Everything

The footage of Barack Obama virtually propped up in between Lakers Royalty – and male mountains – Shaquille O’Neal and James Worthy at Game 1 of the NBA finals this year is one for the record books. The former US President appeared courtside as a virtual fan during the first quarter of the match between the Los Angeles Lakers and Miami Heat.

“Oh hey, what’s up Prez?”

“Oh hey, what’s up Prez?” the legend-turned-broadcaster O’Neal quipped as if he really were physically sat next to Obama. (If this were true, he would have knocked the politician out with an elbow and his Hall Of Fame ring.)

Come global lockdowns, the NBA were hell bent on putting their best sneaker forward to bring the live action to the viewer stuck at home – and shifted into gear at a speed that would rival a LeBron James tomahawk dunk. They built a bubble at the Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando Florida and figured, as long as they could get all players, coaches and team personnel packed into one place — with COVID-19 testing assuring that none had been infected with the virus — and not let any non-essential people in, they could preserve the NBA season.

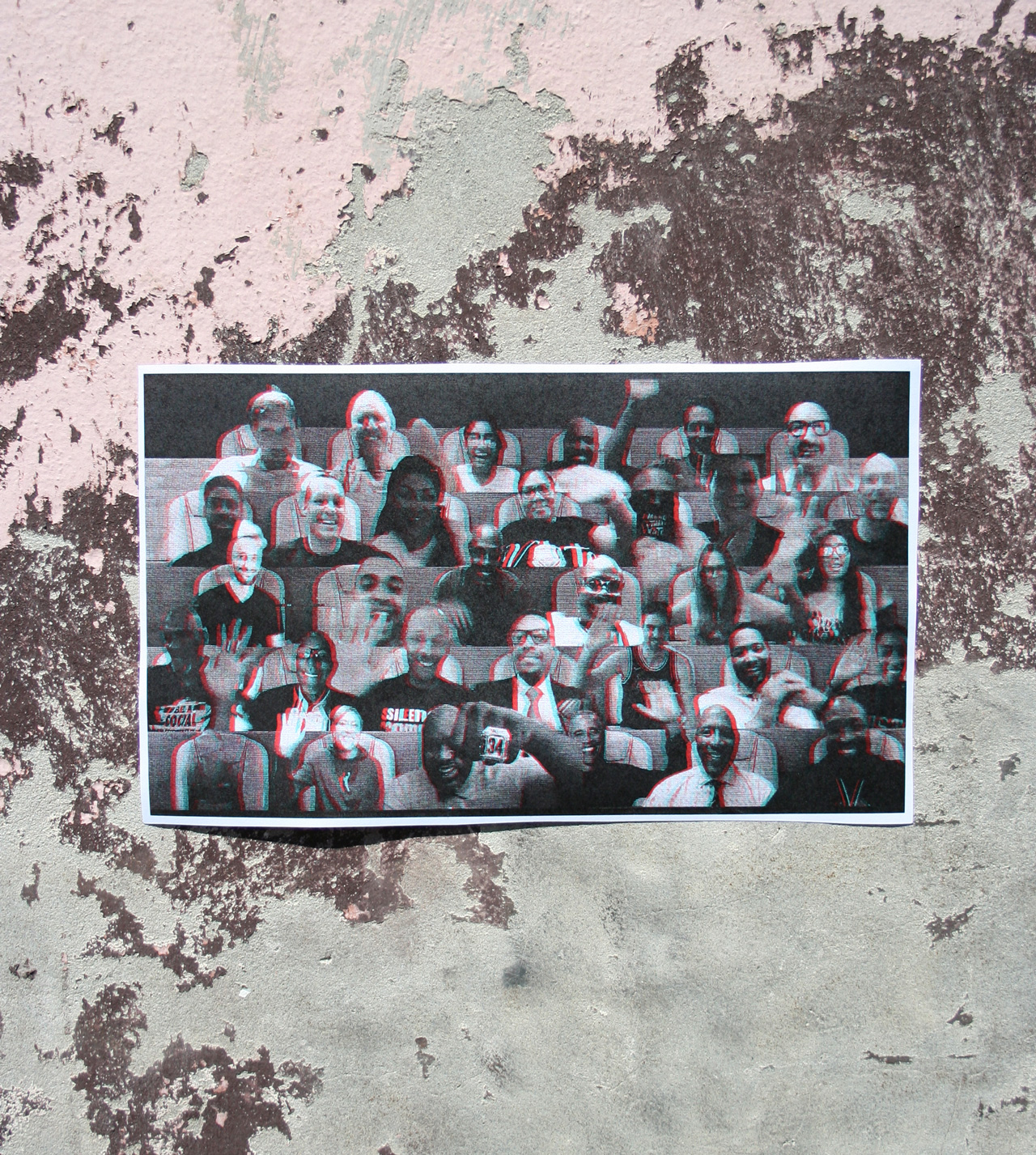

Then, with the help of game partner Microsoft, the NBA rebuilt the fan experience with one goal: to increase the community feel and connection between fans in a crowd-less arena. Using 17-foot video boards that made use of Microsoft’s Teams Together mode, 320 fans, like Obama, were able to use their Webcams and smartphones to cheer on their favourite teams. “We landed on 320 because it was the best visual experience as the fans aren’t too big or too small,” says Sara Zuckert head of Next Gen Telecasts at the NBA. “We have hype teams now and fans are participating in activities like the wave.” Zuckert was also behind the Virtual Cheer function on the NBA app, NBA.com and Twitter where fans could tap a team logo and it would fire off cheering in the Orlando arena. “It lets the players see engagement at home and is another element to bring the community closer together,” she says.

As there were no fans allowed courtside, the NBA worked with American cable sports channel ESPN to create a “railcam system” which offered viewers at home alternative vantage points. “[It] brings to life the incredible athleticism of the NBA game and provides unique access and angles that we’ve always wanted to be part of our coverage,” says Tim Corrigan, senior coordinating producer of NBA broadcasts at ESPN.

But in order for broadcasters to be able to bring the armchair viewer into the live action in this way, they had to be able to not only think up and invent these technologies, but be able to deliver them all together in live time.

Consequentially, broadcast control rooms forever changed as sports producers were thrust into the role of movie-makers. Here’s how ESPN in the US and the Seven Network in Australia used sound to transport the fans courtside – and how the pandemic has forever altered the way we watch sport.

Capturing The Body-On-Body, Boot-On-Ball

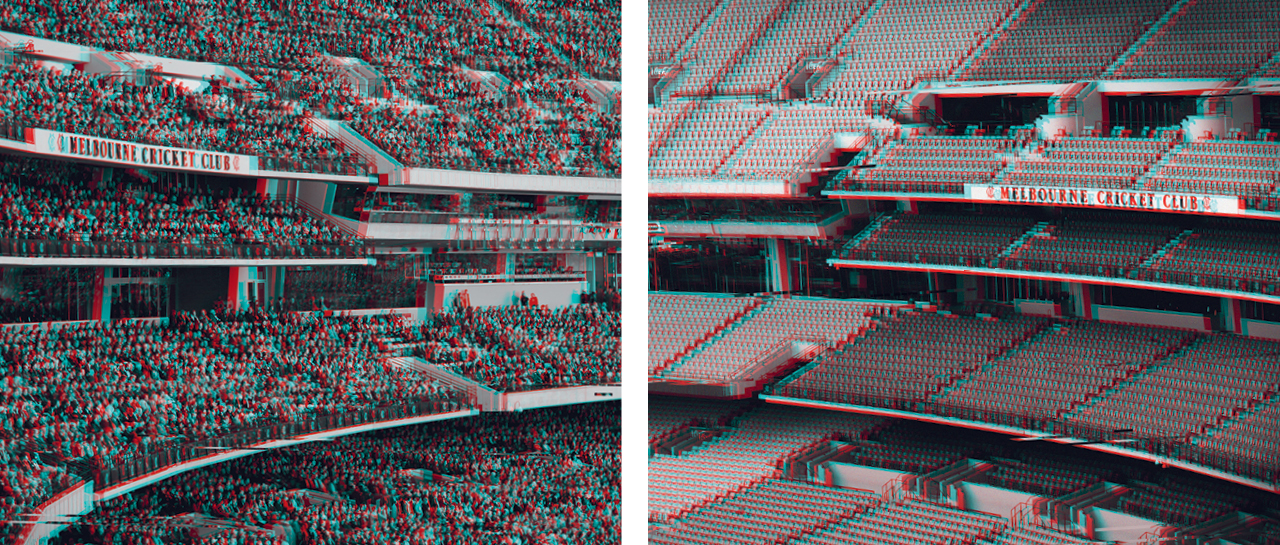

The Managing Director of Seven Melbourne in Australia and Head of Network Sport Lewis Martin remembers standing on the boundary line of an AFL field in one of the first crowd-less games in March. “I’ve never had that experience, it’s chaotic out there, very intense,” Martin says. “The screaming, the yelling, the movement, the coaching, the calling, the body-on-body. When a player marks the ball, the ball slaps into their hands. When they kick it, it’s a big oomph. It’s quite remarkable.”

The mission was huge. How would Martin transport his viewer to this moment? How would he get the fan to the boundary line? How would they experience this feeling? “They say to never waste a crisis – and innovation comes from necessity,” says Martin. “My team would conduct what we’d call Apollo 13 sessions where we would literally start from scratch. We’d ask, ‘What have we got to rebuild this broadcast?’ We didn’t talk about limitations and we’d always go back to the scene from the film Apollo 13 where they got all the junk that was in the capsule and dumped it on the table. That’s effectively what we did as a broadcast operation. Then we’d look at what we had to play with and where we’d apply it.”

They say when one human sense is lost – be it sight, sound, smell, touch or taste – the areas of the brain usually devoted to handling that sensory information are rewired to strengthen another. With this in mind – and in the absence of fans being able to attend footy matches – Martin and his team were tasked with capturing a soundscape that would draw the viewer into the action from their lounge rooms.

“If you’ve got two teams or two competitors, the third cast member is always the fans, each and every time,” says Martin.

“We started out by looking at a whole range of audio effects. We needed to get it right, we needed to make sure that it wasn’t distracting or overbearing. We wanted these sounds to be familiar and comforting and sort of like a backing track. The game is King, right? And we needed to make sure that the fans were talking about the game and not the sound effects the next day.”

Home Versus Away

The sound of a goal being kicked by a Hawks’ player at a Hawks’ ground will sound different to a goal being kicked by Carlton during the same match. As such, the sounds of fans at different clubs and at different venues were captured separately and an engineer and game expert would sit in the control room and “ride the sound” on an iPad in live time. This person’s role would be to insert the cheers, jeers, gasps and boos – but getting it just right wasn’t always easy.

“We had audio operators managing the volume in and out of the crowd depending on what was happening on the field. They were very responsible people,” says Martin. “I call it the Goldilocks effect. You can’t have it too hot or too cold, it’s got to be just right. Sure, there were instances where we thought, ‘Oh that’s a bit rich’ but by and large, they got it right. The practise really brought the operators into the game. They were almost like DJs.” Practising on a few games prior, Martin said he and his team would test the audio by listening to it with their eyes closed because “you hear everything differently without vision”.

Practise Makes Perfect

But with 85 percent of the Seven Network’s AFL broadcasting skillsets stuck in stage four lockdown in Melbourne, sacrifices needed to be made. Martin says he had guys quarantining in all parts of the country – and away from their families – so he could facilitate games all over Australia.

“If there was a sweet spot for COVID to absolutely annihilate the live sports broadcast teams, it was Melbourne,” says Martin. “Changes needed to be made very quickly and people needed to adjust.”

Some of Australia’s best broadcasters were in their respective home states as games played out across borders. “The tech was really important, we had a number of screens available to [commentator] Bruce McAvaney in Adelaide so he could call the games with [fellow commentator] Brian Taylor who was elsewhere,” explains Martin. “We had to minimise the delay between Bruce and Brian so they could call together.” “We had a rehearsal the night before the first game and that was so important because it enabled us to check the tech,” Martin adds. “Because the audio was so sharp and crisp, the callers felt like they were really close despite being in different states.”

Inside The Truck

As we go to print, the NFL in the US are moving games around the calendar to accommodate for players being struck down with COVID-19. Like the NBA, the NFL looked at the option of playing the season out in an enormous bubble but ultimately felt that this wasn’t practical, and accepted the fact the code would function at the mercy of the virus. At time of publish, the Titans now have 16 personnel infected including eight players. Their recent match against the Steelers was pushed back and then ultimately postponed. Cam Newton, the Patriots star quarterback, has also just tested positive.

For broadcasters, it’s a test in logistics, organisation and adaptability – and the health and safety of everyone, including the television teams, is paramount. As Senior Coordinating Producer Steve Ackels at ESPN tells ICON, COVID meant the actual atmosphere inside the NFL control rooms changed overnight. “We’re minimising in-person interaction, and we’re social distancing in the production trucks,” says Ackels. “Instead of getting everyone together in a conference room, we conduct our pre-game meetings over Zoom. When the live game is happening, the trucks are a lot quieter than normal and much less crowded. We’re wearing masks. The one thing that hasn’t changed though is the passion and pride we take in documenting the game and presenting Monday Night Football [in the US].”

Opening Night

When the first crowd-less AFL match rolled around – and it was time to test the innovations – Martin admits to being really nervous. “It was exhilarating. I’ll never forget it,” he says. “We were doing things that had never been done before. We’re really appreciative to have jobs and the team literally worked seven days a week with a great deal of passion in order to get this season done. I can’t tell you how much they’ve inspired me. It’s been a remarkable year.”

“We are creating the ultimate reality television,” he adds. “We’re there to tell the story.”

Looking To The Future/ Looking To The World

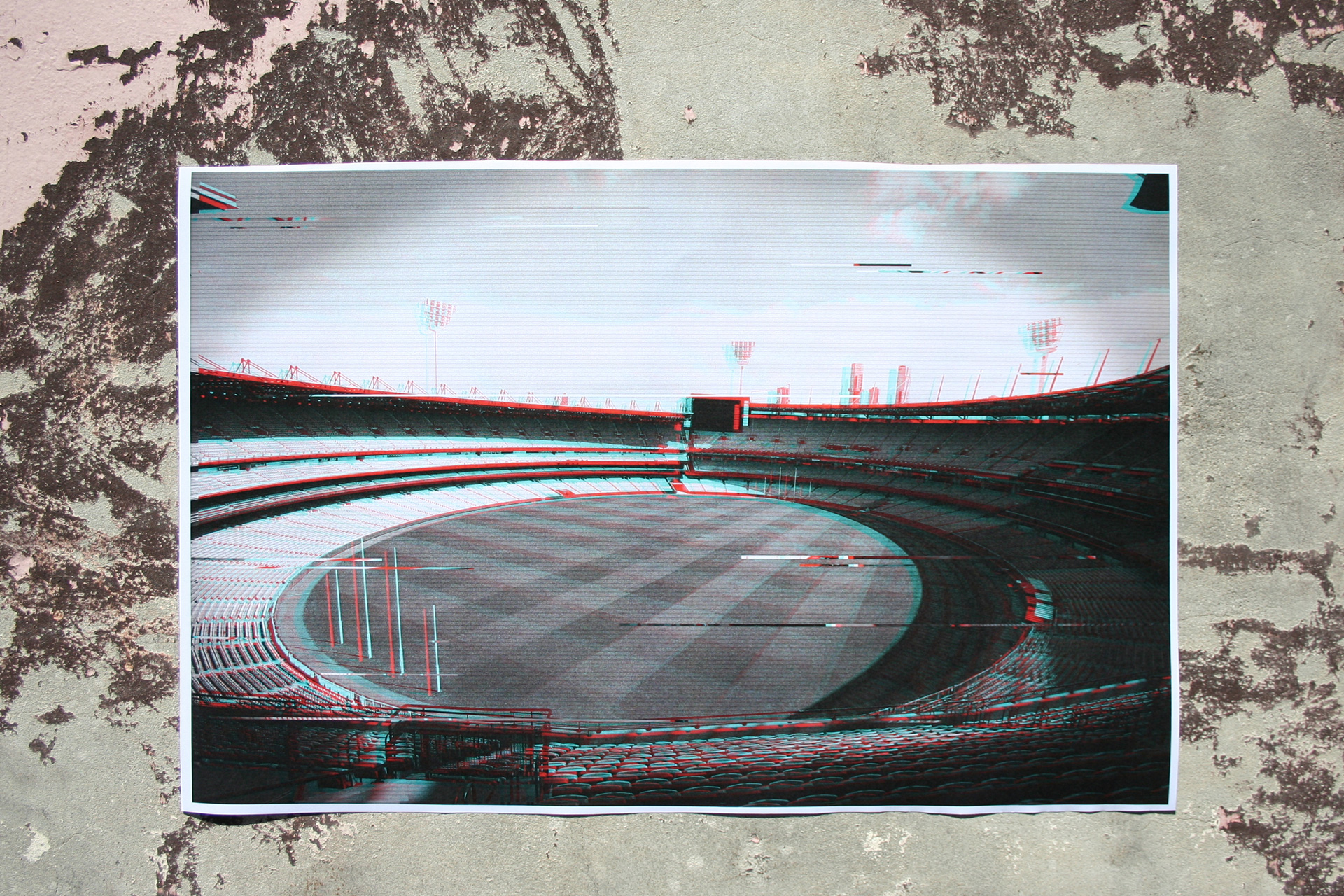

But what will spectatorship look like in the future? Will these new technologies be taken into games hereafter as crowds return? “There’ll be some keepers and there’ll be some things that’ll go onto the shelf that we’ll look at,” Martin says.

“We’ve got colleagues in Europe and the States that are constantly searching for vision and inspiration. But AFL is the largest playing field in the world of sport,” he explains. “It’s 360 degrees in the sense that the ball goes in all directions – and [compared to a basketball court], the stadiums are massive, it’s not a square box. We look at the innovations that are happening in different codes and then we look at the AFL. We should all be proud of the task of broadcasting AFL because there is no game played in such a large outdoor arena with a ball travelling 360 degrees.”

“But I’m waiting on the day for crowds to return at capacity. Nothing beats it,” he adds. “That’s when those stadiums sing.”