Everything

“The only justice in this case is the street justice,” says Greg Kading, the former lead detective of the American federal taskforce who investigated the late ’90s murders of New York-bred rap artists Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. “No one will ever be held accountable. Both shooters have died in the same violent ways they killed their victims. The streets have kind of taken care of their own.”

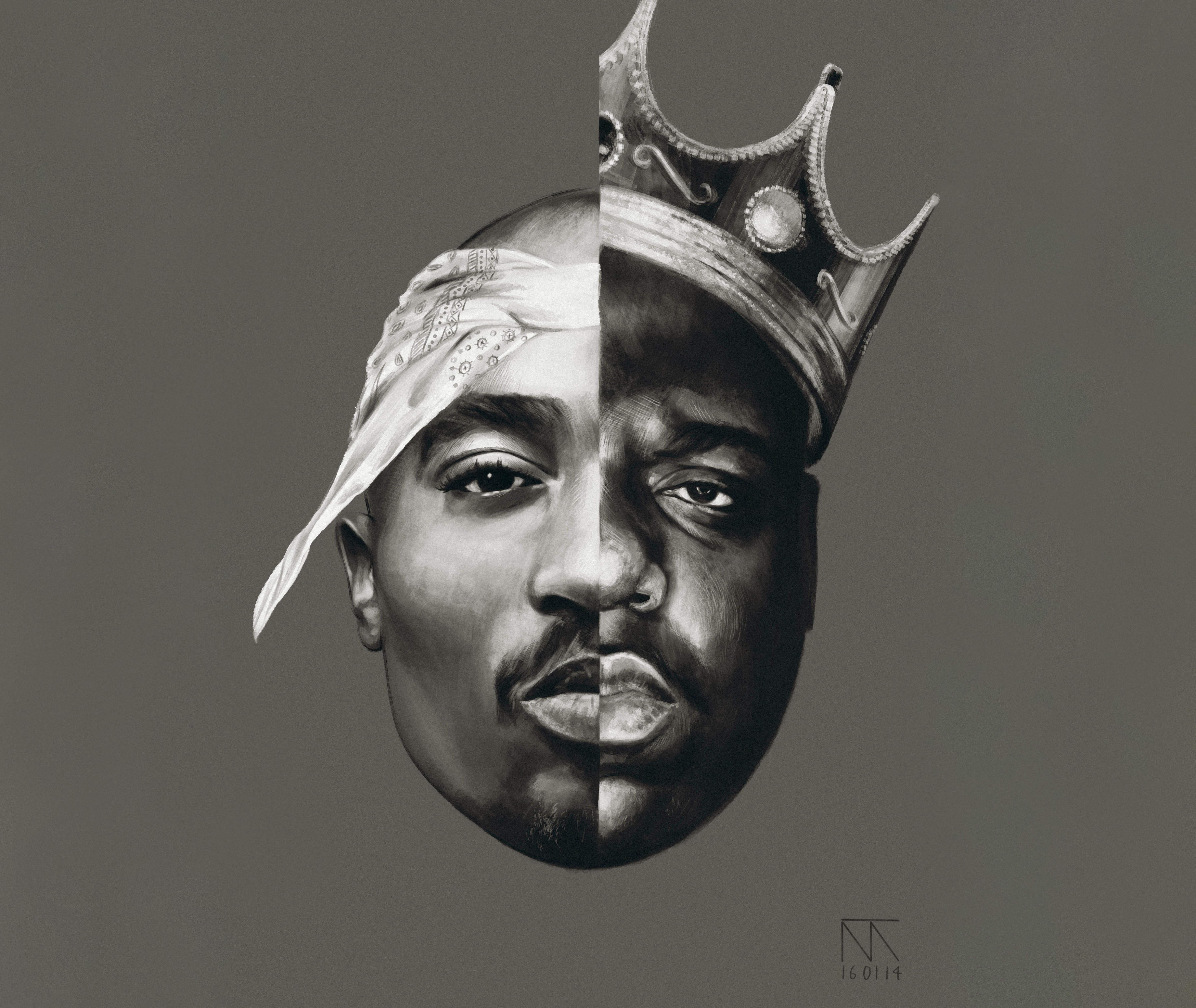

A six-month window between September 13 1996 and March 9 1997 is forever marred by the cruel extermination of the most influential rappers and lyricists of our time. To the average, milquetoast white guy, Biggie’s murder – the second of the two – was seen as just another Glock-bearing gangland killing; an echo of Tupac’s drive-by shooting in Las Vegas months prior and the result of the brutal and violent rivalry between those who bled blue (the Crips) and those who ran in red (the Bloods).

To fans, though, Biggie’s death hit harder than any comedown. His music was like CNN: a real and deft blend of firsthand accounts of misdeeds, the trappings of fame and fortune and the vices that numbed it all.

A decade after an initial investigation was steered maniacally by an impatient savant, LAPD detective Russell Poole, Kading – a veteran in gangs, narcotics and homicide investigations – was brought in to put to bed who shot Biggie on the Miracle Mile in Downtown LA that spring night in ’97. Three years later, Kading and his team had solved both cases by way of a recorded confession and an understanding of the basic street arithmetic that continues to nonsensically send black men to their graves. But making an arrest became complicated and ultimately not viable in the American judicial system.

For the then-46-year-old detective, this revelation was heartbreaking. “I remember sitting in my lieutenant’s office in 2009 and he said, ‘Greg, we’re going to put you on the bench for a minute.’ I understood exactly what that meant,” Kading remembers, breaking eye contact for the first time in our 38-minute chat, his shoulders drooping. “The LAPD weren’t going to pursue the case anymore. They knew that we had solved it. They were out from underneath this massive lawsuit and they were not going to waste any more time and energy on it. Tears started to well in my eyes and I just walked out of the office and went home. I’d been on the case for three years. I couldn’t accept it.

“Looking back, I think I could have argued more incessantly about keeping the case open and doing what needed to be done to get somebody prosecuted back in 2009,” he adds.

“You were defeated though,” I point out.

“I was,” Kading solemnly replies.

“Did you take your work home with you at night?”

“Yeah,” Kading admits, looking down. “It played a very real role in my personal relationships. If you really live your cases the way you need to, there’s just no real compromise. Relationships suffer and you sit at night wondering if that interview was as good as it could have been and ‘Were they lying to me?’ and ‘What should I do if they were lying to me?’ and ‘How do I outsmart them?’ It’s a big chess match.”

Just like little children were shot in the cross fire during impromptu street attacks, what people don’t think about is how this case consumed and deeply affected those who worked on solving it. Poole, for example, had a heart attack and died in a police station while desperately trying to resurrect his decades-old theory that dirty cops were behind the killings. Kading had to tell Biggie’s mother, Voletta Wallace, that no arrests would be made relating to the murder of her son, a moment the detective remembers by way of them both “just weeping and crying”.

Here, we sit down with Kading in ICON’s Sydney office to talk through the realities of gangland culture, Sean “Puffy” Combs’ alleged involvement, the ins and outs of why no arrests have been made and the very personal toll this case took on the detectives seeking justice beyond the code of the street.

ICON: What were the realities of gangland culture in Los Angeles in the late ’90s/early 2000s?

KADING: It was all-out warfare. I know in Australia you guys have motorcycle gang issues – which we have back in America on a large scale too – but these street gangs are a completely different environment and atmosphere. In motorcycle gangs, there are rules. In street gangs, there are no rules. It’s a green light on our enemies and when you see them, kill them. Live by the sword, die by the sword. The ’90s were completely out of control. The big problems were the Crips and the Bloods or the black gangs. Nowadays it’s the transnational or Hispanic gangs like MS-13. They’re operating on a whole different level. Crips and Bloods shoot and kill each other. These guys are into kidnapping, torturing, beheading and dismembering.

“In street gangs, there are no rules. It’s a green light on our enemies and when you see them, kill them. Live by the sword, die by the sword.”

ICON: Are there any stats that indicate the number of gang-related shootings that occurred during this time period?

KADING: Back in the early ’90s, LAPD was comprised of 18 different geographical divisions. I worked in one in South Central Los Angeles that was only seven square miles. Just within that area within one year in those mid-’90s, there were 140 gang-related murders. Multiply that by the number of divisions and you start to get into the thousands. It took a huge toll. Back then, about 60-70 per cent of those gang-related homicides went unsolved.

ICON: Because no one talks?

GK: It’s that gang culture of silence.

ICON: Tell me about the room with the hundreds of boxes of research and records that you encountered on your first day on the Biggie Smalls murder case. What did that feel like knowing you had to sift through it all?

KADING: It was daunting. It was the largest case file in the LAPD at the time – maybe even today. Coming into it, I didn’t have knowledge above and beyond the fact Biggie and Tupac were murdered rappers. The investigative work that had been made up until that point, led by Russell Poole, was daunting. I knew there was no way I was going to be able to wrap my head around it unless I took advantage of other people who knew both the African-American subculture and music genre.

ICON: Did you start from box one?

KADING: It was very systematic. We started at the time of the murder and we walked through the chronological timeline of the case. As you’re doing that though, you’re having to go back in history like, “Woah, I guess in 1994, Tupac was shot in a studio, did that have anything to do with Biggie’s murder?” and “In 1995, a guy gets killed in Atlanta who was a bodyguard for [Tupac’s manager] Suge Knight. Did that have anything to do with it?” As you’re moving forward, you’re always going backwards and revisiting events to find out if those had anything to do with the motive.

ICON: What was your first impression of Russell Poole and the work he’d done at that time?

KADING: In 2006, I thought he had a valid theory. I thought, “Wow, there’s some really compelling circumstantial evidence here” and we treated that theory with all the respect it deserved. But as we dug deeper and deeper into it, we could see what was happening. We could see that a lot of the information that he was depending upon was really unreliable, and as soon as the foundation of his theory was disrupted, then everything built on that theory crumbled.

ICON: You adopted a shotgun approach: Accept every theory as true and disprove it until you’re left with just one. Why are your findings more plausible than other theories?

KADING: We wanted to eliminate the theories that were ultimately baseless and weren’t relying on facts and evidence. Through a process of elimination, we were left with one workable theory and then we treated that as if it could be true and then all of the evidence began to support that theory. Then we got these confessions to support it. Once you have that level of testimonial evidence from people who were directly involved or corroborated, then you know you have solved the case.

ICON: Keefe D’s confession in Tupac’s death is protected against self-incrimination. But when it comes to murder, there shouldn’t be any statute of limitation. How, in 2019, are we sitting here with no arrests made and a full-blown confession outside the “immunity-for-information” interview Keefe D gave to police?

KADING: It gets a little bit complicated in a judicial setting. Outside of the interview he gave us, Keefe D has confessed to the same things on documentaries and YouTube channels. Those confessions are not protected. The problem is if you were to prosecute him in court, he’s the only living co-conspirator. The only witness against him is himself. He’s an ex-convict, convicted drug member and admitted gang member. His credibility immediately will become questionable and a jury or a judge is going to be left to decide, “Can I believe anything this guy has to say?” It just becomes a difficult prosecution because so much time has passed, so many key witnesses are dead and I don’t think any prosecutor is going to want to put him in court when we don’t have other people to corroborate what he’s saying in a meaningful way.

ICON: Is that why the Las Vegas District Attorney hasn’t arrested him?

KADING: I don’t know if the Las Vegas Police Department has put the case forward to the DA. That’s the big question: Why haven’t they? Because that’s their obligation and their responsibility and, at the very, very least, the LAPD and the LVPD should be saying, “We have solved these cases theoretically. We are going to take them off our books as unsolved. They are solved.” Now whether they’re prosecuted or not, that’s outside of our responsibility. It’s what we call “exigent circumstances” in American law.

ICON: Why wasn’t the theory of Puffy allegedly paying the Crips $1 million to murder Tupac and Suge Knight ever fully explored?

KADING: That’s a very important question to ask and answer with some real clarity and nuance. Puffy Combs was scared for his life. Suge Knight and his guys were definitely coming after him. Puffy knew that if he came to California, he was a marked man and, out of that desperation and fear, he associated himself with his Crip gang members because he knew that they could provide a level of protection that nobody else could. They’re from those streets, they recognised that threat before anybody else did. So he associated with those guys and realised he was a dead man walking if he didn’t do something about it. Out of desperation, Puffy was just like, “Whatever it takes to handle this problem, I’ll give you whatever, I want to live.” And so it’s that nuance that needs to be understood in relation to Puffy’s involvement. I don’t think he truly wanted to see anybody hurt, but he didn’t want to get hurt.

ICON: Were there any particular people of interest that you wanted to choke a confession out of?

KADING: Everybody, I guess [laughs]. For sure Puffy Combs. I have no respect for the fact that he can know what happened and be indirectly involved and watch the suffering of [Biggie’s mother] Voletta Wallace and know that his number one artist and supposed friend Biggie Smalls has been executed and do nothing about it. He never offered a reward that would lead to an arrest. In fact, he did the opposite. He told people not to cooperate with police. He knew that their cooperation would lead back to his association with the Crips who killed Tupac and we would have wanted to talk to him. Of course, he’s got a team of lawyers and they will filter every question and answer so you’re never going to get to sit down and have a proper investigation. He was a disappointment. I believe he lives with those skeletons in his closet.

ICON: What was it like telling Biggie’s mother, Voletta, that no arrests would be made in relation to the murder of her son?

KADING: That was probably the most emotionally devastating time – aside from the time I got taken off the case. We were both just sitting there weeping and crying about the reality of the situation. But, at the same time, there was another part that I think just made her even have more dissent and suspicion around the police department. Being face to face with her, I could see how victimised she was. She lost her son, she didn’t trust the police department, she spent a lot of time and energy trying to prove the police were involved in the murder and then found out it was all in vain. A lot of people were in her ear because they knew that if there was some settlement, they were going to get their big piece of that pie. I think she was taken advantage of in different ways and no mother of a slain child should have to be twice victimised.

ICON: What was Tupac’s mother, Afeni, like?

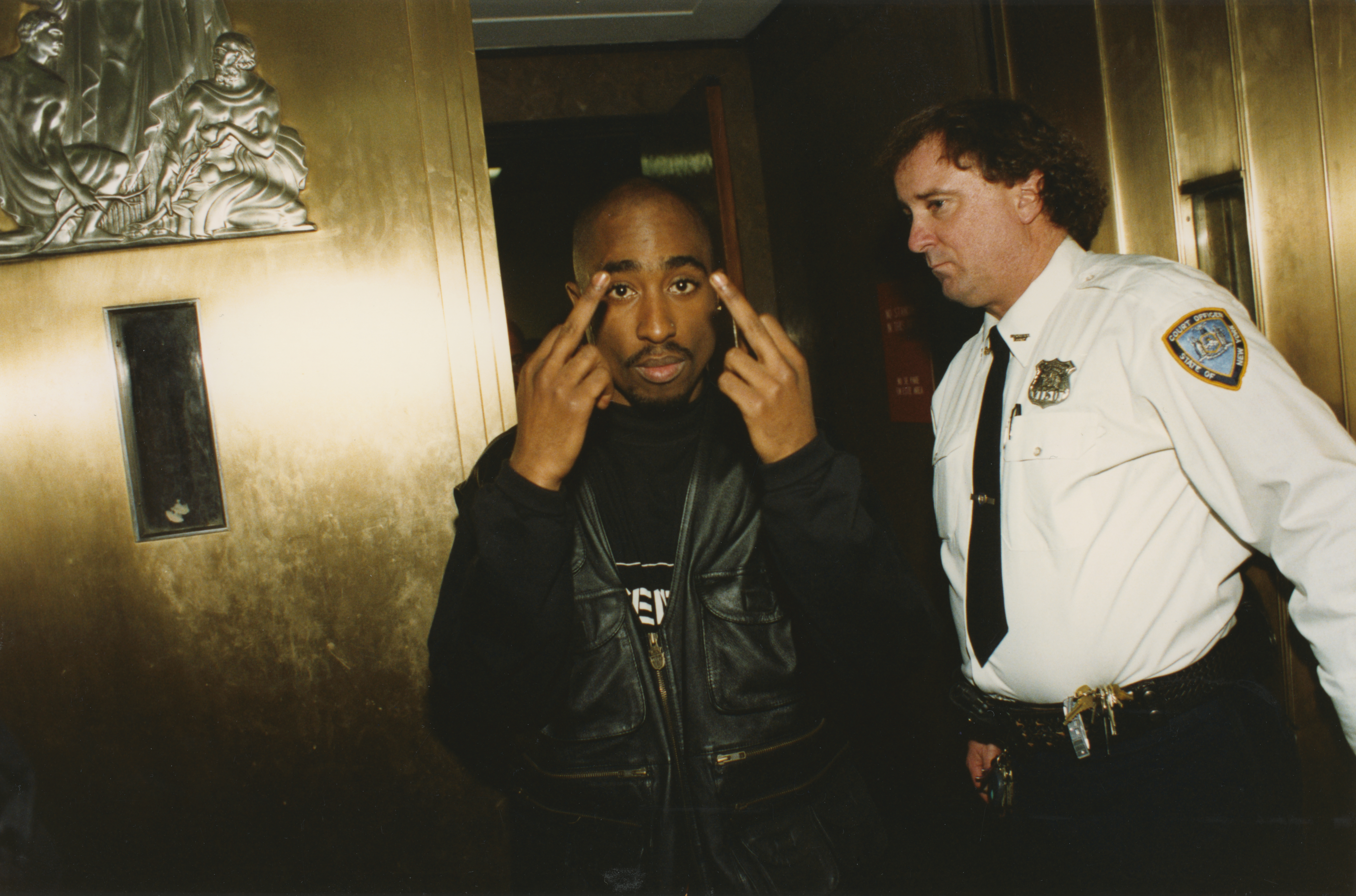

KADING: Afeni was a different animal altogether. She always knew who killed her son. There was never any doubt in her mind Orlando Anderson killed him, but unlike Voletta, she was not about the justice. For her, that was a dark, ugly moment in history that she doesn’t want anybody focusing on. She wants everything focused on her son’s music, his legacy, his person and all the positive aspects of who Tupac Shakur was.

ICON: The likes of Suge Knight and Tupac preferred to handle things on the street. Snitching was not the code they live by and they didn’t like cooperating with the police. How did you keep pushing forward when it seemed that every lead kept coming up blank?

KADING: I have a mild degree of OCD and, as a detective, you become somewhat obsessive with what you’re trying to accomplish. That drives you and I’m not going to let all my work be in vain. I think that had a little bit to do with it. The nature of my personality is that I’m not going to lose if I can do anything about it.

ICON: What was the most surprising thing you learnt about Biggie during your investigation?

KADING: I didn’t know getting into the case how close Biggie and Tupac actually were. After my meeting with Voletta, she was describing how Tupac would stay at their house and Biggie would stay at Tupac’s and she says, “They were the closest of friends.” That surprised me. All I knew about was the moment they became enemies after Tupac was shot in 1994 and thought Bad Boy Records and Biggie had something to do with it. I never knew Tupac was a mentor of Biggie’s. What’s worse than having a friendship break down and then be misunderstood and both of you get killed as a result because you never had that opportunity to just sit down and work it out?

ICON: Why do you think people are so fascinated by this case?

KADING: Conspiracy theories fascinate us. Nobody will ever fill Biggie and Tupac’s shoes and what they brought to that music culture. It’s also very difficult to just settle with the fact that these guys were wiped out at such a young age – they hadn’t even really reached their prime – and nothing’s been done about it.

ICON: How do you see Russell Poole now?

KADING: His heart was in the right place. I think he really truly, genuinely wanted to solve the case and get the answers. His problem was that he had lost his objectivity. He wanted his theory to be true and, in his pursuit of proving that theory, he took only the information that was supporting it and discarded the information that refuted it. As an investigator, you can’t want a certain outcome other than what is true. He was having a whole bunch of problems in his personal life: He was a heavy drinker, he was involved in an affair, he got in trouble at work, his brother went missing. And then he had all this compelling circumstantial evidence about these cops that were supposedly moonlighting and were a cause of concern for him. It was just a bad storm of ingredients that led to him spiralling down a rabbit hole.

ICON: Did you find his death in 2015 suspicious?

KADING: No, not at all. Years and years had gone by, he was very unhealthy and stressed out. He walked into the police station that day hoping to get some resurrected opportunity in life and the guys that he was talking to were like, “Give it up.” His heart seized. He just had a heart attack.

ICON: You were given a front seat to gangland killings – some in broad daylight and most senseless. What’s your opinion on America’s gun laws?

KADING: It’s a really complicated situation because I respect we have a constitutional right to bear arms. America’s a different culture. It’s very hard to say, “Australia doesn’t have guns and they don’t have the kind of violence we do so it must be because people have guns.” It’s not. We have a different morality. We don’t have the same type of respect people [in Australia] seem to have for one another. It’s a cultural thing. Criminals are always going to get their hands on guns; it’s the criminals who are committing the violence. Then, of course, there’s this mental health issue that we have where mental health victims are getting their hands on a gun. Much is being done about it, by the way. For us to change our constitution and to eliminate guns as a right, we are no longer the Americans we have grown to be. If we change that part of our constitution and say, “OK, you no longer have rights to guns,” well, what about rights to free speech that we’re guaranteed? What about rights to unlawful search and seizure? Can the cops just come into our house now? When does that slippery slope stop once we start fucking with our constitution?

What REALLY happened on the nights of the murders?

Riding the front passenger seat of a BMW along the Las Vegas strip on September 13, 1996, Tupac was fatally shot by prime suspect Orlando Anderson, a young Southside Crip the rapper and his Death Row Records kingpin manager, Marion “Suge” Knight, had got into a fight with earlier that evening. Six months later, Tupac’s friend-come-foe and platinum-selling rapper Biggie – real name Christopher Wallace – left a crowded party in Downtown Los Angeles and was sitting in a sport utility vehicle when alleged gunman Wardell “Poochie” Fouse (an associate of Knight) sped up next to Biggie and began spitting gun fire. The 24-year-old was pronounced dead at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center on March 9, 1997. Under his producer at Bad Boy Records, Sean “Puffy” Combs, Biggie was just about to release his huge double album Life After Death on March 25. In 2009, Kading set up a drug deal sting to coerce Anderson’s uncle, Duane Keith “Keefe D” Davis, into talking about Biggie’s murder. The trap worked, but since Keefe D only exchanged the information for immunity and the shooters and co-conspirators were all dead, no arrests have ever been made. “Biggie’s murder was a result of a retaliation on Tupac,” explains Kading. “Suge Knight – a fierce rival of Puffy’s – ordered the hit.” In June 2019, Fulton Street in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, New York City – where Biggie grew up – was renamed Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace Way. Street justice? Maybe.

Kading authored the 2011 book Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls & Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations. True-crime drama series Unsolved: The Murders of Tupac and the Notorious B.I.G is now streaming on Netflix and stars Josh Duhamel as Kading.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE OCTOBER 2019 EDITION OF ICON AUSTRALIA.

RECEIVE YOUR ISSUE HERE.