News

ACT I

You wouldn’t even notice it, domesticated and stark, a less-than-regular residential building. When the city of Ramallah attempted development and civility, it demolished its old homes and sold its precious ripe stone to replace with one bought in bulk and built, in the dozen, ghostly coffins—pale and yellowish, the shade of a retirement home wall; that’s what it did at least, in the case of François abu Salem. He was found buried under a load of sand from a bulldozer that continued its job building livable tombstones, not realising that the godfather of Palestinian theatre had just left us.

I had looked for this building like it’s my job to resurrect the dead. How does the godfather of Palestinian theatre perform his final act without his last stage turned into a coliseum? How does a country go on knowing it might have murdered its beating heart? How does a mother wake up in the morning to whip up breakfast for her kids, knowing this very building, right where she stands on the regular, hosted Palestine’s ultimate and only, real performance? We’ve paved over him, like we’ve paved over everything else.

Like François abu Salem would always say: theatre came a hundred years early to Palestine, except, I believe, the countdown, like this continuous cycle of repellent construction, starts from the ground up every day.

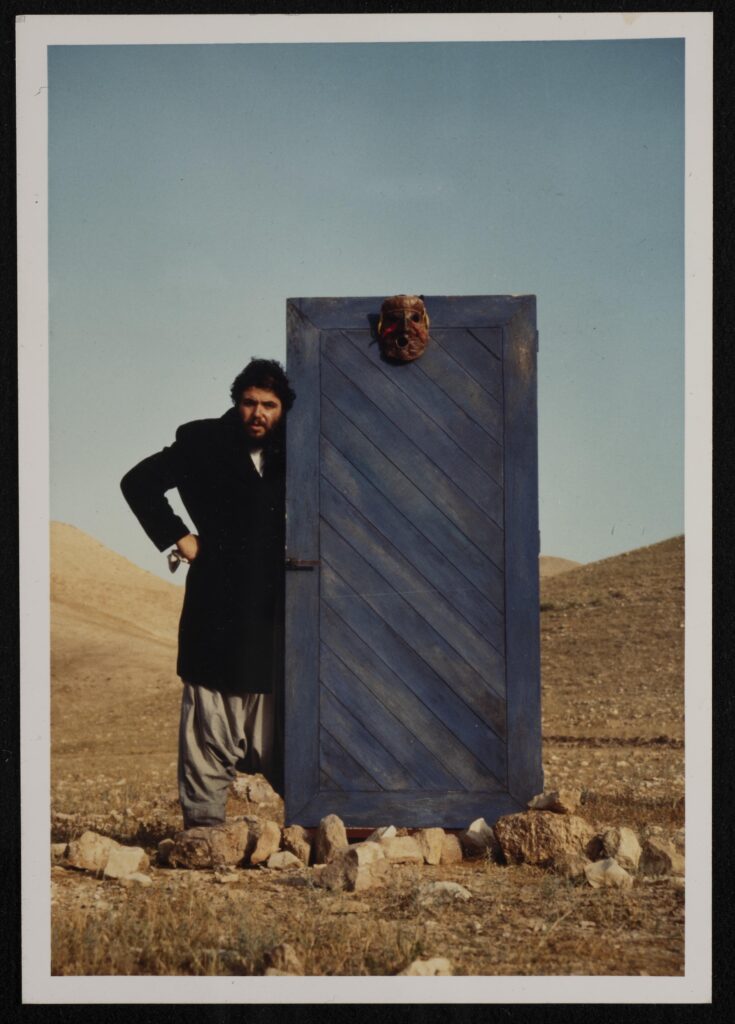

He was a theatre fanatic, performer through and through, and devoted with all his might. A virtuoso. Hard to explain, hard-headed, and hard to be around. Brilliant to the point of narcissism. François abu Salem was one of those you wouldn’t understand, might disregard and claim crazy. He was fantastical, unearthly. He was extreme, rigid, and uncompromising, but never arrogant, and generous to the point of rupture. A true intellect. He believed culture was a responsibility, and the intellect was the core of man. He would not only build the first professional stage company in Jerusalem, El-Hakawati, but he also trained everyone who knows anything about theatre today in the country.

“Before I met François, I was illiterate. I would see him as a 15-year-old in Jerusalem and wonder every time how come a French man speaks fluent Arabic. Years later, I was with him in France for three years; there, my life was changed forever. François took me to hundreds of exhibitions and plays and gave me tens of books to read. He taught me everything like you would teach your baby how to take his very first steps,” Amer Khalil tells me, who started as a technician for El-Hakawati, to then become an actor within the group and now the director of the theatre in Jerusalem.

But that is the tragedy of the intellect, the real and true intellect. In his last few years, before his final bow, jumping from a building under construction on the first of October in 2011 in Ramallah, François abu Salem was unsatisfied, broken by a country in a continuous decline. Despite an abundant number of plays and opera productions, two films, multiple European tours, endless big-name magazine features, and a hefty and long resume, François declared emotional and professional bankruptcy. The years François spent fostering an elegant and enlightened theatre movement, all to him, amounted to nothing. The world comes crashing down when it hasn’t turned out as imagined.

ACT II

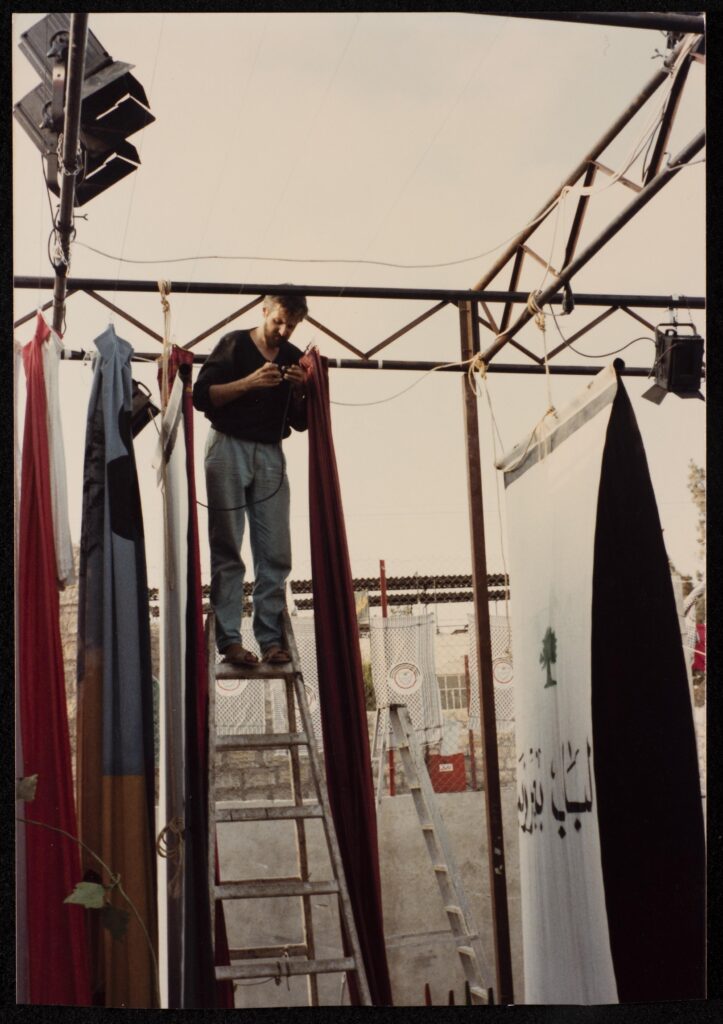

It turns out, after gutting and reconstructing, by hand, Cinema Raghdan in Jerusalem, which was set on fire twice by extremists for showing pornography, and opening the doors to the first and still perhaps only professional theatre in Jerusalem in 1984, El-Hakawati, the rug was to be pulled from underneath François abu Salem. Bureaucracy in action. And he was the kind of cultural madness that scares bureaucrats.

It was claimed the theatre is to become a national theatre, and François, anyway, wasn’t François abu Salem, he is François Gaspar, son of artist Francine Ternynck and Hungarian–born French poet Lorand Gaspar. Lorand was assigned a surgeon in Jerusalem in 1954 and would secretly treat freedom fighters (fedayeen) in his horse stable during the 1967 Naksa, leading to his deportation. François, only 16 years old at the time, fought the deportation order and insisted on being Palestinian, and he was, he was Palestinian, whether by choice or not, he was ours.

Although a Jerusalemite like no other, he was declared an outsider. A foreigner, they said. A guest. A temporary custodian of a project that no longer needed him, only his blueprints. For years, he insisted, torn between identities, on his seemingly denied Palestinian-ism, and at the end, with only his typical red sandals and his French passport, he carried touring Ramallah for a round of final goodbyes, he would die like they always wanted him to, François Gaspar. But isn’t this feeling of alienation one of the free? He was one to refuse dying from a heart attack or high cholesterol; he belonged to nothing, so the whole world was his.

“Francois’ character is reminiscent of a person who would grab a table at a party where everyone is laughing and dancing and just sit in the middle silent and downcast, it’s a constant performance with him and a cycle of attention, whether good or bad attention, he thrived on the shock factor and would always ask of us the craziest acts. For example, he’d say: ‘I want someone pissing on the stage during a play’ and we would be more than happy to do so but needing of a motif other than the pure shock of it,” says Emile Ashrawi, who founded Balalin theatre troupe (El-Hakawati predecessor) with François in 1971.

Like most of his plays, like Abu Ubu in the butchers’ market (2009), or Bism al-abb wa-l-umm wa-l-ibn (In the Name of the Father, the Mother, and the Son) (1978) where the disturbing and grotesque was the main drive, François abu Salem’s death was shocking, and a statement in and of itself. His student Amer Khalil, who drove around al-Tereh neighbourhood in Ramallah looking for a body that morning, described it as “a lesson”. He was an actor till his very last breath, and a teacher, like he had always been, he was saying something that maybe till the day nobody is to comprehend, but to him, he had finally found his answers, and he chose a leap from the tenth floor.

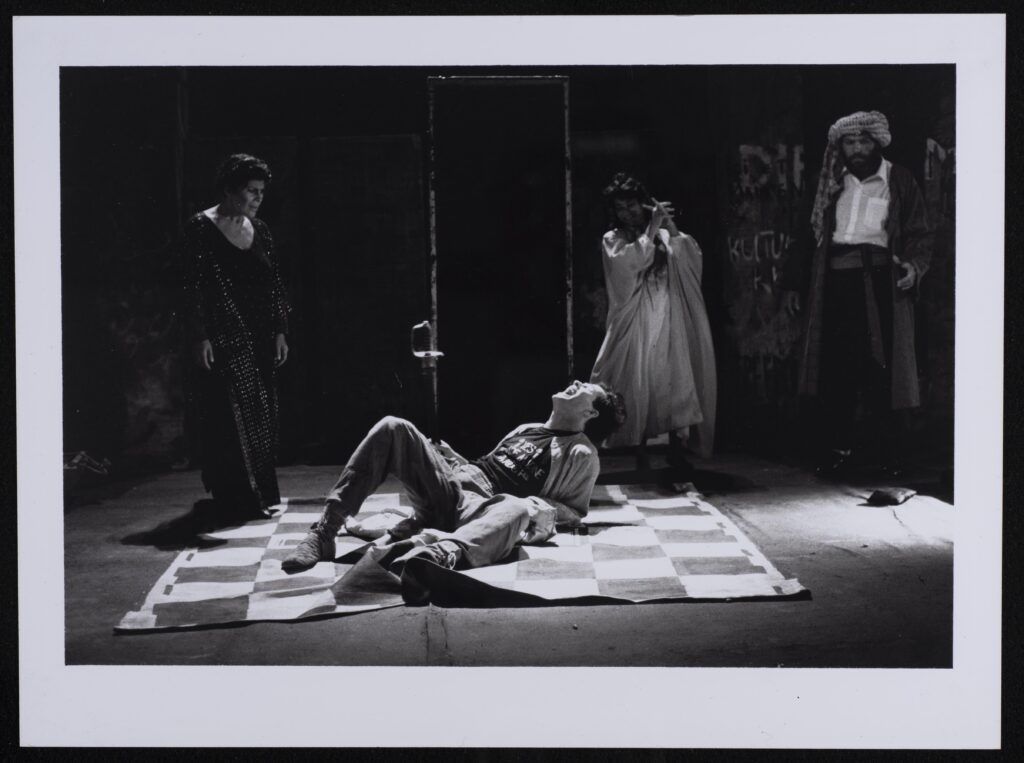

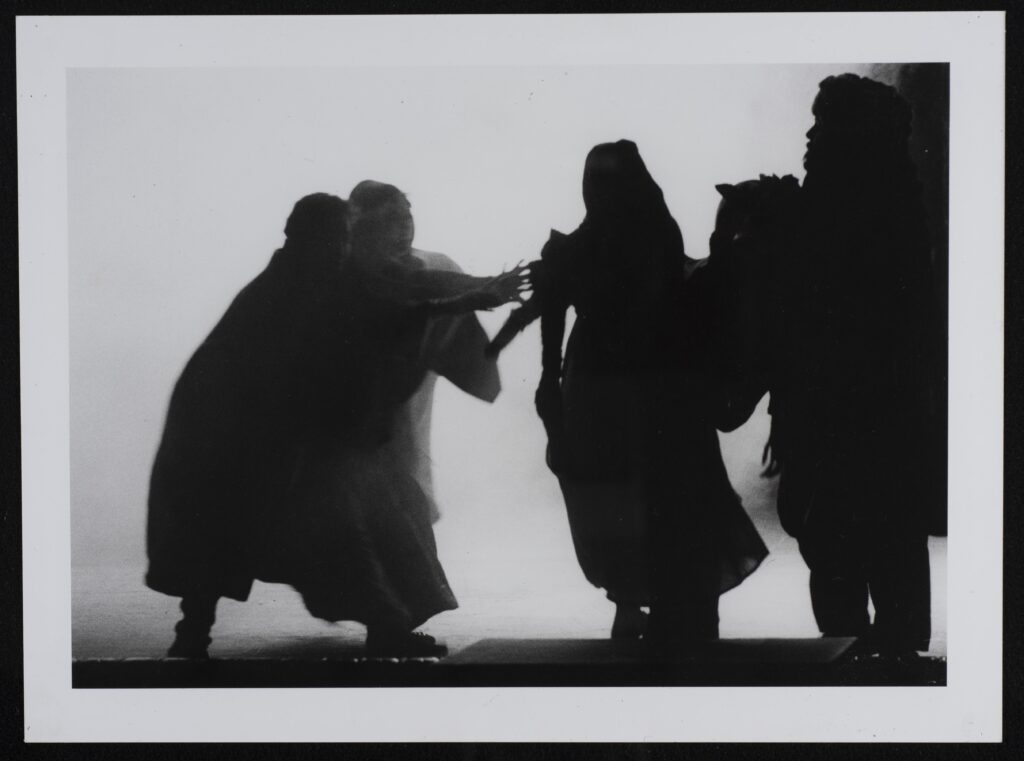

Founder of Ashtar Theatre in Ramallah and one of François’ friends whom he constructed El-Hakawati with, Edward Muallem, tells me: “François was a master at his body, that’s one of many thing we have learned from him and it explains why our first four plays as El-Hakawati group: Jalili ya ‘Ali (Ali the Galilean), Alf layla wa layla fi suq al-lahhamin (A Thousand and One Nights in the Meat Market), Mahjoub Mahjoub, and Bism al-abb wa-l-umm wa-l-ibn were touring Europe for months, we didn’t have to say a lot of words, our movement on stage was more than enough, we even improvised most of the script as we went on.” In that same logic, François’s movement that day was more than enough, it was absolutely alive, loud, and clearer than water.

ACT III

We like clear villains and clear martyrs. We don’t know what to do with contradictions. François was contradiction embodied: French but Palestinian. Chaotic but disciplined. Elite and earthy. Building and gutting. A borrowed last name (given to him by Emile’s brother Ibrahim Ashrawi in the early 70s) and a mystery for a birthplace. When looked up, the web swings between Bethlehem, Jerusalem, and France for his cradle. If you didn’t know him, you would think he is some sort of fictional character, like a prophet you’d believe in with conviction, and he was, in some sense, prophetic. That night must have been a prophecy and a clarity that he might have never arrived at before; it granted him a burial free of charge when before, rarely would anyone sponsor a production. These are countries built on the dreams of people who it kills. A holy land that ironically devours its prophets.

“Let them learn, I am not weak, as much as I can do something big, I can commit suicide, I will make the whole country shake, the path to fame is an open window on the fourth floor.” – Al-Atma, 1972

Although François’ mental health would deteriorate immensely in the late ‘80s after he was stripped bare from the theatre he birthed, and following consecutive disappointments and abandonments from friends and lovers, these were ghosts that would follow him from years earlier, even maybe generationally, I had heard a grandfather of his would go out the same way, so François’ final leap, like Emile Ashrawi said with sorrow, “almost came 40 years late” and it’s true, Francois’ grand finale wasn’t a first attempt and El-Hakawati wasn’t his first theatre initiative either.

In 1972, François spoke the haunting line about fame and suicide on stage in the play Al-Atma (The Darkness), a play, like many of his, based on audience interaction with a lot of light switching and actors emerging from the crowd. It was the second play he directed and starred in for Balalin (The Balloons), an experimental theatre group he founded with the help of 40 artists, including Adel at-Tartir, Mustafa al-Kurd, Emile Ashrawi, and Vira Tamary. In 1973, the said troupe was cut in half, Balalin (Balloons) and Bala Lin (Without Leniency), and both ended two years later before In 1977, abu Salem would co-found Jerusalem’s El-Hakawati theatre group with Jackie Lubeck, his then-wife, to then turn it into a the theatre we know today with a $100,000 grant from Ford Foundation, the first of its kind from an international agency funding theatre in the “developing world”.

It is interesting to think that François’s life peaked twice. Once: constructing a theatre in Jerusalem, and once: a finale at a construction site in Ramallah. Although just a location inconsistency, this transition from Jerusalem to Ramallah is in itself a tip-off. A booming cultural scene in ‘80s Jerusalem to a mere urban sprawl in a ‘de facto capital’, the two, today, are set apart by checkpoints on checkpoints. Was his diagnosis one of cultural dysphoria and societal tragedy?

Like Palestinian rapper Shabjdeed would say recently in his song Krystal (2024): I’m one of god’s worst creations, sold a house in Jerusalem and moved to Ramallah

Little did François know that the same feeling that had him hop from the tenth floor is one that we all share, as creatives and intellects, and Palestinian creatives and intellects, only he is the only one with enough sanity and courage to act upon it, leaving us now to our long and humiliating intermission.

Little did François know that we have become unemployed fortune tellers, with no future to conceive. We are artists with no prophecies and no visions, and no prospects. We perform for donors, not for the people. We clap for mediocracy. Assimilated into NGO realism. The kind of realism François loathed. A culture of paperwork and deliverables. Of outcomes and delusional “impact.” Ghosts for mentors and tombstones for theatres.

We have become timid and hesitant and scared, we joke and tiptoe and sometimes get an obscure courage to be bold and loud, but mostly we tiptoe and deal. We make policed art and hope for someone to understand our cry for help. We play our hand and hope for some divine rescue. We are left with so little options today, we either jump from the tenth floor like François did, or until then, it seems we are acting in accordance and following closely the steps of an old Ethiopian proverb: “When the great lord passes, the peasants bow deeply and silently fart.”

![]()