News

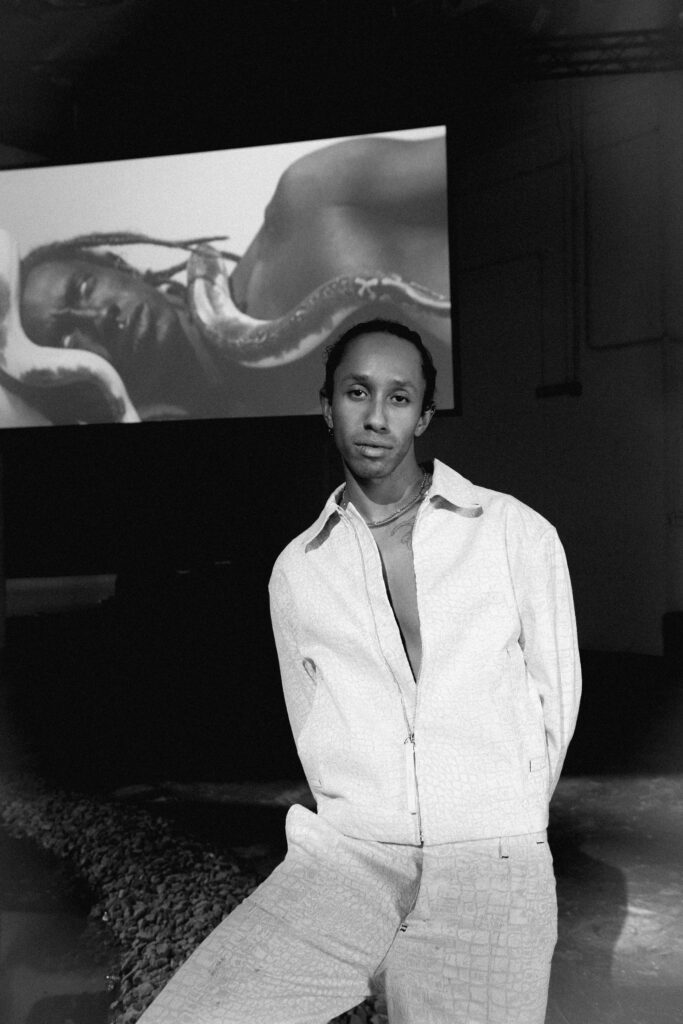

Photography: Raghe Farah

Fashion Director: Kim Payne

Fashion Assistant: Ali Ammar

Producer: Fatima Mourad

Location: ICD Brookfield Place in Dubai

Two bodies sit silently on reflective boxes, positioned within a small round puddle framed by stones. A snake rests languidly on their shoulders, stretched taut between them like a living thread. Their eyes are opaque white, void of sight, while six vast screens hover above, encircling them with sprawling desert vistas from the UAE to Morocco. This is Le Miroir, the latest performance by Miles Greenberg, commissioned by and presented at ICD Brookfield Place in Dubai, a work that carries many firsts: his first performance in Morocco, his first in the UAE, and, intriguingly, his first film, despite his extensive video work. “This piece feels different, though,” Greenberg admits. “The reason I’m calling it my ‘first film’ is that the process, the structure, the way I edited it, the way we shot it, were all much more narrative than in my other videos. I’m self-taught, but I do 95% of my editing myself, and I’ve gotten much more skilled over time. I was obsessing over Tarkovsky when I was editing this piece. I would take editing breaks every couple [of] hours, often around 3 or 4 AM, and read his diaries during the period he was making Mirror in the 70s.”

Tarkovsky’s Mirror is renowned for its poetic fragmentation and philosophical depth, its refusal to follow conventional narrative logic. Greenberg’s Le Miroir, unfolding across contrasting geographies from Marrakech to the UAE desert, evokes a similar blurring of memory, place, and movement. Although the mediums differ, Tarkovsky’s cinema versus Greenberg’s physical performance, both artists share a profound sensitivity to time, ritual, and emotion that resists easy storytelling. Whether Le Miroir consciously honours Tarkovsky or simply resonates on parallel frequencies, it creates a rare space where the spiritual and somatic balance delicately, and structure gives way to sensation.

The six-hour durational performance featured JeanPaul Paula, Greenberg’s longtime collaborator, both seated on their reflective boxes, engaging in sustained, minimal physical actions that invite the audience into a shared, contemplative experience. “Jean Paul and I have collaborated several times since our first encounter in 2019, working on my Palais de Tokyo residency show. He’s become like a big brother. We barely even spoke about the performance before we did it, because we already knew what it was going to be. I like working with people who understand me nonverbally.” This preference for nonverbal communication seems fitting and essential to Greenberg’s practice, where the body becomes a vessel of expression beyond words. He deliberately refrains from discussing his emotions or thought process during his performances when asked, allowing space for the audience’s own interpretations and emotions without “cheapening the piece or killing anyone’s experience by trying to grasp for words I don’t have.”

There is an elusive quality to Le Miroir, an illusion of presence that remains just beyond reach. The performers’ minimal movements, the blank white eyes, and the slow, deliberate presence of the snake all contribute to a palpable tension between what is seen and what is felt. This is the allure of performance art: it provokes sensations that everyday life rarely stirs. The full presence of the artist extends an invitation to be fully present as well, weaving the audience into the performance’s living energy. Marina Abramović, a seminal figure in performance art who profoundly influenced Greenberg from the age of twelve, famously said: “The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, and to elevate the mind.”

Greenberg first encountered Abramović’s work with The Artist Is Present at age 12, a formative experience that profoundly shaped his trajectory, eventually leading to her mentorship and ongoing collaboration. In a similarly prophetic arc, his ties to the Venice Biennale also run deep: his mother attended while pregnant with him, and decades later, he returned to perform Sebastian there in 2024, with his mother playing a small part in the performance. When asked whether he sees these moments as full-circle revelations or manifestations of a personal prophecy steering his artistic path, he replies with a succinct “Yes.”

It was this powerful performance that led ICD Brookfield Place Arts curator Malak Abu Qaoud to invite Greenberg to Dubai. “I don’t come across work that much that really pushes me and makes me feel a lot of emotions,” she says. “He spends a lot of time pushing his body to these limits and these beautiful sculptures. It’s very rare that you meet someone that really embodies what they are. He is the artist.”

Having watched his performance and later met him at our photoshoot, there’s truth to what Abu Qaoud said. Sure, he wasn’t the white-eyed bare-chested living sculpture I was beholding the day before; he was beaming, light-hearted, almost butterfly-like in his energy. But he was an artist still, in the intentionality of every movement, no matter how small; in the way he posed; in how fully present he was with us.

Towards the end of 2024, Abu Qaoud reached out to explore a collaboration. By then, Greenberg had already been approached by 1-54 Marrakech, the non-profit contemporary African art fair. The timing aligned. Together, commissioned by ICD Brookfield Place, they envisioned a dual performance: ACT I would be staged and filmed in the majestic El Badi Palace in Marrakech, followed just two days later by ACT II in the vast expanse of the UAE desert. The two performances were then edited together and projected across screens during his Le Miroir performance at ICD Brookfield Place.

“This was my first time visiting Morocco, and my first time doing more than a layover in the UAE,” he tells me. “But one very formative experience I had in the region was visiting Egypt as a 13-year-old. Cairo blew my mind.”

![]()

“I had an obsession with Ancient Egypt as a kid,” he continues. “I didn’t think I really looked like either of my parents at the time, and neither of them grew up with their biological families, so there were a lot of missing links in my ancestry. And in lieu of context on where I came from, depictions of Ancient Egyptians through popular culture (there was a book in my school library which I would pore over all the time…) were the first place where I felt like I saw people that I vaguely resembled. There was something so elegant about them to me; I learned everything about their beliefs and culture, I fantasised about it a lot. So when I visited the pyramids of Giza (which were about forty times larger than I anticipated), my imagination really exploded. Anyway, two years ago I finally found out I’m a mix of Brazilian, Ukrainian, and Irish and Black American (and zero per cent Egyptian), but the fantasy lives on nevertheless.”

While performance art remains a relatively niche practice in the Middle East, ICD Brookfield Place’s commissioning of Le Miroir signals a push to expand local horizons. Abu-Qaoud remarks on the art form’s immediacy and unpredictability: “Even if you plan it, you script it, you produce it, it’s all based on the moment, how you react to the snake, how they’re both reacting to one another, to the space itself.” Greenberg concurs, pointing to performance’s universality rooted in ritual practices found in every culture, including abundant pagan and Abrahamic rituals in this region.

“Performance art has as much universality and precedent as painting or sculpture does, just not always at the forefront. For me, I’ve never really seen a big difference.”

The parallels between ritual repetition and performance are evident in Greenberg’s work. Many regional rituals, especially Sufi ones, rely on repetition of movement and speech to induce trance states, much like the looping desert imagery projected around Le Miroir. The repetition and duration push both body and mind to limits that transform perception. Greenberg’s earlier pieces attest to this, such as Lepidopterophobia Exercise (2020), where he sat immobile in a glass cube filled with atlas moths for five hours, and Oysterknife (2020), a 24-hour non-stop treadmill walk during lockdown, inspired by the tragic death of Ahmaud Arbery in the same year.

Greenberg explains his post-performance rituals with a blend of humour and candour. “I either go out and party until 5 AM or I curl up and watch something like Golden Girls. Both those pieces were in the middle of COVID, so there was no party to be had, but after Sebastian (2024), an eight hour piece where I had real arrows stabbed through my skin, my team and friends all went straight out to Björk’s DJ set and we danced till 8 AM the next day, arrow wounds still healing. It’s called having range!” And range, indeed, he has.

“I either go out and party until 5 AM or I curl up and watch something like Golden Girls.”

For Greenberg, the essence lies in the body’s autonomic movements, the subtle, unscripted gestures that reveal the true subject. “I’m not very interested in movement that’s too staged or ornamental. When you’re at the end of a durational piece, there’s not much artifice left; you’re not performing anymore, really. It’s just you, standing there with your spirit right at the surface.”

![]()