Everything

To French Philosopher Baudrillard, much of modern art is based on disappearance, in particular, the disappearance of meaning; as the acknowledgement of the “nothing” is essential for the virtue of modern art. Whilst many critics argued that the threat of mercantile value would reduce the work of art to the status of a mere object, Baudrillard argues that art will eventually demean itself to the state of “art for art’s sake”. If this is true, why does Jacob Vilató paint?

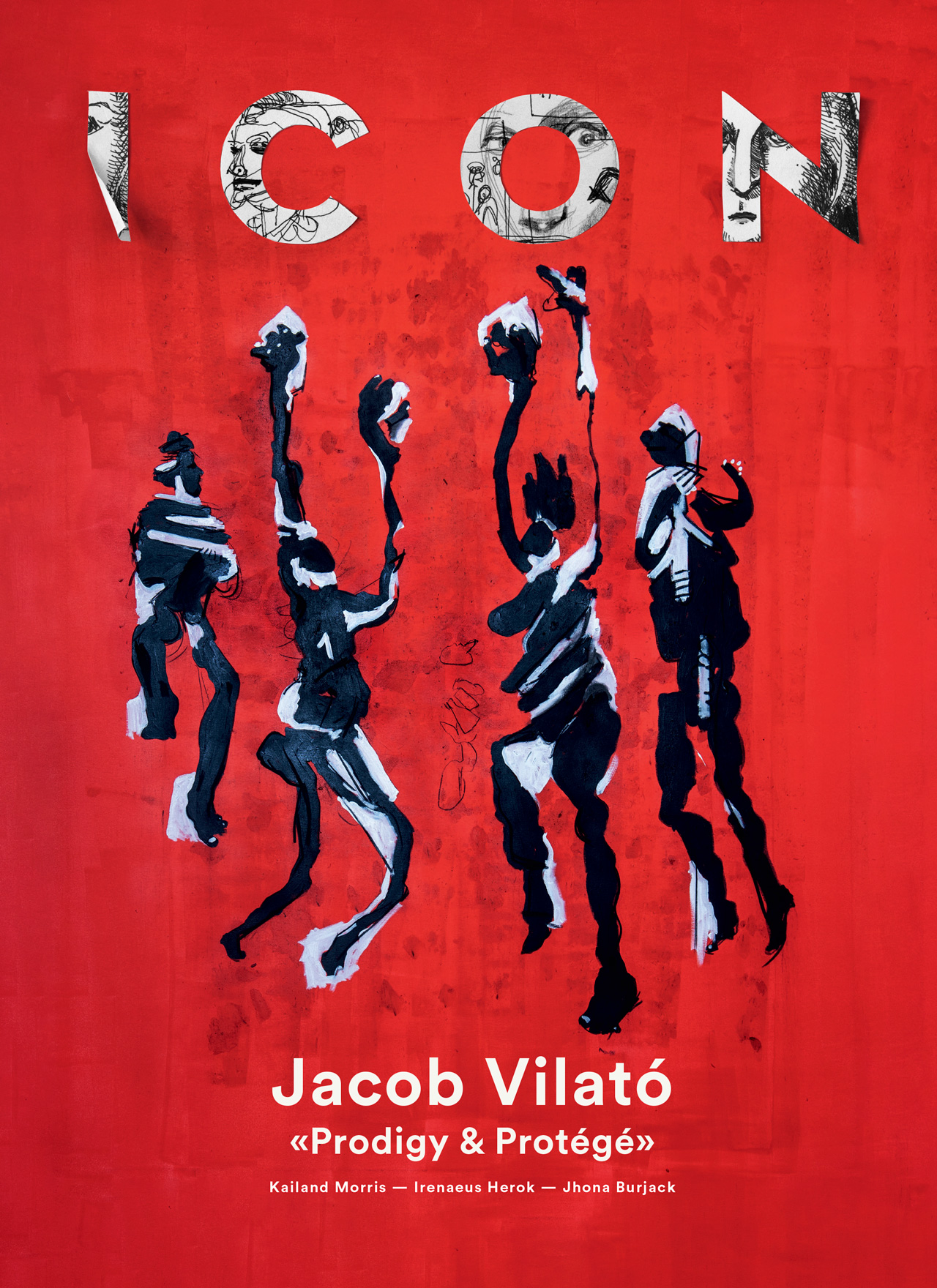

“I honestly don’t know yet. Ask me in 20 years. Maybe then I’ll have an answer,” responds Vilató over a Zoom call between preparations for an exhibition in Mexico and painting the ICON cover. “I tend to focus a lot on what I do. So, I forget about friends. I forget about happy stuff”.

Vilató’s disappearance into workmode is what defines his art. “Placing my work somewhere, or pondering why people would like it, or asking what it adds to the world is not really my process. I’m rather iconoclast. I don’t see myself as some God of painting – rather quite the opposite. When I see people are buying my paintings I ask myself ‘what will happen with those paintings once I’m dead?’ For me, it’s very hard to place the existence of my works on a timescale. I never know if I belong to a generation or not, I don’t see myself in a group. Because I try not to copy or follow trends. So that somehow takes you out of time.” I jump right in.

Marne Schwartz (ICON): Does your practise go in phases? Or do you investigate something until it’s finished? How do you approach this aspect of work between the disciplines of art and design?

Jacob Vilató (Vilató): Well, I started with architecture. I had a firm for about 15 years, practising mainly in China and India. Then, I decided I needed a change, and now I mainly paint. Designing and painting, for me, both are very natural. There’s a slider bar between the two, and I move it up and down depending on the requirements. But I would say I tend to work in phases. I’m always painting; I might spend one month painting and then I’ll spend two weeks preparing some designs, and vice versa. But it’s never at the same time. I paint every day; I don’t design everyday.

ICON: Do you think that objects offer a closer connection between the artist and the audience than your art does?

Vilató: I’m not sure. I think a lot of people who buy art just do it because it looks good, or because it matches their wall or whatever. Not everyone who buys paintings love the painting itself. They don’t see through it, they don’t go deeper. But with an object, the nice thing is that people can touch it, and it really goes beyond a wall. They leave with that. So maybe it’s like a closer relation. And that’s what I really like about objects. The Switcher is essentially a spoon that we designed for social settings. For example you can eat caviar with your friends. And because of its shape it remains clean. And when you’re done with the caviar, you can flip it, and then you can have a shot of vodka in the hollowed glass below.

So this makes the object part of your life, you interact with it. And I really like that – you can love an object easily. You can love your chair, or your sofa. And it’s there every day of your life, or at least for maybe, I don’t know, one year, five years, et cetera. So it’s like a box for memories. And I think it happens more and more, that an object helps define who you are. So this gets closer to people. And at the end, I want to communicate with people. I want to talk to them, to become part of their lives in some respect. That’s what’s exciting. When they collect something of mine and get an emotional reaction from it, this makes me happy. The person feels like it’s their thing. They feel somehow the object is part of them or they communicate themselves via the object.

ICON: What objects have communicated to you, and how do you listen?

Vilató: I think that the nice thing about many objects is the interaction starts when you’re a child. Take a chair. You live all your youth life with that object. You don’t think that much about it, it’s just there, and you interact with it, and it’s there. Then you leave your home because you’re, I don’t know, 18. And then you see this chair, 20 years later, and it brings a myriad of feelings. And you can even smell what your house used to smell like, feel emotions you had when in the same room as the chair. Playing with those feelings is what’s exciting. I don’t really understand my childhood memories – why certain elements remain and some others do not. It becomes some kind of exploration for me.

ICON: How do you reimagine these narratives which have already told their story in your life? In your work are you simply documenting them according to your memories? Or are you creating a new narrative inspired by these objects?

Vilató: I think there are two different experiences I have. The first is leaving objects completely as they are, not trying to discover anything, just having them around, you touch it, et cetera, having the same experience that you used to have. And then the other way is I try different approaches to that object. Like, I don’t know, there was a stool in my house, which was the head of a bull with three legs. Then one way to understand it, is just to design it again, but with your new ideas. Or you just try to paint it and see what comes out of it. And sometimes when you paint something, you see a different aspect. Because there are some gestures that are automatic. When you see something, you just see, you don’t really understand.

When you start drawing it, maybe you go first for the point of the nose or the chin, and this shape tells you something. Or you put a lot of light in one spatial area, or you see a jaw manifesting that you’re drawing that does not match exactly the one in front of you. It’s very hard to explain.

ICON: How do you determine which approach to take? Do you attempt one experience, and then redo it if you’re not happy?

Vilató: I think when you redo something, even when you have no intention prior to that, something comes out of it. You do it once, and then you do it twice, and it’s a little bit different. There’s something that keeps exaggerating. And then when you do that a lot of times, then you are in a totally different position. It’s like you have distilled the essence of the subject, but with many different representations. I don’t know how that process works, but it works. So that’s maybe my approach.

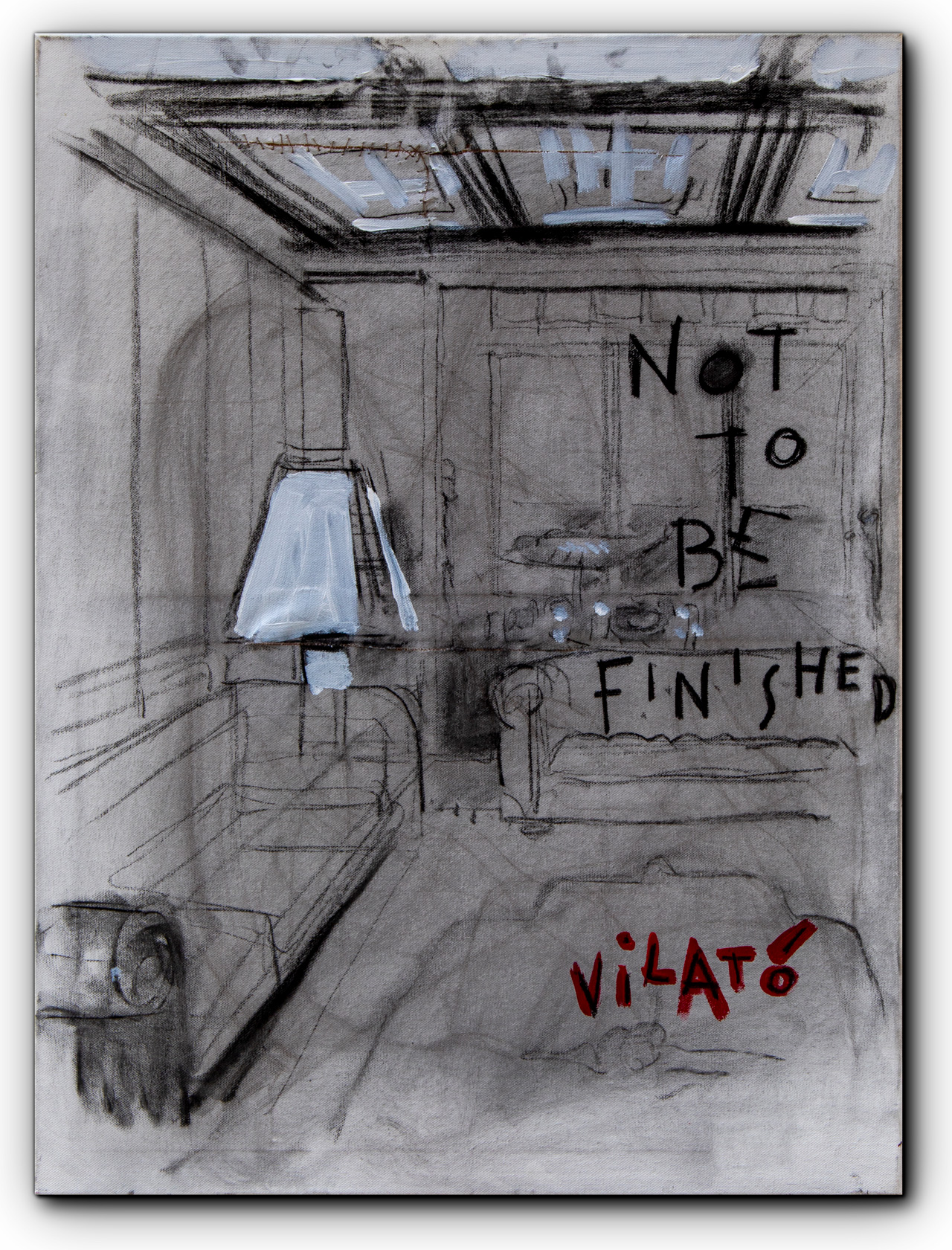

ICON: Which of the iterative works becomes “The Work”? How do you even choose?

Vilató: That’s the dangerous thing for me, it’s when you start with something and you go through the same thing over and over again. I obsess over things. It is a big difference between copying an object for the sake of it, and evolving it. Many painters do the same thing over and over again. There’s this struggle for me, identifying the difference between creating something automatic in a bad way, and freeflowing to create a natural evolution of something I have become obsessed with.

ICON: How do your own obsessions drive your inspiration?

Vilató: There’s no place for anything else. I don’t know why, I think maybe my brain works in a different way. I think it’s because I can’t think of anything else besides my obsessions. It seems strange, but it’s very natural to me. It’s just the way it goes. I start thinking about something and it builds, it doesn’t change. My obsessions grow to a bigger network and become linked to everything else. I can see a link in everything. It’s like when you’re in love, and you go walking by the street and you can smell them, or see a scarf they wear and immediately think it’s them, but it’s not. So I think it’s somehow the same.

ICON: How confident are you in translating your obsessions into your art?

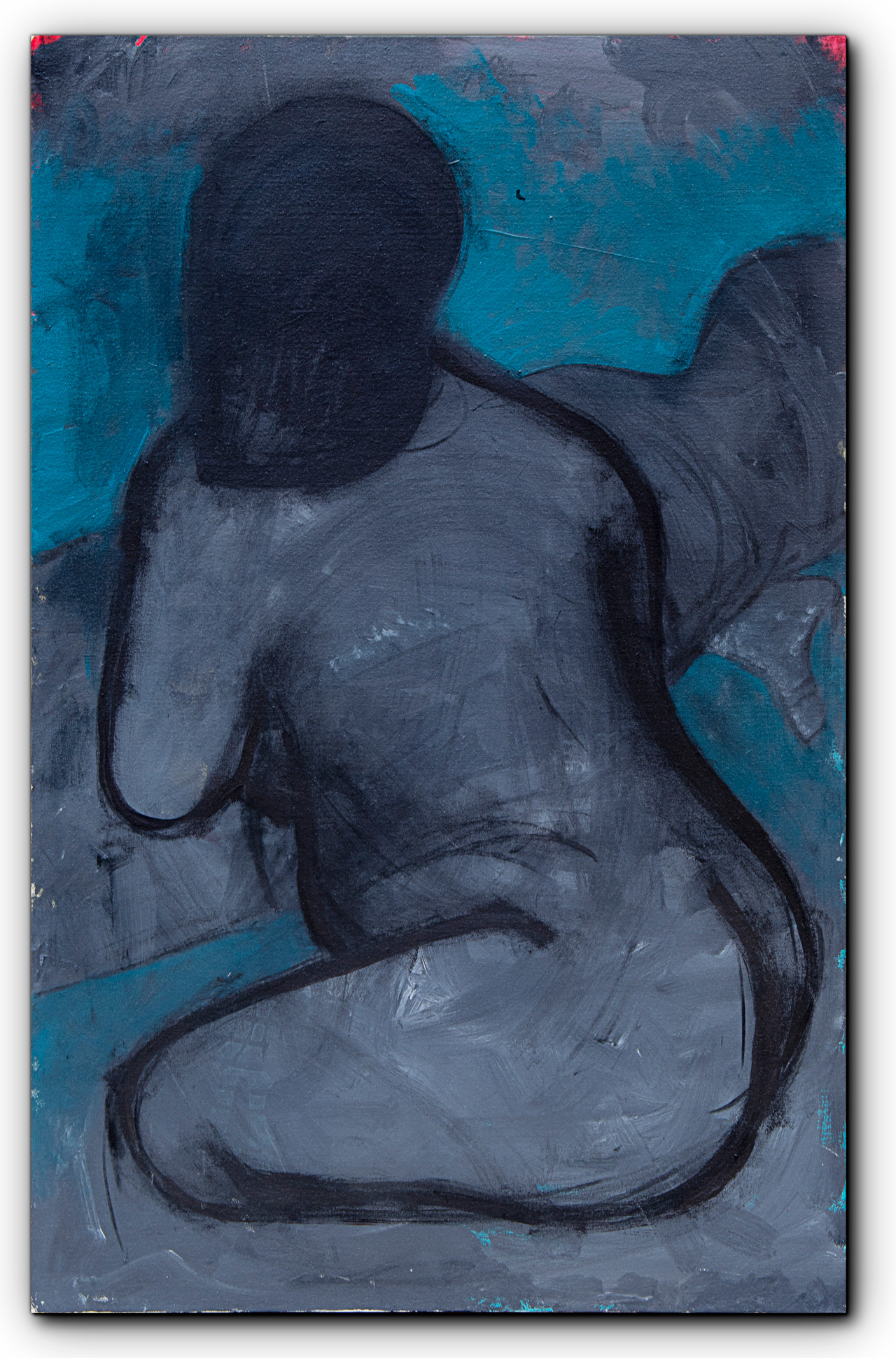

Vilató: When you’re painting, it’s like somehow getting naked, and you’re showing something you wouldn’t dare. I don’t know, if you paint something super erotic, you don’t want to show that to your mother or your friends. So you just paint it, and you leave it there. It’s one thing painting obsessions, it’s another entirely talking about obsessions. It feels too intimate for me to be explicit in this regard.

ICON: Sometimes the obsession is the obsession itself?

Vilató: For me, yes. I struggle with this deeply. On the other hand it becomes my work, so I suppose it’s not all that bad.

ICON: How do you know when your work or your focus on a topic or obsession is finished? How does it naturally finish?

Vilató: Like my job here is done? I don’t think the obsessions really leave and are gone. I was obsessed with the Beatles when I was, I don’t know, 18 years old. But then the Beatles led me to other kinds of obsessions like photography, like old cars. And from old cars, I jumped to another area of design. So it’s like little branches of the same tree. I just start with one thing, and then explode. And then those branches have multiple pathways that connect back between themselves again. I don’t think I ever abandon the obsessions, I just keep adding layers.

ICON: Pictures of pictures. Layers atop layers. How are you not lost in this labyrinth of contemplation?

Vilató: That’s the thing… I’m not actually afraid of copying an object, I’m far more afraid of copying myself. I don’t want to become a caricature of myself and lose the creator. There are painters who do the same thing day in and out. I don’t want to get to 80 years of age and have been doing the same thing since I was 40. The versions of my obsessions I paint are not necessarily getting better. It’s me giving a different life and story to them so they can become something else entirely.

Somehow I didn’t have to wait 20 years for Vilató to answer the question on why he paints.

Art: Jacob Vilató

Words: Marne Schwartz