News

Artists, magicians, stage designers, cinematographers, people who live by the maxim that the hand is quicker than the eye, are aware of the imperfections that optical vision alone carries, especially in the subjective phenomenon of perception. Philosophers like Alva Noë and Kevin O’Regan have described this as The Grand Illusion: the possibility that our conscious experience, the way the world appears to us, is not a faithful window into reality, but itself a constructed fiction. Not only could the external world deceive us, but our very sense of perceiving it may be prone to elaborate misrepresentations. In an image economy built on shock and spectacle, this illusion is exaggerated. The senses are constantly pulled in opposing directions. Seduced, saturated, then left scrambling for coherence, wondering what we just saw. It triggers a memorable quote from my first lecture in Neuroscience as a university student: “The eye does not see, the brain sees.”

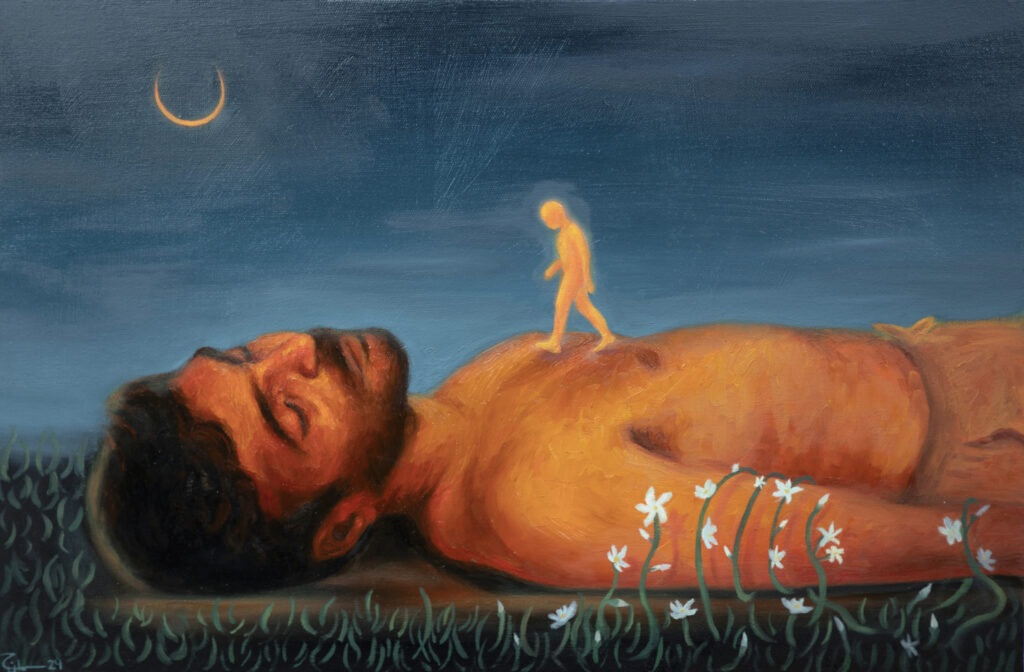

This is where Jude Samman’s work dwells. At just 24, the Jordanian painter of Syrian descent, now based in Amman, creates oil paintings that feel like counter-rituals in a visual world obsessed with clarity. Her work doesn’t seek to explain or be decoded. It invites slowness. Her subjects do not gaze outwards for approval; their eyes are often closed, or turned inward, as if in conversation with something ancestral, sacred, waiting after years, to be called upon.

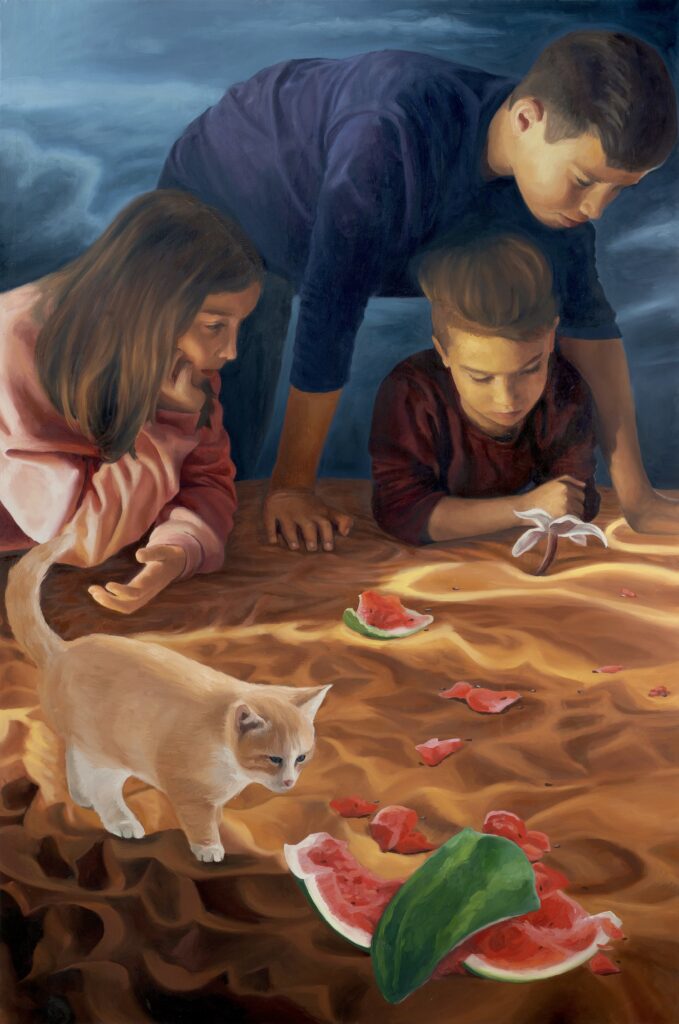

Working primarily in oil, Samman creates landscapes where perception is gently, almost romantically, distorted, and reality drifts into a hushed dream-state. Her paintings feel like whispers. Not necessarily whispers from some distant elsewhere or a place I’ve never been, but from somewhere deeply familiar, like echoes of a forgotten emotional language. At times, I wonder if they speak not to another dimension, but to the interior terrain of my own childhood, an imagination shaped by a busy life in London and busier summers in Syria, all within the embrace of an Iraqi family. The most resonant kind of whimsy doesn’t just reimagine the world, it reclaims the imagination we were once fluent in, before it was surrendered to the more rigid architectures of adult thought. In this way, looking at Samman’s work doesn’t feel like an escape from reality at all. It’s registered as a soft return to the instinctive rhythm of my tender, lucid imagination as a child.

In the time of algorithmic modernity, where technology fuels both unprecedented creativity and an eerie sameness across design and the arts, the boundaries of what is considered ‘progressive’ can start to feel curiously stale. Whimsical work offers an antidote to that. Especially when it engages nostalgia not as adult mourning or aestheticised longing, but as a return to the imaginative clarity of childhood. This kind of nostalgia doesn’t replicate the past, it ruptures the script. It reawakens the emotional centres we once inhabited freely: the playgrounds, real and imagined, that shaped our earliest ways of seeing and dreaming.

Samman’s paintings have an atmospheric, suspended quality to them. Time blends and melts into the moments she immortalises. Familiar actions like gardening, sleeping, or quiet conversation are recast in sensorial dreamscapes that feel both deeply welcoming and gently estranged from reality. They resemble what one might call friendly hallucinations, visions that alter perception, not to unsettle, but to soothe. Her subjects appear to exist in a soft limbo between the real and the imagined, evoking comfort without ever becoming entirely knowable.

This is intentional. “I bring together familiar objects in unfamiliar ways,” Samman tells me, “hoping the viewer recognises them while also questioning the context they’re in.” She invites her audience to step into that liminal space, where meaning rearranges and perception becomes fluid. “It’s a way of sharing how I see. When something ordinary shifts in meaning for me, I want to pass that shift along, to invite the viewer into that quiet, uncertain space where perception begins to stretch.”

It feels that hope, grief and daydream coalesce to form a deeply felt political narrative in these paintings too. This feeling peaks behind the curtain of the formalities of how we are meant to feel, going beyond sterile and often academic and rigid conversations about geopolitics and coordinated ‘solutions’ that seem to solve nothing. The work confronts head-on the bewilderment of living in a fractured reality, one that rewards the agitators and thieves while stereotyping the voiceless and oppressed. “Even when I speak softly, the politics are there, woven into symbols. I don’t always say it directly, but I leave space for the audience to feel it, to make the connections,” she explains. Samman isn’t interested in filling in gaps, but in opening them wider, to contemplate what could be from what is.

Samman’s artful incorporation of Middle Eastern traditional icons never falls into cliché. While cultural symbols sometimes face criticism for oversimplifying complex identities, it’s important to recognise that much of the iconography found in SWANA literature and imagery is vibrant and living. Beyond mere keepsakes or dormant relics, our relationship with fruits in art embodies the memory of our deepest sanctuaries, such as our mothers’ homes, adorned with the jewels of the natural world. The same is true for many cultures globally. An essay titled “In Defence of the Mango Diaspora” challenges the dismissal of mango imagery in South Asian diaspora writing as a tired cliché. Rather than a reductive stereotype, the mango symbolises lived and salient memory, affirming the complexity of diasporic storytelling.

Though such motifs can risk veering into self-orientalism, Samman engages them with nuance and intentionality, reanimating rather than reducing them. Our bond with the soil is symbiotic, and charms us to value its reference wherever we may see or feel it.

“The pomegranate, a fruit of paradise in Islamic tradition, symbolises fertility, abundance, and spiritual renewal,” Samman explains. “In Sands of Resurrection, I painted two Arab women, one veiled, one not, to challenge the notion that there is only one way to be an Arab woman. Both exist, and can exist side by side. In this piece, the pomegranate becomes a divine feminine force, its emergence from the desert soil marks the start of a transformative journey toward freedom.”

Visuality, especially within colonial and patriarchal frameworks, has long sought to dictate who Arab women are permitted to be. Samman’s paintings gently unravel this legacy. As John Berger famously observed in Ways of Seeing (1972): A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father…

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus, she turns herself into an object, and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.

The women in Samman’s paintings, however, are not posed to instruct or provoke. Their gaze turns inward, anchored in something sacred and deeply personal. Sometimes their eyes are closed, sometimes they look beyond us, but never directly at us. There is no invitation to be viewed; rather, there is only the option to witness, if we are willing to look with care.

One thing becomes uncannily clear when engaging with Samman’s work: imagination carries a radical charge. It moves with defiance like a quiet, deliberate force. I believe there is something profoundly subversive, even threatening to the oppressor, in the act of envisioning a new world while standing in the ruins of the old. The fragmented political landscapes we’ve come to know so intimately feel like terrains of fear, loss, and fracture, which are often inherited without choice. Etched into the timelines of our families and histories, they creep into our becoming, too. But Samman captures the power of the alternative. She explains that “imagination is a tool of resistance, one that can construct an ethical worldview, one that defies the cycles of history and offers an alternative vision.” Her paintings summon futures shaped by tenderness and sacred possibility, where the fruits of Jannah and the serenity of a sky unbroken by noise or threat feel startlingly close, as though one might reach up and hold that sky between their palms.

“imagination is a tool of resistance, one that can construct an ethical worldview, one that defies the cycles of history and offers an alternative vision.

Samman shares that What Music Feels Like, the piece that compelled me to reach out to her to begin with, is her most sentimental piece. “I remember sitting in a café, trying to find a way to express my love for home. I kept comparing that feeling to music. Music is impossible to describe. It’s something we can’t touch, but feel so deeply. That mystery reminded me of how I experience home: intangible, but everywhere inside me. So, the painting began with the title What Music Feels Like, and I built the world around it.”

In both music and home, there is a shared language of sensation: one that bypasses logic and speaks directly to the body. In this way, What Music Feels Like crystallises much of what underpins Samman’s wider practice: the desire to visualise the unseen forces that decorate a memory, to hold space for sensation without needing to define it. The painting becomes an act of faith in feeling, and in doing so, invites the viewer to surrender certainty, and listen. The fact that the painting began with a title places it firmly within the logic of storytelling. It reminds us that perception is never static, that reality is not just what’s visible under the spotlight, but also what flickers in its periphery. Home, then, is not anchored in place, but performed again and again in the theatre of the mind.

“For me, music feels like home,” she says. “And home, in this dreamscape, is built through the senses; pomegranate as taste, sand as touch, jasmine flowers as smell. If home were an image, it would be this. It holds everything I love.”

Similarly, Samman shares that the title for the painting, We Need A Miracle, came to mind before the first brush stroke. I kept returning to this title, as it carried both faith and yearning. Acknowledgement of hope blended with urgency, and naturally, that resonated. “I made it during a very dark time”, she says, referring to the start of the genocide in Gaza. “I couldn’t stop thinking about their resilience. It was spiritual, like they could see something we couldn’t. That’s what led me to imagine this other world, one that might be just beneath our feet. The painting is about hope. The irony of a man fishing in the desert, what could he possibly find? But beneath him, there’s a whole unseen world. Right now, it feels like we are all fishing in a desert.”

Faith, as an unseen force, is that final territory no empire can conquer. Colonisers may seize homes, land, food, even children and lives, but they cannot occupy the inner sanctum where belief, memory, and hope quietly reside. It speaks to faith as an ancient technology of the heart, one that helps us endure, imagine, and hold on to beauty even when the world turns unrecognisable. Samman continues, “What they don’t realise is that we have faith. And without faith and hope, love dies, and the enemy wins.”

Often, nostalgia is not just a longing for the past itself, but for the version of the self who once lived it. It’s usually conveyed as time travel, but here in Samman’s work, nostalgia is more about psychic excavation: a return to viewing the world through the boundless and often, radical whimsy of the child. In that sense, Samman’s paintings remind the viewer that perception, like memory, is fluid, layered, and deeply subjective. And that in returning to the imagined landscapes of childhood, one might not only recover what was lost, but glimpse who they were before the world taught them how to see.