Everything

![]()

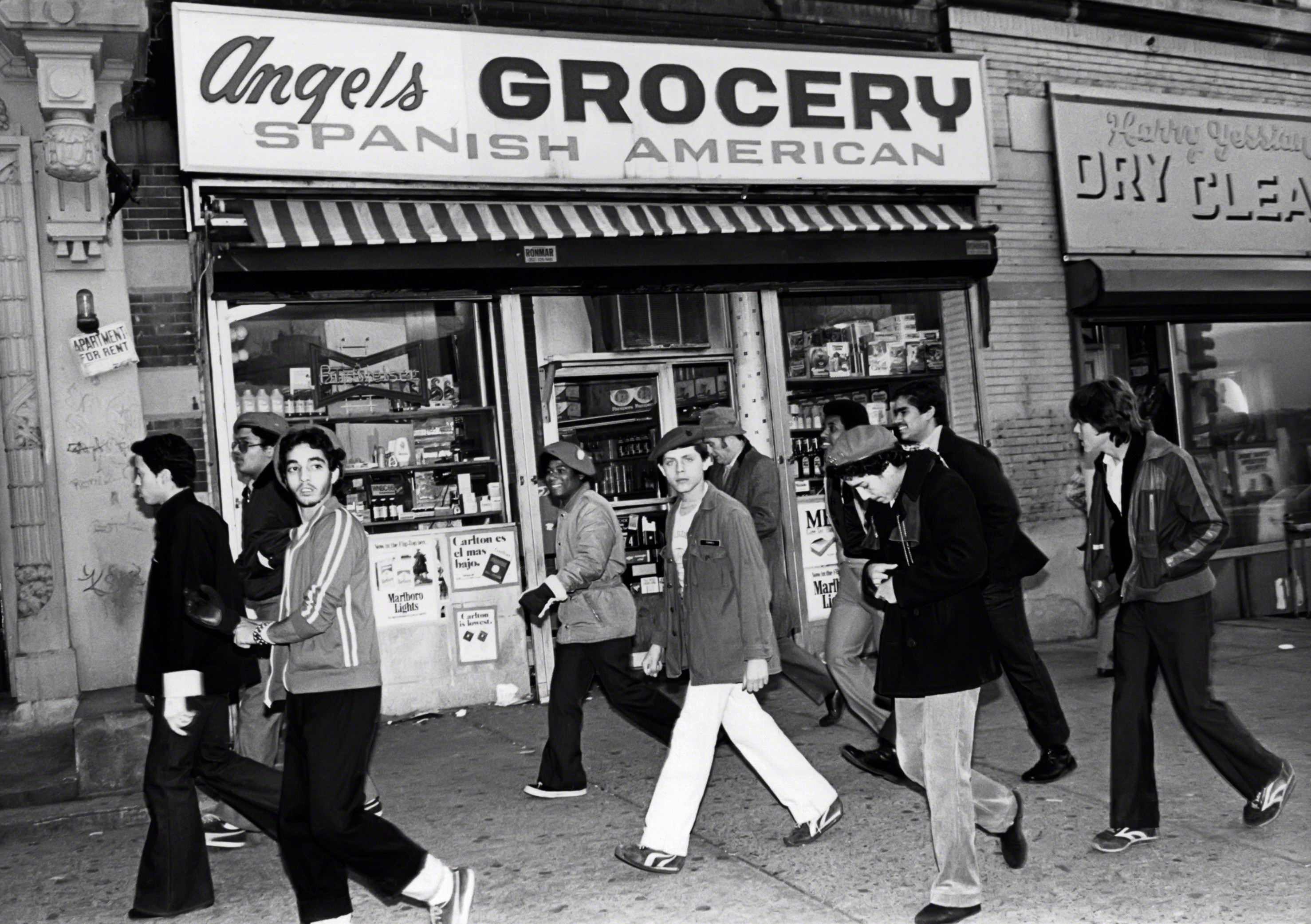

“Welcome to Fear City.” It was these words that greeted international tourists as they touched down in America’s concrete jungle in the month of June 1975. During an era when crime was at an all-time high, members of the New York City Police Department handed out what were dubbed “survival guides” to the growing island of Manhattan. From suggestions to “safeguard your handbag” and “conceal property in automobiles”, the pamphlet also advised to “Avoid public transportation.”

Hiding beneath the crowded pathways and towering buildings of the bustling metropolis is the dank and eerie New York City subway. Considered the pinnacle of innovation at its inception in 1904, the seemingly innocuous environment has instead welcomed in the misfits, criminals and societal outcasts into the hallowed mazes – the apt setting for Joaquin Phoenix’s new film, Joker. And just as the damaged character found refuge in the twisted darkness, so too have the world’s most notorious and unlikely criminals. The screeching of electrified tracks is reminiscent to the screams of its claimed victims, and the warm, musty smell of sweaty commuters, the homeless and an underlying rat epidemic reminds riders of the creature comforts that lie above ground. In 1981, Paul Theroux, an American travel writer and novelist, spent a week journeying through the notorious labyrinth of NYC’s subway system. Ruminating on his time through the graffiti-ridden, rat-infested tunnels, the accomplished author reported his findings in his book Subway Odyssey. During his journey, he was given one simple, yet profound rule for riding the subway: “Rule One is – don’t ride the subway if you don’t have to.”

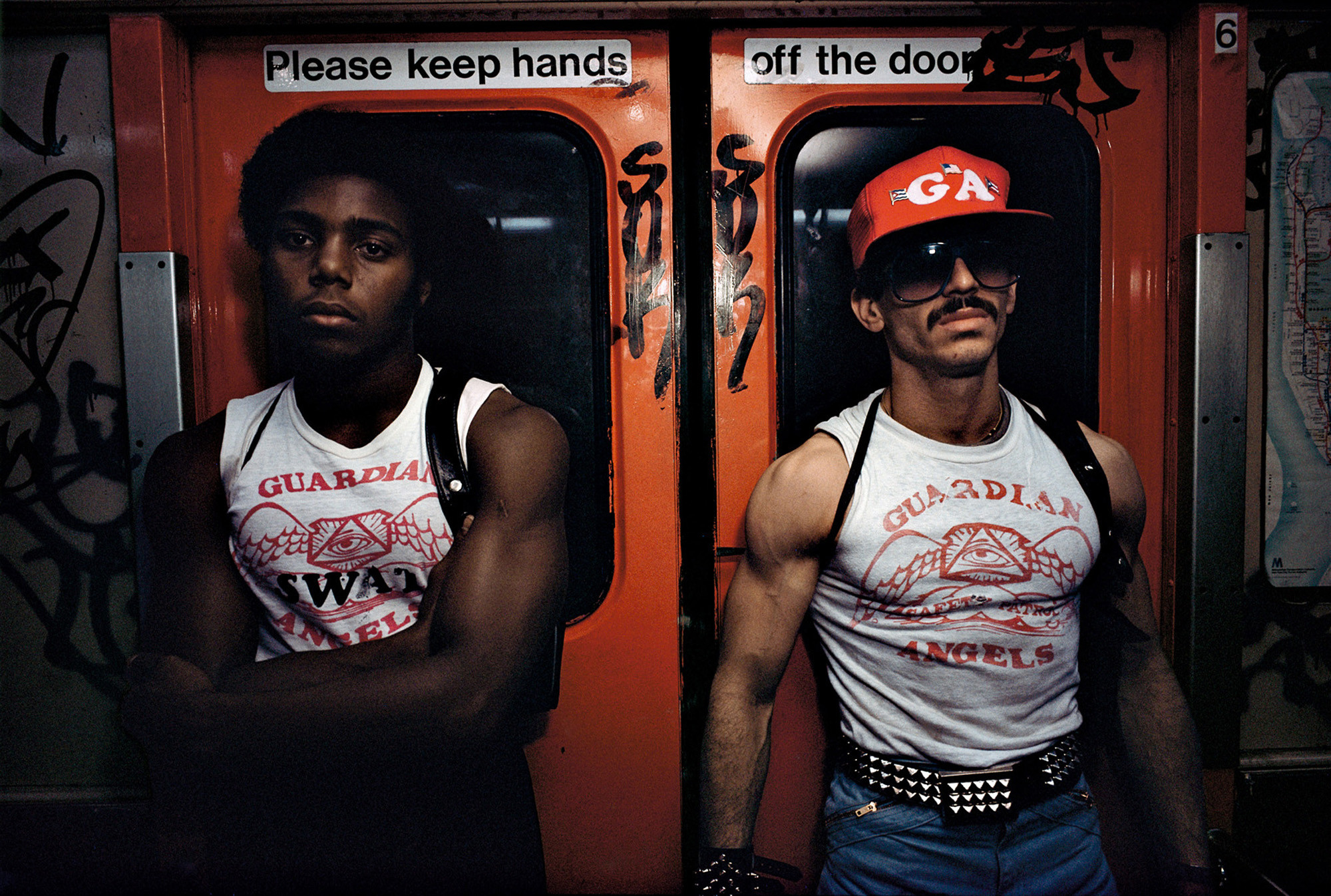

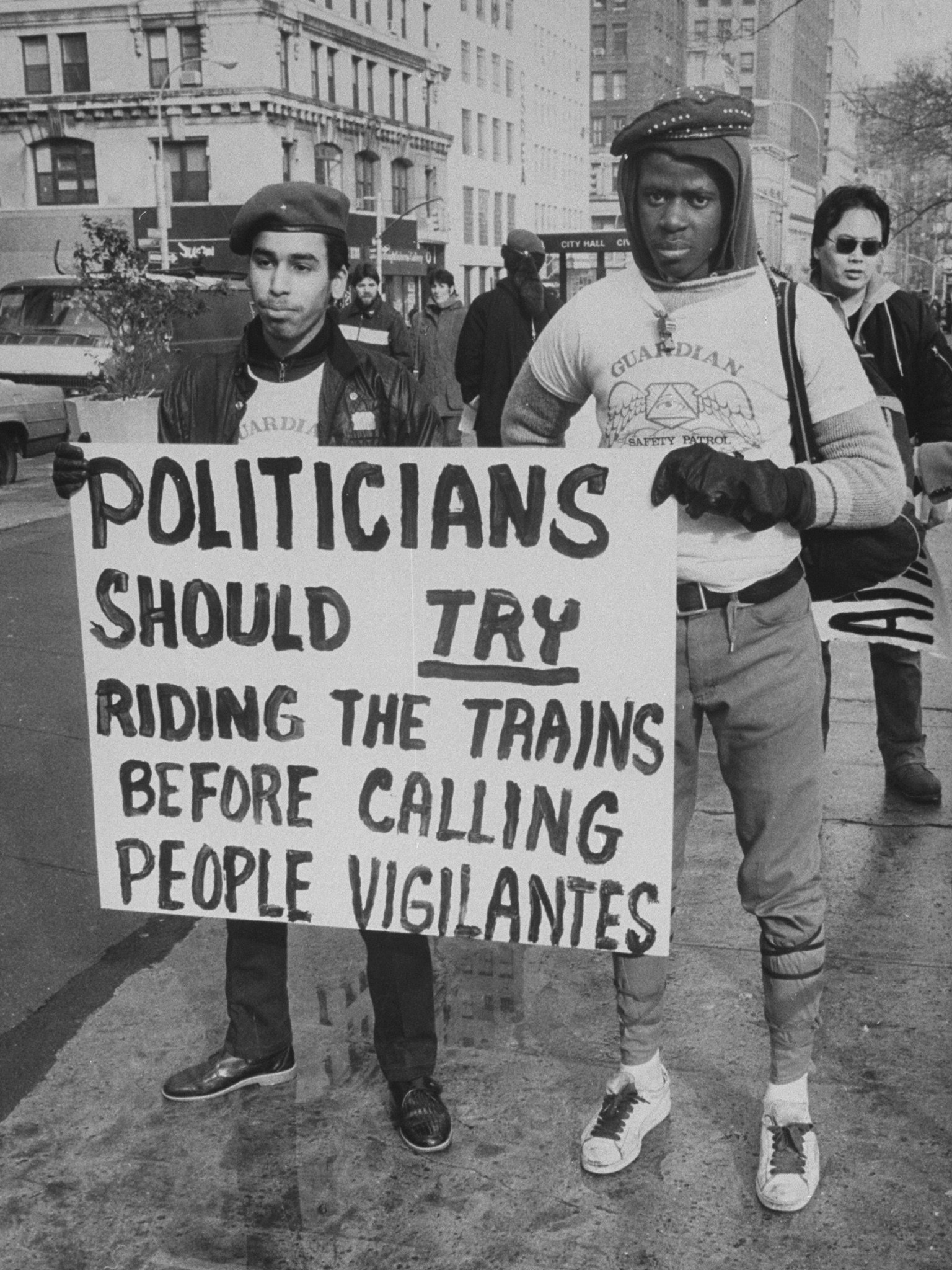

To use the subway was to risk your life, and the platform resembled a dystopic war zone with little law to protect its users. Today, more than five million people ride the NYC subway tracks each day, or 60 per cent of the population. While cases of crime make up a minute portion of its riders, fears are rising over an increase in crime rates. Long-problematic hate crimes, random attacks and dealings gone wrong are all contributing factors to the new rise of subway crime. “It’s a form of street collateral violence,” Guardian Angels founder Curtis Sliwa tells ICON. “In Brooklyn, the most dangerous stations are along the A train, C train ,L train and J train lines that run through Brownsville and East New York.”

While the tunnels hold a slew of tall tales and fictional horror stories in its humid alcoves – including mole people and alligator infestations – the reputation of the subway precedes itself with ill-famed cases and shocking acts of crime, some of which have never been solved. For when you ride the service, it is not the drunken passengers nor the homeless men looking for a place to rest that are to fear. No, it is the members of society whom appear as we do, but have a far darker intent than to simply ride the L train to Brooklyn.

Broad Channel

In 1979, at the height of transit crime in New York City, Mayor Ed Koch implemented a $7.5 million plan to combat the growing pandemic of felonies the system faced, and so 900 uniformed police officers went to urban war. Broad Channel, a neighbourhood within the New York City borough of Queens, is bordered by the calm waters of Jamaica Bay. Its station served as the hangout for a notorious teenage “station gang” during the late ’70s and the delinquents were known by the community.

On January 16, 1979, two women suffered fatal burns after three Broad Channel teenagers – two boys and a girl aged 16 to 18 – caused a deadly explosion in the local train station. The women, Regina Reicherter, 56, and Venezea Pendergast, 47, were on shift at 9.50pm behind the counters when the three juveniles pumped a flammable gasoline concoction into the coin slot of the glass ticket booth with a re extinguisher. The space caught alight and exploded with the two women inside. As a result, Reicherter suffered burns to 65 per cent of her body while her colleague was in a serious condition with burns to 20 per cent of her body. Both died. The heinous crime was reportedly a revenge plot after one of the perpetrators, Wilham Prout, received a summons the day before for jumping a turnstile.

Three days later, on January 19, the teenager and one of his fellow offenders, Linda Krauss, were arrested and appeared in Queens Criminal Court on charges of arson, assault and attempted murder – neither had any prior convictions. The third suspect, Peter Grassia, 16, was held without bail and faced the same charges several days later. On March 21, it was reported by The New York Times that the three teenagers were awaiting charges for second-degree murder following the deaths of the two clerks. The last known movements placed Krauss in jail on the island of Rikers in the East River while the two boys were moved to an unknown facility to protect the teenagers from other inmates. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the tragic crime that will forever plague the population of Broad Channel.

Nostrand Avenue

The biggest fear for authorities when investigating a murder is the potential of a cold case; not being able to convict a killer who remains at large and walks among the innocent. For Rashawn Brazell, a gay African-American teenager, his family may never find peace as his murder in 2005 continues to be questioned.

On Valentine’s Day, February 14, 2005, the 19-year-old answered the front door of his Bushwick apartment and left with an unidentified male. The pair were seen entering the subway at Gates Avenue station and exited the Nostrand Avenue station in Bedford-Stuyvesant – the last known movements of the teenager. He reportedly had plans to see his mother that afternoon but never showed.

The motive behind Brazell’s murder is unclear, but according to Sliwa, who has been patrolling the New York City subways since 1979, he says that, despite common misconceptions, hate crime is uncommon. “Do victims know their perpetrators? Generally, yes,” he says. “If not directly, normally word in the street gets around and then [the victim] knows for sure. Hate crimes in the streets are rare, racist words might be said… but that is not the primary motivation.”

Four days later, Brazell’s right shoulder, right arm and lower legs were found by a transit worker in a blue garbage bag on the A line between Nostrand Avenue and Franklin Avenue station. On February 23, his pelvis and torso were discovered at a recycling plant in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, roughly eight kilometres from where he was last seen. To this day, his head has never been uncovered. His limbs were said to have been dismembered with medical precision and the unknown perpetrator had intimate knowledge of the Brooklyn subway system.

“To this day, his head has never been uncovered. His limbs were said to have been dismembered with medical precision and the unknown perpetrator had intimate knowledge of the Brooklyn subway system.”

The case never resulted in an arrest until it was reopened by the cold case unit at NYPD and the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office in 2016. At the time, the main suspect of his murder, Kwauhuru Govan, a resident of the same neighbourhood where Brazell lived, was on trial for the similarly horriffic murder of 17-year-old girl Sharabia Thomas. On February 11, 2004, in a Bushwick alley, Thomas’s naked and battered body was found stuffed into two laundry bags. Govan’s DNA matched the DNA found under the victim’s nails and he has since been convicted of Thomas’s murder in the second degree and faces imprisonment of 25 years to life. In relation to the 2005 murder, Govan had lived across the street from Brazell and the evidence against him – though not publicly disclosed – is said to be strong. While serving time in prison, it was last reported that Govan had appealed to the court for an anonymous trial, as the defendant believed the jury would not believe him if his identity was to be uncovered. In June 2019, his appeal was denied. The trial is still ongoing.

East Broadway

In an era where almost everything is captured on social media, even the most bizarre of circumstances can garner worldwide attention. But following a violent altercation between a group of men and a uniformed police officer, the military-trained official has been sung as a hero after de-escalating a potentially fatal situation.

On Sunday evening, December 23, 2018, five homeless men entered into an abusive fight on the F platform of the East Broadway subway station. Reportedly told minutes earlier to move on after harassing a young woman on the platform, the five men turned on NYPD o ffier Syed Ali. Armed with just his two feet and a baton, the cop, who had military experience in Iran and Afghanistan, single-handedly diffused the situation. “Crime on the subway is rising in two categories – and both target women,” Sliwa says. “They are sexual assault and sexual harassment.”

A video from a bystander that captured the entire incident was posted to Twitter and immediately went viral. The post had shown a man who had been kicked to the ground standing up before throwing punches while the other four men, who were said to be highly intoxicated, continued to approach officer Ali. One onlooker entered the situation to try to distance the men from the police officer, but one of the assailants broke through the barrier to storm Ali. The perpetrator was kicked, lost his footing and fell onto the track below. “Lots of people who are not involved get injured when they are in proximity to where the street violence is taking place,” explains Sliwa. But, unlike this incident, the volunteer patroller believes homeless people are more often the “target of attacks”. “It makes headlines when an emotionally disturbed person attacks a member of the general population.” Officer Ali recalled to journalists that he called for the electricity to be cut off from the deadly “third” track, to save the man’s life. No one was seriously injured but the men involved were taken to hospital for evaluation. The perpetrators were not immediately charged until they were found in the same subway station the next day. Three of the men, Eliseo Alvarez, 36, Leobardo Alvarado, 31, and Juan Nunez, 27, were arrested and charged with riot and obstructing governmental administration, the NYPD said.

Penn Station

Not all crimes involve blood being drawn, but rather those simply fascinated with the public transport system who literally take matters into their own hands – at least that is the case for 54-year-old Darius McCollum. Currently serving time in Mid-Hudson Forensic Psychiatric Center for more than 30 incidents of train and bus ‘hijacking’, his name has quickly become infamous in the city of New York. The latest case in his slew of offences placed McCollum in Manhattan for stealing a Greyhound bus in 2015, but the man who suffers from Asperger’s Syndrome started his illegal spree at just 15 years old in 1980.

After impersonating a Metropolitan Transportation Authority transit worker, McCollum arrived at the beginning of a shift to drive an in-service New York City subway E train. After spending much of his childhood at the MTA railyard, the teenager had a strong grasp on the inner workings of the machinery required to operate the train. Reportedly covering an MTA employee’s shift so that the worker could visit his girlfriend, McCollum transported a passenger train around the peak-hour route from 34th Street to Penn Station to the World Trade Center. With no intention to harm its riders or transit workers, McCollum successfully completed the popular route until a passenger noticed the young man alone in the operator’s cabin. The train was stopped and McCollum was arrested. He was soon dubbed the “subway bandit” by New Yorkers.

Since then, the transit impostor has been involved in a number of incidents that includes driving a bus from a Harlem depot to Queens Village, stealing a subway repair truck, and in 2010, taking a Trailways bus from a depot in Hoboken – he was caught on the way to JFK airport. Following the events of 911, McCollum volunteered his time and knowledge to the MTA in a bid to make the city subways safer. Still incarcerated, he led a team from New York City Intelligence Detectives and New York State Police in shackles through the layered subway system to identify locations where intruders may be able to enter without being detected. His contributions resulted in the Department of Corrections to believe the man was easily manipulated and could prove a valuable asset to terrorist organisations. He was later placed in solitary confinement. At this time, an appeal has been made for his release from prison.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE OCTOBER 2019 EDITION OF ICON AUSTRALIA.

RECEIVE YOUR ISSUE HERE.