News

![]()

“What’s it like to be a marine-altered person?” I asked, tasting disbelief on successive words I’d never anticipated uttering for work.

“Marine-adjusted person,” my interviewee corrected me, grinning.

Conversing with internet-famous multidisciplinary performance artist Vita Kari (they/them) is marked by this kind of knowing absurdity. My question stemmed from their recent video series, which fictionalises a kind of post-apocalyptic universe where the aquatic undead roam Earth. The lore is sort of slippery here, but we do know that love lives on (there’s Bubble instead of Bumble), mer-people survive on daily doses of Iodine (??), and influencers remain undead and extremely online. “So I, now as Vita, am playing this character of an unbothered iodine-taking influencer, because that’s what I think would happen if there was an apocalyptic situation… like, it would be so unserious.”

@vitakari Replying to @Ella #marineadjusted

A cursory scroll through Vita’s Instagram feels like being temporarily yanked into a fever dream. It’s an illusory minefield, their videos orphans of any perceptible plot or context. But greeting me on Google Meet, draped in beaded jewellery and a hot pink cardigan, the smoke and mirrors of their zany internet persona readily dissipate. They’re as sincere and self-aware in conversation as they are chaotic and confusing online. “If my work isn’t divisive, I’m not doing my job,” they declare. “I want people to have an emotional opinion about my work; not in a way that’s inflammatory, but like for something as simple as this undead aquatic series, I’m interested in how there’s a Hunger Games conversation going on in the comments.”

Vita has the kind of sun-drenched aura only a Los Angeles upbringing could foster. They’re thirty (“and I’m still pulling all nighters, dude”), deaf/hard-of-hearing (HoH), and a sibling to many; they worshipped their grandmother (“I’ve clipped that woman’s toenails!”); they enjoy red lipstick; they’re chronically online. “The key for me to have good ideas is that I have to be consuming absurd amounts of media at all times,” they note. “Like if I was just left alone in the forest, I would have no ideas. I need to be surrounded by the creative community. That’s why I love the internet so much, because I’m inundated with so much media that it’s impossible not to start thinking, ‘Okay, what have I not seen?’”

As long as they have known, Vita has always been artistically inclined. In high school, they won a Vans shoe design competition, took every advanced visual arts class available, and landed a scholarship to NYU, where they were actually on the pre-med track. Parental (and grandparental) expectations to pursue the usual assortment of practical professions—“doctor, lawyer, right?”, giving me the fellow-diaspora nod—meant they were juggling a credit-concoction of biology and organic chemistry alongside arts. “It was really hard, I didn’t last, and I ended up transferring,” they admitted, describing how they moved back down the coast after a year and a half of snow, stress, and New York’s egregious living fees. “NYU was amazing because I made an amazing friend, and it was so expensive, oh my God, it was so expensive! I don’t know how anybody does New York.”

It was at their next university in North Carolina, where they studied visual arts, that they were forced into a reckoning. Explaining the heinous treatment they received for the alternative aspects of their identity, the origins of the sidewalk grit that pierced their otherwise sunny self-mythology became clear. Not only were they the target of blatant homophobic hate speech, they faced unprecedented hurls of (just confusing) racial slurs as a result of being misapprehended as Latinx. “That was when I realised representation is really important,” they said. “For me, it was really important to realise that showing up as an artist and showing up on the internet is actually important, because taking up space is something I should be allowed to do.” While representation felt optional and trite for them in LA, it was very clearly urgent elsewhere. “I think that representation can sometimes feel ‘cringe,’ but it’s actually so important, especially in spaces where I took it for granted… It really gave me perspective, so I think that’s when I first was like ‘Oh no, I’m going to show up as an artist, for sure.’”

Despite these bruising instances, Vita adored the South’s community-driven spirit, and lingered in Atlanta and Nashville for a while after graduating. But by 2019, they were back in LA, where they co-founded VITAWOOD—a queer community art space launched in a warehouse during the tumult of the pandemic. “Everything was so cheap. No businesses were functioning,” they expound that this was where they began performing pop music with strange props and uncanny interactions. “I was doing music at the time for funzies, and I really hate singing but I love the performance aspect. We would go up and do weird things with the audience and make people kind of uncomfortable—not in a sinister way, but there was something so fun about the audience participation… I was like, this is so fun. I want to do more of this. And I just didn’t have the language as to what it was, but it was performance work.”

Their breakout performance piece came in 2023 with Trapped in a Can, a staging outside Art Basel Miami. They constructed a human-sized tin can, climbed inside, and shrieked relentlessly while their managers and friends handed out branded water cans like it was influencer PR. “I had a can with me screaming on it,” they say, unfazed. I try to school my face into unconcerned neutrality as they explain that people were invited to throw the cans at them. “It got really bizarre. Like people, if given a can, will truly do whatever they want with it. It was really interesting, and we ended up raising money for water inequity.”

So began a string of creative and chaotic enactments, in real life and on the internet; all absurdly meta, socially attuned performance acts. Their 2023 online series The Craziest Thing About Being Creative toyed with the nature of virality and visibility. Luring in tens of millions of views, the videos featured familiar TikTok cues, like valley-girl narration and beauty routines, only to subvert them using printed props that mimic digital effects, like paper hands and captions. Conflating illusion, performance, and satire, Vita forcibly jerks their watchers from brain-rot voyeurism. “I did not think it was going to last this long,” they profess. “But my idea with it was I wanted to interrupt the doom scroll and I wanted to get something to stop the feed, to suspend reality and remind us, like, what are we doing on our phones?”

@vitakari

Like in their construction of the alternative world of aquatic undead, Vita regards their entire practice as a response to lying outside the margins as a queer, non-binary artist with sudden hearing loss. “I have hearing loss, and I wear visible hearing aids, and that’s part of my life every day. So people that see that or have watched my videos know I have a visible disability. Ultimately, watching my videos, you can’t not see the parallels with disability, queerness, racism, whatever you want to say that these videos have. For me, they were first inspired by having a visible disability; having to navigate hearing loss. But after time, seeing how people pick up on things… They help world-build.”

It’s a participatory and reciprocal form of performance art. Perplexity may feel like an admission ticket for their work, but it’s more so an invitation for their audience to contribute their perspectives and apply interpretations. Rather than underestimating their viewers, and largely unbothered by mass confusion in the comments, Vita focuses instead on those who feed the universe, nourish their ideas and grant them viewership through prisms of amused irony. “I’m only a few videos into the series, and what surprised me is how fast people came around to it, because even with the confusion people are answering like ‘We think that this is happening, and there’s a history of this, and actually this character is HoH,’ and I was like, ‘Yeah. That.’” They explain that commentators supplement lore, and their perspectives become fodder for new ideas. “And what they don’t know is that I’m looking for ideas in the comments!”

Their social media is a liberated dimension where any and all explanation is necessarily absent. This was a learned omission for Vita: “In grad school, there was a pushback on being too didactic, like understanding the work too easily,” they clarify. “So I think I’m trained to allow others to [fill in the gaps]. I don’t underestimate my audience… I believe in them.” The seed for their ideas mainly stems from their search for gaps in the stories they enjoy. “It’s consuming tons of media and then just being like, what would I rather be watching? Like I was watching ‘The Last of Us,’ and I’m like: What do I want from this right now? I want the lore. Like, what are these people infected with? What do I want from this?”

Peculiarity seems to be the most notable currency of the performance art realm. One of Vita’s inspirations includes the transgressive likes of Andrea Fraser, who is best known for giving lectures in museums and then stripping naked mid-talk. They also shout out their friend Joaquin Stacey-Calle, who once ran on a treadmill for the entire duration it takes to ferment bread. “How does someone even think of that?” They marvel. “I’ve never even fermented anything!”

But their own performative art tends to live on social media, clips that mutate and circulate relentlessly in that great void. “I do believe the viral video can be seen in time and performance, and that’s because of all of the comments and everything that goes into it; the replicating, the recycling of the video, the cropping. I think all of those things go into what performance work is, which is cycling, and how that video has a new being. That’s why I was interested in the loss of personhood that comes with becoming a meme.”

I asked Vita if they felt they had ever lost their personhood, given that they themselves became a meme at one point (see them on KnowYourMeme.com). “I was like, I did it, I became the Craziest Thing About Being a Creative,” they beam in detached reflection. “Like I was faceless as an entity at that moment. But now I’m an artist again, a person again. I’m on to other projects. But for a moment, that was interesting.”

![]()

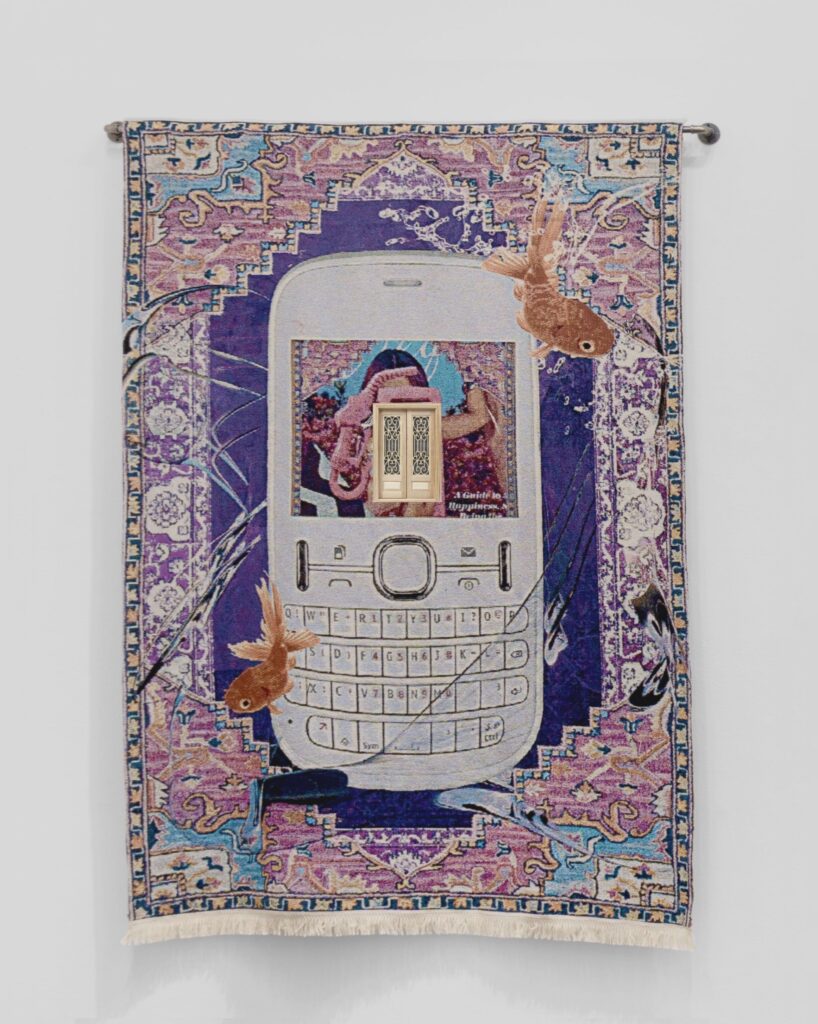

Vita is a true digital native, speaking in spirals of self-aware irony, critique, and care. Their textile practice hosts this hybridity; the rugs they create are half-machine, half-human-made. After their grandmother Rita, a stubborn but beloved Sephardic woman who settled in the United States in 1951, passed away, Vita inherited her records and diversity of fabrics. “This woman had so many textiles, I can’t even tell you,” they gush. “She had a textile of Paris—she’d never been to Paris, but she got it in Turkey or something. Or at least, it was Turkish. I wanted to honour her in my work.” They were intent on this dedication, unconditionally, despite their grandmother’s total bafflement towards their endeavours and identity. “She didn’t get the art thing at all, she had no understanding of it.”

Existing in an unsurprising material illusion, Vita’s rugs gesture toward some vague ‘ethnic’ anchoring, despite being deliberately sourced from mass-market furniture sites like Wayfair. “It’s from a stock image database; I bought the rights to it,” they affirm, explaining it speaks to the disembodiment that comes with circulation; meme or rug, it’s all the same. “It’s kind of a cultural flattening about how aesthetics are passed around like memes, losing selfhood.” Digitally woven, CMYK-printed, then painted top to bottom by hand, the textiles take a month for Vita to complete. “The textiles are digitally woven, and another part of it is the screen kind of similar functions to the loom. The loom is a grid, and if you zoom in really close to the screen, you’ll see a screen is built up very similarly, like CMYK, and digital printed tapestry is the exact same thing… if you really unweave all of them, they have at the base CMYK, digitally printed textiles.”

Despite being undeniably skilled as a painter, Vita frequently deflects attention from their technique. But their rugs speak volumes in all their layers of rich, saturated colour and minute detail, meticulous and painstaking constructions. In their 2024-2025 installation titled ‘Her Original Pixel,’ they displayed the textiles together, patterns glitched, unspooled and rewoven, mirroring the distortions of miscommunication and the experience of navigating the world as a Hard of Hearing artist. “Video making is my favourite form of art; I do love painting, but it’s a personal practice at the end of the day. I’ll use painting for my tapestries and maybe as a way to add on to performance work, but I’m not sure I’d put a painting up on a wall right now. Maybe I will. I might change, I’m very fluid in all my opinions,” they shrug.

There’s a level of care imbued in all their work that seems integral to their being. Vita tells me about being an anxious child with a constant stomach ache, the kind who once took care of a rock, convinced it was an egg. “I made a house for it, I nursed it to health, and I loved it so much, but it turns out it was a rock,” they recall. “I made it a tissue box house with a little bed. It was very serious, like we weren’t playing around. I don’t know why I thought it was appropriate for an egg, but we weren’t playing around.”

In another life, they explain they would’ve gone into elder care. In this one, they feed people, paint through the night, and nurse strange digital creatures into being. Still, the constant impulse to care is very perceptible: “If you come to my house, you will be fed,” they tell me. “You’ll leave fed and with stuff that you never knew you wanted, like skincare products. Who knows what you’ll get!”

With all the warmth and whimsy they readily offer, their humility makes the accolades seem almost incidental. In 2024, Vita completed their Master’s in Fine Arts at Otis College of Art and Design. Since then, they’ve exhibited at Good Mother Gallery, Bolsky Gallery, and Yiwei Gallery in Los Angeles and China. They are set to debut at Untitled Miami this December. They’ve worked with brands like Marc Jacobs, LOEWE, Google, Adobe, and Spotify, and have been featured in the likes of Forbes and Interview Magazine. They’ve spoken at UCLA and Conde Nast College. “I have a dog, but I don’t have kids or anything,” they say. “So my art is my child, it’s my everything. I sacrifice everything for it.”

Call it gimmicky or deceptive, but Vita is only pulling back the curtain on the glaring illusion that is the internet. They recognise the digital realm as a theatre, with viewers and commentators packed, leering in the dark of it as spectators. They know that virality is form. “It’s a performance online; we are all always performing.”

![]()