News

Set in the 1960s, there is a moment in the 2021 Wes Anderson film The French Dispatch when art dealer Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody) attempts an exchange. The trade involves convincing inmate Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) to sell him his painting and allow him to act as his agent. The painting is supposedly a portrait, but the tableau is a flurry of fleshy hues set in an abyss, forming an abstract composition that resembles no one. Rosenthaler was once a gifted student of figurative painting before his descent into mental illness led him to a life in a French prison. Cadazio presses him: “It’s what makes you an artist. Selling it.” Real-life international art dealer Joseph Duveen was the inspiration for Cadazio’s Svengali-like character.

Joseph Duveen brought crown jewels from Europe to the nouveau riche of America’s Gilded Age, attracting New World arrivistes with no family heirlooms. If one could not become old money, they could at least acquire old-world aesthetics—Dutch Masters’ paintings, dark woods, and ivory. Duveen had fox-like instincts for the power of a good story in making a sale, and if it was a true story, all the better.

This fictional scene illustrates two truths: that the 1960s marked a seismic shift in how society valued artistic merit, as the first truly modern masterpieces were being created, and that their commercial value has often been linked to spectacle. Rosenthaler’s life’s work in the film becomes known as The Concrete Masterpiece—a vista of Mark Rothko-style tableaus painted directly onto a prison wall, with warm hues transformed by a rough, biscuity texture.

The press and critics flock to the prison, while an eccentric, Peggy Guggenheim-esque art collector purchases the artwork and personally arranges to courier the entire prison wall in situ back home using a “twelve-engine artillery transport.” It is a moment of farce that is barely satirical when one considers some of modern art’s historic spectacles.

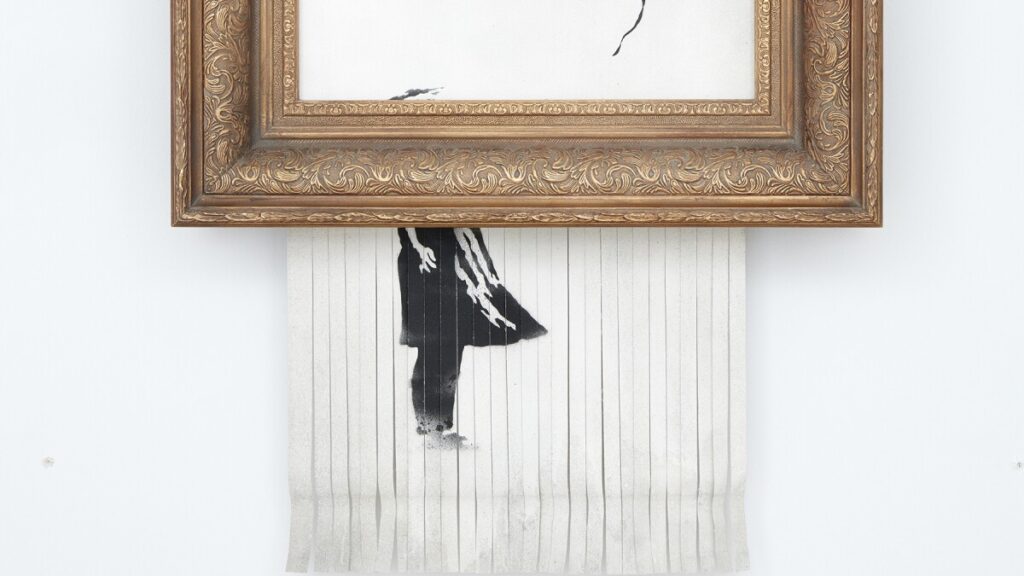

Recent films that lampoon the commercial art world, such as Velvet Buzzsaw (2019) and The Square (2017), take artistic license, but their moments of shock value often resemble social realism more than melodrama. Think of Banksy’s Girl with Balloon, which was shredded at auction in 2018 immediately after the bang of the gavel, having just sold for £1.04 million. The irony is that after the artist attempted to destroy it, the work—renamed Love Is in the Bin—was later resold for almost £10 million more than its original price, much to the glee of the auction house, which described it as “the first artwork to be created live at auction.”

What does this say about society’s desire to own art if the act of destroying a work becomes as or more valuable than its completion? This tension between art’s authenticity and assertions of artificiality is nothing new. It goes beyond aesthetic appreciation—proximity to something real, even if it unnerves us, is electrifying. The artist’s living vision is the true prize, even if that vision is volatile—like capturing lightning in a bottle.

This legacy of conceptualism and performance brings us back, once again, to modern art’s beginnings. One of the key reasons it was such a mind-bending time for society’s understanding of creativity was the optimism in unlearning the rules of the art historical canon—and then rewriting them.

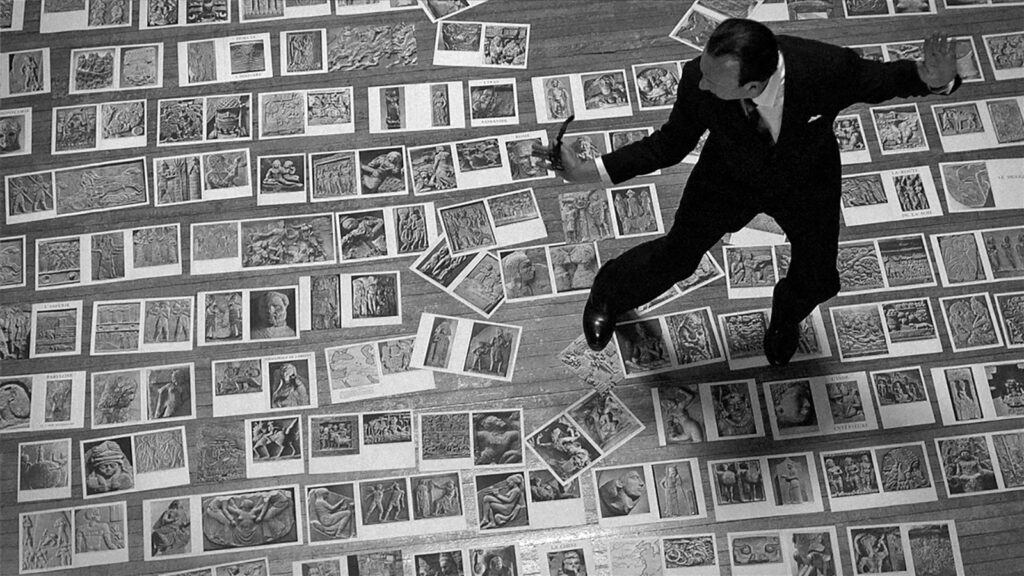

In his 1947 book The Psychology of Art, French art critic André Malraux notably introduced the concept of the Musée Imaginaire, or imaginary museum. His concept was misunderstood—some thought he meant to create a museum with empty walls, where visitors would imagine the artworks themselves, while others thought he was referring to a collection of photographs of great works of art.

Some thought of it as reproductions of great works of art from around the world, collected together. His essay argued that the sensory experience of having one’s favourite works of art from different disciplines and places congregated would ultimately always be a disappointment compared to the imagined ideal.

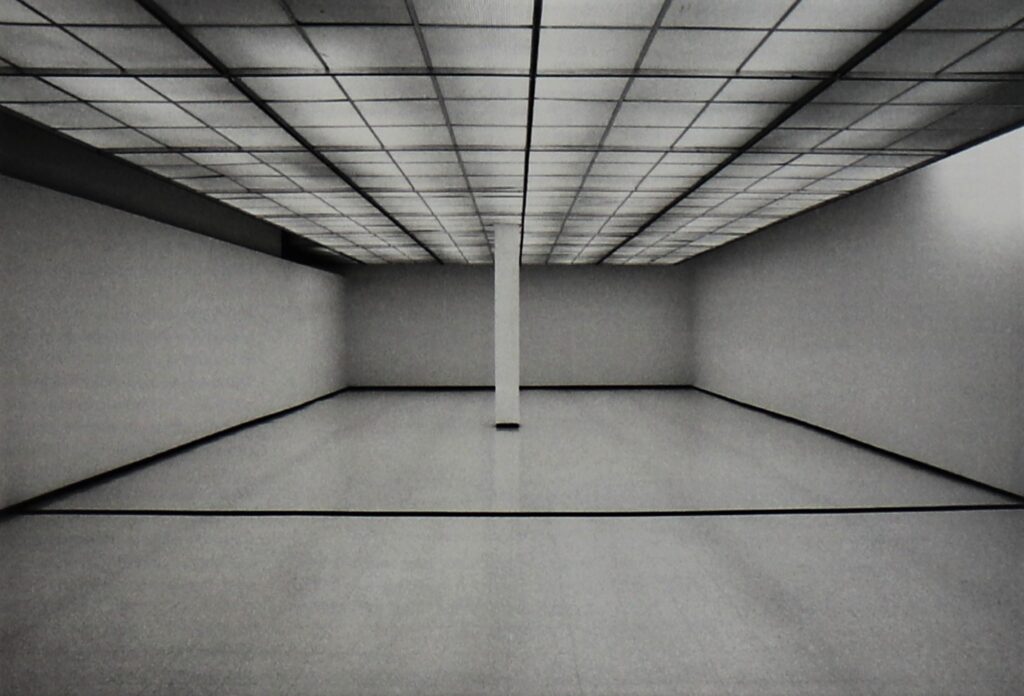

In 2012, the Hayward Gallery tested this theory with the exhibition Invisible: Art about the Unseen 1957–2012, which gathered invisible works by Andy Warhol and Yves Klein, charging entry for visitors to view Warhol’s 1985 piece Invisible Sculpture or Klein’s l’Architecture de l’Air. The Pompidou Centre famously staged a similar exhibition in 2009 called Voids, which featured empty walls patrolled by guards. Exhibitions like these make headlines for a reason.

More than just commodifying creativity, the degree of abstraction involved has made some feel that modern art is a scam. Yet this very abstraction is at the heart of conceptualism—alienating some audiences while captivating others.

Examples of monochrome paintings that have sold for vast sums in the past decade include Orange, Red, Yellow by American artist Mark Rothko, completed in 1961 and sold for $86.9 million, and Onement VI by Barnett Newman, previously owned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. It was bought over the phone for $44 million—$14 million above the asking price.

The popular HBO show Succession centres on a family dynasty struggling to hold onto its legacy. The 1961 painting associated with the show’s first-season poster, The Hunt for Tiger, Lion and Leopard, evokes an air of rot, dying empires and old-world dynasties. The Old Masters paintings once coveted by Duveen’s clientele take on a new meaning in contrast to the aesthetic preferences of today’s wealthy elite.

Now, Neo-Modernism reigns popular among the ultra-rich—its appeal lies in freshness: the cleaner the lines, the purer the form, the better. Fintech billionaires and crypto bros are devoted followers of a revivalist love for 1960s Bauhaus minimalism. Highly conceptual, minimalist paintings suggest that true intelligence lies in their multiple interpretations. A minimalist painting suggests that the viewer’s interpretation of the art is what makes them its master—as it is their imagination, their creativity that fills in the gaps.

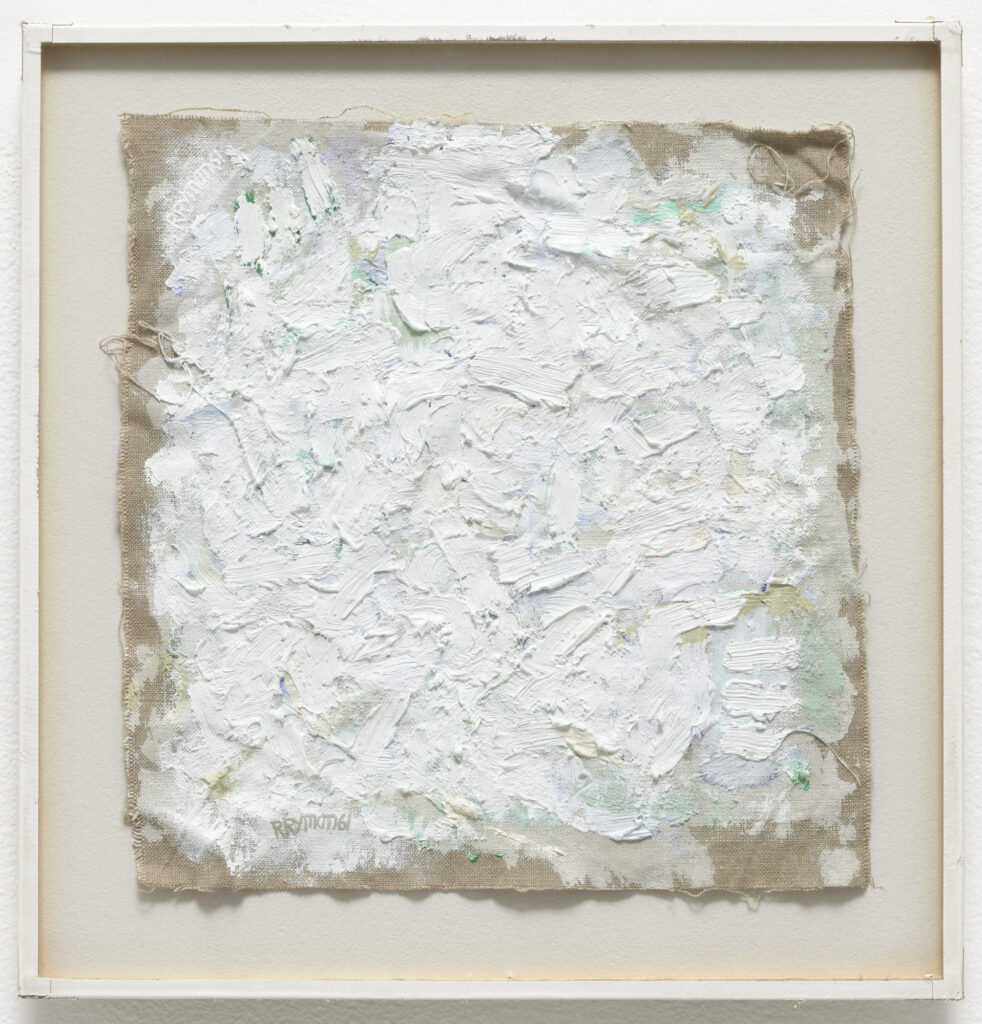

Duveen would have considered this a good story: a man named Robert Ryman, then a jazz musician, arrives in New York in 1963 from Tennessee and works as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for seven years. Ryman would go on to become an acclaimed artist, with his works eventually displayed within MoMA’s walls. In 2014, one of his early canvases sold for $15 million at auction.

In 1972, he created modular white paintings on white canvases—an aesthetic in which the frame and the wall itself became part of the experience. This was an era that celebrated art and experimentation, just a year before Andy Warhol’s Factory opened on East 47th Street.

His experimentation with painting during this period was deeply informed by his background in jazz music. Like jazz improvisation, Ryman became obsessed with the questions of when a painting begins and when a work is truly complete. He approached painting methodically, listing the materials first—the paints, brushes, and mounts—as the starting point.

“Each painter’s way of seeing is part of his perspective and they should allow you to see how they see. Completing a painting is presenting the painting in the world in a way that makes the aesthetics clear is an important step. The painting must be correctly seen in order for it to be complete.” By Ryman’s estimation, many uncompleted paintings hang on the walls of the world’s art museums.

In a 1993 film, he explored the power of articulating artistic vision through technique, discussing the distinctions between representation, abstraction, and concrete painting: “We are all familiar with the first procedure, representation. It is what we see almost everywhere. Abstraction is the second procedure. It gave painters a new dimension, a way to expand the picture. There is a third procedure that has been called concrete painting, absolute painting. I call it realism. With realism, there is no picture, narrative or myth. Spaces, lines and surfaces are real. Realism uses all the same devices as representation and abstraction, but it does not use illusion.”

Ryman illustrates how effective a painting can be at presenting its audience with a whole world—not just within its frame but including it. With Ryman’s realism, the artist offers a perspective through inventive use of colour and texture, offering two ways to read art at once.

Consider the fact that 30 years earlier, people would have seen his white paintings as too conceptualist for a general audience at that time, if not a full-blown hoax: white paint on white canvases! But truly, analysing a white painting is a creative exercise. It requires the audience to have patience, to really consider the details of what they are looking at, where the painting meets the wall; whether there is really light reflected on the canvas, not its representation.

In this era, the colour white has a lot of possibilities as a reference. White is not the absence of colour but the presence of all the colours on the light spectrum at once. There is a renewed fervour for rethinking old ideas, and going back to a blank canvas. The spirit of tabula rasa, Latin for “blank slate,” is a term popularised by British philosopher John Locke. He emphasised the idea that all human knowledge comes from sensory experiences, that we are a blank canvas awaiting the world’s impressions. The illusion of emptiness emphasises our search for meaning, and when this comes to art, it is up to the viewer to work out what they are looking for.