestral knowledges—we’re drowning in spectacle. And to me, that’s exactly why it’s urgent to make work that reclaims and reanimates what’s been pushed to the margins.