Everything

People have embarked on pilgrimages as a means of shared worship for centuries, and on my first night in Australia’s Red Centre, I feel I’m an inadvertent believer. Dozens of people from the country over have come to this same sloping dune, descending on the art installation, Field of Light; kilometres of multi-coloured optic fibres installed at the base of Uluru for, at first, six months, then — due to its popularity — a year, and now, years to come. A travelling companion breaks the reverie, cynically commenting how perhaps Uluru is beautiful enough without human intervention (nothing the self-effacing artist hasn’t acknowledged himself); but it’s hard not to be taken by the hushed reverie that the scene inspires as the sun goes down. “I wanted to create an illuminated field of stems that, like the dormant seed in a dry desert, would burst into bloom at dusk with gentle rhythms of light under a blazing blanket of stars,” Bruce Munro writes on his online artist’s profile; and it’s a lovely mental image, these 50,000 optic lights representing buds pushing their way out of the seeds that encase them.

As the sun descends slowly, then all at once, luminescent colours dot the expanse of red sand before us. I’m reminded of my flight over from Sydney that same morning, when out of the window I see the desert drift in and out of unlikely shades of pink, brown and yellow, little whispers of clouds casting shadows onto the terrain. I was seated next to no one, and a stranger resided in the aisle seat, but still; I felt compelled to share the moment with someone, anyone (and sensed a few hundred faceless social media followers wasn’t what the occasion called for). “I’m sorry,” I started, and the man across the empty seat looked up from his laptop, before making a gesture to get up, probably thinking I needed the restroom. “But it’s quite beautiful outside right now, and I’ve never seen anything like it, and maybe you haven’t either?” So we looked and marvelled together, took our photos, and after this first of pilgrimages on this trip, went our separate ways.

I’ve never before been to the Northern Territory, never before looked upon this otherworldly monolith (our tour bus operator dares any Western Australians on our trip to say that their Burringurrah is the bigger rock formation, because “it absolutely is not.”). The only instances I’ve encountered Uluru were on the pages of Australian Geography textbooks, back when we unwisely called it Ayers Rock; and in Qantas commercials, and even then, always from the one side. It shouldn’t be possible for any of us to be here, really. It is the middle of the working week, and only a few years ago — and all the years preceding — there’d be an expectation for us to be sat at desks, where words and code, and memos and directives are written. But for a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, the ensuing move to remote working, and the words and the code (and the memos and directives) that built intelligent, adaptable laptops that allow for work anywhere, we wouldn’t be here.

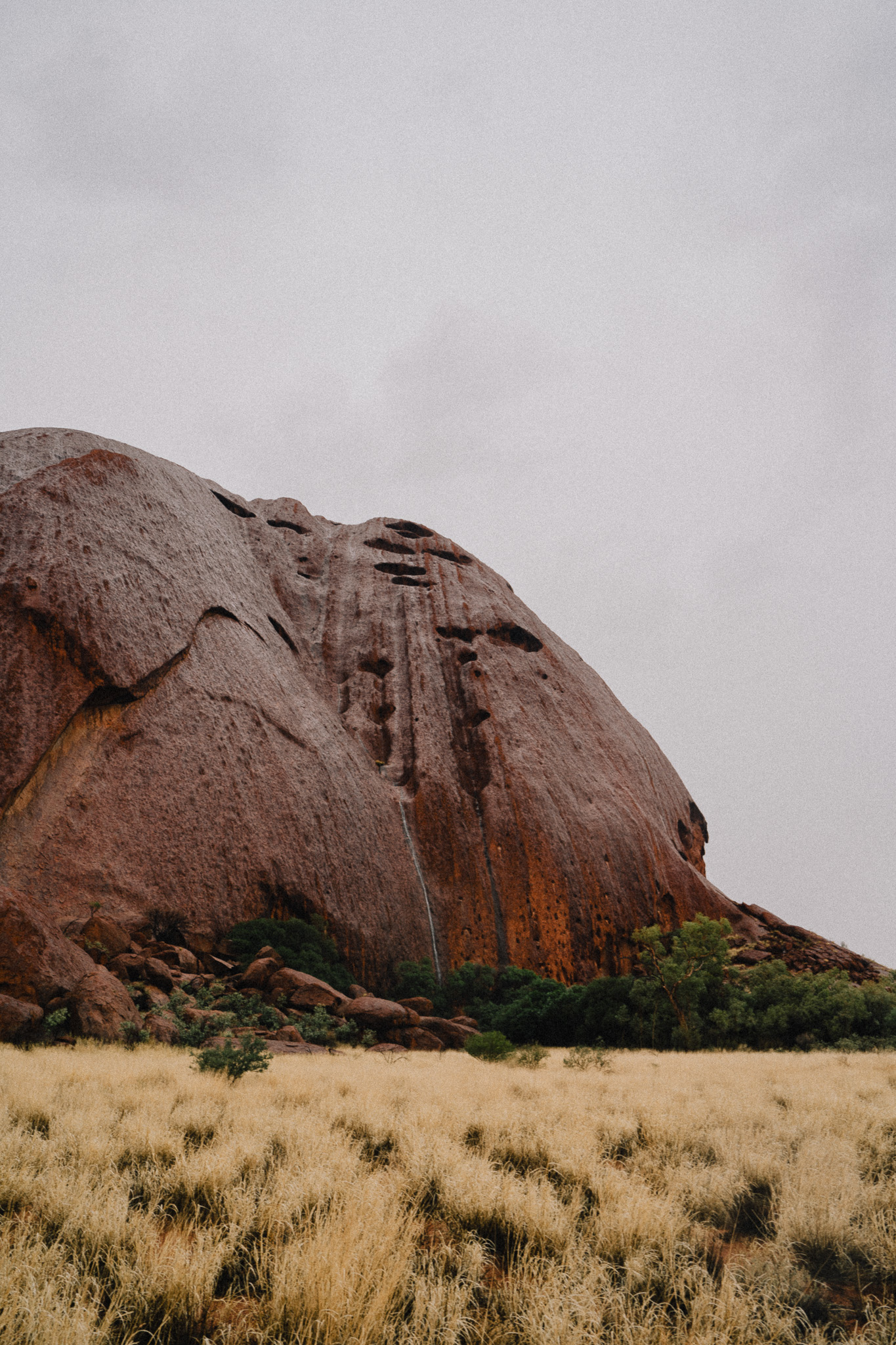

We’re advised there are few days of rain on Uluru, and that fall is most likely between November and March, so we’ve set on our walk in the same activewear we adorn for gym and the sidewalks around suburban homes. It is exactly one day shy of the third year anniversary when the chain link fence that brought tourists up its side was removed; and after walking the rock’s circumference, it’s clear that this is the only way Uluru was meant to be seen by visitors. Tjukurpa is the belief system— the traditional law, stories and spirituality — that guides the lives of the Anangu, the traditional custodians of this land. We spend the next few hours watching in our mind’s eye as our tour guide shares the tjukurpa that has been graciously shared by elders with him. In one story, Kuniya, an ancestral woma python whose rage and grief at her nephew’s murder by a group of venomous brown snakes, the Liru, caused her to strike at one of the assailants. Here, we can still see the two deep cracks where her blows fell on his head; there, we can see where the Liru’s shield, now a large boulder, lies where it fell. Kuniya, now a sinuous black line on the eastern wall, overlooks the battleground.

Since time immemorial though, pilgrimages and other ceremonies intended to transform have purified through discomfort, and it is no different now. First winds tug at our clothes and pull at our hair; then the rain starts. It doesn’t stop until we’re soaked through to our skin, and the red rock at our sides turns silver. Despite the cold, it is perhaps the closest any of us have come to awe in many years, if ever; it feels a deeply spiritual experience watching water fall down the sides of this thousands-year-old rock. We are pilgrims who’ve weathered distance and the elements to reach this moment of absolute and overwhelming gratitude. “If the desert is holy, it is because it is a forgotten place that allows us to remember the sacred,” writer and conservationist, Terry Tempest Williams, writes. “Perhaps that is why every pilgrimage to the desert is a pilgrimage to the self. There is no place to hide and so we are found.”

We reach Kulpi Mutitjulu, a shallow cave hours into our walk, and are sheltered from the rain for a short while. For many generations, Anangu families would camp here, at this cave, bringing with them the food they’d hunted and gathered, and share stories. The rock paintings used to illustrate those same stories are still there today; we’re shown the small grindstone slab on which the ochre clay was crushed, and on the rock face, the faded figures and lines damaged by early years of tourism (water was thrown onto the paintings, in an attempt to have them show up clearer in photographs).

“That, there, though,” our tour guide says, pointing at brighter concentric circle drawings to our right. “That’s acrylic paint, used in the last hundred years, when elders adapted to modern materials.” This was told to him by someone else, and he tells us in turn; and I’m only able to type this story — away from my desk, in the remotest part of the country — because of the words and the code (and the memos and directives) that built intelligent, adaptable laptops that allow for work anywhere, due to a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic. A moment as rare as seeing rain on Uluru in September.

This writer travelled courtesy of HP, whose new HP ENVY x360 2-in-1 Laptop makes it possible to create and collaborate from anywhere. From an instant file-sharing feature, HP QuickDrop to its tablet-to-laptop design, it’s the ideal device for creatives or professionals who want to work from anywhere. Discover more — including about its 20.5-hour battery life, Bang & Oulfsen audio and more — here.