Everything

Times of political turmoil have always spawned seminal works of art. Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica”, Roberto Rossellini’s “Rome: Open City” being famous recollections. Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster Series was a commentary on the media’s increasing coverage of violence and the subsequent desensitisation of the public. Although there are some artists who insist that their work is not political, their claims ignore the stakes of representation; for any artist to deny that their actions have political implications is to deny the fact that media and entertainment shape the way that people view the world and everyone inhabiting it. These days, delivered by a deeply divisive algorithm people don’t share policy papers, they share things that move them. For Eugène Delacroix, it was “Liberty Leading the People”. For pop culture expressionist, 3D artist and real-time commentator, Mike Winkelmann, it’s a daily deadline that’s leading his moniker, Beeple.

![]()

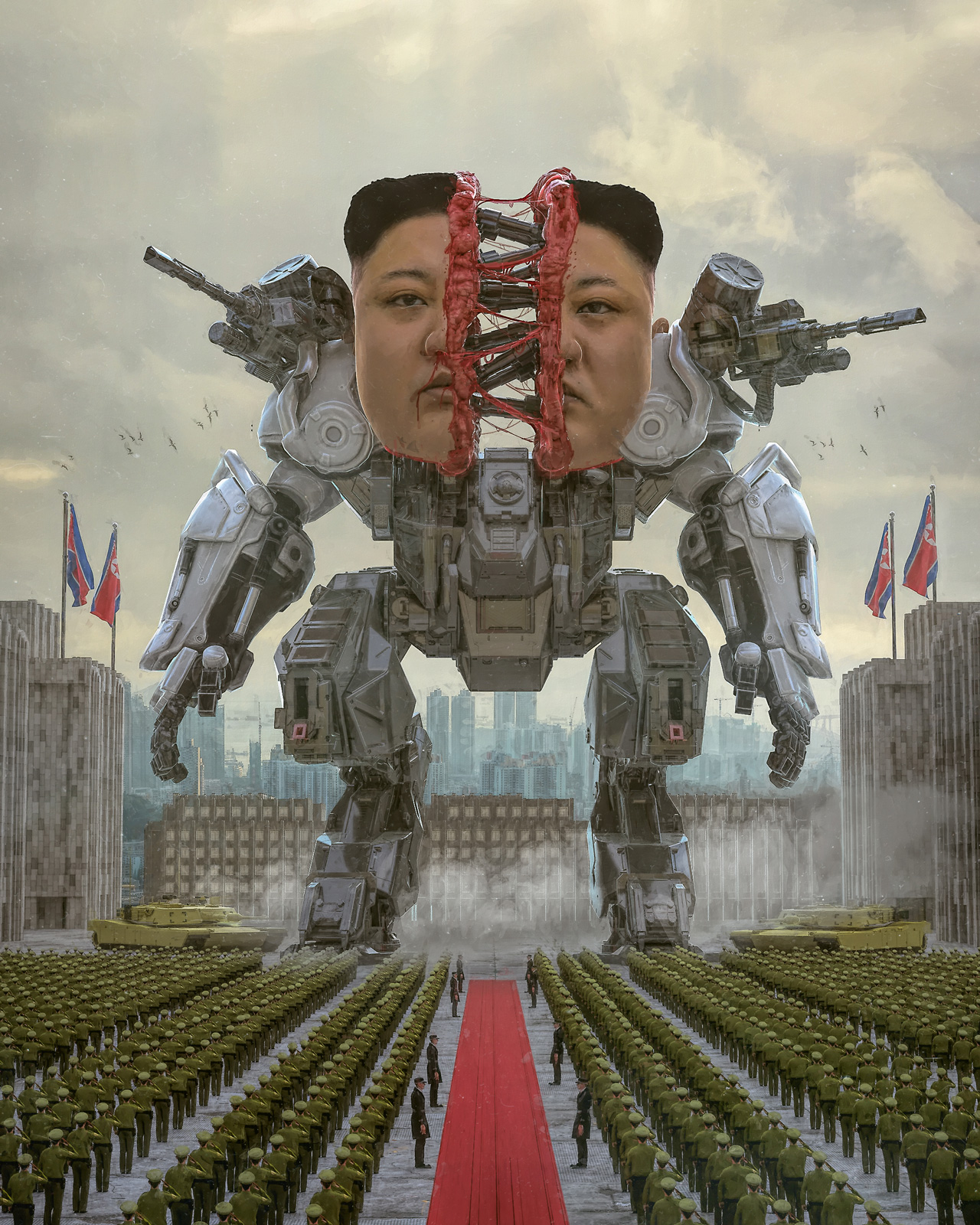

‘It’s going to get super fucking weird’ proclaims Beeple when I ask him where he thinks life is going. What could be weirder than a Cyborg Trump breastfeeding Biden controlled by Zuckerberg whilst the American Eagle Drops hamburgers on a crumbling TikTok Logo with Clinton laughing uncontrollably in the background? I think to myself. “Nobody is in control of this, and nobody knows where it’s going. If anybody does, they’re lying. We just don’t know. Nobody does.”

There are those who claim to have clarity in their cause. Unobstructed, their methods and journey are set. And as we enter the final days of the United States 2020 Presidential election, we might like to think of politics as a rational business, where sensible people logically discuss and debate the issues at hand, come to a reasoned decision, and then judiciously act. The way forward however, couldn’t be murkier. As recent developments in cognitive science suggest, humans just don’t think or behave this way: we make sense of our world through stories and symbols that frame the information we receive, then act accordingly. The principles governing civic action are more likely to be found in the worlds of popular culture and entertainment, and artistic expression and reception, than in textbooks of political science.

“I watch a lot of news,” says Beeple. I note two humungous television screens in the background of our Zoom call. “One of them is set to Fox News and one of them is set to CNN. They’re on all day.” For Beeple this is business, unusual. “I feel like a lot of the work that I do explores different dynamics and tensions between people who have massive amounts of power, especially as it relates to money or politics. Even somebody like Mark Zuckerberg, who has the capacity to say ‘Okay, we’re going to boot Holocaust deniers off the internet’ like I just saw immediately a whole chapter gets erased. He could just come out and be like, ‘Okay, I don’t want to see any shit with GMOs on the platform,’ then all of a sudden that’s just gone too”.

Acknowledging that the political landscape is also a cultural one opens up greater social understanding. Whereas art was previously limited to museums and galleries, and activism to street demonstrations and state houses, artistic activism is at home anywhere you look. “You can really have your pick of what you want to ingest”, says Beeple. “There’s just so much media out there that if you’re not trying to do something that’s clearly different, clearly better, then you’re just going to get lost in the noise.” I bring up the marketing machine that is the Republican party. “Trump has a certain kind of charisma, really. It’s very simple and easy to understand. He literally talks at a fucking six-year-old level and has done an incredible job at convincing a lot of people that Biden is six seconds warmed up from death,” Beeple qualifies.

Such real-time communication, neither overtly “arty” or “political” is more familiar and safer to an audience than a museum or a rally, and thus makes artistic activism as a response more attractive, approachable, and friendly than traditional art or activist practices. Artistic activism – as an effective image, performance, or experience – is well suited to artists in the age of social connectivity and disbursement.

“I’ve never felt remotely possessive of my designs. It’s less ‘that’s my thing’ and more its own thing. Where it goes and where it finds itself, that’s none of my business.” For the last 13 years, Beeple has been putting out multimedia works every day in a project he calls Everydays. By being on constant deadline he cannot pore over the work, or be overly analytical in his message. “Putting them in hyper, real-time commentary is really only something I started doing in about the last year. I almost look at it like a political cartoon, but instead of just a sketch, it’s a political cartoon with the most advanced digital tools. I’m trying to say something with these, but I don’t have a super clear message that I’m trying to get across. Sometimes I do, but most of the time I’m trying to make art.”

Throughout history the most effective civic actors have married the arts with social campaigns for change, using aesthetic approaches to provide a critical perspective and imagine the world as it could be. In the struggle for Civil Rights for African Americans in the US, for example, activists drew upon the stories, songs and participatory culture of black churches, staged media-savvy stunts like Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus, played white racist reaction against peaceful protesters as a sympathetic passion play during the campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama, and, most famously, used imaginative imagery in a speech to call America to task for its racist past and articulate a dream of a better future. While Martin Luther King Jr. is now largely remembered for his example of moral courage, social movement historian Doug McAdam’s estimation of King’s “genius for strategic dramaturgy,” likely better explains the success of his campaigns. Even Jesus’ use of parable to engage his audience was a working artfulness to make activism effective. And while many activists know this intuitively and coordinate their expression deliberately, artistic activism is best suited for the contemporary moment, and shows up in unlikely places and often has unintentional results.

“I’m not extreme in my political views”, Beeple asserts. “To me, it’s very frustrating that we have such binary parties these days, because I’m very much in the middle.”

“I voted for fucking Bush twice, which seems dumb in retrospect. I’m not sure liberal but it’s just crazy town on that other side.”

“Politics is a big source of inspiration for my works, and I’m a big news junkie so that’s probably why there’s so much political persuasion in my works,” he continues. In terms of his activist intentions, Beeple has no pre-conceived plan but rather “uses a computer and shitloads of assets and 3D rendering software, to comment on something hours after it happened in the most technically advanced way, without too much additional thought. It always comes from a funny place, and I try to approach these topics with humour so they are relatable”.

“People get in these little bubbles, and I feel like they get fed the same fucking thing” Beeple asserts. Whereas traditional forms of protest, like marches, need to constantly increase in size or scope, or like in recent times descend into violence to become newsworthy, the creative innovation at the heart of artistic activism provides something uncommon, or out of place, that can attract attention and become memorable. “My next door neighbour was stationed in Bahrain recently, and she had one of her colleagues share one of my works with her without realising we lived right next door to one another. To me, that stuff is way more valuable, because at the end of the day, I’m making artwork and releasing it online for people to see, digest and share. Before I started the Everydays, I did a lot of short films. I would pay hundreds of dollars to these film festivals to get them to show my work. Okay, now I can just release it and don’t have to pay anybody!”

Social networks work as an access point through which organisers can approach and engage people who are otherwise alienated by institutional systems like voting, lobbying, political campaigning, and legislation. Unlike fine arts or political policy, artistic activism takes no specialised knowledge for an audience to “get it.” And, as an art form, artistic activism is always open to multiple meanings and, thus, multiple ways for the audience to connect, but the delivery methods are not without their issues: “I think there’s a few things with the algorithm that push people to be a little bit more radicalised and lean in to unhealthy thoughts,” Beeple ponders. “But conversely, [social media] is blamed for a lot of things.”

“It’s impossible to police all this shit because Facebook and Instagram are basically the internet now.”

“In some way it was inevitable. This is the next evolution of the internet, and it was always going to happen. As an artist, I really try to make a concentrated effort to limit how much feedback I’m getting from these social media machines. I don’t look and see how many Likes it’s getting each day. I don’t really want to read all the comments people are writing down below. But to be quite honest, I think at the end of the day these are just machine algorithms deciding what should be shown to whom. It’s just literally what people are engaging with the most. I think it’s no more than that.”

Beeple’s artistic approach is a school of blue-sky brainstorming, quick sketches, multiple iterations, rapid prototyping, and a spirit of play — as well as risk, and the acceptance of failure. Approached as a creative process, he is more apt to see multiple solutions to problems he may experience in his creative process. Free to experiment, he often identifies the answers to problems he didn’t set out to solve, end-running the commonplace framing of political commentary to open up new possibilities for public interpretation.

“I think things have become so granular, but at the same time there’s so much information out there”, Beeple says. “It’s just a fucking fire hose, and if you’re trying to make sense of it it’s really hard when shitty information can get through. Especially when those crazy, batshit things act like they’re going to help explain the rest of the craziness around us right now”.

Caring about the world in its entirety is a tough task to participate in. We open our eyes to things other people do their best to ignore, and constantly fight against forces greater than us: systemic prejudices, entrenched institutions, well-funded opposition. As an activist it would be easy for Beeple to get burnt as his works increasingly become defined by certain algorithms to certain people. As an artist, it’s easy for him to get frustrated that the creative work he does has unmeasured impact on the issues our society cares about so deeply.

“It’s definitely going to get more complex. It’s going to get faster and faster. I don’t know what the next 30, let alone 50 years is going to look like, because I feel like there’s so many different things. What will our priorities be? Who knows. Technology is changing things faster and faster, and changing people’s brains, right down to how their brains work.

“Think about the time between huge inventions. Previously 200 years could go by and it’s like ‘Whoa, what did we invent this century?’ ‘One thing’. This year alone we probably had like 700.”

Creating and sustaining lasting change demands a switch in values, beliefs and patterns of behaviour – actual and meaningful cultural change. While changing laws and policies are essential, rules will not be followed nor policies enacted unless people have internalised the values that lie behind them. And while marches, rallies and protests are important, they won’t have lasting impact unless the issues resonate with all people. Culture lays the foundation for politics. It outlines the contours of our very notions of what is desirable and undesirable, possible and impossible. “Despite some of the references in my artworks, I don’t think the world is going to turn into this dystopia”, Beeple reassures me. “I’m not making commentary like ‘It’s going to be a fucking dystopian nightmare where we’re all just eating mud under a bridge’ or whatever.”

As Beeple considers today’s Everyday he draws his inspiration from culture, to create culture, without fully realising it. His visions are useful for setting pragmatic goals and concrete objectives and provide a loadstone to orient our direction, so we don’t get lost – outlining the very purpose of participation in articulating what is normal, possible, or even conceivable in our world ahead.

Words: Marne Schwartz

Art: Mike Winkelmann aka Beeple